The Origin and Development of Eurythmy

1918–1920

GA 277b

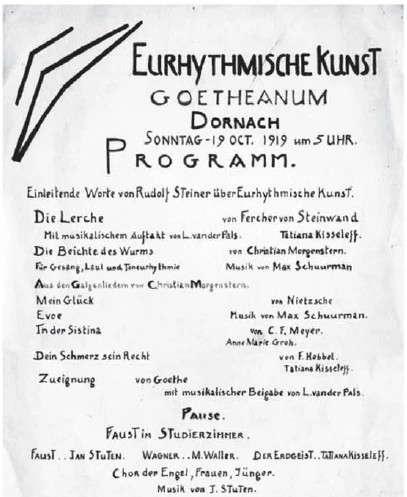

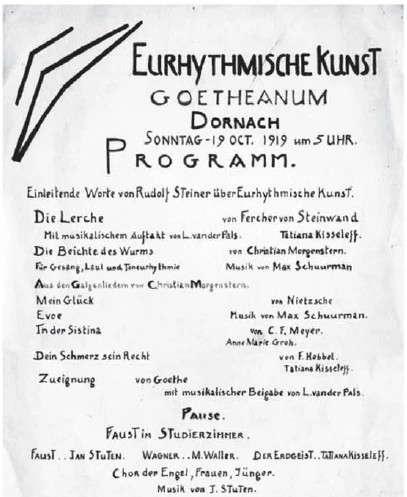

19 October 1919, Dornach

Translated by Steiner Online Library

26. Eurythmy Performance

Dear attendees!

The art of eurythmy, of which we are once again presenting a small sample to you today, is something that we ask you to receive in such a way that what we are able to offer is a beginning, an attempt that must lead in the future to what we actually envision as an ideal for the renewal of a certain field of art.

It is not based on the opinion that we want to present something equal to other, similar art forms, which are actually only seemingly similar art forms – dance arts and the like. What we call the eurythmic art here has been fully thought out, or perhaps I should say felt and sensed out of the Goethean world view. Indeed, when one speaks of the Goethean worldview in such a context, one must not think in a scholastic way of the Goethe who died in Weimar in 1832, but of that which lived and lives on as a spirit in Goethe and can be taken up anew by each generation.

It is an artistically defined area, an artistic area that is to be developed out of Goethe's world view as a eurythmic art. I do not wish to theorize, but I would like to say a few words about the sources of this eurythmic art.

Particularly when such an art form first appears in cultural development, it is important to realize that - especially in the Goethean sense, it is intended that way - what we enjoy artistically, aesthetically, is actually there in terms of the mysterious depths of things, that we also try to reveal this through our knowledge. Goethe had the peculiarity that for him art and science were not strictly separate fields. It is a very characteristic expression of Goethe's when he says: one should not actually speak of the idea of truth, of the idea of beauty, of the idea of goodness; for Goethe thought that the idea is one and everything, and it reveals itself sometimes as the goodness of man, sometimes as beauty, sometimes as truth. In saying this, Goethe had in mind something much more alive and spiritual than the abstract idea that many people today have in mind. He had in mind the idea of what is alive and animates nature itself, and what man in turn finds in himself if he only descends deep enough into the depths of his own being.

But we must enter into that which is most significant and characteristic of Goethe's world view if we want to see through what is actually meant here with eurythmy. The essence of Goethe's great view of nature, which is also an artistic view because it reveals itself artistically, is something that has not yet been sufficiently appreciated. Our science is basically a science of the dead, and we strive more and more, if we want to be true natural scientists, to understand the living as a dead thing, to think of the living as composed of the dead. Goethe wanted to look at the living directly. He called this looking at the living directly his metamorphosis doctrine.

Once this doctrine of metamorphosis has been extended to cover the entire field of the human world view, something powerful will emerge from this expansion of our view of nature, from the transformation of all human views of nature and the world. It may look primitive and theoretical to explain the simple basic principle of Goethe's world view, which he advocates in his doctrine of metamorphosis. But when it is fully developed, it is something great and powerful that leads us deep into the essence of things and also of man.

Goethe imagines that in every single plant organ, namely in every single plant leaf, be it a green leaf or a colored petal, a whole plant should be contained in a simple way. In turn, Goethe imagined that the whole plant, however complicated it grows, is just a transformed leaf. Each individual plant leaf can become a whole plant, and the whole plant, each individual organ, can in turn become a plant. And this is how Goethe imagined all living things, especially the living human organism.

