The Origin and Development of Eurythmy

1918–1920

GA 277b

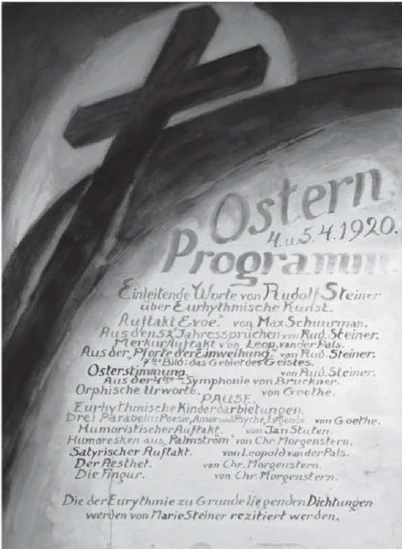

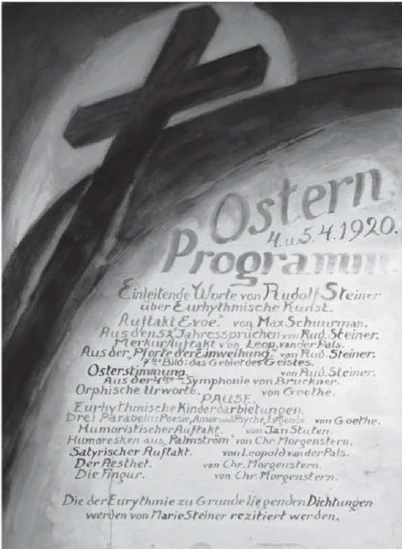

4 April 1920 (Easter Sunday), Dornach

Translated by Steiner Online Library

55. Eurythmy Performance

Dear Ladies and Gentlemen,

As always before these eurythmy performances, allow me to say a few words today as well. What we will present to you today in a rehearsal of eurythmy is an attempt at a new art form.

On the stage, you will see all kinds of movements that people perform on themselves through their limbs, or that are performed by people in space, by individual people in space, or also alternating movements, alternating positions of groups of people. These movements, which will be demonstrated, are intended to be the expression of poetry or even of music. Now, one could initially interpret these movements simply as gestures. But they are not. For everything in which you are to find the art of eurythmy is not arbitrary gestures associated with something poetic, but rather they are thoroughly lawful expressions of what is experienced by the soul — like language itself.

An attempt has been made to give a real mute language in this eurythmy, a language that consists of human movements. The way in which this is attempted is entirely in line with the spirit of Goethe's world view. However, one must not misunderstand the manifold aspects of this Goethean world view and also understand how to develop it further. Eurythmy is truly that which Goethe calls the expression of the sensual and the supersensible. For it is based on the study of the impulses and tendencies of movement that are set in motion in the human larynx and all those organs that connect to the larynx when speaking, for the language that is contained within.

Phonetic language is used as a means of poetic expression. However, it can be said that the more advanced a culture is, the more phonetic language approaches the prosaic as a means of expression. If we go back to the poetry of earlier times, we can see that in earlier times, poetry was still seen in what actually lies behind the actual prosaic nature of language, in the rhythms, in the rhythmic movement of language, and also in the plastic imagery that is expressed through language. This song-like and plastic character of language is increasingly being stripped away, the more language takes on the character given to it by the advance of spiritually inanimate movement. In particular, because speech is there for human understanding, for conversation, an unartistic element flows more and more into speech.

In this inartistic spoken language, however, one can seek out what lies at its artistic core. In it - in this phonetic language - two human revelations flow together, from two very different sides: on the one hand, the revelation of thoughts, everything that is thought and imagined, so to speak, everything that flows from the human head into the larynx, that is the one element of phonetic language. The other element is everything that comes from the whole human being: it is the will element in speech. One can say: the laws of the will, the inner soul life revealed in the will, flow together when one forms speech artistically, most especially.

But just as in every art there is less that is truly artistic the more that is ideational and mental that flows into it, so too in what is presented poetically there is less that is truly artistic as the thought - which is a prosaic element - flows into this artistic element. The actual poetry is given in the will element, which lives itself out in rhythm and beat, in the whole formation, and which also lives itself out in the images on which it is based.

