The Origin and Development of Eurythmy

1918–1920

GA 277b

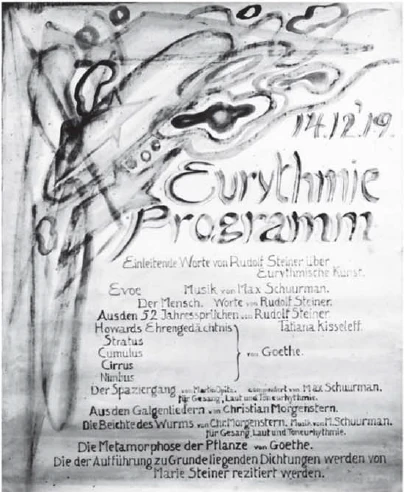

14 December 1919, Dornach

Translated by Steiner Online Library

37. Eurythmy Performance

Public eurythmy performance in the presence of English friends

Dear attendees,

We would like to take the liberty of presenting a sample of what we call the eurythmic arts here. However, the art we are able to practice here is only just beginning. It is the attempt at the beginning of a new art. And so, just as everything that is striven for here in connection with this building, which is intended to represent our efforts in a certain sense, how everything here wants to tie in with what I would like to call Goetheanism, so this eurythmic art also wants to tie in with Goethe's artistic and world-view attitude. Just by saying this, I ask not to be misunderstood. It is not, so to speak, that which is to be linked to what has already emerged through Goethe, who died in 1832, but rather Goetheanism, which has been thrown into the evolution of humanity like a seed and which can produce the most diverse blossoms and fruits. We are not talking here about the Goethe of 1832, we are talking about the Goethe of 1919, about an evolved Goetheanism.

And an attempt has been made to educate this eurythmic art from the same meaningful, deep sources from which Goethe drew his worldview and his artistic endeavors, in line with the progress that the human spirit has made since then. And it is not to explain this art that I would like to speak these introductory words, because that which is art must explain itself, must reveal everything that is in it in the direct gaze for the aesthetic impression. But I would like to speak to you about the sources of what we call eurythmic art here. This eurythmic art makes use of the whole human being as a means of expression. It attempts to express all the possibilities of movement that are inherent in the human organism.

On the stage here before you, you will see people moving, groups of people moving. What is it that these people are meant to present? It is also a language, an inaudible, mute language. But it is not just a comparison that I use when I say that eurythmy should be a language, but it is the expression of a reality. When people speak in such a way that our spoken words become audible, then, spiritually speaking, two elements of the human being flow together in what we speak: from one side - I would say from the head side - the element of thought; and from the whole human being, the will element encounters this element of thought, which works through its organs – today this can also be proven physiologically. In every single word we speak, there is a revelation of the confluence of the element of thought with the element of will.

Now, when we listen to a spoken word, we first turn our attention through the ear to the tone, the sound, the sound context, and so on. But behind what reaches us as sound, as tone, as tone and sound relationships, in the vocal, in the musical and in the literal, lie the underlying possibilities of movement of the larynx and its neighboring organs, the tongue, the palate and so on. We do not pay attention to these movements. We simply hear the sound. Through a certain kind of looking – in the Goethean sense, one could speak of a sensual-supersensory looking – the one who enables himself to do so can perceive which movements, in particular which movement tendencies, underlie the spoken word. These movement tendencies of the larynx and its neighboring organs are to be grasped.

And from this knowledge of what really happens in the human being, through movements, when he speaks, the art of eurythmy has arisen from observation of this. In the training of this eurythmy, too, we have proceeded, if I may say so, in a Goethean way. You are familiar with – I do not want to theorize, but I just want to briefly mention an important principle of knowledge and art of Goethe – you are familiar with what is called the Goethean theory of metamorphosis. It has not yet been sufficiently appreciated today, because once its foundations are recognized, it will be the gateway to a meaningful world view that leads into the living. Goethe's view, if I am to express myself in popular terms, is that in every living thing, for example in plants, a single organ, the green leaf, is the simpler expression, the simpler revelation of the whole plant. And again, the whole plant is only the complicated expression of the individual leaf. And what Goethe applied only to form can be applied to the movements that find expression in an organism.