But Goethe's observations were limited to the form. This was due to the time in which he lived. By translating Goethe's observations into artistic expression through our eurythmy, we do not want to stop at the forms, but move on to human activity. And here it becomes possible, with a certain intuitive higher perception, with a real seeing, to bring to mind in a different way what one hears from one's fellow human beings through the sense of hearing as one's fellow human being speaks or sings. In particular, by shaping language in a song-like way, that is, in a musical or poetic way.

In our daily lives, we direct our attention to what we can hear, to the activity of a single organ, the larynx and its neighboring organs. But he who, with a higher, supersensible gaze, looks through what happens in man as it reveals itself through a single organ, the larynx and its neighboring organs, can also , just as Goethe saw the individual leaf in the whole plant, so the one who has the gift of seeing can see the fine movements that are only potential in the larynx and its neighboring organs as movements of the whole human organism. And so what is presented to you here on the stage is, in essence, what language is, language made visible. What otherwise takes place invisibly in the human larynx is revealed here from the human organism as a whole, from all its limbs.

In this way we can create an art that can go hand in hand with the musical art. What is happening on stage will be accompanied by the person himself, who is like a large, living larynx, accompanied by music on the one hand, and on the other hand by the recitation.

However, it then becomes necessary, especially when what the whole person presents as a visible language is accompanied by recitation and by artful poetic language, to return to the good old forms of the art of recitation. The art of recitation today has basically gone astray. As much as people today dislike hearing it, it still has to be said. The art of recitation today has become more prosaic. What lies in the content of a poem is expressed through the art of recitation. This was not the case with the art of recitation in earlier times. The further back we go, the more the poetic artist was aware that rhythm, beat, the form of speech, the formal aspects, are the main thing.

I need only remind you that when Schiller set about a poem, he did not first feel the content of the words of the poem in himself, but something like a melody, an indefinite melody, something musical. This, which lies in the language, apart from the thought, the content of the image or the word, is actually the most important and significant thing artistically. This is what must also be particularly expressed in the art of recitation. Goethe, when he rehearsed his “Iphigenic”, even a drama with his actors, rehearsed it with the baton in his hand, seeing everywhere less what the word content is. This is basically only the prosaic ladder by which the actual poetic art climbs up. He looked at the poetic power of creation, at the formal.

In our art of recitation, which accompanies the eurythmic, you will see that essentially there is an inner rhythm in inner harmony of movement. What is really recitation art must also be expressed in recitation. Now, if you take the word as it is artistically designed, or even as a word, it is expressed in our visible language, which represents eurythmy, through what a person can initially reveal in his limbs as possible movements. But what we express, especially when we shape it musically or poetically, is imbued with inner warmth of soul, with joy and sorrow, with delight and pain. All this can also be presented in eurythmy.

In the movements that are less attached to the individual limbs of the human being, but which the whole person performs or which he performs in space or in the circumstances in which he enters when we give group performances, in addition to the other performances of the groups, in these movements, in the more spatial movements, and in the temporal, that which shakes and vibrates through our speech, our audible speech, as soul warmth, as desire and suffering, as joy and pain, as enthusiasm and so on, is then expressed. But there is nothing arbitrary about it. And this is precisely how our eurythmy differs from certain neighboring arts, which could easily be confused with it: everything is always lawful. Not a momentary gesture is taken to express anything in the soul. Just as music itself consists of a lawful succession of notes in its melodies, so eurythmy consists of a succession of movements. If two people or groups of people perform the same thing in eurythmy, it is just as if two pianists perform the same Beethoven sonata. Individual expression plays no greater a role in eurythmy than it does, for example, when playing a single note or a piece of music.

If you still see in our beginnings, in our first attempts, pantomime and mime, then this is still an imperfection that will also be overcome in the future. For it is precisely the pantomime, the facial expression, the gesture of the moment, that which otherwise inspires the art of dance, that is just as little included in our art as musical sound painting is included in real music. For us, it is not about somehow expressing moments through a gesture, through facial expressions, but rather about revealing these outwardly in accordance with an inner law that is inherent in the human organism, and thus, in reality, to fulfill in a particular limited area that which Goethe so beautifully expressed when he said: “To whom nature reveals her secret, longs for her most worthy interpreter, art.” For, since the human being is the synthesis of the laws of the harmonies of the whole universe, it is possible to artistically represent, in fact, something - one can say: of the laws of the whole universe - that is inherent in the human organism. While our knowledge presents the concept before that which is the secret of the world, art should express the secrets of the world directly.