Now, in eurythmy, it is precisely the task of stripping away that which is the thought element. This is then emphasized in the recitation that accompanies the eurythmy, but which must also be shaped in a special way for the eurythmy, as I will mention in a moment. In contrast, in the movements of the eurythmy itself, one will strip away everything that is conceptual. The whole human being is made the subject of expression: everything that is done in the way of movements as silent speech is now the expression not of thoughts but of the will element, which is expressed through the whole human being - namely through everything that is connected, that integrates into the rhythmic system, into the heart system and so on.

But in order to be able to do this, to really bring the element of will to manifestation through movements like a mute language, it is necessary to study the movement tendencies of the larynx and the other speech organs. When we speak, it is clear that our larynx and speech organs are in motion. One need only think of the fact that while I am speaking here, the air comes into certain lawful movements, which movement is simply a continuation of the movements initiated by the larynx and its neighboring organs. But it is not so much these movements that are of interest for eurythmy. Rather, it is the movements, seen supersensibly, that are the potential movements. And according to Goethe's law of metamorphosis, according to which the whole organism is only a more complicated form of a single organ, one can bring the whole person into such movement, as the larynx actually wants to develop in speech.

This is the study that must underlie this mute language, which comes to the fore in eurythmy. You see, as it were, the whole human being become the moving larynx. The movements are only different from those that function in phonetic language because in phonetic language the cartilages of the larynx collide directly with the outside air, while in euryth we let that which pours out of the will element strike together with the muscles, which offer a much stronger resistance to what is brought to the fore by the will. That is why these movements occur in a slowed-down form in eurythmy, which come to the fore in swinging oscillatory movements when speaking aloud, as it were, summing up the swinging movement into one main form. And that is expressed through the whole of the human personality, through the whole of the muscular organization. That is the mute language of eurythmy.

Therefore, in the succession of movements, it is something that represents a law as necessarily as the musical element itself represents a law in the succession of the melodious element or in the juxtaposition of what represents a law as does the harmonic element in music. And just as little as more than a certain degree of subjective interpretation comes into it when two pianists play the same sonata independently of each other, so it is also in eurythmy when the same thing, the same poem is presented by two personalities or by two groups. Thus, the individual element is no more distinct than the individual interpretation of two piano players of the same Beethoven sonata. There is nothing arbitrary in this artistic eurythmy, but everything is just as internally lawful as in music itself.

This makes eurythmy, this silent language, particularly suitable for serving Goethe's demand to bring a sensual and supersensory element into artistic representation, because it dissociates the prosaic, the thought element, from the poetry and translates into visible movement what is actually artistic in it. One could also say: sculpture in motion, gestures that take hold of the whole human being, understood as language, as real language, as unambiguous language. This is what should come to the fore in eurythmy.

Therefore, you will see that this silent language can be accompanied on the one hand by the musical element and on the other by the poetic element in the recitation, which, however, as such, as the art of recitation, must in turn return to the earlier good forms of reciting, where one recited according to measure and rhythm, not according to the prose content of the poem, after which one has just now especially formed the art of recitation and sees something perfect in this prosaic form of the art of recitation.

How great poets did not consider this prosaic element, to which so much importance is attached in today's unartistic age, to be the main thing, can be seen from the fact that Schiller, for example, never had the literal content of a poem in mind, at least not in his great poems. He always had something vague and melodious in his soul, and only then did he add the literal content. Goethe even rehearsed his Iphigenia with his actors like a conductor rehearsing a piece of music with a baton, not emphasizing the content of the prose during the recitation, but rather the artistic, rhythmic, and metrical form, the plastic, musical element in the poetic, which is, after all, what is truly artistic in the poetic.

Then we shall see how that which is already eurythmically shaped in the imagination, such as my [mystery drama] scenes, which are also being presented today, express the expressions of the laws of the human soul, and the paths that this soul life can take, as well as that which is already inwardly formed in the feeling, and how that can be expressed quite naturally in eurythmy. In scenes like these, we can see how we must develop towards an understanding of the life of nature and the world, so that we no longer base our understanding of the life of nature and the world merely on intellectual abstractions, but on imaginations — imaginations such as I have attempted in my mystery scenes, of which a rehearsal will also be given today. For the fact that human development must go in this direction is in line with a deep conviction that one gains when one has any insight at all into the workings of human and non-human nature. What use is it, dear attendees, to philosophize about the fact that real knowledge, real understanding, only exists in the rational, clearly analyzable, when nature does not give up its essence to the analyzable, the discursive, the rational alone. If nature works in images that only reveal the inner essence of nature as images, then it is necessary that we also penetrate into the inner essence of the existence of the world through images, through imagination.