And it becomes particularly meaningful when this view is applied in such a way that one artistically brings out of the human being what is present in the whole human being in the way of movement. Something very interesting comes to light here. It turns out that the movements that can be perceived through the characterized sensory-supersensory vision as underlying our language can be transferred to the whole person. Just as the whole plant is morphologically, formally, a complicated development of the individual leaf, so can the whole person be moved in his limbs so that he becomes a living larynx. Then the whole human being performs that which otherwise remains invisible and unnoticed to us when we listen to speech.

On the one hand, you create a tool for an art. You create the whole human being as a tool for this eurythmic art. And since the same movements that the larynx and its neighboring organs make can be extracted from the whole human being, the whole human being becomes a visible expression of speech. When you consider that the human being, as he stands before us in his organization - in fact, you only have to look through him to see this - is a summary of all that is otherwise spread out in the whole universe that is accessible to us , then one recognizes that eurythmy uses as its instrument of expression the most complicated tool, the tool that contains the most secrets of the universe. By turning the whole human being into a larynx, one comes very close to what Goethe so beautifully characterized as his view of the relationship between man, nature and art, when he says: “When man is placed at the top of nature and feels himself to be this summit, he in turn produces a higher nature within himself, so that he finally elevates himself to the production of the work of art by combining measure, order, harmony and meaning.

But at the same time, something else is achieved. The essence of art lies in the fact that, by immersing ourselves in the work of art, we silence all understanding, all intellectual activity, everything that lives only in concepts and ideas. The more art contains ideas and concepts, the less it is art. If you bypass everything conceptual and imaginative and immerse the whole person in the revelation of nature's secrets, you come closer to excluding ideas, to the true weaving and reign of nature's secrets. Then this perception, this perception without ideas or concepts, and this immersion in things is precisely the artistic.

And working with such secrets of the universe, which cannot be grasped conceptually but only by immersing the whole human being in them, excluding the conceptual and the imaginative, can be achieved to the highest degree through eurythmy. For I have told you: in ordinary speech, two elements flow together, the thought element and the will element. By transferring the movement tendencies of the larynx and its neighboring organs to the whole human being, so that one creates a mute language through this whole human being, one excludes precisely the thought element and the will element, which is rooted in the whole human being. This is then expressed through the movements that you see on stage. And so, on the one hand, you will see in the individual representations something like the whole human being as a moving larynx; you will see groups of people; you will also see movements of the individual human being in space, and the relationships of movement between the individual members of the groups.

If we shape the art of eurythmy as I have described, it becomes quite natural for us to want to express the warmth of soul, the enthusiasm, the joy and suffering, the delight and pain, the uplift and so on that flows through our words. Everything that flows and permeates the speech element more from the heart, so to speak, is expressed through the movements of the individual in space and through the movements of the groups, through the relationships of the groups among themselves, while the actual speech element, that is, that which lies in the sound and in the sequence of sounds, is expressed by the whole human being moving his limbs.

But this is what distinguishes what we are attempting here with eurythmy from all neighboring arts. We certainly do not want to compete with these neighboring arts, with the various types of dance. We are well aware that they are, of course, more perfect in their way than our eurythmy, which is only at the beginning of its endeavors. But it is something completely different. These arts create a connection between the gesture of movement and the soul, which is, so to speak, an instantaneous connection. But everything that can be expressed in this way through pantomime, through momentary gestures, is not what we strive for in our eurythmy. Just as speech itself is thoroughly lawful, just as the musical is lawful, so there is also a strict inner lawfulness in what we strive for in eurythmy. If something pantomime-like or mimic-like still comes through, it is still an imperfection and will be discarded later when the eurythmic art becomes more and more perfect.

Therefore, there is nothing arbitrary about it. If two people or two groups of people in different places were to present one and the same thing in eurythmy, no greater leeway would be allowed for individual interpretation than is allowed when two pianists present one and the same Beethoven sonata according to their own interpretation. Everything arbitrary is excluded. It is a lawful, silent language. Therefore, today, when of course not everyone can be present at the eurythmic as such, this eurythmic can be accompanied on the one hand by the musical, which is, after all, the expression of the same, but can also be accompanied by the recitation.

