The Human Being as a Physical and Spiritual Entity

GA 205

15 July 1921, Dornach

Translated by Steiner Online Library

Eleventh Lecture

Today I will summarize some truths that will serve us in turn to provide further explanations in a certain direction in the coming days. If we consider our soul life, we can say that towards one pole of this soul life lies the element of thinking, towards the other pole the element of will, and between the two the element of feeling, that which in ordinary life we call feeling, the content of the mind, and so on. In the actual life of the soul, as it takes place in us in our waking state, there is never just one-sided thinking or will, but they are always in connection with each other, they play into each other. Let us assume that we behave very calmly in life, so that we can say, for example, that our will is not active externally. However, when we think during such outwardly directed calmness, we must be aware that will is at work in the thoughts we unfold: in connecting one thought with another, will is at work in this thinking. So even when we are seemingly merely contemplative, merely thinking, at least inwardly the will is present in us, and unless we are raving or sleepwalking, we cannot be willfully active without letting our volitional impulses flow through thoughts. Thoughts always permeate our volition, so that we can say: the will is never present in the life of the soul in isolation. But what is not present in this isolated way can still have different origins. And so the one pole of our soul life, thinking, has a completely different origin than the life of the will.

Even if we only consider everyday life, we will find that thinking always refers to something that is there, that has prerequisites. Thinking is mostly a reflection. Even when we think ahead, when we plan something that we then carry out through the will, such thinking is based on experience, which we then act upon. In a certain respect, this thinking is, of course, also a reflection. The will cannot be directed towards what is already there. In that case, it would always be too late. The will can only be directed towards what is to come, towards the future. In short, if you reflect a little on the inner life of thought, of thinking and of the will, you will find that even in ordinary life, thinking relates more to the past, while the will relates to the future. The inner life of feeling stands between the two. We accompany our thoughts with feeling. Thoughts please us, repel us. Out of our feeling we lead our impulses of will into life. Feeling, the content of the mind, stands between thinking and willing, right in the middle.

But just as it is the case in ordinary life, even if only in a suggestive way, so it is in the great world. And there we have to say: what constitutes our thinking power, what makes up the fact that we can think, that the possibility of thought is in us, we owe it to the life before our birth, or rather before our conception. In the little child that comes to meet us, all the thinking abilities that a person develops are already present in the germ. The child uses thoughts only - as you know from lectures I have already given - as directing forces to build up its body. Especially in the first seven years of life, until the change of teeth, the child uses the powers of thought to build up its body as directing forces. Then they emerge more and more as actual thought forces. But they are thoroughly predisposed in the human being as thought forces when he enters physical, earthly life.

What develops as will forces - an unbiased observation readily reveals this - is actually connected with this thought force only to a small extent in the child. Just observe a wriggling, moving child in the first weeks of life, and you will already realize that this wriggling, this chaotic movement, has only been acquired by the child because his soul and spirit have been clothed with physical corporeality by the physical external world. In this physical body, which we only develop little by little from conception and birth, the will initially lies, and the development of a child's life consists in the fact that gradually the will is, so to speak, captured by the powers of thought that we already bring with us into physical existence through birth. Just observe how the child at first moves its limbs quite senselessly, as it comes out of the activity of the physical body, and how gradually, I might say, thought intrudes into these movements, so that they become meaningful. So there is a pressing and thrusting of thinking into the life of the will, which lives entirely within the shell that surrounds the human being when he is born, or rather, conceived. This life of the will is contained entirely within it.

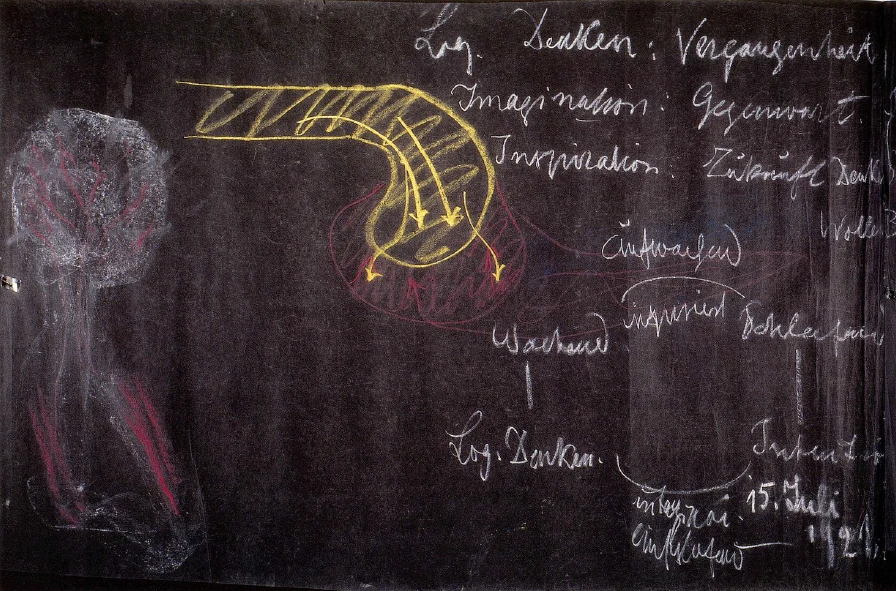

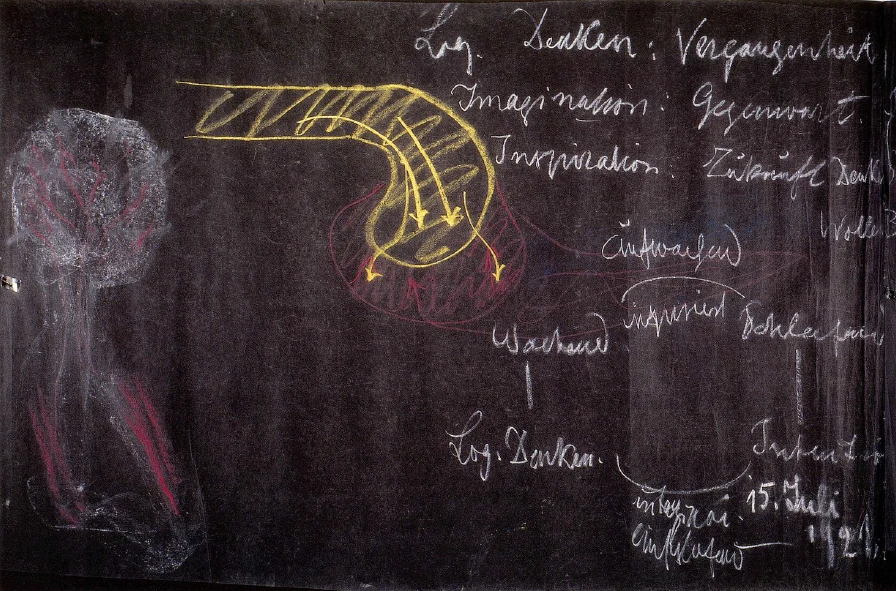

So that we can draw a schematic picture of a human being, in which we say that he brings his life of thought with him when he descends from the spiritual world. I will indicate this schematically (see drawing, yellow). And he begins his life of will in the physical body that is given to him by his parents (red). The forces of will are within, expressing themselves in a chaotic manner. And within are the powers of thought (arrows), which initially serve as directing forces to spiritualize the will in its corporeality in the right way.

We then perceive these forces of will when we pass through death into the spiritual world. But there they are highly organized. We carry them through the gate of death into spiritual life. The powers of thought that we bring with us from the supersensible life into earthly life, we actually lose in the course of earthly life.

With human beings who die young, it is somewhat different. For now, let us speak first of normal human beings. A normal human being who lives past the age of fifty has basically already lost the real powers of thought that were brought along from the previous life and has just retained the directional powers of the will, which are then carried over through death into the life that we enter when we go through the gate of death.

One can assume that someone is now thinking: Yes, so if you are over fifty years old, you have lost your thinking! - In a sense, this is even the case for most people who are not interested in anything spiritual today. I would just like you to really endeavor to register how much original, inventive thought power is produced by those people today who have reached the age of fifty! As a rule, it is the thoughts of earlier years that have automatically moved on and left an impression on the body, and the body then moves on automatically. After all, the body is a reflection of our mental life, and the person continues in the old rut of thought according to the law of inertia. Today, the only way to protect oneself from continuing in the old rut of thought is to absorb thoughts during one's lifetime that are of a spiritual nature, that are similar to the thought-forces in which we were placed before our birth. So that indeed the time is approaching when old people will be mere automatons if they do not take care to absorb thought-forces from the supersensible world. Of course, man can continue to think automatically; it may appear as if he is thinking. But it is only an automatic movement of the organs in which thoughts have been laid, have been woven in, if the human being is not grasped by that youthful element that comes when we absorb thoughts from spiritual science. This absorption of thoughts from spiritual science is certainly not just any kind of theorizing, but it intervenes quite deeply in human life.