The fact that people wanted to understand nature only with their minds actually led them to say, cowardly:

No created spirit penetrates into the depths of nature

Happy he to whom she shows only the outer shell.

Goethe, in his old age, when he was truly able to think more clearly about such things than many who philosophize rationally, said of these words of Haller's – “No created spirit penetrates into the innermost being of nature; blessed is he to whom it shows only the outer shell” – Goethe said:

“Into the innermost part of nature”

Oh, you philistines!

“No created spirit can penetrate."

May you not remind me and my brothers and sisters

of such a word:

We think: place by place

we are within.“

“Happy the man to whom she shows

Only the outer shell!”

That's what I've heard repeated for sixty years,

I curse it, but furtively;

Tell me a thousand, a thousand times:

She gives everything abundantly and gladly;

Nature has neither core

Nor shell,

She is everything at once;

She only tests you, most of all,

Whether you are core or shell.

So it is: the one who does not want to be shell with his soul, that is, a bundle of intellectual ideas, must move up to images. But then knowledge connects with art. And then one can say, say with understanding, what Goethe also demanded of true art: that it is a manifestation of secret laws of nature that could never come to revelation without it. And one understands Goethe's other feeling about nature and art: “When nature begins to reveal her manifest secret to someone, they long for her most worthy interpreter, art.”

This kind of world view, this Goetheanism, underlies what we want to present in eurythmy here. In the second part, after the break, you will see that our children's eurythmy demonstration – a presentation of eurythmic poems by children – shows the very strong hygienic and educational side of this eurythmy. Ordinary gymnastics, the one-sidedness of which is still not recognized by the public today, will have to be supplemented because it only takes into account the physiological aspects of the human being, the soul of the movements that the human being performs as a child. And only the art of movement imbued with soul, eurythmy, will truly make the human being strong-willed, while mere gymnastics may make the body strong, but not at the same time the soul, and in particular does not draw the initiative of the will from within. Eurythmy can bring the initiative of the will from within the human being.

But all in all, we must ask you to be patient, because what is being attempted as a new art form is still in its infancy. It is an attempt at the beginning of what I have presented to you more or less as the ideal of this art. But those who saw this eurythmy here months ago and will see it again now will see that we have worked on it, that we have achieved a great deal in the formation of the groups and also in the formation of the movements of the individual compared to before. We are the harshest critics of our performances and we know that the eurythmic art is in its infancy. But we also believe that, if it is further perfected either by us or probably by others, it will one day be able to take its place as a younger, fully-fledged art alongside other, older, fully-fledged art forms.

Ansprache zur Eurythmie

Meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden!

Gestatten Sie, dass ich auch heute, wie immer vor diesen eurythmischen Darstellungen, ein paar Worte vorausschicke. Dasjenige, was wir als Eurythmie auch heute wiederum in einer Probe uns gestatten Ihnen vorzuführen, das ist der Versuch einer neuen Kunstform.

Sie werden auf der Bühne allerlei Bewegungen sehen, die der Mensch durch seine Glieder an sich selber ausführt oder die ausgeführt werden von Menschen im Raume, von einzelnen Menschen im Raume, oder auch Wechselbewegungen, Wechselstellungen von Menschengruppen. Diese Bewegungen, die da vorgeführt werden, sie sollen der Ausdruck sein für Dichterisches oder auch wohl für Musikalisches. Nun könnte man diese Bewegungen ja zunächst einfach als Gebärden deuten. Das sind sie nicht. Denn alles dasjenige, worinnen Sie eurythmische Kunst finden sollen, sind nicht willkürliche Gebärden, die mit irgendetwas Dichterischem in Verbindung gebracht werden, sondern es sind durchaus gesetzmäßige Ausdrücke des von der Seele Erlebten — wie die Sprache selbst.