And it is precisely in recitation that it becomes clear how art finds its way to art when combined with eurythmy. You can't recite as it is popular to recite today. Today, when reciting, the unartistic element of poetry is particularly favored. Today, when reciting, a great deal of attention is paid to the fact that the content of the prose is expressed through the recitation. And that is also what one loves. This is the unartistic element. One feels this unartistic element when one remembers, firstly, how certain types, I would like to say of primitive recitation, have been emphasized in primitive cultures. Those of us who are older could still experience this in the countryside; we could see how the storytellers, as they traveled around, accompanied their tales with gestures that were very natural, not in the sense as one would call it today, but which were actually very similar to our eurythmic gestures, accompanied with such gestures, often with the whole body moving around, what they presented in the recitative.

And after all, it is not the content of prose that is the main basis of real poetry, but rather the rhythmic, the formal, the formal, the rhythmic, the lawful in the succession of the audible. When writing his most significant poems, Schiller did not begin with the literal content in mind, but rather had something vaguely melodious in his soul, and it was only later, when he added the literal content to this vaguely melodious quality, that the literal content was added. The formative process that underlies all real poetry should be felt everywhere. Most of the things we call poetry today are not really poetry. So much is written today that, in fact, ninety-nine percent too much is written. But eurythmy could not be used to accompany the art of recitation, which is so popular today and which pays particular attention to the literal content of prose.

So here we are trying to go back to the truly artistic in the art of recitation as well. Goethe, with the baton still in his hand like a conductor, rehearsed his “Iphigenia”, a dramatic poem, with his actors, looking at what lies at the heart of the truly artistic. The formal elements of the prose, the literal content, are not the basis for the truly artistic expression. And so it is particularly the case that what is otherwise expressed in poetry through the word, can be represented in its will element through the eurythmic art. You will therefore hear recitations of poems, and you will see these poems presented on stage in the silent eurythmic language.

I believe that Goethe's poems in particular demonstrate the validity of this eurythmic art. Today we will show you, for example, eurythmy performances for Goethe's cloud poems. Goethe also applied his metamorphic view - more externalizing it, but thereby precisely translating it into art - to the transforming cloud formations stratus, cumulus, cirrus, nimbus. Goethe has illustrated in beautiful verses how these cloud formations transform into one another, an insight that came to him when he read the cloud observer Howard. He wrote a very beautiful poem “To Howard's Honorary Memory”, which we will also present to you today in eurythmy. But especially when one has such poems by Goethe, in which it is so important to follow a process in nature in poetry with such forms that the process in nature wells up and surges in the rhythm and shaping of language, then one can also follow the poetry with the forms of eurythmy. And that is why I believe that Goethe's Cloud Poems are particularly suitable for beautifully expressing how eurythmy can be found to be completely adequate for expressing what can also be expressed poetically.

Now there is a poem by Goethe in which Goethe himself has expressed the whole nature of his metamorphic thought, his metamorphic feeling, in the poem “The Metamorphosis of Plants”. The whole poem lives in the presentation of form observation. From line to line, we actually have the feeling that we must not cling to the abstract idea, but that we must show ourselves obedient with our whole soul to the forms that surge and swell in the poet's imagination. And that is why the eurythmic presentation can be fully adapted to this particular poem of Goethe's about metamorphosis. And for today's performance, we have also tried to cast this poem by Goethe about the metamorphosis of plants in eurythmic forms. Especially where the poetry itself becomes like an imprint of the secrets of nature, directly created by the soul, the artistic development of human feeling reveals itself on the one hand, on the other hand, the possibility of presenting this artistic element in the way it can be presented when the whole human being is used, as I have indicated, as a kind of musical-linguistic instrument. Thus we can indeed penetrate deeply into the secrets of nature if we seek these secrets in this formal language, which we strive to reveal in eurythmy.

I only ask you to consider everything that we can present today, everything that we can currently offer as a sample of our eurythmic art, as a beginning, perhaps as an attempt at a beginning. We are our own harshest critics, even in relation to what we can already do today. However, we are also convinced that if what is alive in the attempt at a new art is further developed, either by ourselves or probably by others – and there are many, many possibilities for development in this – then this eurythmic art will certainly be able to present itself as a fully-fledged art form alongside other fully-fledged art forms. As I said, we are being modest in what we can offer today, and I therefore ask you to also accept what we will present to you with indulgence as the beginning of a new art form.

Ansprache zur Eurythmie

Öffentliche Eurythmie-Aufführung in Anwesenheit englischer Freunde

Meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden!