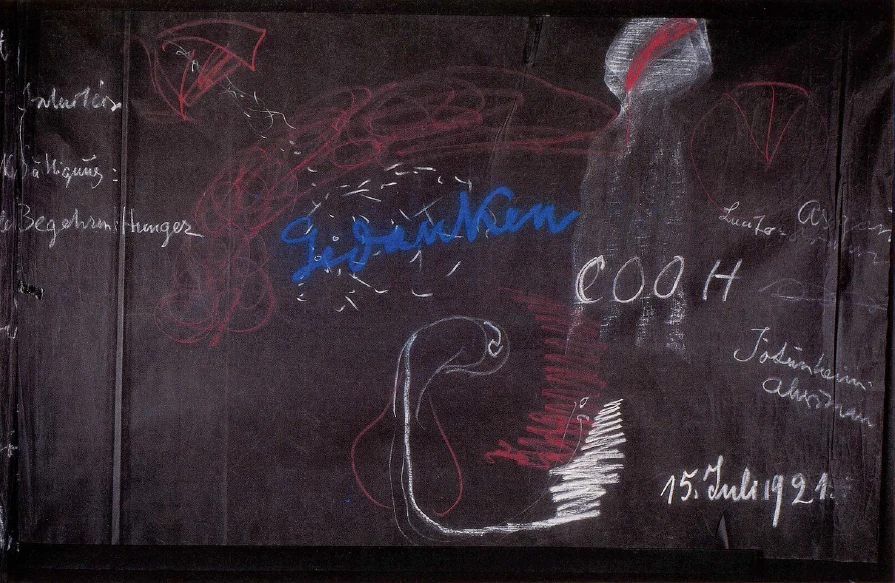

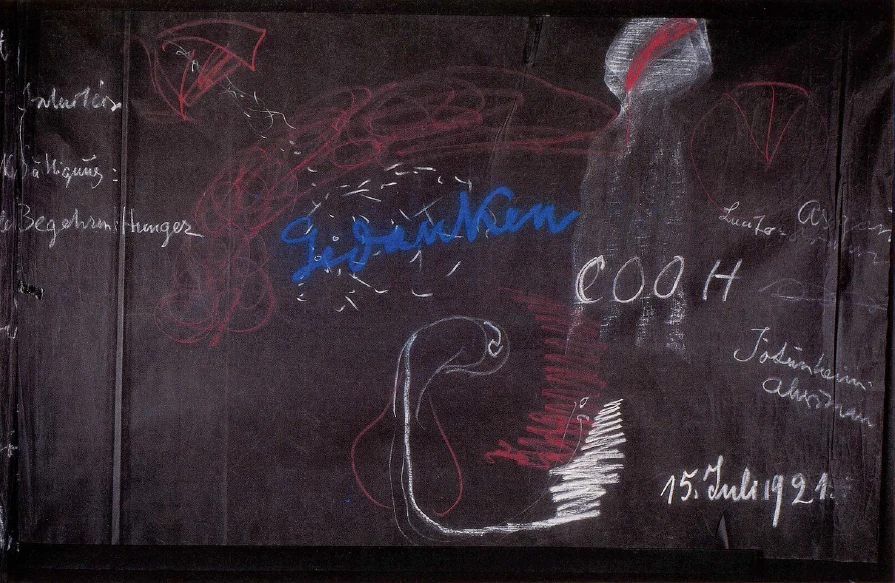

But the matter takes on particular significance when we now consider man's relationship to the surrounding nature. I now understand by nature all that surrounds us for our senses, to which we are thus exposed from waking up to falling asleep. This can be considered in a certain way in the following way. One can visualize what one sees — I mean before spiritual eyes. We call it the sensory carpet. I will draw it schematically. Behind everything that one sees, hears, perceives as warmth, the colors in nature and so on – I draw an eye as a schema for what is perceived there – there is something behind this sensory carpet. Physicists or people of the present world view say: Behind it are atoms and they swirl -, and afterwards, right, as they continue to swirl, there is no sensory carpet at all, but somehow in the eye or in the brain or somewhere or not somewhere, they then evoke the colors and the sounds and so on. Now, please, imagine, quite impartially, that you begin to think about this sensory carpet. If you start thinking and do not assume the illusion that you can observe this huge army of atoms, which the chemists have arranged in such a military way of thinking, let us say, for example, there is Corporal C, then two privates, C, O, O, and then another private as an H; isn't that right, that's how we arranged it militarily: aether, atoms and so on. Now, if, as I said, you do not succumb to this illusion but remain with reality, then you know: the sensory carpet is spread out, the sensory qualities are out there, and what I still grasp with consciousness about what lies in the sensory qualities is just thoughts. In reality, there is nothing behind this sensory carpet but thoughts (blue). I mean, behind what we have in the physical world, there is nothing but thoughts. We will talk about the fact that these are carried by beings. But you can only get behind what we have in our consciousness with thoughts. But the power to think we have from our prenatal life or from the life before our conception. Why is it then that we can penetrate behind the sensory curtain by means of this power?

Just try to familiarize yourself with the idea that I have just mentioned, and try to properly present the question to yourself on the basis of what we have just hinted at, which we have already considered in many contexts. Why is it that we can reach below the sensory level with our thoughts, when our thoughts come from our prenatal life? Very simply, because behind it is that which is not in the present at all, but which is in the past, which belongs to the past. That which is under the carpet of sense is indeed a past, and we only see it correctly when we recognize it as a past. The past has an effect on our present, and out of the past sprouts that which appears to us in the present. Imagine a meadow full of flowers. You see the grass as a green blanket, you see the meadow's floral decoration. That is the present, but it grows out of the past. And if you think through this, then underneath it you do not have an atomistic present, but in reality you have the past as related to what comes from you yourself from the past.

It is interesting: when we begin to reflect on things, it is not the present that is revealed to us, but the past. What is the present? The present has no logical structure at all. The sunbeam falls on some plant, it shines there; in the next moment, when the direction of the sunbeam is different, it shines in a different direction. The image changes every moment. The present is such that we cannot grasp it with mathematics, not with the mere structure of thought. What we can grasp with the mere structure of thought is the past, which continues in the present.

This is something that can reveal itself to man as a great, as a significant truth: When you think, you basically only think the past; when you spin logic, you basically reflect on what has passed. - Anyone who grasps this thought will no longer seek miracles in the past either. For in that the past is woven into the present, it must be in the present as it is in the past. If you think about it, if you ate cherries yesterday, that is a past action; you cannot undo it because it is a past action. But if the cherries had the habit of making a mark somewhere before they disappeared into your mouth, that mark would remain. You could not change this sign. If every cherry had registered its past in your mouth after you had eaten cherries yesterday, and someone came and wanted to cross out five, he could cross them out, but the fact would not change. Nor can you perform any miracle with regard to all natural phenomena, because they are all intrusions from the past. And everything we can grasp with natural laws has already passed, is no longer present. You cannot grasp the present other than through images; that is a fluctuating thing. When a body lights up here, a shadow is created. You have to let the shadow properly define itself, so to speak, and so on. You can construct the shadow. That the shadow really comes into being can only be determined by devotion to the picture. So that one can say: even in ordinary life, limitation, I could also say logical thinking, refers to the past. And the imagination refers to the present. In relation to the present, man always has imaginations.

Just think, if you wanted to live logically in the present! No, to live logically means to draw one concept from another, to move from one concept to another in a lawful manner. Now, just imagine yourself in life. You see some event: is the next one logically connected to it? Can you logically deduce the next event from the previous one? When you look at life, are not its images similar to a dream? The present is similar to a dream, and only that the past is mixed into the present, which causes the present to proceed in a lawful, logical manner. And if you want to divine something in the future in the present, yes, if you just want to think of something you want to do in the future, then that has happened in a completely non-representational way in the first instance. What you will experience tonight is not in your mind as an image, but as something more non-pictorial than an image. At most, it is in your mind as inspiration. Inspiration relates to the future. Logical thinking: past Imagination: present Intuition Inspiration: future.

| Logical thinking: | Past | Intuition |

| Imagination: | Present | |

| Inspiration: | Future |

We can also use a simple diagram to visualize what is involved. When a person – let me characterize him here by this eye (see drawing on page 198) – looks at the tapestry of the senses, he sees it in its transforming images, but he now comes and introduces laws into these images. He develops a natural science out of the changing images of the sensory world. He develops a specialized science. But think about how this natural science is developed. You investigate, you investigate while thinking. You cannot possibly, if you want to develop a science about what spreads out as a carpet of senses, a science that proceeds in logical thoughts, you cannot possibly gain these logical thoughts from the external world. If what is recognized as thoughts and laws of nature were to follow from the external world itself, then it would not be necessary for us to learn anything about the external world. Then the person who, for example, looks at this light would have to know the exact electrical laws and so on, like the other person who has learned it! Equally, if he has not learned it, man knows nothing at all, let us say, about the relationship of an arc to the radius and so on. We bring forth from our inner being the thoughts that we carry into the outer world.