If I give an explanation of what is presented in eurythmy, it is only to point to the source; because it is self-evident that everything artistic must be felt directly in aesthetic contemplation and must reveal itself as sympathetic to the soul.

But with Goethe, in particular, you see, esteemed attendees, one has the feeling that the art of eurythmy can pass the test. We have tried to present certain scenes from the second part of Goethe's “Faust” in eurythmy, namely the earlier performances here. You may know how difficult the second part of Faust is to present on stage. Yes, you may also know how many people say that the second part of Goethe's Faust is a late effort that no longer contains the power that Goethe expressed in his art in the first part.

Those who speak thus are very much mistaken. In the second part of his Faust, Goethe did indeed reveal as art that which, after a mature life experience, had opened up to him as the sources of art. But when you represent in eurythmy that which enters completely into the forms, which no longer has anything to do with the content of prose but has become pure art, you arrive at the subtleties. But starting from that, we then came to the point of, I would say, going through the Goethean poems to see to what extent that which lived artistically in Goethe's soul can be expressed through the special art of eurythmy, that is, through a visible language. And more and more it turns out that in the moment when Goethe's artistic thinking passes over into the supersensible, into that which does not live in ordinary outer life, that then the eurythmic art enters into its full right.

Of course, it is a daring statement to say today that Goethe's artistic thinking was such that, where he rises above the sphere of the everyday, one feels the necessity to move on to something that also goes beyond ordinary artistic representation and into eurythmic representation. But perhaps one can say something like this when one has gradually, over a long period of time, worked one's way up to that Goethean insight, which I believe is necessary, and which also takes Goethe seriously. When a lot of people, out of philistinism – Vischer and other people were, after all, also German aesthetes in a certain sense – when certain people feel they have to reject what Goethe created later – it's so hard to to grasp what one does not immediately understand, to struggle to understand, one much prefers to blame the poet for presenting it in such an incomprehensible way.

Goethe once made a harsh statement about people who also appeared during his lifetime, who, for example, appreciated his “Iphigenia” and his “Natural Daughter” less than, say, we might say, those parts in the first part of Faust, which ultimately welled up from his soul in an elemental way and are less artistic than what Goethe first achieved as an art form in the course of a long life. Goethe was angry with those who valued what he produced in his youth – including the parts of Faust, for example – more highly than what he later produced after he had developed a more mature view of art. It was this kind of anger that led to Goethe's remark, found in his estate, where he says in reference to the audience that no longer understood him:

They praise my Faust

And what else

In my works roars

In their favor.

The old Mick and Mack,

That pleases them very much,

[It means] the pack of ragamuffins

One would no longer be.

I am convinced, my dear attendees, that Goethe would express himself in a similar way about the understanding of Goethe, the presumed understanding of Goethe, that is spreading today.

But precisely when one encounters what Goethe has achieved, then one also feels the necessity to advance to new forms of art in order to express what Goethe presented in his early works.

Today, after the break, we are dealing with the beginning of the first part of Goethe's “Faust”, which is an early work. But we will try to do just those parts where what is otherwise ordinary life is led up into a higher sphere - where the human soul rises to a higher, supersensible one - [we will try to do that] just in the first part of “Faust” by means of eurythmy, so that one can get a sense of how the human being in his physical, sensual, earthly existence is connected to a higher existence.

In this way, we would like to use eurythmy to bring to revelation everything in the human being that lies deeply hidden as the actual secret of the world. But you will only do justice to this eurythmic art if you see it, as we are already able to offer it today, only as a beginning, as a weak attempt at what is to come. We are our own harshest critics and we know what is still lacking. But we believe that if our contemporaries show interest and attention to what is being attempted, it will be possible to bring this beginning to ever greater and greater perfection.

In short, we are convinced that the art form that we are in the process of creating in eurythmy will perhaps be developed further by ourselves, albeit weakly, but by others it will be developed more and more and that it will then be recognized as a fully-fledged art form alongside other fully-fledged art forms.