Eine Probe von dem, was wir hier eurythmische Kunst nennen, möchten wir uns erlauben, Ihnen vorzuführen. Diese Kunst ist allerdings so, wie wir sie hier treiben können, erst im Anfange. Es ist der Versuch des Anfanges einer neuen Kunst. Und so wic alles dasjenige, was hier angestrebt wird im Zusammenhange mit diesem Bau, der unsere Bestrebungen in gewissem Sinne repräsentieren soll, wie alles hier anknüpfen will an das, was ich nennen möchte Goetheanismus, so will auch diese eurythmische Kunst anknüpfen an Goethe’sche Kunstgesinnung, Goethe’sche Weltanschauungsgesinnung. Allein, indem ich das ausspreche, bitte ich, mich nicht misszuverstehen. Nicht angeknüpft werden soll gewissermaßen an dasjenige, was durch den Goethe schon zum Vorschein gekommen ist, der 1832 gestorben ist, sondern betrachtet wird hier der Goetheanismus, [der] wie ein Keim hineingeworfen worden ist in die Evolution der Menschheit und der die mannigfaltigsten Blüten und Früchte treiben kann. Wir reden hier niemals von dem Goethe von 1832, wir reden hier von dem Goethe von 1919, von einem fortgebildeten Goetheanismus.

Und versucht ist worden, aus jenen bedeutungsvollen, tiefen Quellen, aus denen Goethe seine Weltanschauung, seine Kunstbestrebungen geschöpft hat, nun auch entsprechend den Fortschritten, die der menschliche Geist seither gemacht hat, auch diese eurythmische Kunst auszubilden. Und nicht um diese Kunst zu erklären, möchte ich diese Einleitungsworte sprechen, denn dasjenige, was Kunst ist, muss sich selbst erklären, muss im unmittelbaren Anblicke für den ästhetischen Eindruck alles dasjenige offenbaren, was in ihm ist. Aber über die Quellen dessen, was wir hier eurythmische Kunst nennen, möchte ich Ihnen sprechen. Diese eurythmische Kunst bedient sich als Ausdrucksmittel des ganzen Menschen. Es wird versucht, alle diejenigen Bewegungsmöglichkeiten, die im menschlichen Organismus veranlagt sind, zum Ausdrucke zu bringen.

Sie werden auf der Bühne hier vor sich bewegte Menschen, in Bewegung begriffene Menschengruppen sehen. Was ist dasjenige, was durch diese Menschen zur Darstellung kommen soll? Es ist auch eine Sprache, eine nicht hörbare, eine stumme Sprache. Aber es ist nicht bloß ein Vergleich, den ich gebrauche, wenn ich sage: Eurythmie soll sein eine Sprache, sondern es ist der Ausdruck einer Wirklichkeit. Wenn die Menschen so sprechen, dass unser Gesprochenes hörbar wird, so fließen zusammen, jetzt seelisch gesprochen, in dem, was wir sprechen, zwei Elemente des menschlichen Wesens: von der einen Seite her - ich möchte sagen von der Kopfseite her - das Gedankenelement; und von dem ganzen Menschen aus begegnet sich in der Sprache mit diesem Gedankenelement, das durch seine Organe wirkt- man kann das heute schon physiologisch auch nachweisen —, es begegnet sich mit diesem Gedankenelemente das Willenselement. In jedem einzelnen Worte, das wir hervorbringen, ist eine Offenbarung enthalten eines Zusammenflusses des Gedankenelementes mit dem Willenselement.

Nun, wenn wir dem gesprochenen Worte zuhören, wenden wir unsere Aufmerksamkeit zunächst durch das Ohr dem Ton, dem Laut, dem Lautzusammenhange und so weiter zu. Aber hinter dem, was da zu uns dringt als Laut, als Ton, als Ton- und Lautzusammenhang, in dem Gesanglichen, in dem Musikalischen und in dem Wörtlichen liegen zugrunde Bewegungsmöglichkeiten des Kehlkopfes und seiner Nachbarorgane, der Zunge, des Gaumens und so weiter. Diese Bewegungen, wir beachten sie nicht. Wir hören einfach den Ton. Durch ein gewisses Schauen - im Goethe’schen Sinne könnte man sprechen von einem sinnlich-übersinnlichen Schauen - kann derjenige, der sich dazu befähigt, wahrnehmen, welche Bewegungen, insbesondere welche Bewegungsanlagen, Bewegungstendenzen zugrunde liegen dem gesprochenen Worte. Diese Bewegungstendenzen des Kehlkopfes und seiner Nachbarorgane sind versucht aufzufassen.