Yes, it is so: what we carry into the outer world as thoughts, we bring forth from our inner being. We are first of all this human being, who is constructed as a head human being. This human being looks at the carpet of senses. Inside the carpet of senses is what we reach through thoughts (see drawing page 198, white) and between this and between what we have inside us, what we do not perceive, there is a connection, so to speak an underground connection. Therefore, what we do not perceive in the external world because it extends into us, we bring out of our inner being in the form of thought life and place it in the external world. This is how it is with counting. The external world does not present anything to us; the laws of counting lie within our own inner being. But that this is true arises from the fact that between these predispositions, which are there in the external world, and our own earthly laws, there is an underground connection, a sub-physical connection, and so we draw the number out of our inner being. It then fits with what is outside. But the path is not through our eyes, not through our senses, but through our organism. And that which we develop as human beings, we develop as whole human beings. It is not true that we grasp some law of nature through the senses; we grasp it as a whole human being.

These things must be considered if we want to properly bring to mind the relationship between man and the environment. We are constantly in imaginations, and one need only compare life with dreams without prejudice. When a dream unfolds, it is certainly very chaotic, but it is much more similar to life than logical thinking. Let us take an extreme case. If you take a conversation between reasonable people of the present day, you listen and you talk yourself. Think about what is said in the course of, say, half an hour, and whether there is more coherence in the succession of thoughts than there is in dreams, or whether there is as much coherence as in logical thinking. If you were to demand that logical thinking develops there, you would probably be greatly disappointed. The present world presents itself to us entirely in images, so that basically we are actually dreaming all the time. We have yet to bring logic into it. We wrest logic from our prenatal existence; we first bring it into the context of things and thereby also encounter the past in things. We embrace the present with imagination.

When we observe this imaginative life that constantly surrounds us in the sensual present, we can say to ourselves: this imaginative life gives itself to us. We do nothing to it. Just think how hard you had to work to arrive at logical thinking! You didn't have to make any effort to enjoy life, to observe life; it reveals its images to you by itself. Now, that's how it is in life with imagining the images of the ordinary world around us. But all one needs is to acquire the ability to make images – but now through one's own activity, as one otherwise does in thinking – and to experience images through inner effort, as one otherwise does in thinking. Then one not only sees the present in images, but one also extends pictorial imagination to life before birth or before conception, and one sees before birth or before conception. And when you look into these images, then thinking is populated with the images, and then prenatal life becomes reality. We just have to be able to think in images by training the abilities that are spoken of in “How to Know Higher Worlds”, without these images coming to us by themselves, as is the case in ordinary life. When we make this life of images, in which we actually always live in ordinary life, into an inner life, then we look into the spiritual world, and then we do see the way in which our life actually unfolds.

Today, it is considered almost exclusively spiritual when someone – I have spoken about this often – truly despises material life and says: I strive towards the spirit, matter remains far beneath me. This is a weakness, because only the one who does not need to leave matter below him, but who understands matter itself in its effectiveness as spirit, who can recognize everything material as spiritual and everything spiritual, even in its manifestation as material, only he truly attains a spiritual life. This becomes especially significant when we look at thinking and willing. At most, language, which contains a secret genius within it, still has something of what leads to knowledge in this field.

Consider the basis of will in everyday life: you know that it arises from desire; even the most ideal will arises from desire. Now take the coarsest form of desire. What is the coarsest form of desire? Hunger. Therefore, everything that arises from desire is basically always related to hunger. From what I am trying to suggest to you today, you can see that thinking is the other pole, and will therefore behave like the opposite of desire. We can say: if we base desire on the will, we have to base thinking on satiation, on being full, not on hunger.

This actually corresponds to the facts in the deepest sense. If you take our head organization as human beings and the other organization that is attached to it, it is indeed the case that we perceive. What does it mean to perceive? We perceive through our senses. As we perceive, something is actually constantly being removed within us. Something passes from the outside into our inner being. The ray of light that enters our eye actually carries something away. In a sense, a hole is drilled into our own matter (see drawing on page 201). There was matter, but now the beam of light has drilled a hole into it, and now there is hunger. This hunger must be satisfied, and it is satisfied from the organism, from the available food; that is, this hole is filled with the food that is inside us (red). Now we have thought, now we have thought what we have perceived: by thinking, we continually fill the holes that sensory perceptions create in us with satiety that arises from our organism.

It is extremely interesting to observe, when we consider the organization of the head, how we fill the holes that arise in our remaining organism through the ears and eyes, through the sensations of warmth; there are holes everywhere. Man fills himself completely by thinking, by filling that which is there, in the holes (red).

And it is similar with us if we want it to be. Only then it does not work from outside in, so that we are hollowed out, but it works from within. If we want, hollows arise everywhere in us; these must in turn be filled with matter. So that we can say, we receive negative effects, hollowing out effects, both from outside and from inside, and constantly push our matter into them.

These are the most intimate effects, these hollowing effects, which actually destroy all earthly existence in us. Because by receiving the ray of light, by hearing the sound, we destroy our earthly existence. But we react to this, we in turn fill this with earthly existence. So we have a life between the destruction of earthly existence and the filling of earthly existence: luciferic, ahrimanic. The Luciferic is actually constantly striving to partially turn us into something non-material, to completely remove us from our earthly existence; for if he could, Lucifer would like to spiritualize us completely, that is, dematerialize us. But Ahriman is his opponent; he works in such a way that what Lucifer excavates is constantly being filled in again. Ahriman is the constant filler. If you form Lucifer plastically and make Ahriman plastically, you could quite well, if the matter went through in confusion, always push Ahriman into the cavity of Lucifer, or put Lucifer over it. But since there are also cavities inside, you also have to push in. Ahriman and Lucifer are the two opposing forces at work in man. He himself is the state of equilibrium. Lucifer, with continuous dematerialization, results in continuous materialization: Ahriman. When we perceive, that is Lucifer. When we think about what we have perceived: Ahriman. When we form the idea, this or that we should want: Lucifer. When we really want on earth: Ahriman. So we are in the middle of the two. We oscillate back and forth between them, and we must be clear about ourselves: as human beings, we are placed in the most intimate way between the Ahrimanic and the Luciferic. Actually, you only get to know a person when you take these two opposing poles in him into account.

This is an approach that is based neither on an abstract spiritual reality – for this abstract spiritual reality is, after all, nebulous and mystical – nor on a material one, but rather everything that is materially effective is also spiritual at the same time. We are dealing with the spiritual everywhere. And we see through matter in its existence, in its effectiveness, by being able to see the spirit in everything.

I have already told you that imagination comes to us of its own accord in relation to the present. When we develop imagination artificially, we look into the past. When we develop inspiration, we look into the future, just as one calculates into the future by calculating solar or lunar eclipses, not in relation to the details, but to a higher degree in relation to the great laws of the future. And intuition encompasses all three. And we are actually subject to intuition all the time, we just sleep through it. When we sleep, we are completely immersed in the outside world with our ego and our astral body; there we unfold that intuitive activity that one must otherwise consciously unfold in intuition. But in this present organization the human being is too weak to be conscious when he is intuiting; but he does intuit in fact at night. So one can say: Asleep, the human being develops intuition; awake, he develops—to a certain extent, of course—logical thinking; between the two stands inspiration and imagination. When a person comes out of sleep into waking life, his I and his astral body enter into the physical body and the etheric body; what he brings with him is the inspiration to which I have already drawn your attention in previous lectures. We can say: Man is asleep in intuition, awake in logical thinking, when he wakes up he inspires himself, when he falls asleep he imagines. - You can see from this that the activities we mention as the higher activities of knowledge are not alien to ordinary life, but that they are very much present in ordinary life, that they only have to be raised into consciousness if a higher knowledge is to be developed.

It must be pointed out again and again that in the last three to four centuries, external science has summarized a large number of purely material facts and brought them into laws. These facts must first be spiritually penetrated. But it is good - if I may say so, although it sounds paradoxical at first - that materialism was there, otherwise people would have fallen into nebulosity. They would have finally lost all connection with their earthly existence. When materialism began in the 15th century, humanity was in fact in danger of falling prey to Luciferic influences to a high degree, of being hollowed out more and more and more. That is when the Ahrimanic influences came from that time on. And in the last four or five centuries, the Ahrimanic influences have developed to a certain extent. Today they have become very strong and there is a danger that they will overshoot their target if we do not counter them with something that will effectively weaken them: if we do not counter them with the spiritual.

But here it is important to develop the right feeling for the relationship between the spiritual and the material. In the older German way of thinking, there is a poem called “Muspilli”, which was first found in a book dedicated to Louis the German in the 9th century, but which of course dates from a much earlier time. There is something purely Christian in this poem: it presents us with the battle of Elijah with the Antichrist. But the whole way in which this story unfolds, this fight between Elijah and the Antichrist, is reminiscent of the ancient struggles of the sagas, the inhabitants of Asgard with the inhabitants of Jötunheim, the inhabitants of the realm of the giants. It is simply the realm of the Æsir transformed into the realm of Elijah, the realm of the giants into the realm of the Antichrist.