Programm zur Aufführung,

Meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden!

Die eurythmische Kunst, von der wir Ihnen eine kleine Probe heute wiederum vorzuführen uns erlauben, bitte ich Sie durchaus so aufzunehmen, dass zunächst dasjenige, was wir darbieten können, ein Anfang ist, ein Versuch, der erst in der Zukunft zu dem wird führen müssen, was wir uns eigentlich als ein Ideal einer Erneuerung eines gewissen Kunstgebietes denken.

Es ist nicht dabei die Meinung zugrunde liegend, dass wir neben anderen, ähnlichen Kunstformen, die eigentlich nur scheinbar ähnliche Kunstformen sind - Tanzkünste und dergleichen - etwas mit ihnen Ebenbürtiges hinstellen wollen. Dasjenige, was wir hier als eurythmische Kunst bezeichnen, das ist ganz herausgedacht, vielleicht müsste ich besser sagen herausernpfunden und herausgefühlt aus der Goethe’schen Weltanschauung. Allerdings, wenn man in solchem Zusammenhange spricht von der Goethe’schen Weltanschauung, so muss man nicht in gelehrtenhafter Weise an den Goethe denken, der 1832 in Weimar gestorben ist, sondern an dasjenige, was als Geist in Goethe lebte und fortlebt und sich fortentwickelt und von jeder Generation neu aufgenommen werden kann.

Es ist ein künstlerisch umgrenztes Gebiet, ein künstlerisches Gebiet, das aus der Goethe’schen Weltanschauung heraus als eurythmische Kunst entwickelt werden soll. Ich möchte nicht theoretisieren, aber ich möchte doch mit einigen Worten vorausschicken, was die Quellen dieser eurythmischen Kunst sind.

Man muss sich, namentlich wenn eine solche Kunstform zuerst in der Kulturentwicklung auftritt, durchaus klar machen, dass - gerade im Goethe’schen Sinne ist es gedacht so —, dass dasjenige, was wir künstlerisch, ästhetisch genießen, [was] eigentlich in Bezug auf geheimnisvolle Tiefen in den Dingen ist, dass wir uns [das] auch durch unsere Erkenntnis zu offenbaren versuchen. Goethe hatte das Eigentümliche, dass für ihn Kunst und Wissenschaft nicht streng voneinander geschiedene Gebiete waren. Ein sehr charakteristischer Ausdruck von Goethe ist der, indem er sagt: Man sollte eigentlich nicht sprechen von der Idee der Wahrheit, von der Idee der Schönheit, von der Idee der Güte; denn Goethe meinte, die Idee sei Eins und Alles, und sie offenbart sich einmal als Güte des Menschen, einmal als Schönheit, einmal als Wahrheit. Dabei hatte Goethe allerdings im Auge etwas viel Lebendigeres, Geistigeres, als das Abstrakte, das viele Menschen sich heute unter Idee vorstellen. Er hatte dasjenige unter Idee im Auge, was lebendig die Natur selbst beseelt, und was der Mensch wiederum in sich findet, wenn er nur tief genug in die Schächte seines eigenen Wesens hinuntersteigt.

Aber man muss schon eingehen auf dasjenige, was gerade das Bedeutungsvolle und Charakteristische der Goethe’schen Weltanschauung ist, wenn man durchschauen will, was eigentlich hier mit der Eurythmie gemeint ist. Das Wesentliche in Goethes großer Naturanschauung, die eben zugleich, indem sie künstlerisch sich offenbart, Kunstanschauung ist, das Wesentliche ist etwas, das noch lang nicht genügend gewürdigt ist. Unsere Wissenschaft ist im Grunde genommen eine Wissenschaft vom Toten, und wir streben immer mehr und mehr, wenn wir rechte Naturwissenschaftler sein wollen, danach, auch das Lebendige als ein Totes zu begreifen, das Lebendige als aus dem Toten Zusammengeserztes uns zu denken. Goethe wollte das Lebendige unmittelbar anschauen. Er nannte dieses Anschauen des unmittelbar Lebendigen seine Metamorphosenlehre.