Und aus der Erkenntnis desjenigen, was also wirklich im Menschen geschieht, durch Bewegungen geschieht, wenn er spricht, aus der Beobachtung dessen ist entstanden die Kunst der Eurythmie. Auch in der Ausbildung dieser Eurythmie ist [man] - wenn ich so sagen darf - goethisch zu Werke gegangen. Sie kennen - ich will nicht theoretisieren, aber ich will nur in Kurzem ein wichtiges Erkenntnis- und Kunstprinzip Goethes anführen -, Sie kennen dasjenige, was man die Goethe’sche Metamorphosenlehre nennt. Sie ist heute noch nicht genügend gewürdigt, denn wenn sie einmal in ihren Grundlagen erkannt sein wird, wird sie die Pforte sein zu einer bedeutungsvollen Weltanschauung, die in das Lebendige hineinführt. Goethe ist der Anschauung, wenn ich mich populär ausdrücken soll, dass bei jedem Lebendigen, zum Beispiel bei der Pflanze, ein einzelnes Organ, das grüne Pflanzenblatt, der einfachere Ausdruck, die einfachere Offenbarung der ganzen Pflanze ist. Und wiederum die ganze Pflanze ist nur die komplizierte Ausgestaltung des einzelnen Blattes. Und was Goethe nur auf die Form angewendet hat, man kann es anwenden auf die Bewegungen, die in einem Organismus zum Ausdrucke kommen.

Und es wird besonders bedeutungsvoll, wenn man diese Anschauung anwendet so, dass man künstlerisch aus dem Menschen herausholt, was in dem ganzen Menschen an Bewegungsanlagen vorhanden ist. Da stellt sich nämlich etwas sehr Interessantes heraus. Es stellt sich heraus, dass man die Bewegungen, die durch das charakterisierte sinnlich-übersinnliche Schauen als zugrunde liegend unserer Sprache wahrgenommen werden können, dass man diese Bewegungen übertragen kann auf den ganzen Menschen. So, wie die ganze Pflanze morphologisch, formell, eine komplizierte Ausgestaltung des einzelnen Blattes ist, so kann man den ganzen Menschen in seinen Gliedern sich so bewegen lassen, dass er ein lebendiger Kehlkopf wird. Dann führt der ganze Mensch aus dasjenige, was uns sonst unsichtbar, was uns unbeachtet bleibt, wenn wir zuhören dem Sprechen.

Sehen Sie, auf der einen Seite schafft man ein Werkzeug für eine Kunst. Den ganzen Menschen schafft man zum Werkzeuge für diese eurythmische Kunst. Und da aus dem ganzen Menschen herausgeholt werden können dieselben Bewegungen, die das Organ des Kehlkopfes und seiner Nachbarorgane macht, so wird der ganze Mensch zu einem sichtbaren Sprachausdruck. Wenn man bedenkt, dass der Mensch so, wie er in seiner Organisation vor uns steht - in der Tat, man muss ihn nur durchschauen, um das zu erkennen -, eine Zusammenfassung ist von all dem, was sonst in dem ganzen Universum, das uns zugänglich ist, ausgebreitet ist, wenn man dies bedenkt, dann erkennt man, dass sich die Eurythmie bedient als ihres Ausdrucksinstrumentes des kompliziertesten Werkzeuges, desjenigen Werkzeuges, das am meisten Geheimnisse des Universums enthält. Man kommt da wirklich, wenn man so den ganzen Menschen zum Kehlkopfe macht, nahe dem, was Goethe so schön charakterisiert als seine Anschauung von der Beziehung des Menschen zur Natur und zur Kunst, indem er sagt: Wenn der Mensch an den Gipfel der Natur gestellt ist und sich selber als diesen Gipfel fühlt, so bringt er in sich wiederum eine höhere Natur hervor, sodass er sich endlich, indem er zusammennimmt Maß, Ordnung, Harmonie und Bedeutung, zur Produktion des Kunstwerkes erhebt. - Man erhebt sich aber insbesondere zur Produktion des Kunstwerkes, wenn man nun den Menschen selbst als Ausdrucksinstrument für diese Kunst benützt.