Es ist versucht [worden], in dieser Eurythmie eine wirkliche stumme Sprache zu geben, eine Sprache, die in menschlichen Bewegungen besteht. Die Art und Weise, wie das versucht wird, ist ganz gelegen im Sinne der Goethe’schen Weltanschauung. Nur muss man dasjenige, was an Mannigfaltigem in dieser Goethe’schen Weltanschauung liegt, nicht missverstehen und auch es weiter auszubilden verstehen. So recht ist die Eurythmie das, was Goethe die Ausdrucksform des Sinnlich-Übersinnlichen nennt. Denn zugrunde liegt das Studium der Bewegungsimpulse und Bewegungstendenzen, die bei der Lautsprache im menschlichen Kehlkopf und all denjenigen Organen, die mit dem Kehlkopf sich verbinden, für die Sprache in Bewegung versetzt werden, die darinnen gelegen sind.

Die Lautsprache, sie dient ja als dichterisches Ausdrucksmittel. Allein, man kann gerade sagen: Je weiter irgendeine Kultur vorrückt, desto mehr nähert sich die Lautsprache in ihrem ganzen Charakter dem Prosaischen als Ausdrucksmittel. Gerade wenn man an das Dichterische früherer Zeiten zurückgeht, so kann man sehen: Das Dichterische wurde in früheren Zeiten durchaus noch gesehen in dem, was eigentlich hinter dem eigentlich Prosaischen der Sprache liegt, in den Rhythmen, in der rhythmischen Bewegung der Sprache, auch in der plastischen Bildergestaltung, die durch die Sprache zum Ausdruck kommt. Dieser gesangartige und plastische Charakter der Sprache, die werden immer mehr und mehr abgestreift, je mehr die Sprache annimmt den Charakter, der ihr verliehen wird durch das Vorrücken der geistig unbelebten Bewegung. Insbesondere auch dadurch, dass ja die Lautsprache da ist zum Menschenverständnis, da ist also zur Konversation, dadurch fließt immer mehr und mehr in die Lautsprache ein unkünstlerisches Element hinein.

In dieser unkünstlerischen Lautsprache kann man aber dasjenige aufsuchen, was in ihr als das eigentlich Künstlerische zugrunde liegt. In ihr - in dieser Lautsprache - fließen ja zwei menschliche Offenbarungen zusammen, von zwei ganz verschiedenen Seiten her: Auf der einen Seite die Offenbarung der Gedanken, alles Gedanken- und Vorstellungsmäßige, gewissermaßen alles dasjenige, was aus dem Kopfe des Menschen in den Kehlkopf fließt, das ist das eine Element der Lautsprache. Das andere Element ist alles dasjenige, was aus dem ganzen Menschen kommt: Es ist das Willenselement in der Sprache. Man kann schon sagen: Die Gesetzmäßigkeit des Willens, das innere im Willen sich offenbarende seelische Leben, sie fließen zusammen, wenn man die Lautsprache künstlerisch gestaltet, ganz besonders.

Aber wie in jeder Kunst umso weniger wirklich Künstlerisches vorhanden ist, je mehr Ideelles gedankenmäßig in sie einfließt, so ist eigentlich auch in dem, was dichterisch dargeboten wird, umso weniger wirklich Künstlerisches, als der Gedanke - der ja ein prosaisches Element ist - einfließt in dieses Künstlerische. Das eigentlich Dichterische ist im Willenselement gegeben, das sich eben auslebt in Rhythmus und Takt, in der ganzen Formung, das sich auch auslebt in den Bildern, die zugrunde liegen.

Nun handelt es sich gerade bei der Eurythmie darum, abzustreifen dasjenige, was Gedankenelement ist. Es kommt dann zur Geltung in der die Eurythmie begleitenden Rezitation, die aber auch in einer besonderen Weise für die Eurythmie gestaltet werden muss, wie ich gleich erwähnen werde. Dagegen in den Bewegungen der Eurythmie selber wird man abstreifen alles Gedankenmäßige. Der ganze Mensch [wird] zum Subjekt des Ausdruckes gemacht: Alles dasjenige, was an Bewegungen, als stumme Sprache sich vollzieht, ist der Ausdruck jetzt nicht der Gedanken, sondern des Willenselementes, das sich durch den ganzen Menschen - namentlich durch alles dasjenige, was zusammenhängt, was sich eingliedert auch in das rhythmische System, in das Herzsystem und so weiter —, was da zum Ausdrucke kommt.