This way of thinking, which we still encounter, conceals the true fact less than the later ways of thinking. The later ways of thinking always talk about duality, about good and evil, about God and the devil, and so on. But these ways of thinking, which were developed in later times, no longer correspond to the earlier ones. Those people who developed the struggle between the Gods' home and the giants' home did not see the same in the Gods as, for example, today's Christian understands in the realm of his God. Instead, these older ideas had, for example, Asgard, the realm of the Gods, above, and Jötunheim, the realm of the giants, below; in the middle, Man unfolds, Midgard. This is nothing other than the same thing in the Germanic-European way that was present in ancient Persia as Ormuzd and Ahriman. There we would have to say in our language: Lucifer and Ahriman. We would have to address Ormuzd as Lucifer and not just as the good God. And that is the great mistake that is made, that one understands this dualism as if Ormuzd were only the good God and his opponent Ahriman the evil God. The relationship is rather like that of Lucifer to Ahriman. And in Middlegard, at the time when this poem “Muspilli” was written, it is still not imagined that The Christ sends his blood down from above – but: Elijah is there, and sends his blood down. And man is placed in the middle. At the time when Louis the German probably wrote this poem into his book, the idea was still more correct than the later one. For later times have committed the strange act of disregarding the Trinity; that is, to understand the upper gods, who are in Asgard, and the lower gods, the giants, who are in the Ahrimanic realm, as the All, and to understand the upper, the Luciferic ones, as the good gods and the others as the evil gods. This was done in later times; in earlier times, this opposition between Lucifer and Ahriman was still properly envisaged, and therefore something like Elijah was placed in the Luciferic realm with his emotional prophecy, with that which he was able to proclaim at that time, because one wanted to place the Christ in Midgard, in that which lies in the middle.

We must go back to these ideas in full consciousness, otherwise we will not come back to the Trinity: to the Luciferic Gods, to the Ahrimanic powers and in between to what the Christ-realm is. Without advancing to this, we will not come to a real understanding of the world.

Do you think that the fact that the old Ormuzd was made into a good god, while he is actually a Luciferic power, a power of light, is a tremendous secret of the historical development of European humanity? But in this way one could have the satisfaction of making Lucifer as bad as possible; because the name Lucifer did not suit Ormuzd, one made Lucifer resemble Ahriman, made a hotchpotch that still has an effect on Goethe in the figure of Mephistopheles, in that there too Lucifer and Ahriman are mixed together, as I have explicitly shown in my little book 'Goethe's Spiritual Nature'. Indeed, European humanity, the humanity of present civilization, has entered into a great confusion, and this confusion ultimately permeates all thinking. It can only be compensated by leading out of duality back into trinity, because everything dual ultimately leads to something in which man cannot live, which he must regard as a polarity, in which he can now really find the balance: Christ is there to balance Lucifer and Ahriman, to balance Ormuzd and Ahriman, and so on.This is the topic I wanted to broach, and we will continue to discuss it in the coming days in various ways.

Elfter Vortrag

Ich werde heute einige Wahrheiten zusammenfassen, die uns dann wiederum dienen werden, um in den nächsten Tagen weitere Ausführungen nach einer gewissen Richtung hin zu geben. Wenn wir unser seelisches Leben ins Auge fassen, so können wir sagen, daß nach dem einen Pol hin in diesem Seelenleben das gedankliche Element, das Denken liegt, nach dem andern Pol hin das Willenselement, zwischen beiden das Gefühlselement, dasjenige, was wir im gewöhnlichen Leben das Fühlen, den Inhalt des Gemütes und so weiter nennen. Im wirklichen seelischen Leben, so wie es sich in uns abspielt in unserem Wachzustande, ist natürlich niemals einseitig bloß das Denken vorhanden oder der Wille, sondern sie sind immer in Verbindung miteinander, sie spielen ineinander. Nehmen wir an, wir verhalten uns im Leben ganz ruhig, so daß wir etwa sagen können, unser Wille sei nach außen hin nicht tätig. Wir müssen dann doch, wenn wir während einer solchen nach außen gerichteten Ruhe denken, uns klar sein darüber, daß Wille waltet in den Gedanken, die wir entfalten: indem wir einen Gedanken mit dem andern verbinden, waltet der Wille in diesem Denken. Also selbst wenn wir gewissermaßen scheinbar bloß kontemplativ sind, bloß denken, so waltet in uns wenigstens innerlich der Wille, und wenn wir uns nicht gerade tobsüchtig verhalten oder nachtwandeln, können wir ja nicht willentlich tätig sein, ohne unsere Willensimpulse von Gedanken durchströmen zu lassen. Gedanken durchziehen immer unsere Willensbetätigung, so daß wir also sagen können: Auch der Wille ist niemals im Seelenleben abgesondert für sich vorhanden. Aber was so abgesondert für sich nicht vorhanden ist, das kann doch verschiedenen Ursprunges sein. Und so ist auch der eine Pol unseres Seelenlebens, das Denken, ganz andern Ursprunges als das Willensleben.

Schon wenn wir nur die alltäglichen Lebenserscheinungen betrachten, werden wir ja finden, wie das Denken eigentlich sich immer auf etwas bezieht, was da ist, was Voraussetzungen hat. Das Denken ist zumeist ein Nachdenken. Auch wenn wir vordenken, wenn wir also uns etwas vornehmen, das wir durch den Willen dann ausführen, so liegen ja einem solchen Vordenken Erfahrungen zugrunde, nach denen wir uns richten. Auch dieses Denken ist in gewisser Beziehung natürlich ein Nachdenken. Der Wille kann sich nicht richten auf dasjenige, was schon da ist. Da würde er ja selbstverständlich immer zu spät kommen. Der Wille kann sich einzig und allein richten auf das, was da kommen soll, auf das Zukünftige. Kurz, wenn Sie ein wenig über das Innere des Gedankens, des Denkens und über das Innere des Willens nachdenken, Sie werden finden, das Denken bezieht sich auch schon im gewöhnlichen Leben mehr auf die Vergangenheit, der Wille bezieht sich auf die Zukunft. Das Gemüt, das Fühlen, steht zwischen beiden. Wir begleiten mit Gefühl unsere Gedanken. Gedanken freuen uns, stoßen uns ab. Aus unserem Gefühl heraus führen wir unsere Willensimpulse ins Leben. Fühlen, der Gemütsinhalt, steht zwischen dem Denken und dem Wollen mitten drinnen.

Aber so wie es schon im gewöhnlichen Leben, wenn auch nur andeutungsweise der Fall ist, so steht es auch in der großen Welt. Und da müssen wir sagen: Dasjenige, was unsere Denkkraft ausmacht, was das ausmacht, daß wir denken können, daß die Möglichkeit des Gedankens in uns ist, das verdanken wir dem Leben vor unserer Geburt beziehungsweise vor unserer Empfängnis. Es ist im Grunde genommen in dem kleinen Kinde, das uns entgegentritt, schon im Keime all die Gedankenfähigkeit vorhanden, die der Mensch überhaupt in sich entwickelt. Das Kind verwendet die Gedanken nur — Sie wissen das aus Vorträgen, die ich schon gehalten habe - als Richtkräfte zum Aufbauen seines Leibes. Namentlich in den ersten sieben Lebensjahren, bis zum Zahnwechsel hin, verwendet das Kind die Gedankenkräfte zum Aufbau seines Leibes als Richtkräfte. Dann kommen sie immer mehr und mehr als eigentliche Gedankenkräfte heraus. Aber sie sind eben als Gedankenkräfte durchaus veranlagt im Menschen, wenn er das physische, das irdische Leben berritt.

Dasjenige, was als Willenskräfte sich entwickelt - eine unbefangene Beobachtung ergibt das ohne weiteres -, das ist beim Kinde eigentlich wenig mit dieser Gedankenkraft verbunden. Beobachten Sie nur das zappelnde, sich bewegende Kind in den ersten Lebenswochen, dann werden Sie sich schon sagen: Dieses Zappelnde, dieses chaotisch SichBewegende, das ist von dem Kinde erst erworben dadurch, daß seine Seele und sein Geist von der physischen Außenwelt her mit physischer Leiblichkeit umkleidet worden sind. In dieser physischen Leiblichkeit, die wir erst nach und nach entwickeln seit der Konzeption und seit der Geburt, da liegt zunächst der Wille, und es besteht ja die Entwickelung des kindlichen Lebens darinnen, daß allmählich der Wille gewissermaßen eingefangen wird von den Denkkräften, die wir schon durch die Geburt ins physische Dasein mitbringen. Beobachten Sie nur, wie das Kind zunächst ganz sinnlos, wie es eben aus der Regsamkeit des physischen Leibes herauskommt, seine Glieder bewegt, und wie nach und nach, ich möchte sagen, der Gedanke hineinschlägt in diese Bewegungen, so daß sie sinnvoll werden. Es ist also ein Hineinpressen, ein Hineinstoßen des Denkens in das Willensleben, das ganz und gar in der Hülle, die den Menschen umgibt, lebt, wenn er geboren beziehungsweise wenn er empfangen wird. Es ist dieses Willensleben ganz und gar darinnen enthalten.