Nun wird aber zu gleicher Zeit noch etwas anderes erreicht. Das Wesentliche des Künstlerischen liegt ja darinnen, dass, indem wir uns in das Kunstwerk versenken, wir zum Schweigen bringen alles Verständige, alles Intellektuelle, alles dasjenige, was bloß in Begriffen und Ideen lebt. Je mehr die Kunst Ideen und Begriffe enthält, desto weniger ist sie Kunst. Wenn man mit Umgehung alles Begrifflichen, Vorstellungsmäßigen den ganzen Menschen vertieft in die Offenbarung der Naturgeheimnisse, man kommt damit näher, dass man die Ideen ausschließt, dem wahren Weben und Walten der Naturgeheimnisse. Dann ist dieses Wahrnehmen, dieses ideen- und begriffelose Wahrnehmen und Sich-Versenken in die Dinge das Künstlerische gerade.

Und das Schaffen in solchen Geheimnissen des Universums, die nicht begrifflich zu erfassen sind, sondern die mit Ausschluss des Begrifflichen, des Ideenhaften durch die Versenkung des ganzen Menschen in sie hinein erfasst werden müssen, das ist im höchsten Maße eigentlich zu erreichen durch die Eurythmie. Denn ich habe Ihnen gesagt: Im gewöhnlichen Sprechen fließen zusammen zwei Elemente, das Gedankenelement und das Willenselement. Indem man nun überträgt die Bewegungstendenzen des Kehlkopfes und seiner Nachbarorgane auf den ganzen Menschen, sodass man durch diesen ganzen Menschen eine stumme Sprache schafft, schaltet man aus gerade das Gedankenelement und das Willenselement, das da wurzelt im ganzen Menschen. Das kommt dann durch die Bewegungen zum Ausdrucke, die Sie auf der Bühne sehen. Und so werden Sie auf der einen Seite sehen in den einzelnen Darstellungen etwas wie den ganzen Menschen als einen bewegten Kehlkopf, Sie werden Menschengruppen sehen, Sie werden auch Bewegungen des einzelnen Menschen im Raume sehen, Bewegungsverhältnisse der einzelnen Mitglieder der Gruppen zueinander.

Wenn man so die eurythmische Kunst ausgestaltet, wie ich es geschildert habe, dann wird es einem ganz selbstverständlich, dass man auch dasjenige zum Ausdruck bringen will, was durch unsere Worte fließt an Seelenwärme, an Enthusiasmus, an Lust und Leid, an Freude und Schmerz, an Erhebung und so weiter. Alles dasjenige, was so, ich möchte sagen mehr vom Herzen aus das Sprachelement durchwallt und durchwebt, das wird durch die Bewegungen des einzelnen Menschen im Raume und durch die Bewegungen der Gruppen, durch die Verhältnisse der Gruppen untereinander zum Ausdrucke gebracht, während das eigentliche Sprachelement, also dasjenige, was im Laut und in der Lautfolge liegt, durch den ganzen Menschen, indem er seine Glieder bewegt, zum Ausdrucke gebracht wird.

Damit aber unterscheidet sich dasjenige, was wir hier als Eurythmie versuchen, von allen Nachbarkünsten. Wir wollen mit diesen Nachbarkünsten, mit den verschiedenen Arten von Tanzkünsten durchaus nicht konkurrieren. Wir wissen ganz gut, dass die in ihrer Art heute selbstverständlich vollkommener sind als unsere Eurythmie, die erst im Anfange ihrer Bestrebungen ist. Aber sie ist ja auch etwas ganz anderes. Diese Künste bringen einen Zusammenhang zwischen der Gebärde der Bewegung und dem Seelischen, der gewissermaßen ein Augenblickszusammenhang ist. Aber alles dasjenige, was so pantomimisch, mimisch durch Augenblicksgesten zum Ausdrucke gebracht werden kann, das ist in unserer Eurythmie nicht angestrebt. So, wie das Sprechen selbst durchaus gesetzmäßig verläuft, so wie das Musikalische gesetzmäßig verläuft, so besteht auch eine streng innerliche Gesetzmäßigkeit in demjenigen, was wir eurythmisch anstreben. Wenn noch etwas Pantomimisches, etwas Mimisches durchdringt, so ist das noch eine Unvollkommenheit und wird später abgestreift werden, wenn die eurythmische Kunst vollkommener und vollkommener wird.