Wird einmal diese Metamorphosenlehre ausgedehnt sein über das ganze Gebiet der menschlichen Weltanschauung, so wird aus diesem Ausgedehntsein etwas Gewaltiges an der Naturanschauung, an Umwandlung aller menschlichen Natur- und Weltanschauung hervorgehen. Es sieht primitiv, theoretisch aus, wenn man das einfache Grundprinzip Goethe’scher Weltanschauung klarlegt, das er in seiner Metamorphosenlehre vertritt. Allein - ausgestaltet ist es etwas Großes, etwas Gewaltiges, das uns tief hineinführt in das Wesen der Dinge und auch des Menschen.

Goethe stellt sich vor, dass in jedem einzelnen Pflanzenorgan, namentlich in jedem einzelnen Pflanzenblatt, sei es grünes Laubblatt, sei es farbiges Blütenblatt, in einfacher Weise eine ganze Pflanze enthalten [sein] soll. Wiederum stellte sich Goethe vor, dass die ganze Pflanze, wenn sie noch so kompliziert sich auswächst, nur ein umgestaltetes Blatt ist. Jedes einzelne unter den Pflanzenblättern kann eine ganzc Pflanze werden, die ganze Pflanze, jedes einzelne Organ wird wiederum eine Pflanze. Und so stellte sich Goethe alles Lebendige vor, vor allem auch den lebendigen menschlichen Organismus.

Aber Goethe ist allerdings seinerzeit bei der Anschauung der Form stehengeblieben. Das lag in seiner Zeit. Wir wollen, indem wir Goethes Anschauung ins Künstlerische hier umsetzen durch unsere Eurythmie, nicht bei den Formen stehen bleiben, sondern übergehen zur menschlichen Tätigkeit. Und da zeigt es sich denn als möglich, dass man mit einer gewissen intuitiven höheren Anschauung, mit einem wirklichen Schauen, dasjenige noch in anderer Art sich vor die Seele bringen kann, was der Mensch an seinen Mitmenschen hört, durch den Sinn des Hörens wahrnimmt, indem der Mitmensch spricht oder singt. Namentlich, indem er die Sprache gesanglich, also musikalisch oder dichterisch auch gestaltet.

Im gewöhnlichen Leben lenken [wir unsere] Aufmerksamkeit auf dasjenige, was wir hören können, auf dasjenige, was die Tätigkeit eines einzelnen Organes ist, den Kehlkopf und seine Nachbarorgane. Derjenige, der nun aber mit einem höheren Schauen, mit einem übersinnlichen Anschauen dasjenige durchblickt, was im Menschen geschieht als sich offenbarend durch ein einzelnes Organ, durch den Kehlkopf und seine Nachbarorgane, der kann auch, so wie Goethe das einzelne Blatt in der ganzen Pflanze sah, so kann der Schauende sehen dasjenige, was im Kehlkopf und seinen Nachbarorganen an feinen Bewegungen nur veranlagt ist, als Bewegungen des ganzen menschlichen Organismus. Und so wird Ihnen hier auf der Bühne vorgeführt werden im Grunde genommen dasjenige, was eine Sprache ist, eine sichtbar gewordene Sprache. Was sonst im menschlichen Kehlkopf unsichtbar vor sich geht, wird aus dem Gesamtorganismus des Menschen, aus allen seinen Gliedern hier geoffenbart.

So können wir eine Kunst schaffen, welche parallel gehen kann erstens der musikalischen Kunst. Sie werden daher dasjenige, was auf der Bühne vorgeht durch den Menschen selbst, der gleichsam ein großer, lebendig gewordener Kehlkopf ist, begleitet finden durch das Musikalische einerseits, und auf der anderen Seite begleitet finden durch die Rezitation.

Es wird dann aber notwendig, gerade wenn man durch die Rezitation, durch kunstvolle dichterische Sprache begleitet dasjenige, was der ganze Mensch als eine sichtbare Sprache darstellt, es wird dann notwendig, in der Rezitationskunst wiederum zu den guten alten Formen dieser Kunst zurückzukehren. Die Rezitationskunst der Gegenwart ist im Grunde genommen auf einem Abwege. So ungerne es die Menschen gegenwärtig hören, muss man es doch sagen. Die Rezitationskunst der Gegenwart ist mehr prosaisch geworden. Man lässt dasjenige, was dem Wortinhalte nach in einer Dichtung liegt, durch die Rezitationskunst zum Ausdruck bringen. Das war nicht so bei der Rezitationskunst früherer Zeiten. Je weiter wir zurückgehen, desto mehr war sich auch der dichterische Künstler bewusst, dass Rhythmus, Takt, dass die Form der Sprachgestaltung, das Formelle, dass das die Hauptsache ist.

