Architecture, Sculpture and Painting of the First Goetheanum

GA 288

4 April 1920, Dornach

Translated by Steiner Online Library

III. The Symbolism of the Building at Dornach I

I would like to talk again today about the nature and significance of our building, for the reason that a number of external personalities are among us at the course for medical professionals.

First of all, I would like to note that this building, as a representative of our anthroposophically oriented spiritual science, is intended to be in the world that which really gives an outward image of the significance and inner essence of this movement. If one wants to recognize this movement in its true significance, one must surely become familiar with the fact that this movement wants to enter the most diverse areas of life as something completely new, that its appreciation must arise from the realization that such a new thing is necessary in the face of the fact that old impulses in our present time clearly show how they are moving straight into decadence.

If our movement had not emerged from that which the signs of the times themselves demand, from that which is not now in any human program, but from that which can be read in the spiritual development of humanity that lies behind our physical human movement, even if our movement were like so many other movements that also found societies, set up programs, and set up so-called ideals, then at a certain point this movement would have needed a larger building, larger premises for its membership, and they would have turned to some outside builder to have a house built. The architect would have built something in the traditional style, and the Society would have carried on its work in such a building.

This is not how it should be with us. Rather, since we came to the point of being able to start a building project – which might even be completed one day – it had to be shown, precisely on the basis of this fact, how this spiritual movement, on the one hand, reaches the highest heights of spiritual life and, on the other hand, is a thoroughly practical movement that can directly engage with all aspects of practical life. That means that it had to be shown that our anthroposophically oriented spiritual movement is capable of producing new building forms, a new architectural style, out of itself. It had to be shown that our movement, down to the last detail, is not just a theoretical world-view movement, but something that can have a formative effect on everything that is placed externally in the physical world.

Thus this building was not constructed as an outwardly unimportant house, but was built out of spiritual science, out of its very own feelings, ideas and thoughts, and in every detail it is an expression of what this spiritual science wants to be. It does not want to be some mystical driveling, it does not want to be some abstract theory, but it wants to be something that can deeply intervene in the most everyday life, and must therefore also intervene most in that which is to be its own representative. The whole of this structure should express how it places itself in the present as a living protest against what the centuries, the millennia, have brought to humanity and what is currently leading humanity to decline.