Daher ist auch nichts Willkürliches in den Dingen. Wenn zwei Menschen oder zwei Menschengruppen an verschiedenen Orten ein und dieselbe Sache eurythmisch darstellen würden, so würde der individuellen Auffassung kein größerer Spielraum gestattet sein, als gestattet ist, wenn zwei Klavierspieler ein und dieselbe Beethoven’sche Sonate nach ihrer Auffassung individuell zur Darstellung bringen. Alles Willkürliche ist ausgeschlossen. Es ist eine gesetzmäßige, stumme Sprache. Daher kann heute noch, wo selbstverständlich noch nicht jedermann bei dem Eurythmischem als solchem dabei sein kann, dieses Eurythmische begleitet werden auf der einen Seite von dem Musikalischen, das ja schließlich der Ausdruck desselben ist, aber auch begleitet werden von der Rezitation.

Und gerade bei der Rezitation zeigt sich, wie Kunst zu Kunst sich findet, wenn man sie mit der Eurythmie zusammenstellt. Da kann man nicht so rezitieren, wie es heute beliebt ist zu rezitieren. Heute ist, wenn man rezitiert, ganz besonders das unkünstlerische Element der Dichtung bevorzugt. Es wird ja heute viel darauf gesehen beim Rezitieren, dass im Grunde der Prosainhalt durch das Rezitieren zum Ausdrucke kommt. Und das liebt man auch. Das ist ein Unkünstlerisches. Man fühlt dieses Unkünstlerische, wenn man sich erinnert erstens, wie gewisse Arten, ich möchte sagen von primitiver Rezitation sich zur Geltung gebracht haben in primitiven Kulturen. Man konnte es - diejenigen Leute, die jetzt älter geworden sind, konnten das auf dem Lande draußen noch erleben -, man konnte es sehen, wenn so die Bänkelsänger herumzogen, wie sie durchaus mit Gebärden, die aber sehr natürliche Gebärden waren, nicht in dem Sinne, wie man das heute natürlich nennt, sondern die sogar unseren eurythmischen Gebärden sehr ähnlich waren, wie sie mit solchen Gebärden begleiteten, oftmals mit Herumgehen des ganzen Körpers begleiteten dasjenige, was sie zur Darstellung brachten im Rezitativ.

Und schließlich liegt ja der wirklichen Dichtung nicht der Prosainhalt als die Hauptsache zugrunde, sondern das Rhythmische, das Formelle, das Formale, das Taktmäßige, das Gesetzmäßige in der Aufeinanderfolge des Hörbaren. Schiller hatte bei den bedeutsamsten seiner Gedichte zunächst nicht den wortwörtlichen Inhalt in der Seele, sondern er hatte in der Seele etwas unbestimmt Melodiöses, und zu diesem unbestimmt Melodiösen, in dem gar noch nichts Wortwörtliches war, gesellte er erst hinzu den wortwörtlichen Inhalt. Überall sollte man fühlen das Gestaltende, das zugrunde liegt jeder wirklichen Dichtung. Die meisten Dinge, die man heute Dichtungen nennt, sind ja keine Dichtungen. Es wird heute so viel gedichtet, dass eigentlich um neunundneunzig Prozent zu viel gedichtet wird. Aber man würde nicht mit der heute beliebten Rezitationskunst, die den wortwörtlichen Prosainhalt besonders berücksichtigt, die Eurythmie begleiten können.

So wird hier versucht, auch in der Rezitationskunst zurückzugehen zu dem wirklich Künstlerischen. Goethe hat noch mit dem Taktstock in der Hand wie ein Kapellmeister selbst seine «Iphigenie», also eine dramatische Dichtung, mit seinen Schauspielern einstudiert, hinsehend auf das, was als das wirklich künstlerisch Formale liegt zugrunde demjenigen, wodurch sich das wirklich Künstlerische zum Ausdrucke bringt, nicht im Prosaelemente, dem wortwörtlichen Inhalt. Und so ist es insbesondere, dass man dasjenige, was sonst in der Dichtung zum Ausdrucke kommt durch das Wort, dass man das in seinem Willenselemente darstellen kann durch die eurythmische Kunst. Sie werden also rezitieren hören Gedichte, Sie werden diese Gedichte in der stummen eurythmischen Sprache auf der Bühne vorgeführt sehen.