Ich brauche nur daran zu erinnern, dass Schiller, wenn er an ein Gedicht ging, nicht zunächst den Wortinhalt des Gedichtes in sich empfand, sondern etwas wie eine Melodie, wie eine unbestimmte Melodie, also etwas Musikalisches empfand. Dies, was in der Sprache liegt abgesehen von dem Gedanken, Vorstellungs- oder Wortinhalt, das ist eigentlich das künstlerisch Hauptsächlichste, das künstlerisch Bedeutsame. Das ist dasjenige, was auch in der Rezitationskunst besonders zum Ausdrucke kommen muss. Goethe hat, wenn er seine «Iphigenic», also sogar ein Drama mit seinen Schauspielern einstudierte, sie mit dem Taktstock in der Hand einstudiert, überall weniger sehend auf dasjenige, was der Wortinhalt ist. Das ist im Grunde genommen nur die prosaische Leiter, an der sich die eigentliche dichterische Kunst hinaufrankt. Er hat gesehen auf die dichterische Gestaltungskraft, auf das Formelle.

In unserer Rezitationskunst, welche das Eurythmische begleitet, werden Sie sehen, dass im Wesentlichen ein innerer Rhythmus in innerer Bewegungsharmonie besteht. Da muss auch rezitierend dasjenige zum Ausdruck kommen, was wirklich Rezitationskunst ist. Nun, wenn man das Wort nimmt, wie es künstlerisch gestaltet ist, oder überhaupt als Wort, so wird das in unserer sichtbaren Sprache, welche die Eurythmie darstellt, ausgedrückt durch dasjenige, was zunächst der Mensch in seinen Gliedern als Bewegungsmöglichkeiten zur Offenbarung bringen kann. Aber dasjenige, was wir aussprechen, insbesondere, wenn wir es musikalisch, wenn wir es dichterisch gestalten, es ist durchzogen von innerer Seelenwärme, von Lust und Leid, von Freude und Schmerz. Das alles ist auch möglich eurythmisch darzustellen.

In den Bewegungen, die weniger an den einzelnen Gliedern des Menschen haften, sondern die mehr der ganze Mensch ausführt oder die er ausführt im Raume oder in den Verhältnissen, in die er tritt, wenn wir Gruppendarstellungen geben, zu den anderen Darstellungen der Gruppen, in diesen Bewegungen, also in den mehr räumlichen Bewegungen, im Zeitlichen drückt sich dann dasjenige aus, was unsere Sprache, unsere hörbare Sprache durchbebt, durchvibriert als Seelenwärme, Lust und Leid, Freude und Schmerz, als Enthusiasmus und so weiter, aber es ist nichts Willkürliches. Und damit unterscheidet sich unsere Eurythmie gerade von gewissen Nachbarkünsten, die man leicht mit ihr verwechseln könnte: Alles ist immer gesetzmäßig. Nicht ist eine Augenblicksgebärde genommen, um irgendetwas seelisch auszudrücken. Geradeso, wie die Musik selber in ihren Melodien besteht in einer gesetzmäßigen Aufeinanderfolge der Töne, so besteht Eurythmie in einer Aufeinanderfolge der Bewegungen. Wenn zwei Menschen oder Menschengruppen dasselbe eurythmisch darstellen, so ist das geradeso, wie wenn zwei Klavierspieler ein und dieselbe Beethovensonate darstellen. Individuelles spielt in keinem anderen Sinne eine Rolle beim Eurythmischen, als zum Beispiel bei der musikalischen Wiedergabe irgendeines Tones oder Tonstücks.