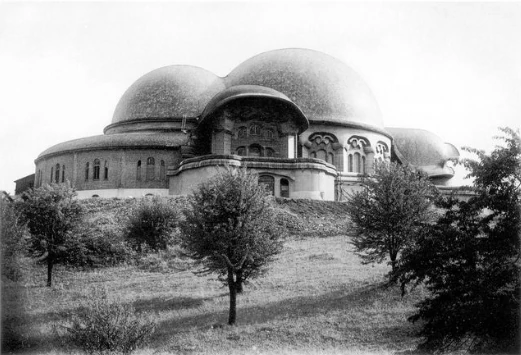

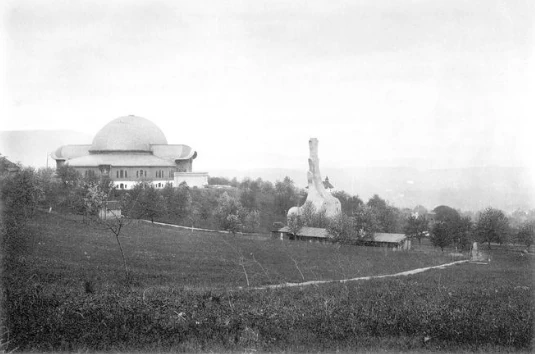

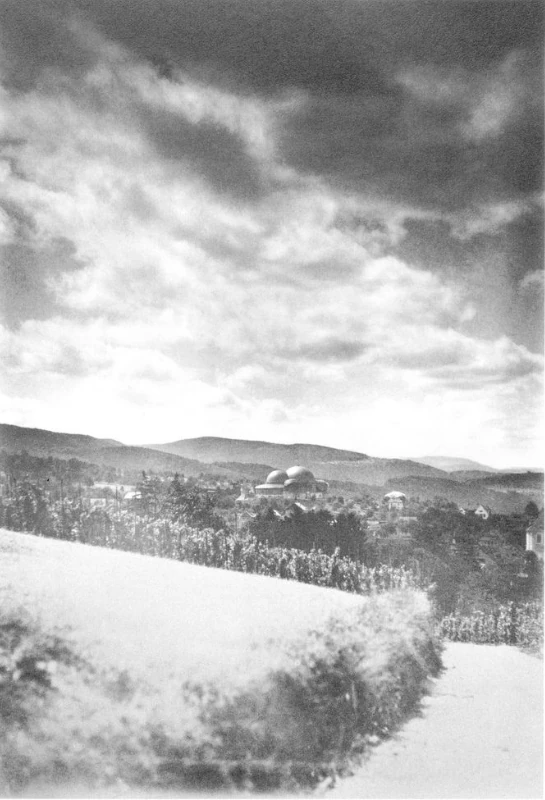

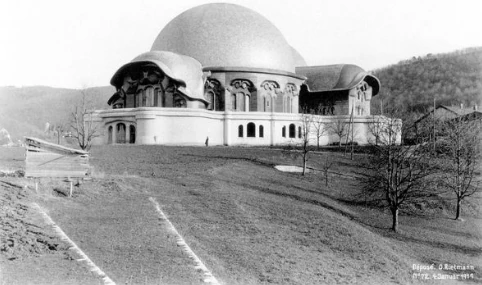

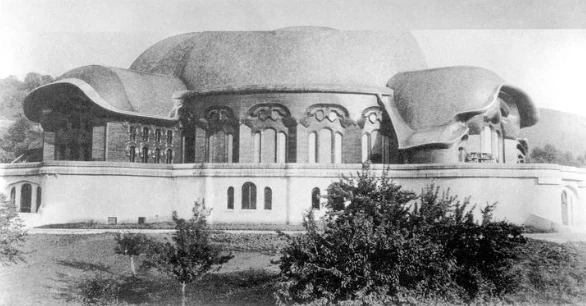

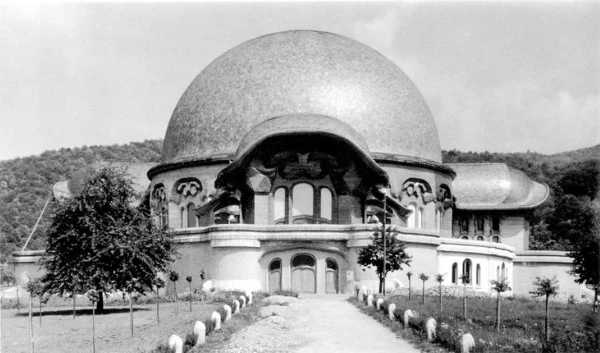

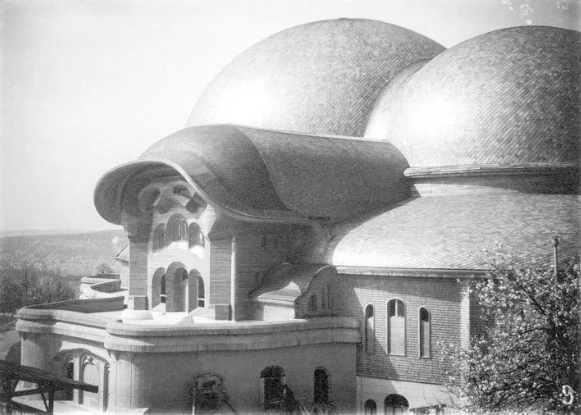

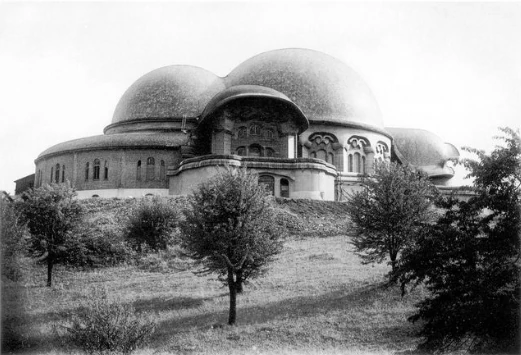

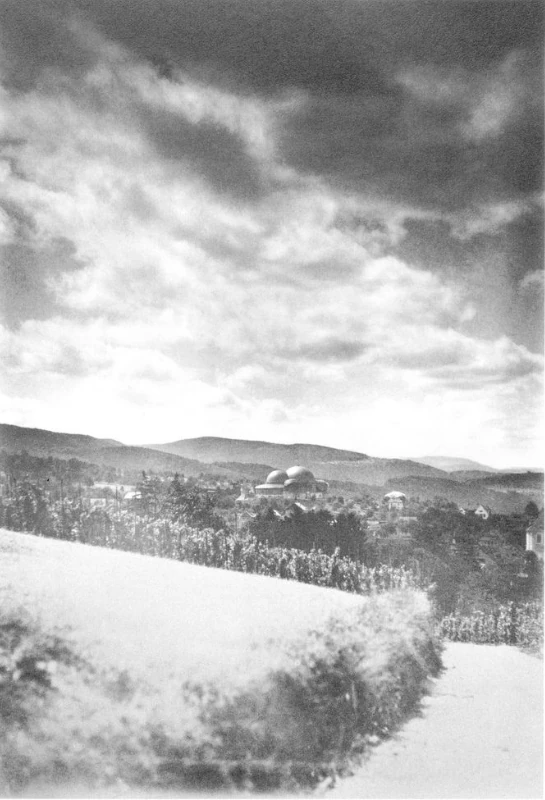

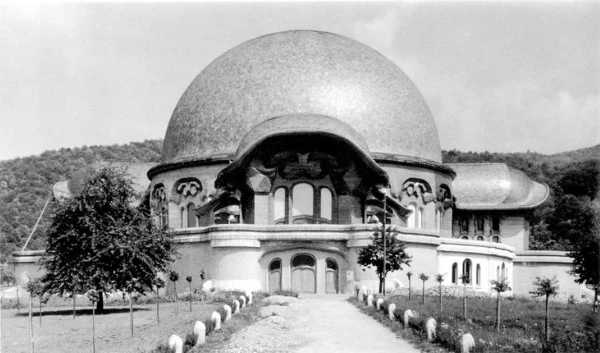

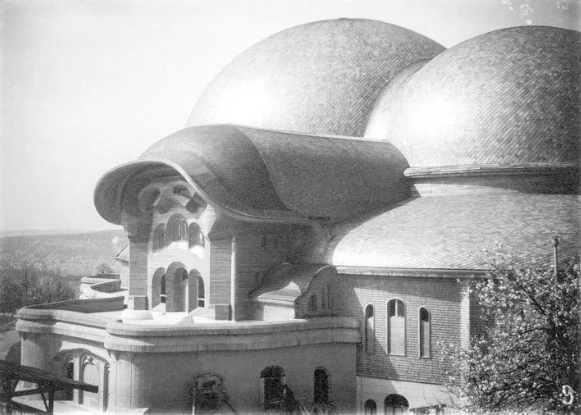

Given that we could not build the structure in Munich due to the narrow-mindedness of the local artistic community, but had to erect it here on the Dornach hill, it must be seen as a stroke of good fortune that, by approaching the hill, this double-domed structure can now really be appreciated. For it is truly not for external reasons that this building has become a double-domed structure. This Goetheanum has become a double-domed structure – a building composed of a larger and a smaller dome – to show that something is to be revealed to contemporary culture and that something is to be received. That which emerges from the depths of spiritual life is represented by the small dome, and the fact of receiving is represented by the large dome. And I think that fate has done well that the one who approaches this hill in Dornach can already have the feeling, through the way in which this double dome rises above the hill, that something new is being added to human development, but something that can also have an effect on human development at the same time. The first pictures we will show you this evening should demonstrate to what extent this is the case.

The first picture we will show is of the building as seen from the north.

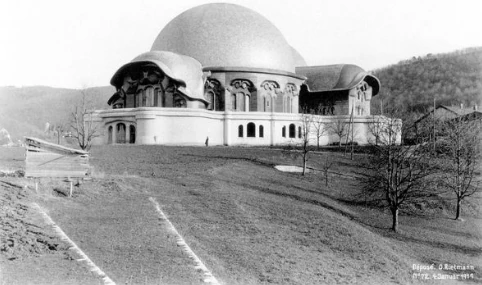

Another aspect. Approached from a slightly different angle, the building looks like this.

The third picture is supposed to show the northeast aspect.

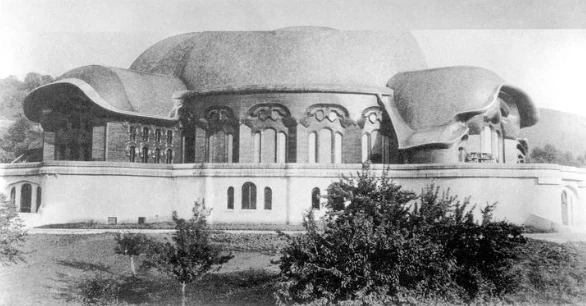

The fourth picture is intended to represent the southwest aspect.

The next picture is supposed to show the northwest aspect.

This is yet another aspect.

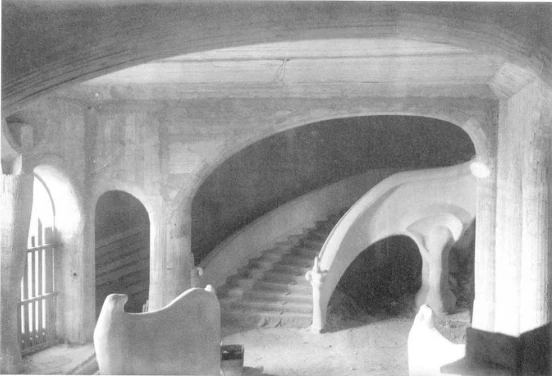

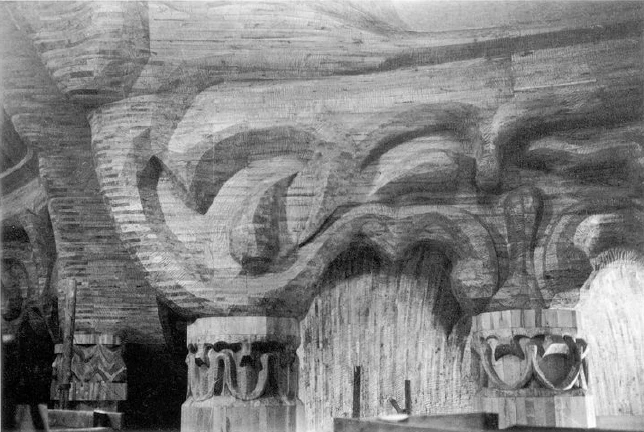

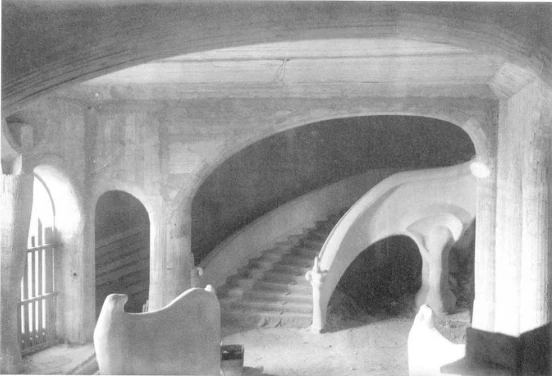

And now let us visualize how the building appears to someone entering from the west. The building is oriented from west to east. You enter at the bottom, and the cloakrooms are downstairs. You come up to the walkway through a stairwell and enter the building through the gates, which are in the west. The whole building is designed in such a way that it presents an organic architectural concept in contrast to the dynamic-mechanical architectural concept to which one is otherwise accustomed. Therefore, the forms everywhere are such that they blend in with the organism of the whole building, just as I would say that any limb – even the smallest in humans, the earlobe – blends in with the whole organism. Thus, a limb blends into the whole organism in such a way that it must be in its place, as it is, as large and as shaped as it is. In the same way, every detail should be in its place in this building; every detail should take its form from the overall form of the building. Furthermore, without falling back on mystical symbolism, there is not a single symbol in the whole building; everything in the building should be poured into artistic forms and show in artistic forms what task each individual piece has.

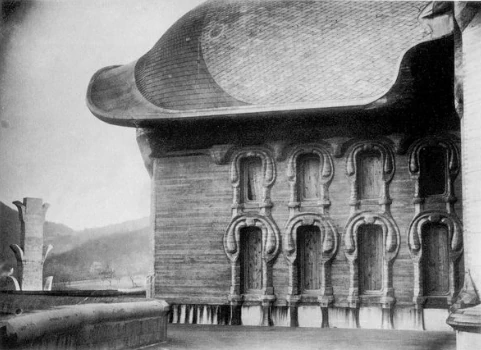

The West Gate. The West Gate has the task of welcoming those who enter. This welcoming, this receiving, this welcoming, so to speak, should be expressed in forms that are not geometric, but which should be expressively organic forms.

As I said, you enter the building from below, via a staircase leading to the gallery, from where you then enter through the west gate.