Ich glaube, es zeigt sich insbesondere gerade an Goethe’schen Gedichten die Berechtigung dieser eurythmischen Kunst. Wir werden Ihnen heute zum Beispiel vorführen eurythmische Darstellungen für Goethes Wolkengedichte. Goethe hat ja seine Metamorphosenanschauung auch - mehr sie veräußerlichend, aber dadurch eben gerade ins Künstlerische übertragend - auf die sich verwandelnden Wolkengebilde Stratus, Cumulus, Cirrus, Nimbus angewendet. Wie sich diese Wolkengebilde ineinander verwandeln, Goethe hat es in wunderschönen Versen zur Anschauung gebracht, eine Anschauung, die ihm aufgegangen ist, als er gelesen hat den Wolkenbeobachter Howard. Er hat ein sehr schönes Gedicht «Zu Howards Ehrengedächtnis» verfasst, das wir ebenfalls Ihnen heute eurythmisch zur Darstellung bringen werden. Aber gerade, wenn man solche Dichtungen Goethes hat, in denen es so recht darauf ankommt, ein in der Natur sich Gestaltendes in der Dichtung mit solchen Formen zu verfolgen, dass das sich in der Natur Gestaltende nachquellt und nachwallt in dem Rhythmus und in der Formgebung des Sprachlichen, dann kann man auch mit den Formen der Eurythmie nachfolgen der Dichtung. Und deshalb glaube ich, dass gerade an diesen Wolken-Dichtungen Goethes schön zum Ausdrucke gebracht werden kann, wie völlig adäquat gefunden werden kann der eurythmische Ausdruck für dasjenige, was auf der anderen Seite auch dichterisch zum Ausdrucke gebracht werden kann.

Nun gibt es ein Gedicht Goethes, in dem Goethe ja selber die ganze Art seines Metamorphosengedankens, seiner Metamorphosenempfindung zum Ausdrucke gebracht hat, in dem Gedicht «Die Metamorphose der Pflanzen». Das ganze Gedicht lebt in der Darstellung von Formanschauung. Von Zeile zu Zeile haben wir eigentlich das Gefühl, dass wir nicht haften bleiben dürfen an der abstrakten Idee, sondern dass wir uns mit unserer ganzen Seele folgsam zeigen müssen den Formen, die in des Dichters Phantasie wogen und wallen. Und daher kann man gerade diesem Metamorphosengedichte Goethes die eurythmische Darstellung voll anpassen. Und wir haben versucht, für die heutige Aufführung auch dieses Gedicht Goethes über die Metamorphose der Pflanzen in eurythmische Formen umzugießen. Gerade da, wo die Dichtung selber wird wie ein unmittelbar durch die Seele geschaffener Abdruck der in der Natur waltenden Geheimnisse, da offenbart sich auf der einen Seite das Künstlerisch-Werden des menschlichen Empfindens selber, auf der anderen Seite die Möglichkeit, dieses Künstlerische auch so zur Darstellung zu bringen, wie cs gebracht werden kann, wenn der ganze Mensch, wie ich es angedeutet habe, als gewissermaßen musikalisch-sprachliches Instrument benützt wird. So dringen wir wohl in Naturgeheimnisse tief hinein, wenn wir in dieser Formsprache diese Geheimnisse suchen, die wir in der Eurythmie zur Offenbarung zu bringen bestrebt sind.

Nur bitte ich Sie, alles dasjenige, was wir heute, was wir gegenwärtig schon als Probe dieser unserer eurythmischen Kunst vorbringen können, eben durchaus als einen Anfang zu betrachten, vielleicht als den Versuch eines Anfanges. Wir sind selbst in Bezug auf dasjenige, was wir heute schon können, die strengsten Kritiker. Allein, wir sind auch überzeugt, wenn dasjenige, was darinnen lebt in dem Versuch einer neuen Kunst, entweder noch durch uns selbst oder wahrscheinlich durch andere weiter zur Ausbildung gebracht wird - und es liegen viele, viele Entwicklungsmöglichkeiten darinnen -, dann wird sich diese eurythmische Kunst als vollberechtigte Kunstform neben andere vollberechtigte Kunstformen gewiss einmal hinstellen können. Wie gesagt, wir denken über das, was wir heute schon bieten können, durchaus bescheiden, und ich bitte Sie deshalb, auch dasjenige, was wir Ihnen darstellen werden, mit Nachsicht als den Anfang einer neuen Kunstform aufzunehmen.