Wenn Sie noch sehen in unseren Anfängen, in unseren ersten Versuchen Pantomimisches, Mimisches, so ist das ganz und gar noch eine Unvollkommenheit, die auch eben in der Zukunft abgestreift werden wird. Denn gerade das Pantomimische, das Mimische, die Augenblicksgeste, dasjenige, was sonst die Tanzkunst beseelt, das ist bei uns ebenso wenig enthalten, wie in wirklicher Musik Tonmalerei enthalten ist. Bei uns kommt es nicht darauf an, Augenblicke durch eine Geste, durch Mimik irgendwie auszudrücken, sondern auf eine innere Gesetzmäßigkeit, die im menschlichen Organismus veranlagt ist, diese äußerlich zu offenbaren und damit in Wirklichkeit zu erfüllen auf einem bestimmten beschränkten Gebiete dasjenige, das Goethe so schön ausdrückte, indem er sagte: Wem die Natur ihr offenbares Geheimnis enthüllt, der sehnt sich nach ihrer würdigsten Auslegerin, der Kunst. Denn, da der Mensch die Zusammenfassung der Gesetzmäßigkeit der Harmonien des ganzen Weltenalls ist, so kann man insbesondere dasjenige, was im menschlichen Organismus veranlagt ist, künstlerisch darstellen, tatsächlich etwas - man kann sagen: von der Gesetzmäßigkeit des ganzen Weltenalls. Während unsere Erkenntnis den Begriff hinstellt vor dasjenige, was Weltengeheimnis ist, soll da die Kunst unmittelbar ausdrücken die Weltengeheimnisse.

Wenn ich eine Erklärung für dasjenige gebe, was eurythmisch dargestellt wird, so ist es nur, um auf die Quelle hinzuweisen; denn selbstverständlich ist es, dass alles Künstlerische unmittelbar in ästhetischer Anschauung empfunden werden muss und sich als sympathisch der Seele offenbaren muss.

Gerade aber bei Goethe, sehen Sie, sehr verehrte Anwesende, hat man das Gefühl, dass die eurythmische Kunst ihre Probe bestehen kann. Wir haben versucht, namentlich gewisse Szenen - die früheren Vorstellungen hier - aus dem zweiten Teil des Goethe’schen «Faust» eurythmisch darzustellen. Sie werden ja vielleicht wissen, wie schwierig gerade der zweite Teil des «Faust» sich bei Bühnendarstellungen machte. Ja, Sie werden auch wissen, wie viele Leute sagen: Dieser zweite Teil des Goethe’schen «Faust» - das ist ein Machwerk des Alters, der enthält nicht mehr die Kraft, die Goethe in seinem ersten Teil in seiner Kunst zum Ausdruck gebracht hat.

Die Leute, die so sprechen, haben sehr Unrecht. Goethe hat allerdings in seinem «Faust» im zweiten Teile dasjenige als Kunst zur Offenbarung gebracht, was sich ihm nach einer reifen Lebenserfahrung als die Quellen der Kunst erschlossen haben. Gerade aber, wenn man dasjenige, was nun ganz und gar in die Formen hineingeht, was gewissermaßen nichts mehr zu tun hat mit dem Prosainhalt, sondern ganz Kunst geworden ist, wenn man das eurythmisch darstellt, dann kommt man auf die Feinheiten. Davon aber ausgehend sind wir dann dazu gekommen, überhaupt, ich möchte sagen die Goethe’schen Dichtungen zu durchmessen daraufhin, inwiefern dasjenige, was in Goethes Seele künstlerisch lebte, durch die besondere eurythmische Kunst, also durch eine sichtbare Sprache, zum Ausdruck gebracht werden kann. Und immer mehr stellt es sich uns doch so heraus, dass in dem Augenblicke, wo das Goethe’sche Künstlerische übergeht in das Übersinnliche, in dasjenige, was nicht im äußeren gewöhnlichen Leben lebt, dass dann die eurythmische Kunst in ihr volles Recht eintritt.

Gewiss ist es heute ein Wagnis zu sagen: Goethe hat formkünstlerisch so gedacht, dass man die Notwendigkeit empfindet, da, wo er sich über die Sphäre des Alltäglichen erhebt, zu so etwas überzugehen, was auch aus dem gewöhnlichen künstlerischen Darstellen hinausgeht, in die eurythmische Darstellung übergeht. Aber man darf vielleicht so etwas [aussprechen], wenn man sich allmählich, nach längerer Zeit hinaufgerankt hat zu jener Goethe’schen Erkenntnis, von der ich glaube, dass sie nötig ist, die es dann auch ernst nimmt mit Goethe. Wenn zahlreiche Menschen glauben aus einer philiströsen Art heraus - Vischer und andere Leute waren ja in gewisser Beziehung auch deutsche Ästhetiker -, wenn gewisse Leute ablehnen zu müssen glauben dasjenige, was Goethe später geschaffen hat — man lässt sich ja so schwer darauf ein, dasjenige, was man nicht gleich versteht, so aufzufassen, dass man sich erst zum Verständnisse durchzuringen hat, man liebt es vielmehr, dem Dichter die Schuld zu geben, dass er so unverständlich darstellt.