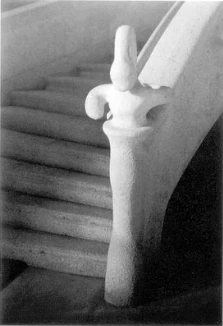

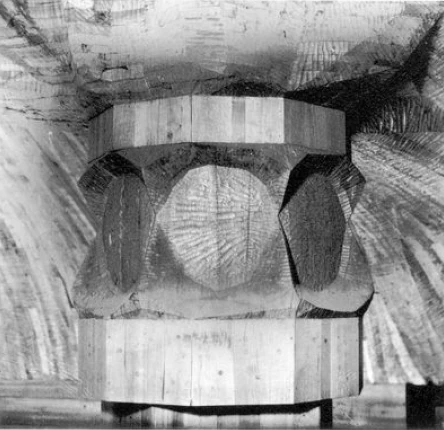

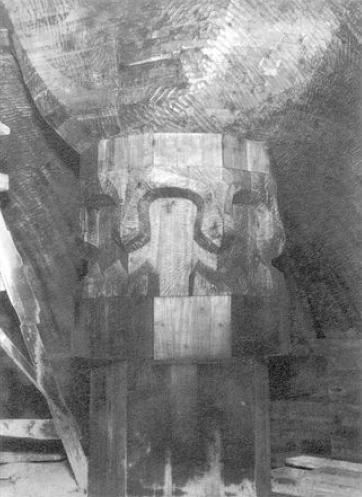

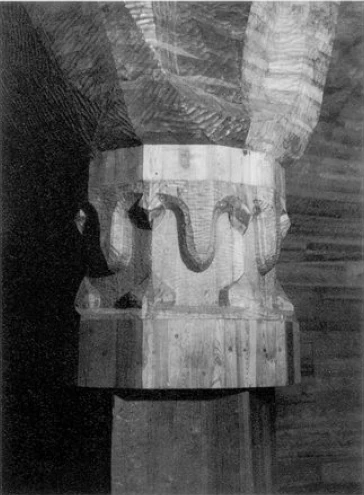

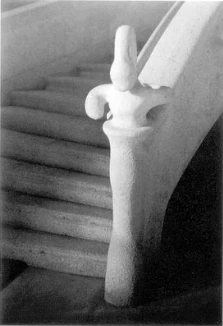

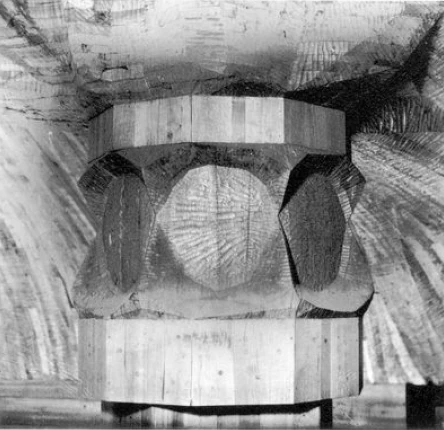

Now the staircase. You are looking here towards the northern side of the staircase. It can be clearly seen from these things how everything here is designed so that it has to be in its place, where it is found. For example, you see how this column capital is perfectly adapted in form to this side, its inclination towards the place where the whole structure must be supported; narrowing on the other side, where the entrance is, where there is nothing more to support.

During on-site explanations, I have often pointed out this structure at the beginning of the staircase: there are three semicircular shapes with their planes perpendicular to each other. It is the shape that emerged in my mind when I tried to imagine how a person walking up these stairs would feel. He would have to feel at the point where the first step of the staircase begins: When I step into it, the external influences of life are calmed. Inner emotional movement will be found inside, which completely calms the outer feeling. In there I will stand on safe ground.

That was what I wanted to express. This presented itself to me because I had to develop this thing here. It is a formation that has an external similarity to the three semi-circular canals in the ear, which, when injured, lead to dizzy spells that thus take away the certainty of the person when they are injured. But that is a discovery that occurred to me only afterwards; the matter itself is formed entirely out of the sensation.

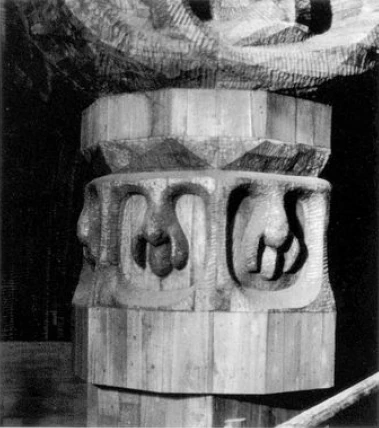

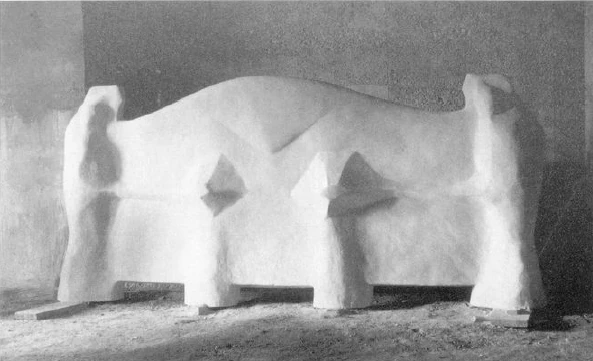

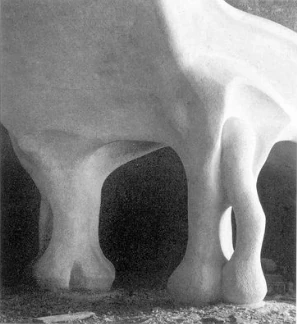

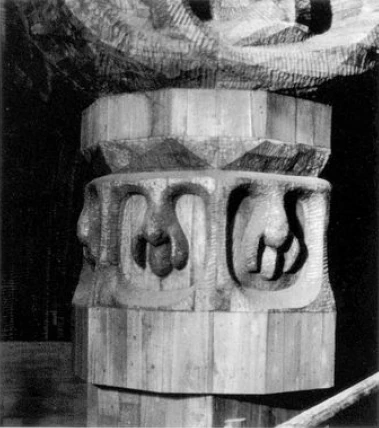

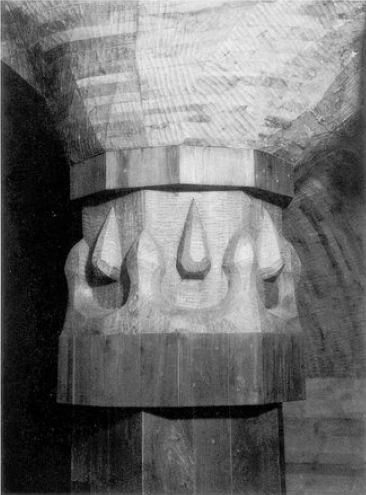

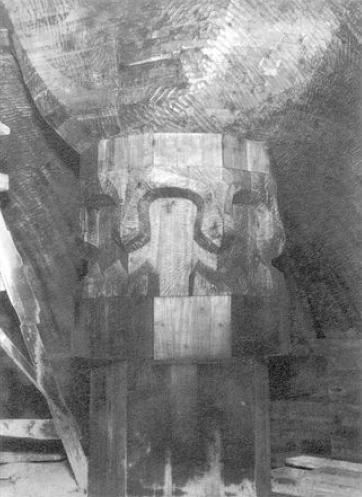

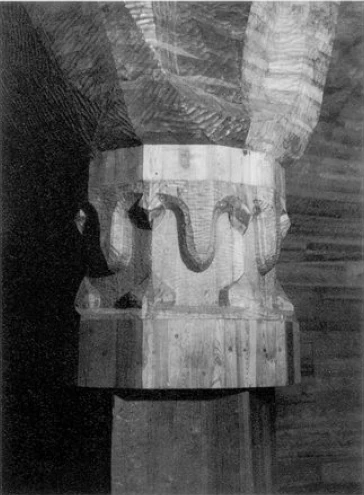

You can also see a radiator cover. These radiator covers are designed in such a way that they represent, on the one hand, growing out of the earth, that is, the forces that grow out of the earth in a supersensible way and permeate the sensible; they are counteracted by other forces coming from above. For those who can perceive this interplay of forces, elemental figures emerge, and these elemental figures are expressed in the forms of these radiator covers, which are otherwise built in their entirety according to Goethe's principle of metamorphosis. Each radiator is the organic metamorphosis of the other. Each was designed to fit exactly into the place in the house where it belongs. But at the same time, the principle of metamorphosis is carried out with the same fidelity as in the plant itself. Every single form, every line, every curve is shaped according to the spatial and functional requirements, and I would say, the original form, which of course is not found here. Every curve is appropriate to the position of the limb of the structure on which the curve is located. A curve that is diverted points to something else in the structure, as opposed to a curve that is bent inward, as you can see here, where the perspective is not even quite right.