Dazu aber, dass man das könne, dass man wirklich das Willenselement durch Bewegungen wie eine stumme Sprache zur Offenbarung bringen kann, dazu ist notwendig, dass man studiere die Bewegungstendenzen des Kehlkopfes und der anderen Sprachorgane. Wenn wir sprechen, das ist ja klar, sind unser Kehlkopf und die Sprachorgane in Bewegung. Man braucht nur daran zu denken, dass, während ich hier spreche, ja die Luft in gewisse gesetzmäßige Bewegungen kommt, welche Bewegung ja einfach eine Fortsetzung desjenigen ist, was der Kehlkopf und seine Nachbarorgane an Bewegungen einleiten. Aber nicht so sehr diese Bewegungen, die ja auch schon — weil wir beim gewöhnlichen Sprechen unsere Aufmerksamkeit dem Gehörten zuwenden -, die also als Nichtgehörtes schon zu dem SinnlichÜbersinnlichen gehören, nicht so sehr diese Bewegungen sind es, die für die Eurythmie in Betracht kommen, sondern die Bewegungen, übersinnlich gesehen, die Bewegungsanlagen sind. Und man kann nach dem Goethe’schen Metamorphosengesetz, nach dem der ganze Organismus nur eine kompliziertere Ausgestaltung eines einzelnen Organes ist, man kann den ganzen Menschen in solche Bewegung bringen, wie sie eigentlich der Kehlkopf in der Lautsprache entwickeln will.

Das ist das Studium, welches zugrunde liegen muss dieser stummen Sprache, die in der Eurythmie zum Vorschein kommt. Sie sehen gewissermaßen den ganzen Menschen zum bewegten Kehlkopf geworden. Die Bewegungen sind nur andere, als sie bei der Lautsprache funktionieren, aus dem Grunde, weil bei der Lautsprache die Knorpel des Kehlkopfes unmittelbar mit der äußeren Luft zusammenschlagen, während wir bei der Eurythmie zusammenschlagen lassen dasjenige, was sich aus dem Willenselement ergießt, zusammenschlagen lassen mit den Muskeln, die einen wesentlich stärkeren Widerstand entgegensetzen demjenigen, was da durch den Willen zum Vorschein kommt. Daher treten in verlangsamter Form diese Bewegungen in der Eurythmie auf, die in schwingenden Oszillationsbewegungen beim Lautsprechen zum Vorschein kommen, gleichsam summiert die schwingende Bewegung zu einer Hauptform. Und das ist ausgedrückt durch das Ganze der menschlichen Persönlichkeit, durch das Ganze der Muskelorganisation. Das ist diese stumme Sprache der Eurythmie.

Daher ist sie etwas, was in der Aufeinanderfolge der Bewegungen etwas so notwendig Gesetzmäßiges darstellt wie das Musikalische selber in der Aufeinanderfolge des melodiösen Elementes oder in der Nebeneinanderstellung, was etwas so Gesetzmäßiges darstellt wie das harmonische Element in der Musik. Und ebenso wenig, wie, wenn ein und dieselbe Sonate zwei Klavierspieler unabhängig voneinander spielen, mehr als nur bis zu einem gewissen Grade von der subjektiven Auffassung hineinkommt, so ist es auch in der Eurythmie, wenn ein und dieselbe Sache, ein und dieselbe Dichtung von zwei Persönlichkeiten dargestellt wird oder von zwei Gruppen. So ist dasjenige, was durch Individuelles hineinkommt, nicht stärker verschieden als die individuelle Auffassung zweier Klavierspieler von ein und derselben Beethovensonate. Es ist also nichts Willkürliches in diesem eurythmisch Künstlerischen drinnen, sondern es ist alles ebenso innerlich gesetzmäßig wie bei der Musik selbst.