So daß wir schematisch etwa den Menschen so zeichnen können, daß wir sagen, er bringt sich sein Gedankenleben mit, indem er heruntersteigt aus der geistigen Welt. Ich will das schematisch so andeuten (siehe Zeichnung, gelb). Und er setzt das Willensleben an in der Leiblichkeit, die ihm durch die Eltern gegeben wird (rot). Dadrinnen sitzen die Willenskräfte, die sich chaotisch äußern. Und dadrinnen sitzen die Gedankenkräfte (Pfeile), die zunächst als Richtkräfte dienen, um eben den Willen in seiner Leiblichkeit in der richtigen Weise zu durchgeistigen.

Diese Willenskräfte, sie nehmen wir dann wahr, wenn wir durch den Tod in die geistige Welt hinübergehen. Da sind sie aber im höchsten Maße geordnet. Da tragen wir sie hinüber durch die Todespforte in das geistige Leben. Die Gedankenkräfte, die wir mitbringen aus dem übersinnlichen Leben in das Erdenleben, die verlieren wir eigentlich im Verlauf des Erdenlebens.

Bei Menschenwesen, die früh sterben, ist es etwas anders, wir wollen jetzt zunächst vom normalen Menschenwesen sprechen. Das normale Menschenwesen, das über die fünfziger Jahre alt wird, das hat eigentlich im Grunde genommen die wirklichen Gedankenkräfte, die aus dem früheren Leben mitgebracht werden, schon verloren und sich eben die Richtungskräfte des Willens bewahrt, die dann durch den Tod hinübergetragen werden in das Leben, das wir betreten, wenn wir durch des Todes Pforte gehen.

Man kann ja annehmen, daß jetzt in einem der Gedanke sitzt: Ja, wenn man also über fünfzig Jahre alt geworden ist, dann hat man sein Denken verloren! - In einem gewissen Sinne ist das sogar für die meisten Menschen, die sich heute für nichts Geistiges interessieren, durchaus der Fall. Ich möchte nur einmal, daß Sie wirklich darauf ausgehen, zu registrieren, wieviel ursprüngliche, originelle Gedankenkräfte durch diejenigen Menschen heute hervorgebracht werden, die über fünfzig Jahre alt geworden sind! Es sind in der Regel die automatisch sich fortbewegenden Gedanken der früheren Jahre, die sich im Leibe abgedrückt haben, und der Leib bewegt sich dann automatisch fort. Er ist ja ein Bild des Gedankenlebens, und der Mensch, der rollt so nach dem Gesetz der Trägheit, nicht wahr, in dem alten Gedankentrott weiter fort. Man kann sich heute kaum vor diesem Fortlaufen im alten Gedankentrott anders bewahren, als daß man auch während des Lebens solche Gedanken aufnimmt, welche geistiger Natur sind, welche ähnlich sind den Gedankenkräften, in die wir versetzt waren vor unserer Geburt. So daß in der Tat immer mehr die Zeit heranrückt, wo die alten Leute bloße Automaten sein werden, wenn sie sich nicht bequemen, Gedankenkräfte aus der übersinnlichen Welt aufzunehmen. Natürlich, automatisch kann der Mensch sich weiter denkend betätigen, es kann so ausschauen, als ob er dächte. Aber es ist nur ein automatisches Fortbewegen der Organe, in die sich die Gedanken hineingelegt haben, hineinverwoben haben, wenn nicht der Mensch erfaßt wird von jenem jugendlichen Element, das da kommt, wenn wir Gedanken aus der Geisteswissenschaft aufnehmen. Dieses Aufnehmen von Gedanken aus der Geisteswissenschaft ist eben durchaus nicht irgendein Theoretisieren, sondern es greift schon ganz tief im menschlichen Leben ein.

Besondere Bedeutung aber gewinnt die Sache, wenn wir jetzt des Menschen Verhältnis zur umliegenden Natur ins Auge fassen. Ich verstehe jetzt unter Natur all das, was uns umgibt für unsere Sinne, dem wir also ausgesetzt sind vom Aufwachen bis zum Einschlafen. Das kann man in einer gewissen Weise in der folgenden Art betrachten. Man kann sich das einmal vor Augen führen — ich meine vor geistige Augen -, was man so sieht. Wir nennen es den Sinnesteppich. Ich will es schematisch so aufzeichnen. Hinter allem, was man sieht, hört, als Wärme wahrnimmt, die Farben in der Natur und so weiter — ich zeichne ein Auge als Schema für das, was da wahrgenommen wird —, hinter diesem Sinnesteppich ist etwas. Die Physiker oder die Menschen der gegenwärtigen Weltanschauung sagen: Dahinter sind Atome und die wirbeln -, und nachher, nicht wahr, da wirbeln sie weiter, da ist gar kein Sinnesteppich, sondern irgendwie im Auge oder im Gehirn oder irgendwo oder auch nicht irgendwo, da rufen sie dann die Farben und die Töne und so weiter hervor. Nun stellen Sie sich aber, bitte, ganz unbefangen einmal vor, daß Sie anfangen zu denken über diesen Sinnesteppich. Wenn Sie anfangen zu denken und nicht von der Illusion ausgehen, Sie könnten dieses riesige Heer von Atomen konstatieren, das da von den Chemikern so in militärischer Denkweise angeordnet wird, sagen wir zum Beispiel, da steht Unteroffizier C, dann zwei Gemeine, C, O, O, und dann noch ein Gemeiner als ein H; nicht wahr, so haben wir das ja militärisch angeordnet: Äther, Atome und so weiter. Nun, wenn man, wie gesagt, sich dieser Illusion nicht hingibt, sondern stehenbleibt bei der Wirklichkeit, dann weiß man: Der Sinnesteppich ist ausgebreitet, da draußen sind die Sinnesqualitäten, und das, was ich noch über dasjenige, was in den Sinnesqualitäten liegt, mit dem Bewußtsein umfasse, das sind eben Gedanken. Es ist in Wirklichkeit nichts hinter diesem Sinnesteppich als Gedanken (blau). Ich meine, hinter dem, was wir in der physischen Welt haben, ist nichts anderes da als Gedanken. Daß diese von Wesen getragen werden, darüber werden wir noch sprechen. Aber man kommt zu dem, was wir in unserem Bewußtsein haben, nur dahinter mit den Gedanken. Die Kraft aber, zu denken, die haben wir aus unserem vorgeburtlichen Leben beziehungsweise aus dem Leben vor unserer Empfängnis. Warum ist es denn nun, daß wir durch diese Kraft hinter den Sinnesteppich kommen?

Versuchen Sie nur einmal, sich recht vertraut zu machen mit dem Gedanken, den ich eben angeschlagen habe, versuchen Sie sich die Frage ordentlich vorzulegen auf Grundlage dessen, was wir nun gerade wiederum angedeutet haben, was wir in vielen Zusammenhängen schon betrachtet haben. Warum ist es so, daß wir hinter den Sinnesteppich mit unseren Gedanken hinuntergelangen, wenn unsere Gedanken doch aus unserem vorgeburtlichen Leben stammen? Sehr einfach: weil dahinter dasjenige ist, was gar nicht in der Gegenwart ist, sondern was in der Vergangenheit ist, was der Vergangenheit angehört. Das, was unter dem Sinnesteppich ist, ist in der Tat ein Vergangenes, und wir sehen das nur richtig, wenn wir es als ein Vergangenes anerkennen. Die Vergangenheit wirkt herein in unsere Gegenwart, und aus der Vergangenheit heraus sprießt dasjenige, was uns in der Gegenwart erscheint. Stellen Sie sich eine Wiese vor, die beblumt ist. Sie sehen das Gras als grüne Decke, Sie sehen die blumige Ausschmückung der Wiese. Das ist Gegenwart, aber das wächst aus der Vergangenheit hervor. Und wenn Sie durch das hindurchdenken, dann haben Sie darunter nicht eine atomistische Gegenwart, dann haben Sie in Wirklichkeit darunter die Vergangenheit als verwandt mit dem, was von Ihnen selber aus der Vergangenheit herstammt.

Es ist interessant: Wenn wir über die Dinge nachzudenken beginnen, so enthüllt sich uns von der Welt gar nicht die Gegenwart, sondern es enthüllt sich die Vergangenheit. Was ist Gegenwart? Die Gegenwart hat gar keine logische Struktur. Der Sonnenstrahl fällt auf irgendeine Pflanze, er glänzt dort; im nächsten Augenblick, wenn die Richtung des Sonnenstrahls eine andere ist, glänzt es nach einer andern Richtung. Das Bild ändert sich in jedem Augenblick. Die Gegenwart ist eine solche, daß wir sie nicht umfassen können mit Mathematik, nicht mit der bloßen Gedankenstruktur. Was wir mit der bloßen Gedankenstruktur umfassen, ist Vergangenheit, die in der Gegenwart fortdauert.