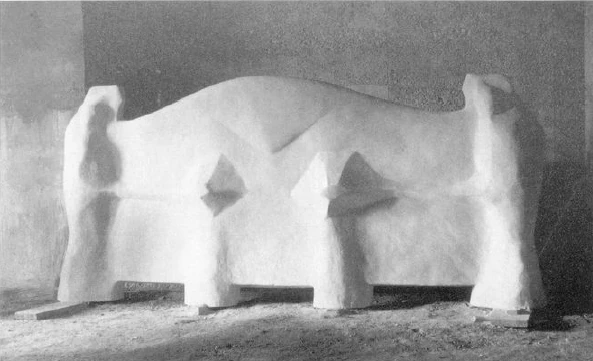

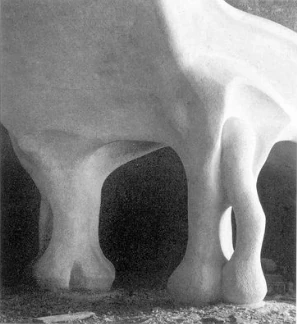

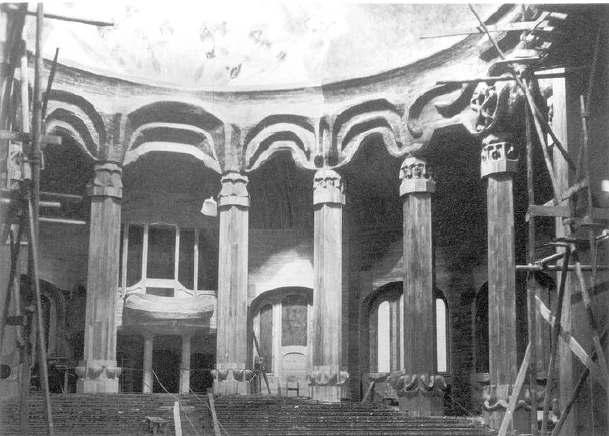

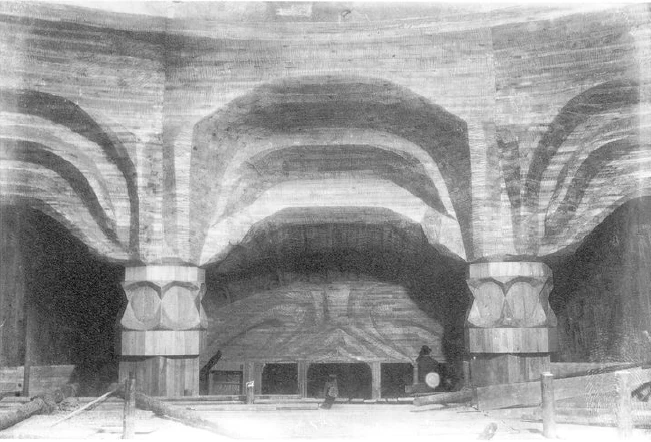

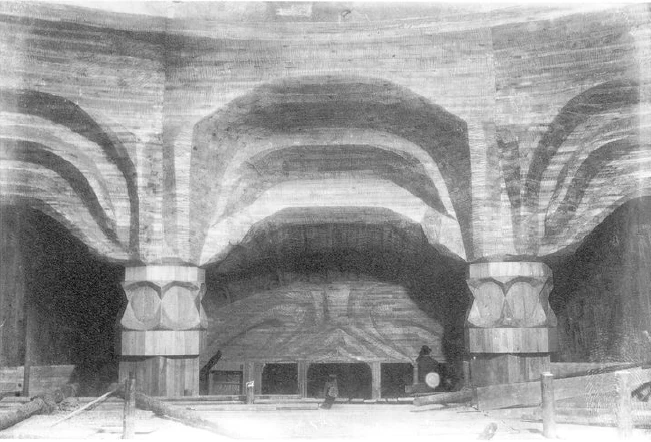

There we saw the same thing again, in more detail. You can see here how an attempt has been made to replace the conventional mathematical-dynamic pillar with something organic, which in its form has the character of support, of support through a force that comes from the elementary forces of the earth and is precisely suited to the distribution of the load that is to be supported at this point in the way in which it shapes its forms. Of course, I am well aware of the many objections that can be raised against such designs from the point of view of traditional architecture. But it is high time that an attempt was made to replace the usual dynamic-mechanical building concepts with an organic building concept that is based not on dynamics and mechanics but on organic principles.

Here we have again seen the side on one side of the main entrance, where you can see how they tried to bring out the character of this being a side piece, how it turns towards the center, how it points to the side. This shaping is particularly important.

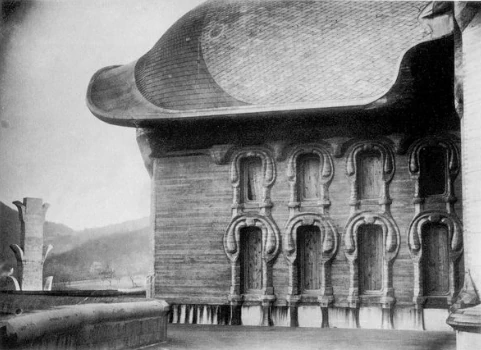

The next picture. Here you can see the side wing, as it goes north, with its windows. And you can see here how it has been tried to overcome the merely decorative. Here, the support is led down everywhere, so that the windows stand up at the bottom, so that not only the windows are worked out of the wall like a decoration, but that the windows stand up everywhere. But you can also see how, in the room containing the motif in question, the same motif that is above the side windows above the main entrance reappears here at these windows. But if you can properly visualize the metamorphosis internally, then such motifs take on such a form that, from a purely external point of view, they no longer resemble other motifs at all, and yet they are actually the same. Just as the sepals and stamens are no different from the petals and leaves of a flower – even though the leaves take on completely different forms depending on the plant's position – so it is here. Thus, Goethe's idea of metamorphosis has been realized in its entirety in the artistic process.

Here we have the upper part of the side entrance. You see, once again, the same motif above, transformed, but also the motifs that you see everywhere, metamorphosed.

Here you see my original model, cut in half, that is, at the point where the axis of symmetry lies. The forms were first worked into this model. This model was, after all, the basis for the construction.

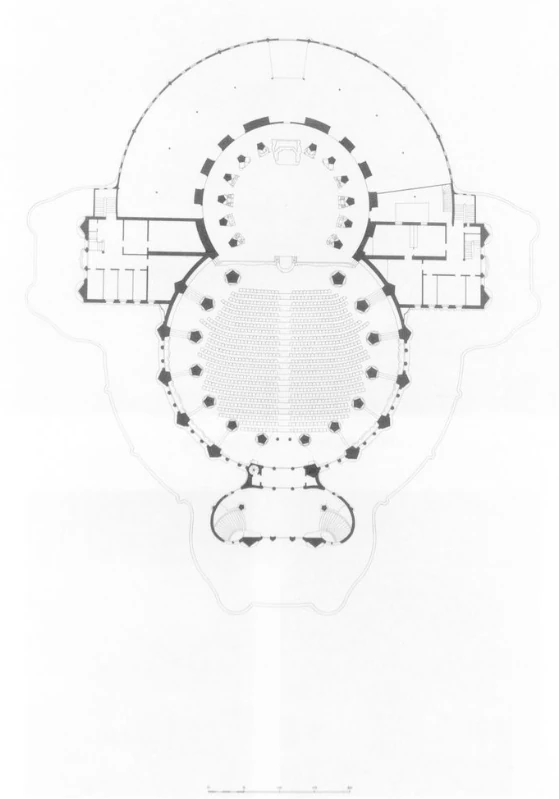

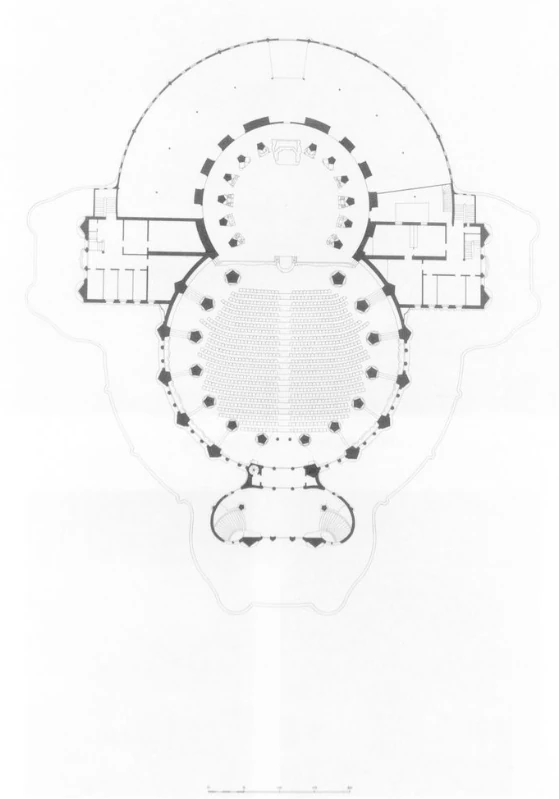

This is the floor plan of the building. This floor plan shows the extent to which the building is designed as a double-domed structure. The small domed room faces east. The main group will stand here, which all of you already know. Here is the west domed room, the auditorium. You can see that when you come in through the entrance, you enter the auditorium. You first come to a vestibule lined with wood, each individual piece of which is handcrafted, and all surfaces and curves are worked so that their surfaces and curves must be exactly where they are.