Goethe hat einmal einen herben Ausspruch getan über die Leute, die auch zu seinen Lebzeiten aufgetreten sind, die zum Beispiel seine «Iphigenie», seine «Natürliche Tochter», weniger geschätzt haben als, sagen wir diejenigen Partien im ersten Teil des «Faust», die schließlich elementar hervorgequollen sind aus seiner Seele und weniger künstlerisch sind als dasjenige, was sich Goethe als Kunstform erst errungen hat im Laufe eines langen Lebens. Goethe war erbost über diejenigen, die das höher schätzten, was er in seiner Jugend hervorgebracht hat — auch als «Faust»-Partien zum Beispiel -, gegenüber dem, [was] er später, nachdem er zu einer abgeklärten Kunstanschauung übergegangen war, [hervorbrachte]. Aus einer solchen Erbostheit ging ja Goethes Ausspruch hervor, den man in seinem Nachlasse fand, wo er sagt in Bezug auf das Publikum, das ihn nicht mehr verstand:

Da loben sie meinen Faust

Und was noch sunsten

In meinen Werken braust

Zu ihren Gunsten.

Das alte Mick und Mack,

Das freut sie sehr,

[Es meint] das Lumpenpack

Man wär’s nicht mehr.

Ich bin überzeugt davon, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, dass Goethe sich in einer solchen Weise ungefähr auch dem Goethe Verständnis, dem angemaßten Goethe-Verständnis, das sich heute breit macht, aussprechen würde.

Gerade aber dann, wenn einem das entgegentritt, was Goethe sich errungen hat, dann empfindet man auch die Notwendigkeit, zu neuen Kunstformen vorzuschreiten, um das zum Ausdruck zu bringen, was Goethe in seinen Erstlingswerken hingestellt hat.

Allerdings haben wir es heute nach der Pause mit dem Anfange des ersten Teils von Goethes «Faust» mit einem Erstlingswerk zu tun. Aber wir wollen versuchen, gerade diejenigen Partien, wo hinaufgeführt dasjenige ist, was sich sonst als alltägliches Leben abspielt, in eine höhere Sphäre - wo die menschliche Seele sich erhebt zu einem Höheren, Übersinnlichen -, [wir wollen versuchen, dass] das gerade auch im ersten Teil des «Faust» in einem Anfange durch eurythmische Kunst in diejenige Art des Offenbarens des Menschen- und Weltenwesens hinaufgetragen wird, durch die man eine Empfindung davon haben kann, wie der Mensch in seinem physisch-sinnlichen, irdischen Dasein zusammenhängt mit einem höheren Dasein.

So möchten wir eben durch die Eurythmie alles dasjenige vom Menschen zur Offenbarung bringen, was in dem Menschen als das eigentliche Weltengeheimnis tief verborgen liegt. Aber Sie werden dieser eurythmischen Kunst nur gerecht werden, wenn Sie sie, so wie wir sie heute schon bieten können, nur als einen Anfang, als einen schwachen Versuch desjenigen, was werden soll, ansehen. Wir sind selbst die strengsten Kritiker, und wissen, was an ihr noch unvollkommen ist. Aber wir glauben, dass, wenn unsere Zeitgenossen dem, was erst versucht wird, Interesse entgegenbringen, Aufmerksamkeit entgegenbringen, so wird es doch dann möglich sein, diesen Anfang zu immer größerer und größerer Vollkommenheit zu bringen.

Kurz, wir sind davon überzeugt, dass die Kunstform, an deren Anfang wir damit stehen in der Eurythmie, dass die vielleicht noch von uns selbst - aber wahrscheinlich schwach -, aber von anderen immer weiter und weiter ausgebildet werden wird und dass sie sich dann als eine vollberechtigte Kunstform neben andere Kunstformen, die vollberechtigt sind, wird hinstellen lassen.