Das ist etwas, was dem Menschen sich enthüllen kann als eine große, als eine bedeutsame Wahrheit: Denkst du, so denkst du im Grunde genommen nur die Vergangenheit; spinnst du Logisches, denkst du im Grunde genommen über dasjenige nach, was vergangen ist. - Wer diesen Gedanken erfaßt, der wird auch in dem Vergangenen keine Wunder mehr suchen. Denn indem sich das Vergangene in die Gegenwart hereinspinnt, muß es eben in der Gegenwart sein wie es als Vergangenes ist. Denken Sie, wenn Sie gestern Kirschen gegessen haben, so ist das eine vergangene Handlung; Sie können sie nicht ungeschehen machen, weil sie eine vergangene Handlung ist. Wenn aber die Kirschen die Gewohnheit hätten, bevor sie in Ihrem Munde verschwinden, zuerst ein Zeichen irgendwohin zu machen, so würde dieses Zeichen bleiben. Sie könnten an diesem Zeichen nichts ändern. Wenn da jede Kirsche, nachdem Sie gestern Kirschen gegessen haben, ihre Vergangenheit in Ihren Mund hineinregistriert hätte, und nun einer kommen würde und fünf ausstreichen wollte, könnte er sie zwar ausstreichen, aber die Tatsache würde sich nicht ändern. Ebensowenig können Sie irgendein Wunder verrichten in bezug auf alles, was Naturerscheinungen sind, denn die sind alle Hereinragungen aus dem Vergangenen. Und alles, was wir mit Naturgesetzen umfassen können, ist schon vergangen, ist kein Gegenwärtiges mehr. Das Gegenwärtige können Sie nicht anders als durch Bilder erfassen, das ist ein Fluktuierendes. Wenn ein Körper hier aufleuchtet, so entsteht ja ein Schatten. Sie müssen gewissermaßen den Schatten sich richtig begrenzen lassen und so weiter. Sie können den Schatten konstruieren. Daß der Schatten wirklich entsteht, das kann nur durch die Hingabe an das Bild eruiert werden. So daß man sagen kann: Schon im gewöhnlichen Leben bezieht sich das Begrenzen, ich könnte auch sagen, das logische Denken, auf die Vergangenheit. Und die Imagination, die bezieht sich auf die Gegenwart. In bezug auf die Gegenwart hat der Mensch immer Imaginationen.

Denken Sie doch nur einmal, wenn Sie logisch leben wollten in der Gegenwart! Nicht wahr, logisch leben heißt, einen Begriff aus dem andern hervorholen, gesetzmäßig von einem Begriff zum andern übergehen. Nun, versetzen Sie sich nur einmal ins Leben. Sie sehen irgendein Ereignis: ist das nächste logisch darangegliedert? Können Sie das nächste Ereignis logisch aus dem vorhergehenden ableiten? Wenn Sie das Leben überblicken, ist es nicht in seinen Bildern ähnlich wie der Traum? Die Gegenwart ist ähnlich wie der Traum, und nur daß sich in die Gegenwart die Vergangenheit hineinmischt, das bewirkt, daß diese Gegenwart gesetzmäßig verläuft, logisch verläuft. Und wenn Sie irgend etwas Zukünftiges in der Gegenwart erahnen wollen, ja, wenn Sie nur irgend etwas denken wollen, was Sie in der Zukunft verrichten wollen, dann ist das ja zunächst ganz ungegenständlich bei Ihnen vorgegangen. Was Sie heute Abend erleben werden, steht nicht als Bild in Ihnen, sondern als etwas, was unbildlicher als ein Bild ist. Es steht höchstens als Inspiration in Ihnen. Die Inspiration bezieht sich auf die Zukunft. Logisches Denken: Vergangenheit Imagination: Gegenwart Intuition Inspiration: Zukunft.

| Logisches Denken: | Vergangenheit | Intuition |

| Imagination: | Gegenwart | |

| Inspiration: | Zukunft |

Wir können uns auch durch ein einfaches Schema klarmachen, um was es sich da handelt. Wenn der Mensch - ich will ihn hier durch dieses Auge charakterisiert haben (siehe Zeichnung Seite 198) - auf den Sinnesteppich hinblickt, so sieht er ihn in seinen sich verwandelnden Bildern, aber er kommt jetzt und bringt Gesetze in diese Bilder hinein. Er bildet sich eine Naturwissenschaft aus den wechselnden Bildern der Sinneswelt. Er bildet sich eine Fachwissenschaft. Aber denken Sie einmal nach, wie diese Naturwissenschaft ausgebildet wird. Man untersucht, man untersucht denkend. Sie können unmöglich, wenn Sie eine Wissenschaft ausbilden wollen über das, was sich als Sinnesteppich ausbreitet, eine Wissenschaft, die in logischen Gedanken verläuft, diese logischen Gedanken aus der Außenwelt heraus gewinnen. Wenn das, was als Gedanken - und Naturgesetze sind ja auch Gedanken -, wenn das, was als Gesetze der Außenwelt erkannt wird, aus der Außenwelt selbst folgte, ja, dann wäre ja nicht notwendig, daß wir irgend etwas lernten über die Außenwelt, dann müßte derjenige, der zum Beispiel sich dieses Licht da ansieht, ganz genau die elektrischen Gesetze und so weiter wissen, wie der andere, der es gelernt hat! Ebensowenig weiß der Mensch, wenn er es nicht gelernt hat, irgend etwas, sagen wir über die Beziehung eines Kreisbogens zum Radius und so weiter. Da bringen wir die Gedanken, die wir in die Außenwelt hineintragen, aus unserem Inneren hervor.

Ja, es ist so: Dasjenige, was wir als Gedanken in die Außenwelt hineintragen, bringen wir aus unserem Inneren hervor. Wir sind zunächst dieser Mensch, der als Hauptesmensch konstruiert ist. Dieser sieht auf den Sinnesteppich hin. Im Sinnesteppich drinnen ist dasjenige, was wir durch Gedanken erreichen (siehe Zeichnung Seite 198, weiß) und zwischen diesem und zwischen dem, was wir in unserem eigenen Inneren haben, was wir nicht wahrnehmen, ist eine Verbindung, gewissermaßen eine unterirdische Verbindung. Daher kommt es, daß wir dasjenige, was wir in der Außenwelt nicht wahrnehmen, weil es in uns hineinragt, aus unserem Inneren in Form des Gedankenlebens hervorholen und in die Außenwelt hineinlegen. So ist es schon mit dem Zählen. Die Außenwelt zählt uns gar nichts vor; die Gesetze des Zählens liegen in unserem eigenen Inneren. Aber daß das stimmt, rührt davon her, daß zwischen diesen Anlagen, die da sind in der Außenwelt und unseren eigenen irdischen Gesetzen, ein unterirdischer Zusammenhang ist, ein unterkörperlicher Zusammenhang, und so holen wir die Zahl aus unserem Inneren heraus. Die paßt dann zu dem, was draußen ist. Aber der Weg ist nicht durch unsere Augen, nicht durch unsere Sinne, sondern der Weg ist durch unseren Organismus. Und dasjenige, was wir als Mensch ausbilden, das bilden wir als ganzer Mensch aus. Es ist nicht wahr, daß wir durch die Sinne irgendein Naturgesetz erfassen; wir erfassen es als ganzer Mensch.

Diese Dinge muß man in Erwägung ziehen, wenn man das Verhältnis des Menschen zur Umwelt in der richtigen Weise sich zum Gemüte führen will. Wir sind ja fortwährend in Imaginationen drinnen, und man brauchte nur unbefangen das Leben mit dem Traum zu vergleichen. Wenn der Traum abläuft, so läuft er gewiß sehr chaotisch ab, aber er ist dem Leben viel ähnlicher als das logische Denken. Nehmen wir einen extremen Fall. Wenn Sie - na, ich will sogar eine Unterhaltung unter vernünftigen Menschen der Gegenwart annehmen: Sie hören zu, reden selber mit. Denken Sie einmal nach, was da, sagen wir, im Laufe einer halben Stunde hintereinander geredet wird, ob mehr Zusammenhang darinnen liegt, wenn Sie es in seiner Aufeinanderfolge betrachten, als im Traume ist, oder ob es ein solcher Zusammenhang ist wie im logischen Denken. Wenn Sie verlangen würden, daß sich da logisches Denken entwickelt, dann würden Sie wahrscheinlich zu großen Enttäuschungen kommen. Die gegenwärtige Welt tritt uns durchaus in Bildern entgegen, so daß wir eigentlich im Grunde genommen fortwährend träumen. Die Logik müssen wir ja erst hineinbringen. Die Logik entringen wir uns aus unserer Vorgeburtlichkeit; wir bringen sie erst in den Zusammenhang der Dinge hinein und treffen dadurch auch auf das Vergangene in den Dingen. Die Gegenwart umfassen wir mit Imaginationen.