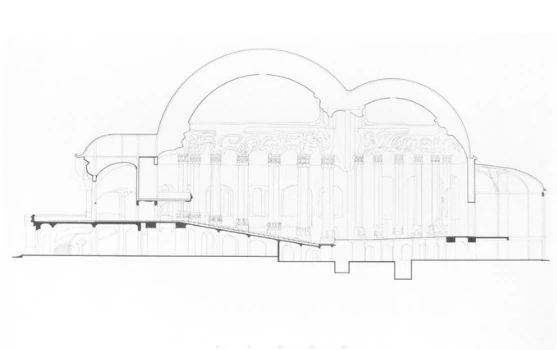

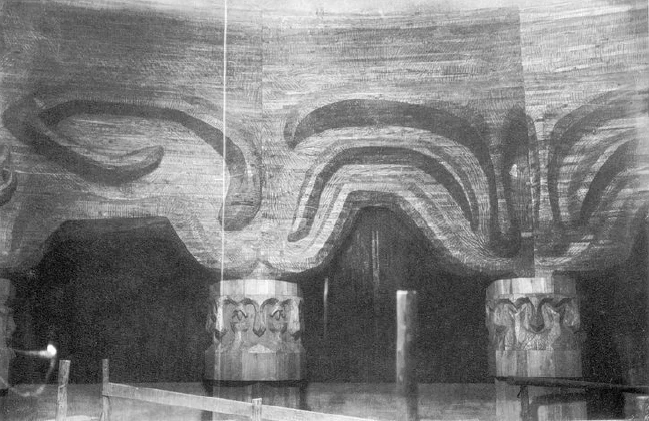

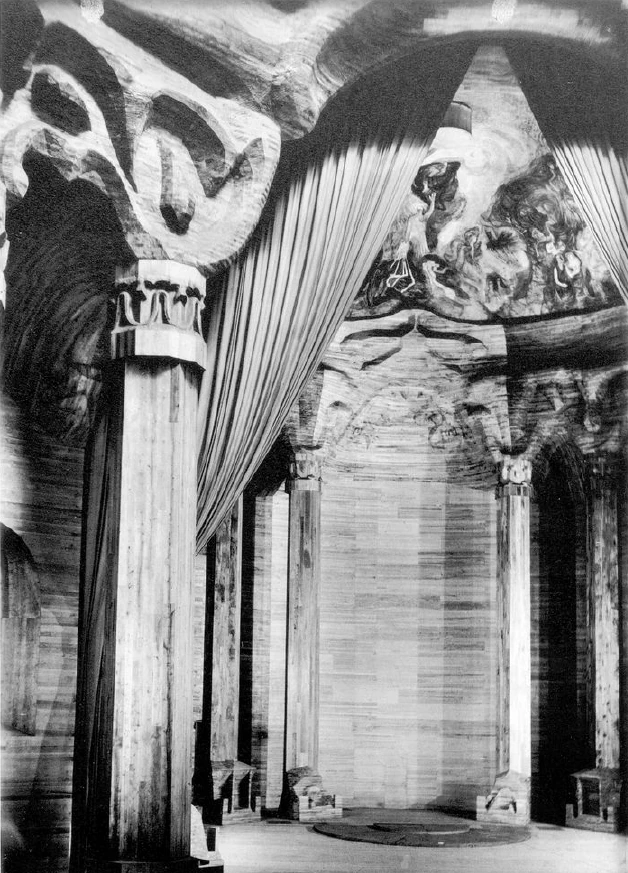

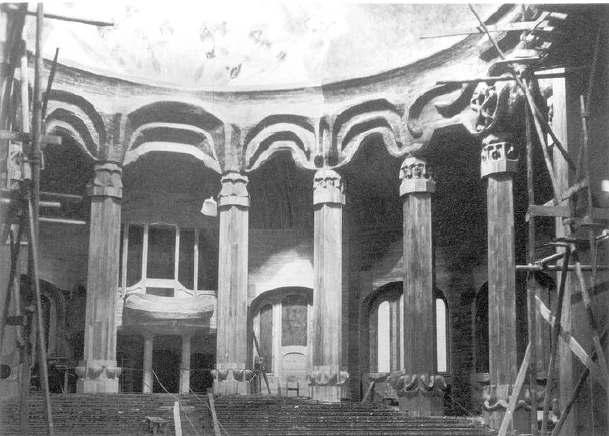

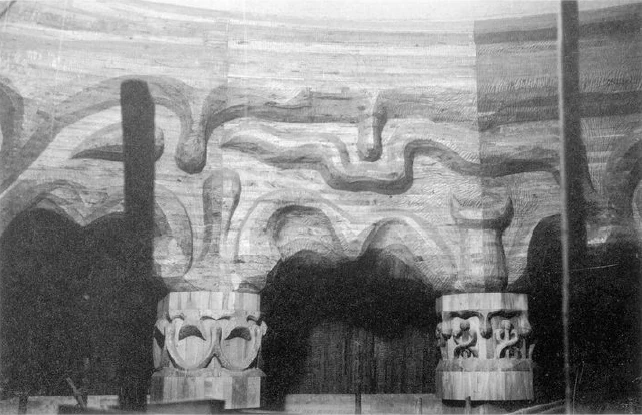

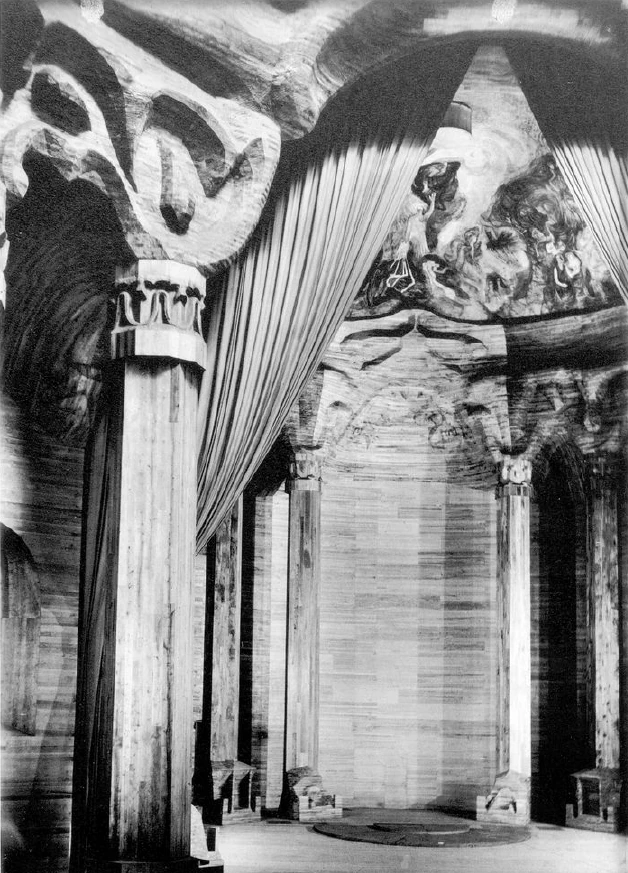

You enter below the organ (Fig. 29). The casing and framing are designed so that you can see that the organ is not just placed in the room, but grows organically out of the entire surroundings of the building. Then you always have a walkway on which you can walk around outside and below during intermissions. The auditorium holds about nine hundred or a thousand people. Then the entire perspective of the building is arranged according to an axis of symmetry; you won't find the same axis of symmetry anywhere else, everything is oriented towards this one axis of symmetry, while otherwise the auditorium is arranged, stepping forward, from seven columns on each side. These columns in the auditorium have bases, have capitals, and above them are architraves. Everything that is worked into these columns is done so in strict accordance with the principle of the evolution of nature itself. If you follow how the capitals, bases and architraves of the individual columns grow out of one another, you will see an image of evolution, of development, in the emergence of one motif from another. It is necessary to immerse oneself in the way in which one form grows out of another in these columns, with artistic devotion, with artistic sensitivity, just as one form of nature's development always grows out of another.