Dadurch ist dieses Eurythmische, diese stumme Sprache auch besonders geeignet — weil es das Prosaische, das Gedankenelement loslöst von der Dichtung und das unter der Dichtung liegende, eigentlich Künstlerische in anschaubare Bewegung übersetzt -, so ist es möglich, gerade damit der Forderung Goethes zu dienen, ein sinnlich-übersinnliches Element hineinzubringen in die künstlerische Darstellung. Plastik in Bewegung, so könnte man auch sagen, Gebärde, die den ganzen Menschen ergreift, als Sprache, als wirkliche Sprache aufgefasst, als eindeutige Sprache aufgefasst, das soll in der Eurythmie zum Vorschein kommen.

Daher werden Sie sehen, dass diese stumme Sprache begleitet werden kann auf der einen Seite von dem musikalischen Element und auf der anderen Seite von dem dichterischen Elemente in der Rezitation, die aber als solche, als Rezitationskunst, auch wiederum zurückkehren muss zu den früheren guten Formen des Rezitierens, wo man rezitierte nach Takt und Rhythmus, nicht nach dem Prosagehalt der Dichtung, nach dem man gerade heute besonders die Rezitationskunst hin gebildet hat und in dieser prosaischen Ausgestaltung der Rezitationskunst gerade etwas Vollkommenes sieht.

Wie große Dichter durchaus nicht dieses prosaische Element, auf das heute in unserem unkünstlerischen Zeitalter so viel Wert gelegt wird, gerade das nicht für die Hauptsache gehalten haben, das geht daraus hervor, dass zum Beispiel Schiller niemals zuerst den wortwörtlichen Inhalt einer Dichtung im Sinne gehabt hat oder in der Secle gehabt hat, wenigstens bei seinen großen Dichtungen nicht. Er hatte da immer mehr ein Unbestimmt-Melodichaftes in der Seele, und an das gliederte er erst den wortwörtlichen Inhalt an. Goethe studierte sogar seine «Iphigenie» mit seinen Schauspielern wie der Kapellmeister ein Musikstück so mit dem Taktstock ein, nicht auf den Prosainhalt bei der Rezitation das Wesentliche legend, sondern auf die künstlerische, rhythmische, taktmäßige Gestaltung, auf das plastische, musikalische Element im Dichterischen, was ja im Dichterischen das eigentlich Künstlerische ist.

Dann werden wir sehen, wie dasjenige, was nun schon in der Phantasie eurythmisch gestaltet ist, wie zum Beispiel meine [Mysteriendramen-]Szenen, die heute auch zur Darstellung kommen, die ausdrücken Gesetzmäßigkeiten innerhalb des menschlichen Seelenlebens selber, Wege, die dieses Seelenleben machen kann, wie dasjenige, was schon innerlich gestaltet ist in der Empfindung, wie das ganz natürlich sich auch eurythmisch äußerlich darstellen lässt. Bei solchen Szenen wird man sehen, wie wir uns entwickeln müssen hin nach einer Auffassung auch des Natur- und Weltlebens, sodass wir nicht mehr bloß Verstandesabstraktionen zugrunde legen, wenn wir das Natur- und Weltenleben wirklich durchschauen wollen, sondern Imaginationen — Imaginationen, wie ich sie versucht habe in meinen Mysterienszenen, von denen eben auch heute eine Probe gegeben wird. Denn dass nach dieser Richtung die menschliche Entwicklung gehen muss, das entspricht einer tiefen Überzeugung, die man gewinnt, wenn man überhaupt etwas hineinschaut in das Getriebe der menschlichen und der außermenschlichen Natur. Was nützt es denn, wenn man schon philosophiert, sehr verehrte Anwesende, darüber zum Beispiel, dass wirkliche Erkenntnis, wirkliches Wissen nur bestünde in dem Verstandesmäßigen, klar Analysierbaren, wenn die Natur eben ihr Wesen nicht hergibt dem Analysierbaren, dem Diskursiven, dem Verstandesmäßigen allein. Wenn die Natur in Bildern wirkt, die nur als Bilder das innere Wesen der Natur enthüllen, dann ist es notwendig, dass wir auch durch Bilder, durch Imaginationen in das innere Wesen des Weltendaseins eindringen.

Dass die Menschen begreifen wollten nur mit dem Verstande die Natur, das führte sie eigentlich dazu, kleinmütig zu sagen:

In’s Innere der Natur dringt kein erschaffener Geist

Glückselig, wem sie nur die äußre Schale weist.