Wenn wir dieses imaginative Leben, das uns in der sinnlichen Gegenwart fortwährend umgibt, betrachten, so können wir uns sagen: Es gibt sich uns dieses imaginative Leben. Wir tun nichts dazu. - Denken Sie nur einmal, wie Sie sich haben anstrengen müssen, um zum logischen Denken zu kommen! Das Leben zu genießen, das Leben zu betrachten, haben Sie sich gar nicht anzustrengen brauchen, das enthüllt seine Bilder von selbst vor Ihnen. Nun, da haben wir es eben gut im Leben in bezug auf das Bildervorstellen der gewöhnlichen Umwelt. Nichts anderes braucht man aber, als nun auch die Fähigkeit sich zu erwerben, so Bilder zu machen - aber jetzt durch eigene Tätigkeit, wie man es sonst im Denken tut - und Bilder zu erleben durch innere Anstrengung, wie es sonst beim Denken geschieht. Dann sieht man nicht nur die Gegenwart in Bildern, dann dehnt man das bildliche Vorstellen auch aus auf das Leben vor der Geburt oder vor der Empfängnis, dann sieht man vor die Geburt hin oder vor die Empfängnis. Und wenn man da in Bildern hineinschaut, dann bevölkert sich das Denken mit den Bildern, und dann wird das vorgeburtliche Leben Realität. Wir müssen uns nur durch Ausbildung derjenigen Fähigkeiten, von denen gesprochen wird in «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?», angewöhnen können, in Bildern zu denken, ohne daß diese Bilder sich uns, wie das im gewöhnlichen Leben der Fall ist, von selber geben. Wenn wir dieses Bilderleben, in dem wir eigentlich immer drinnenstehen im gewöhnlichen Leben, zu einem Innenleben machen, dann schauen wir in die geistige Welt hinein, und dann erblicken wir allerdings die Art und Weise, wie unser Leben eigentlich verläuft.

Heute betrachtet man es ja ziemlich ausschließlich als geistig, wenn jemand - ich habe darüber öfter gesprochen — das materielle Leben richtig verachtet und sagt: Ich strebe zum Geist, Materie bleibt tief unter mir. — Das ist eine Schwäche, denn nur derjenige gelangt wirklich zu einem spirituellen Leben, der nicht die Materie unter sich zu lassen braucht, sondern der die Materie selbst in ihrer Wirksamkeit als Geist begreift, der alles Materielle als ein Geistiges und alles Geistige, auch in seiner Offenbarung als Materielles, erkennen kann. Das wird insbesondere bedeutsam, wenn wir auf Denken und Wollen hinblicken. Höchstens noch die Sprache, die ja einen geheimen Genius in sich enthält, die hat noch etwas von dem, was auf diesem Felde zur Erkenntnis führt.

Beachten Sie das Wollen in seiner Grundlage im gewöhnlichen Leben: Sie wissen, es geht hervor aus dem Begehren; selbst das idealste Wollen geht aus dem Begehren hervor. Nun, nehmen Sie die gröbste Form des Begehrens. Die gröbste Form des Begehrens, welche ist sie? Der Hunger. Daher ist auch alles, was aus dem Begehren hervorgeht, im Grunde immer verwandt dem Hunger. Aus dem, was ich Ihnen heute andeuten will, können Sie ja entnehmen, daß das Denken der andere Pol ist, er wird sich daher wie das Entgegengesetzte zum Begehren verhalten. Wir können sagen: Wenn wir das Begehren dem Wollen zugrunde legen, haben wir dem Denken die Sättigung zugrunde zu legen, die Gesättigtheit, nicht den Hunger.

Das entspricht eigentlich im tiefsten Sinne dem Tatbestand. Wenn Sie unsere Hauptesorganisation als Menschen nehmen und die andere Organisation, die daran hängt, so ist es in der Tat so: Wir nehmen wahr. Was heißt das, wir nehmen wahr? Wir nehmen wahr durch unsere Sinne. Indem wir wahrnehmen, wird eigentlich fortwährend etwas in uns abgetragen. Es geht etwas von außen in unser Inneres. Der Lichtstrahl, der in unser Auge dringt, der trägt eigentlich etwas ab. Es wird gewissermaßen in unsere eigene Materie ein Loch hineingebohrt (siehe Zeichnung Seite 201). Da war Materie, jetzt hat der Lichtstrahl ein Loch hineingebohrt, jetzt ist Hunger vorhanden. Dieser Hunger muß gesättigt werden, er wird aus dem Organismus, aus der vorhandenen Nahrung heraus gesättigt; das heißt, dieses Loch füllt sich aus mit der Nahrung, die in uns ist (rot). Jetzt haben wir gedacht, jetzt haben wir dasjenige, was wir wahrgenommen haben, gedacht: indem wir denken, füllen wir fortwährend die Löcher, welche die Sinneswahrnehmungen in uns bilden, mit Sättigung aus, die aus unserem Organismus aufsteigt.

Es ist außerordentlich interessant zu beobachten, wenn wir die Kopforganisation ins Auge fassen, wie wir aus unserem übrigen Organismus heraus durch die Löcher, die da entstehen, durch Ohren und durch Augen, durch die Wärmeempfindungen, da sind überall Löcher, hineinlegen die Materie. Der Mensch füllt sich ganz aus, indem er denkt, indem er dasjenige, was da ausgelocht ist, ausfüllt (rot).

Und wenn wir wollen, so ist es ähnlich. Nur wirkt es dann nicht von außen herein, so daß wir ausgehöhlt werden, sondern da wirkt es von innen. Wenn wir wollen, entstehen überall in uns Höhlungen; die müssen wiederum mit Materie sich ausfüllen. So daß wir sagen können, wir bekommen negative Wirkungen, aushöhlende Wirkungen, sowohl von außen wie von innen und schieben fortwährend unsere Materie hinein.

Das sind die intimsten Wirkungen, diese aushöhlenden Wirkungen, die eigentlich in uns das ganze Erdensein vernichten. Denn indem wir den Lichtstrahl empfangen, indem wir den Ton hören, vernichten wir unser Erdendasein. Wir reagieren aber darauf, wir füllen das wiederum mit Erdendasein aus. Wir haben also ein Leben zwischen Vernichtung des Erdendaseins und Ausfüllen des Erdendaseins: luziferisch, ahrimanisch. Das Luziferische ist eigentlich fortwährend bestrebt, partiell aus uns ein Nichtmaterielles zu machen, uns ganz hinwegzuheben aus dem Erdendasein; Luzifer möchte nämlich, wenn er könnte, uns ganz vergeistigen, das heißt entmaterialisieren. Aber Ahriman ist sein Gegner; der wirkt so, daß fortwährend dasjenige, was Luzifer ausgräbt, wiederum ausgefüllt wird. Ahriman ist der fortwährende Ausfüller. Wenn Sie den Luzifer plastisch gestalten und den Ahriman plastisch machen, so könnten Sie ganz gut, wenn die Materie durcheinander durchginge, Ahriman immer hineindrängen in die Höhlung von Luzifer, oder Luzifer drüberstülpen. Aber da innen auch Höhlungen sind, muß man auch hineinstülpen. Ahriman und Luzifer, das sind die beiden entgegengesetzten Kräfte, die im Menschen wirken. Er selbst ist die Gleichgewichtslage. Luzifer, mit fortwährendem Entmaterialisieren, ergibt fortwährend Materialisieren: Ahriman. Wenn wir wahrnehmen, das ist Luzifer. Wenn wir über das Wahrgenommene denken: Ahriman. Wenn wir die Idee bilden, dieses oder jenes sollen wir wollen: Luzifer. Wenn wir wirklich wollen auf der Erde: Ahriman. So stehen wir zwischen den beiden darinnen. Wir pendeln zwischen ihnen hin und her, und wir müssen uns schon klar sein: Wir sind als Menschen zwischen das Ahrimanische und das Luziferische in der intimsten Weise hineingestellt. Eigentlich lernt man den Menschen nur kennen, wenn man diese zwei entgegengesetzten Pole an ihm in Betracht zieht.

Da haben Sie eine Betrachtungsweise, welche durchaus weder auf ein abstraktes Geistiges bloß geht — denn dieses abstrakte Geistige ist ja ein nebulos Mystisches —, noch auf ein Materielles, sondern alles, was materielle Wirkung ist, ist zu gleicher Zeit geistig. Wir haben es überall mit Geistigem zu tun. Und wir durchschauen die Materie in ihrem Dasein, in ihrer Wirksamkeit, indem wir überall den Geist hineinschauen können.