It is not good to start from an abstract terminology in a philistine, pedantic way. There are certain reasons why one can name the one column Saturn's column, the other Venus' column, etc. But one must not obscure what is essential in the essence: the belonging together of the seven columns, the emergence of one column from the other. And above all, we must not obscure what lies in the forms themselves, which must be felt by following the line of swing, the curve of the form, by dreaming ourselves into a symbolism that does not exist. This is more inherent in the emergence of the form of one column from the form of the other column than in simply looking at a column.

In the process, it turned out, by recreating nature itself, so to speak, that the idea of development, which is very often understood as if in each development the following stage of development is always more complicated than the one before, that this idea of development is not correct. Every development proceeds in such a way that at first there is a simple form; then a more complicated one develops from it, then an even more complicated one. This reaches a certain culmination; then again the forms begin to become simpler and simpler, and outwardly the most perfect form reveals itself as the one that has been simplified again. It is only an apparent simplification, but it is still a simplification, I would say, in the limbs, and there is a certain complication in the formation of the limbs. This is strictly adhered to here.

You can see how the design of the columns becomes more complex up to the middle column, and then becomes simpler again towards the east, so that the seventh column is relatively simply designed again.

The small domed room is closed off in this way on each side by six columns, the bases of which are designed to hold twelve seats, and here too the principle of development is fully adhered to for the capitals, the bases, the seats and the architraves. When you endeavor to recreate nature, it is the case that you only truly discover your findings in the finished product that you have created. One can – and this is something that only presented itself to me after the design of the matter in the model – one can, if one takes the raised, convex form of the first column, one can place it in the concave form of the seventh column in a truly artistic way, of course with metamorphosis, but with a true one. The second column fits with its raised part into the concave parts of the sixth column, the third into those of the fifth, and the fourth column stands alone as the central column. Of course, the same principle cannot occur in the same way in the six columns. There, the first and the sixth, the second and the fifth, the third and the fourth really correspond to each other as I have just expressed it. It is something that is found throughout nature, that certain polarities occur, and it was interesting that only the idea of development was retained in the formation of the forms, and that the polarities resulted automatically from the pure retention of the developmental idea.

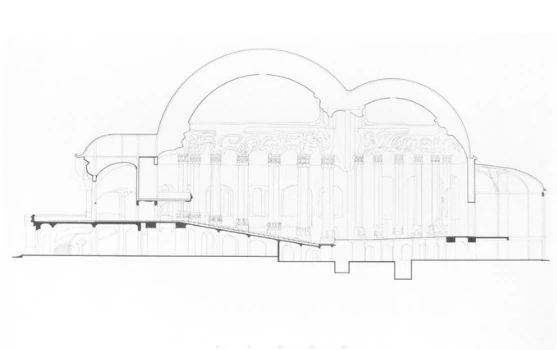

The next picture: Here you have a section through the building in a west-east plane, so that the order of the columns is presented to you exactly as it can be shown in a section.

Here you can see the glass studio in the area below where the windows were cut, which I will talk about later. This glass studio is in some ways a kind of metamorphosis of the whole Goetheanum; only the metamorphosis is brought about by the fact that, firstly, the domes have been pulled apart and a central element has been added, and secondly, the domes have become the same size. For all such inner processes of drawing apart and becoming equally large, metamorphic experiences then arise for the whole organism of a thing. These are then faithfully executed in every detail.

You can also see that the usual geometries in our building have been overcome by the fact that the symmetrical axis has been interrupted to the right and to the left. The idea that each individual piece should be seen in the context of the symmetry of the whole has been applied to the stairs.

You will also see this when you look at the gate for this studio (Fig. 99), with the staircase, the shape of which has been designed in such a way that it really does represent a staircase, precisely because of its shape: you go in, you have a right and a left, while very many stairs that are designed are now really nothing closed, have no right and no left. All these things are to be considered when it comes to a truly artistic creation.

The gate itself is designed in such a way that one recognizes its symmetry as a necessity. When you enter this glass studio, you will also see the lock. It is designed to differ from the usual philistine locks that are otherwise in use and which are really the opposite of anything beautiful.

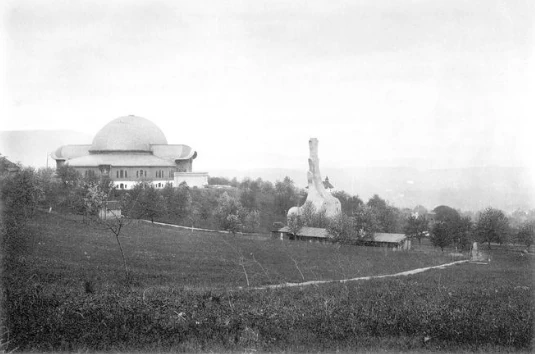

The next picture: Now you see what has been most contested in a certain way, but which will also be understood over time. It is the building in which the heating and lighting are housed, the boiler house. And it is built according to the principle that what is inside has its envelope in the building. Just as a nutshell is shaped so that it is a shell for a nut, here the shell is entirely appropriate for what is inside, right up to the shapes of the chimney, which is only complete when it is smoking, because the smoke is part of these shapes; it then forms the top of the chimney. So everything is conceived according to the same principle by which nature creates when it forms the nutshell around the nut.

We will now turn our attention to the internal motifs. You have used the organ motif here as a model. The architecture around the organ should be such that the whole structure is organically integrated into it, so that one does not have the feeling that the organ has been placed in some random location, but rather that the organ grows out of the whole organization, as it were.

So, by walking through the space below the model and then turning around, we have the two symmetrical columns in the auditorium with the simplest architrave motif at the top. We will now look at each individual column each time.

And as we advance, we first see here the simplest column, one of the two, and now, after we have let its forms act on our perception, we will look at it in connection with the second column.

We shall see how what is simple here [at the first column] grows downwards, how the lower part grows towards it, and how what grows downwards, what grows from top to bottom, undergoes a certain complication of forms, from top to bottom undergoes a certain complication of forms, thereby pushing forward other rising motifs. This can only be felt by observing the succession of the two columns. It is precisely this succession that must be observed.

You can also see here how the architrave motif becomes more complicated. It is actually the case that by immersing yourself in these forms, you can learn more about the idea of development, the developmental principle, the developmental impulse in nature than through any theoretical discussion. Because nature is such that it creates in images, and it must be emphasized again and again that, even if our philosophers prove that one should work with abstractions, with analyses and with the discursive principle to build a science of nature, then nature simply turns its nose up at this science and does not let itself be grasped in this way; it eludes comprehension and leaves us alone with our abstractions. Because it does not create in natural laws, it creates in images.

But now, when we can rise to imaginations in abstract terms, we enter into nature and understand nature's growth. The entire structure should be designed in such a way that it is simultaneously the great hieroglyph through which the world can be grasped. Wherever you look in this structure, you should have a starting point for understanding the world. That is what is, if I may use the term, secretly woven into this structure, that in looking at these forms, that which, so to speak, governs the world at its core, is presented.

We will now see the second pillar on its own.

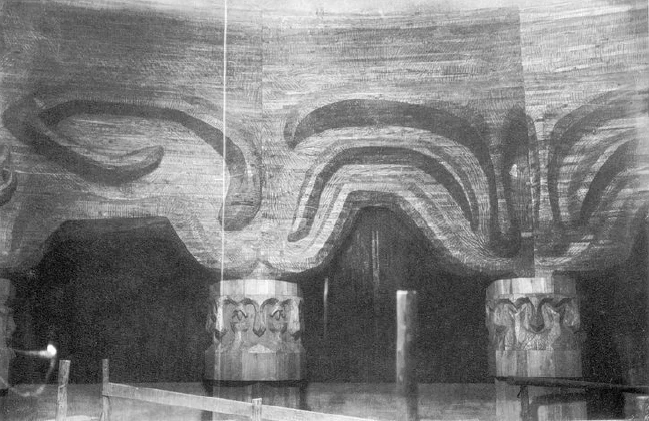

And now again the second with the third column in relation, with the modified architrave motifs. You see how here again the forms become more complicated from top to bottom, and how they are met by forms that become more compact towards the bottom. However, these forms can only be produced, one from the other, if the artistic design is based on the same developmental forces that nature uses to form a plant leaf by leaf, or in a series of developing creatures, one species emerges from the other, one species develops out of the other. By imitating nature, such forms are created. And those who immerse themselves in nature will succeed in recognizing the principle of development in nature. Indeed, something has been set up in this building that should inspire people to say: what surrounds me here as something growing, what surrounds me here as something formed, is something that stands as an explanation of the whole surrounding world.

We will now see the third column on its own.