Goethe sagte aus seiner Kunst- und Weltanschauung heraus gegenüber diesen Haller’schen Worten - «In’s Innere der Natur dringt kein erschaffener Geist / Glückselig, wem sie nur die äußre Schale weist» -, Goethe sagte im hohen Alter, wo er über solche Dinge wirklich klarer dachte als viele, die verstandesmäßig philosophieren, Goethe sagte:

«Ins Innre der Natur» —

O du Philister! —

«Dringt kein erschaffner Geist.»

Mich und Geschwister

Mögt ihr an solches Wort

Nur nicht erinnern:

Wir denken: Ort für Ort

Sind wir im Innern.

«Glückselig! wem sie nur

Die äußre Schale weist!»

Das hör’ ich sechzig Jahre wiederholen,

Ich fluche drauf, aber verstohlen;

Sage mir tausend tausendmale:

Alles gibt sie reichlich und gern;

Natur hat weder Kern

Noch Schale,

Alles ist sie mit einem Male;

Dich prüfe du nur allermeist

Ob du Kern oder Schale seist.

So ist es: Derjenige, der nicht selber Schale sein will mit seiner Seele, das heißt ein Bündel von intellektuellen Vorstellungen, der muss zu Bildern aufrücken. Dann verbindet sich aber Erkenntnis mit der Kunst. Und dann kann man dasjenige sagen, verständnisvoll sagen, was Goethe auch von der rechten Kunst forderte: Dass sie eine Manifestation geheimer Naturgesetze sei, die ohne sie niemals an die Offenbarung treten könnten. Und man versteht das andere, was Goethe empfand gegenüber Natur und Kunst: Wem die Natur - so sagte er - ihr offenbares Geheimnis zu enthüllen beginnt, der sehnt sich nach ihrer würdigsten Auslegerin, der Kunst.

Solch eine Weltanschauung, solcher Goetheanismus liegt dem zugrunde, was wir hier eurythmisch darstellen wollen. Sie werden im zweiten Teile nach der Pause sehen, dass in der Vorführung unserer Kindereurythmie - Vorführung von eurythmischen Gedichten durch Kinder -, welch eine sehr stark hygienisch-pädagogische Seite diese Eurythmie hat. Das gewöhnliche Turnen, dessen Einseitigkeit man ja heute noch nicht in der Öffentlichkeit einsieht, das wird ergänzt werden müssen, weil es bloß auf das Physiologische im Menschen Rücksicht nimmt, von dem Beseelten der Bewegungen, die der Mensch ausführt als Kind. Und die beseelte Bewegungskunst, die Eurythmie, sie wird erst den Menschen wirklich willensstark machen, während ihn das bloße Bewegungs-Turnerische zwar als Leib stark macht, aber nicht eben auch gleichzeitig als Seele stark macht, namentlich nicht seine Willensinitiative herausholt aus seinem Inneren. Das Herausholen der Initiative des Willens aus dem Inneren des Menschen, das wird zustande gebracht werden durch die Eurythmie.

Aber alles in allem müssen wir Sie doch bitten um Nachsicht, weil dasjenige, was versucht wird als eine neue Kunstform, eben durchaus am Anfange steht. Es ist ein Versuch eines Anfanges zu dem, was ich mehr oder weniger als das Ideal dieser Kunst Ihnen vor Augen gestellt habe. Aber diejenigen, die als Zuschauer dieses Eurythmische vor Monaten hier gesehen haben und es jetzt wieder sehen werden, werden sehen, dass wir immerhin gearbeitet haben, dass wir namentlich in der Formung der Gruppen und auch in der Formung der Bewegungen des Einzelnen gegenüber früher manches erreicht haben. Wir sind selbst die strengsten Kritiker unserer Darbietungen und wissen genau, die eurythmische Kunst steht im Anfange. Aber wir glauben auch, die Überzeugung hegen zu dürfen, dass, wenn sie entweder durch uns oder wahrscheinlich durch andere weiter vervollkommnet sein wird, sie einstmals als jüngere vollwertige Kunst neben andere, ältere, vollberechtigte Kunstformen wird hintreten können.