Ich habe Ihnen gesagt: Die Imagination kommt uns in bezug auf die Gegenwart von selbst. Wenn wir die Imagination künstlich ausbilden, so schauen wir in die Vergangenheit hinein. Wenn wir die Inspiration ausbilden, schauen wir in die Zukunft hinein, so wie man in die Zukunft hinein rechnet, indem man etwa Sonnenfinsternisse oder Mondenfinsternisse berechnet, nicht in bezug auf die Einzelheiten, aber auf die großen Gesetzmäßigkeiten der Zukunft in einem höheren Grade. Und die Intuition faßt alle drei zusammen. Und der Intuition sind wir eigentlich fortwährend unterworfen, nur verschlafen wir das. Wenn wir schlafen, sind wir mit unserem Ich und mit unserem astralischen Leibe ganz in der Außenwelt drinnen; wir entfalten da jene intuitive Tätigkeit, die man sonst bewußt entfalten muß in der Intuition. Nur ist der Mensch in dieser gegenwärtigen Organisation zu schwach, um dann bewußt zu sein, wenn er intuitiert; aber er intuitiert in der Tat in der Nacht. So daß man sagen kann: Schlafend entwickelt der Mensch die Intuition, wachend entwickelt er - bis zu einem gewissen Grade natürlich — das logische Denken; zwischen beiden steht Inspiration und Imagination. Indem der Mensch aus dem Schlafe herüberkommt ins wachende Leben, gehen sein Ich und sein astralischer Leib in den physischen Leib und in den Ätherleib herein; dasjenige, was er sich da mitbringt, ist die Inspiration, auf die ich Sie schon in den verflossenen Vorträgen aufmerksam gemacht habe. Wir können sagen: Schlafend ist der Mensch in Intuition, wachend im logischen Denken, aufwachend inspiriert er sich, einschlafend imaginiert er. - Sie sehen daraus, daß diejenigen Tätigkeiten, die wir anführen als die höheren Tätigkeiten der Erkenntnis, dem gewöhnlichen Leben nicht fremd sind, sondern daß sie durchaus im gewöhnlichen Leben vorhanden sind, daß sie nur ins Bewußtsein heraufgehoben werden müssen, wenn eine höhere Erkenntnis entwickelt werden soll.

Worauf immer wieder hingewiesen werden muß, das ist, daß in den letzten drei bis vier Jahrhunderten die äußere Wissenschaft eine große Summe von rein materiellen Tatsachen zusammengefaßt und in Gesetze gebracht hat. Diese Tatsachen müssen erst wiederum geistig durchdrungen werden. Aber es ist gut - wenn ich so sagen darf, obwohl es zunächst paradox klingt —, daß der Materialismus da war, sonst wären die Menschen in die Nebulosität herein verfallen. Sie hätten zuletzt überhaupt allen Zusammenhang mit dem Erdendasein verloren. Als im 15. Jahrhundert der Materialismus begann, war nämlich die Menschheit im hohen Grade daran, luziferischen Einflüssen zu verfallen, nach und nach immer mehr und mehr ausgehöhlt zu werden. Da kamen eben die ahrimanischen Einflüsse seit jener Zeit. Und in den letzten vier, fünf Jahrhunderten haben sich die ahrimanischen Einflüsse bis zu einer gewissen Höhe entwickelt. Heute sind sie sehr stark geworden und es ist die Gefahr vorhanden, daß sie über ihr Ziel hinausschießen, wenn wir ihnen nicht entgegenhalten dasjenige, was sie gewissermaßen erlahmen macht: wenn wir ihnen nicht das Geistige entgegenhalten.

Aber da handelt es sich darum, daß man gerade für das Verhältnis des Geistigen zum Materiellen das richtige Gefühl entwickelt. Es gibt in der älteren deutschen Denkweise ein Gedicht, das man «Muspilli» genannt hat, das sich zuerst in einem Buche gefunden hat, das Ludwig dem Deutschen im 9. Jahrhundert gewidmet war, das aber natürlich aus viel früherer Zeit stammt. In diesem Gedicht liegt etwas rein Christliches vor: es wird uns der Kampf des Elias mit dem Antichrist vorgeführt. Aber die ganze Art und Weise, wie diese Erzählung verläuft, dieser Kampf des Elias mit dem Antichrist, erinnert an die alten Kämpfe der Sagen, der Bewohner von Asgard mit den Bewohnern von Jötunheim, den Bewohnern des Riesenreiches. Es ist einfach das Reich der Asen in das Reich des Elias verwandelt worden, das Reich der Riesen in das Reich des Antichrist.

Diese Denkweise, die uns da noch entgegentritt, die verhüllt die wahre Tatsache weniger als die späteren Denkweisen. Die späteren Denkweisen, die reden eigentlich immer von einer Dualität, von dem Guten und Bösen, von Gott und dem Teufel und so weiter. Aber diese Denkweisen, die man in der späteren Zeit ausgebildet hat, stimmen nicht mehr zu den früheren. Jene Menschen, die den Kampf ausgebildet haben zwischen dem Götterheim und dem Riesenheim, die haben in den Göttern nicht dasselbe gesehen, wie es etwa der heutige Christ unter dem Reiche seines Gottes versteht, sondern diese älteren Vorstellungen haben zum Beispiel oben Asgard, das Reich der Götter gehabt, und unten Jötunheim, das Reich der Riesen; in der Mitte entfaltet sich der Mensch, Midgard. Das ist nichts anderes als in germanisch-europäischer Art dasselbe, was im alten Persien als Ormuzd und Ahriman vorhanden war. Da müßten wir nun in unserer Sprache sagen: Luzifer und Ahriman. Wir müßten Ormuzd als Luzifer ansprechen und nicht etwa bloß als den guten Gott. Und das ist der große Irrtum, der begangen wird, daß man diesen Dualismus so faßt, als wenn Ormuzd nur der gute Gott wäre und sein Gegner Ahriman der böse Gott. Das Verhältnis ist vielmehr das wie von Luzifer zu Ahriman. Und in Mittelgard, da wird in der Zeit, in der dieses Gedicht «Muspilli» abgefaßt ist, noch ganz richtig nicht vorgestellt: Der Christus läßt oben sein Blut herunterstrahlen -, sondern: Elias ist da, der sein Blut herunterstrahlen läßt. - Und der Mensch wird in die Mitte hineingestellt. Die Vorstellung war in der Zeit, in der wahrscheinlich Ludwig der Deutsche dieses Gedicht in sein Buch hineingeschrieben hat, noch eine richtigere als die spätere. Denn die spätere Zeit hat das Sonderbare begangen, die Trinität außer acht zu lassen; das heißt, die oberen Götter, die in Asgard sind, und die unteren Götter, die Riesengötter, die im ahrimanischen Reich sind, diese als das All aufzufassen, und zwar die oberen, die luziferischen, als die guten Götter und die andern als die bösen Götter. Das hat die spätere Zeit gemacht; die frühere Zeit hat noch diesen Gegensatz zwischen Luzifer und Ahriman richtig ins Auge gefaßt, und daher so etwas wie den Elias in das luziferische Reich hineingestellt mit seiner emotionellen Prophetie, mit demjenigen, was er dazumal verkündigen konnte, weil man den Christus hineinstellen wollte in Mittelgard, in dasjenige, was in der Mitte liegt.

Wir müssen wiederum zurück zu diesen Vorstellungen in vollem Bewußtsein, sonst werden wir, wenn wir nur von der Dualität zwischen Gott und dem Teufel sprechen, nicht wiederum zu der Trinität kommen: zu den luziferischen Göttern, zu den ahrimanischen Mächten und dazwischen zu dem, was das Christus-Reich ist. Ohne daß wir dazu vorrücken, kommen wir nicht zu einem wirklichen Verständnis der Welt. Denken Sie, es ist darin ein ungeheures Geheimnis der geschichtlichen Entwickelung der europäischen Menschheit, daß der alte Ormuzd zu dem guten Gott gemacht worden ist, während er eigentlich eine luziferische Macht ist, eine Lichtmacht. Dadurch allerdings hat man die Genugtuung haben können, daß man wiederum den Luzifer so schlecht wie möglich machen konnte; weil einem der Luzifername nicht gepaßt hat für den Ormuzd, hat man den Luzifer auf den Ahriman hingeleitet, hat einen Mischmasch gemacht, der noch bei Goethe in seiner Mephistophelesfigur nachwirkt, indem sich da ja auch Luzifer und Ahriman miteinander vermischen, wie ich ausdrücklich in meinem Büchelchen «Goethes Geistesart» gezeigt habe. Es ist in der Tat die europäische Menschheit, die Menschheit der gegenwärtigen Zivilisation in eine große Verwirrung hineingekommen, und diese Verwirrung geht schließlich durch alles Denken. Sie wird nur wettgemacht dadurch, daß man aus der Dualität wieder in die Trinität hineinführt, denn alles Duale führt zuletzt in etwas, in dem der Mensch nicht leben kann, das er als eine Polarität anschauen muß, in der er den Ausgleich nun wirklich finden kann: Christus ist da zum Ausgleich des Luzifer und Ahriman, zum Ausgleich von Ormuzd und Ahriman und so weiter.

Das ist das Thema, das ich einmal anschlagen wollte und das wir dann in den nächsten Tagen in verschiedenen Verzweigungen weiterführen wollen.