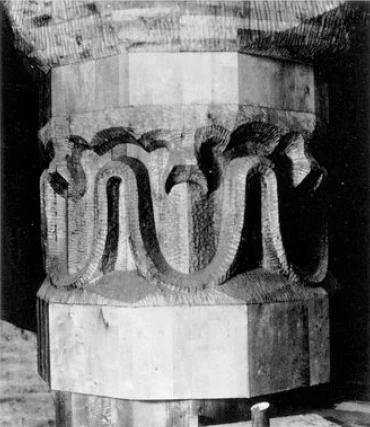

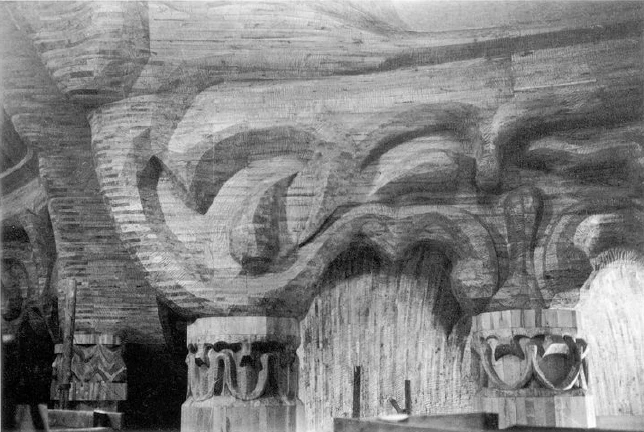

And now we will see the third column in relation to the fourth column again. You can also see that the architrave motifs are becoming more complicated. You just have to imagine how, according to the principle of growth, one emerges from the other, one grows over the other, and you do not need to say: here is a caduceus, but you have a principle of growth that emerges out of it, grows over it, breaks through the overgrowth, and the caduceus does not stand there as an isolated symbol, but as a developmental phenomenon, as a developmental form that emerges from the other. It is the same below with the capital motif.

We will now look at the fourth column on its own.

Now again this column with the following one. You can see how purely by one growing over the other, this caduceus, snake-staff-like structure emerges. It is taken entirely from the growth, not placed as an isolated motif. It is perhaps also cleverer in the usual intellectual sense to throw one motif after the other. That is not what is aimed for here. The aim here is for each motif to emerge from the last, and for the harmony of the motifs to give the actual impression of reality.

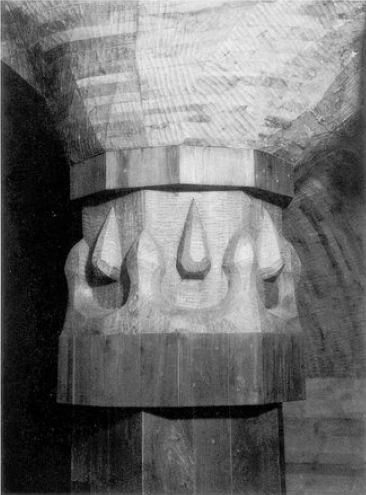

The fifth column on its own.

Now again this column with the next. You can see how here, through the continued growth, not a complication occurs, but a simplification. The architrave motifs have long since become simpler; but here you can see how this motif simply continues to grow, grows upwards, and the motif arises in a completely natural way. In growing, there is always a pushing away. The two parts below here grow upwards; this is rejected, and the motif emerges in a natural way. This is eliminated as it grows; on the other hand, this grows downwards and the shape emerges quite organically from what went before.

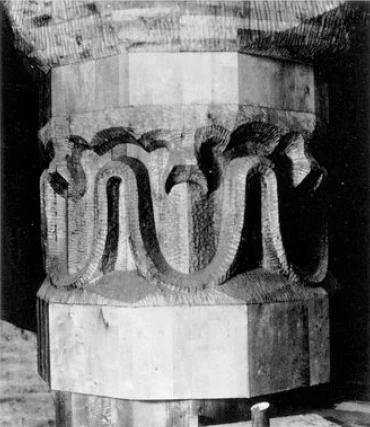

The sixth motif on its own.

And again this motif together with the next one. You can see how the next motif simply emerges from the previous one by growing further, growing, then overgrowing at the top and finally merging.

Now the seventh motif on its own. Another simplification, but a complication in the lines. Tomorrow I will show you this artistic element, which lies in the complication and simplification, by means of a simple representation on the board.

We have now arrived at the point where the curtain column is, where the large dome space merges into the small one. Here you have the last column, the connection between the large and small dome spaces.

We are now moving further into the small domed room. You can see that it goes into the small domed room.

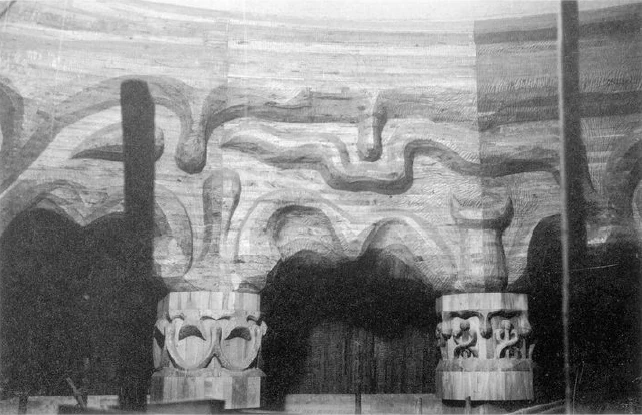

We have here the order of the columns and the architraves of the small domed room. If you remember how the two motifs were on the other columns, you will see that the forms have been changed to reflect the fact that this is a smaller room with only six columns. You just need to consider the following: If you have seven columns that are supposed to create a unified effect, then you have to give each column a different shape. Then imagine circling the same space with six columns instead of seven. In that case, the distances between the columns, which are one and one-seventh, or 8/7, would be different in relation to the previous ones, and so individual shapes would now be changed. And here, in addition, you have the smaller dome space. This further changed the forms. You see, when something like this is created, you get what I would call a sense of space.

Those who think abstractly – and such thoughts have even appeared in scientific literature – are of the opinion that, for example, one can also imagine a human being as very small, atomistically small, that size itself, the spatial volume, has no relationship to the being. But this is not true. Anyone who has immersed themselves in the essence of artistic creation knows that a particular form can only be reproduced in a particular spatial volume, that the size of the space is in an inner relationship to what is being depicted. If you have conceived of some figure for a particular large space, and you then make it en miniature, it seems distressing. But this feeling must be there. The artistic elements must be coordinated with their spatial content to this extent, otherwise they are not truly artistically designed.

The next picture shows another row of columns from the smaller dome with the corresponding architrave. You can see the slit for the curtain, the first column, the second column and so on. We will study the individual columns in their sequence later.

The first column of the small dome.

The next one will now be more complicated, according to the growth principle.

The next one is more complicated again.

Now it is about simplification, but it is a sham simplification; it is simply an outgrowth.

The next column.

There we come to the two columns that border the east end.

We have the carvings of the east end here. You will see them if you look closely. I would say that the forms here can be felt more than seen. If you look closely, you will find that the carving here in the east end encompasses everything that the other forms of the columns and the architraves contain, but of course modified for the vaulting of the room, metamorphosed. Above it a five-petal flower. Anyone who wants to can imagine a pentagram there, but in the same way that one can imagine one in a five-petal plant leaf in nature. A symbolist would have put any old pentagram there. But then one would be acting according to the principle by which we have often acted. Time and again, we have had to experience that artists came to our branch offices who were unpleasantly touched by the fact that unartistic motifs were found everywhere. A cross that was ugly in design, with seven roses around it, was something that was considered more dignified than something truly alive in artistic forms.

It is precisely when one is able to pour the spiritual out completely into artistic forms that what is to be achieved here is achieved: not intrusive symbols, but a shaping in forms in which the spirit lives. When we describe how the Earth developed from Saturn, the Sun and the Moon [gap in the text], we do so in such a way that what lives in the whole also lives in the ideas of our worldview. However, it does not live by expressing itself symbolically through any form, but rather the forms themselves have real inner forces of growth.

Here you can see this eastern end a little more clearly in its individual forms.

The next picture is a detail of the side of the small domed room.

And now, my dear friends, I have begun to use these pictures to explain something about the building to you. I will continue this discussion tomorrow so that those who are hearing it for the first time will get a complete picture of what our building should be from this presentation. I will continue these reflections tomorrow with the help of more slides.

Die Hieroglyphe des Dornacher Baus I

Ich möchte heute aus dem Grunde, weil zu dem Kursus für Mediziner eine Anzahl fremder Persönlichkeiten unter uns sind, noch einmal über das Wesen und die Bedeutung unseres Baues sprechen.

Zunächst habe ich zu bemerken, dass dieser Bau als Repräsentant unserer anthroposophisch orientierten Geisteswissenschaft in seinen Formen, in seinem ganzen Auftreten in der Welt sein soll dasjenige, was nun wirklich auch nach außen hin ein Bild gibt von der Bedeutung und von dem inneren Wesen dieser Bewegung. Man muss sich doch wohl damit bekannt machen, wenn man diese Bewegung in ihrer wahren Bedeutung erkennen will, dass diese Bewegung eintreten will auf den verschiedensten Gebieten des Lebens als etwas völlig Neues, dass ihre Würdigung hervorgehen muss aus der Erkenntnis, dass solches Neues notwendig ist gegenüber der Tatsache, dass alte Impulse in unserer Gegenwart deutlich zeigen, wie sie sich gleich in die Dekadenz bewegen.

Wenn unsere Bewegung nicht hervorgegangen wäre aus demjenigen, was die Zeichen der Zeit selber fordern, aus demjenigen, was nun nicht in irgendeinem Menschheitsprogramm liegt, sondern aus dem, was man ablesen kann an der hinter unserer physischen Menschheitsbewegung liegenden geistigen Entwicklungsströmung dieser Menschheit, auch wenn unsere Bewegung so etwas wäre wie zahlreiche andere Bewegungen, die auch Gesellschaften gründen, die Programme aufstellen, auch sogenannte Ideale aufstellen, dann würde zu einer gewissen Zeit diese Bewegung einen größeren Bau, größere Räumlichkeiten für ihre Mitgliedschaft gebraucht haben, und man hätte sich an irgendeinen Baumeister außen gewendet, um ein Haus bauen zu lassen. Der Baumeister würde nach dem, was hergebrachte Baustile sind - so baut man ja heute —, irgendeinen Bau aufgeführt haben, und es würde die Gesellschaft dasjenige, was sie zu treiben hat, in einem solchen Bau drinnen treiben.

So soll es bei uns nicht sein, sondern, da wir in die Lage kamen, mit einem Bau zu beginnen - der ja vielleicht auch einmal fertig werden wird —, so musste gerade an dieser Tatsache gezeigt werden, wie diese Geistesbewegung auf der einen Seite in die höchsten Höhen des geistigen Lebens steigt, und auf der anderen Seite, wie sie eine gründliche praktische Bewegung ist, die in alle Zweige des praktischen Lebens unmittelbar eingreifen kann. Das heißt, es musste gezeigt werden, dass unsere anthroposophisch orientierte Geistesbewegung imstande ist, neue Bauformen, einen neuen Baustil, aus sich selbst heraus hervorzubringen. Es musste gezeigt werden, dass bis in alle Einzelheiten hinein unsere Bewegung nicht nur eine theoretische Weltanschauungsbewegung darstellt, sondern etwas darstellt, was auch auf alles dasjenige, was äußerlich in die physische Welt sich hineinstellt, seine gestaltende Wirkung haben kann.

So ist dieser Bau nicht gebaut worden als ein äußerlich gleichgültiges Haus, sondern gebaut worden aus der Geisteswissenschaft heraus, aus ihren ureigensten Empfindungen, Ideen, Gedanken heraus, und er ist in allen Einzelheiten ein Abdruck desjenigen, was diese Geisteswissenschaft sein will. Sie will ja nicht eine mystische Schwafelei sein, sie will nicht irgendein abgezogen Theoretisches sein, sondern sie will etwas sein, was tief eingreifen kann auch in das alleralltäglichste Leben, und muss deshalb wohl auch am meisten eingreifen in dasjenige, was ihr eigener Repräsentant sein soll. Im Ganzen dieses Baues sollte ausgedrückt sein, wie er sich in die Gegenwart hineinstellt als ein lebendiger Protest gegen dasjenige, was die Jahrhunderte, die Jahrtausende der Menschheit gebracht haben und was gegenwärtig die Menschheit in den Niedergang geführt hat.

Nachdem die Tatsache gegeben war, dass wir den Bau nicht in München errichten konnten wegen der Borniertheit der dortigen Künstlerschaft, sondern ihn hier auf den Dornacher Hügel aufstellen, da muss es als ein gutes Geschick angesehen werden, dass, indem man sich dem Hügel nähert, nun wirklich auch zur Geltung kommen kann dieser Doppelkuppelbau. Denn wahrhaftig nicht aus äußeren Gründen ist dieser Bau ein Doppelkuppelbau geworden. Dieses Goetheanum ist ein Doppelkuppelbau geworden - ein Bau, der sich zusammensetzt aus einem größeren und einem kleineren Kuppelbau -, um zu zeigen, dass da der gegenwärtigen Kultur etwas geoffenbart werden soll und dass etwas entgegengenommen werden soll. Das aus den Tiefen des Geisteslebens Hervorgehende wird repräsentiert durch den kleinen Kuppelbau, und die Tatsache des Entgegennehmens wird repräsentiert durch den großen Kuppelbau. Und ich denke, das Schicksal hat es gut gemacht, dass derjenige, der sich annähert diesem Dornacher Hügel, schon durch die Art und Weise, wie dieser Doppelkuppelbau sich über dem Dornacher Hügel erhebt, die Empfindung haben kann: Da soll etwas Neues in die Menschheitsentwicklung hineingestellt werden, aber etwas, das zu gleicher Zeit in diese Menschheitsentwicklung hineinwirken kann. Inwiefern dieses sein kann, das sollen uns heute abend die ersten Bilder zeigen, die wir Ihnen vorführen werden.

Das erste Bild, das wir einschalten werden, soll zeigen, wie sich der Bau repräsentiert, wenn man sich ihm von Norden her annähert.

Ein anderer Aspekt. Von einer etwas anderen Stelle genähert, stellt sich der Bau so dar.

Das dritte Bild soll den Nordost-Aspekt darstellen.

Das vierte Bild soll darstellen den Südwest-Aspekt.

Das nächste Bild soll darstellen den Nordwest-Aspekt.

Das ist noch ein anderer Aspekt.

Und nun wollen wir uns vor Augen führen, wie der Bau sich demjenigen repräsentiert, der ihn von Westen her betritt. Der Bau ist orientiert von Westen nach Osten. Man geht unten hinein, und unten sind die Garderobenräume. Man kommt durch ein Treppenhaus nach oben auf den Umgang und geht durch die Tore, die im Westen sind, in den Bau hinein. Der ganze Bau stellt sich so dar, dass er einen organischen Baugedanken darbietet im Gegensatze zu dem dynamisch-mechanischen Baugedanken, an den man sonst gewöhnt ist. Daher sind die Formen überall so, dass sie sich einfügen dem Organismus des ganzen Baues wie sich einfügt, ich möchte sagen, irgendein Glied - und sei es das kleinste beim Menschen, das Ohrläppchen - dem ganzen Organismus. So fügt sich ein Glied dem ganzen Organismus ein, dass es an seiner Stelle so sein muss, wie es ist, so groß und so gestaltet, wie es ist. So soll auch an diesem Bau jede Einzelheit an ihrer Stelle stehen, so soll jede Einzelheit ihre Gestalt aus der ganzen Gestalt des Baues heraus haben. Es soll außerdem, ohne in eine mystische Symbolik zu verfallen - an dem ganzen Bau ist kein einziges Symbolum, alles an dem Bau in künstlerische Formen ausgegossen sein und in künstlerischen Formen zeigen, was irgendeinem Einzelstück für eine Aufgabe zukomme.

Das Westtor. Dem Westtor kommt die Aufgabe zu, denjenigen, der hineingeht, aufzunehmen. Dieses Aufnehmen, dieses Entgegennehmen, dieses gewissermaßen Begrüßen, das soll in den Formen, die nicht geometrische Formen sind, sondern die sprechend organische Formen sein sollen, zum Ausdruck kommen.

Betritt man dann von unten den Bau, so sagte ich schon: Man geht über eine Treppe nach dem Umgang, von dem aus man dann durchs Westtor eintritt.

Nun das Treppenhaus. Sie sehen hier gegen die Nordseite zu den Treppenaufgang. Es ist ja an diesen Dingen so recht zu sehen, wie alles hier so gestaltet ist, dass es eben an seinem Orte, an dem es sich vorfindet, so sein muss. Sie sehen zum Beispiel dieses Säulenkapitell ganz angepasst in seiner Form auf dieser Seite, seiner Hinneigung zu jener Stelle, wo der ganze Bau getragen werden muss; nach der anderen Seite eben sich verengend, wo der Eingang ist, wo also nichts mehr zu tragen ist.

Bei Erklärungen, die an Ort und Stelle vorgenommen werden, habe ich öfters hingewiesen auf dieses Gebilde, das am Anfang der Treppe ist: Es sind drei in ihren Ebenen senkrecht aufeinander stehende Halbkreisformen. Es ist diejenige Form, die sich mir empfindungsgemäß ergeben hat, als sich mir aufdrängte, wie fühlen müsste ein Mensch, der über diese Treppe hinaufgeht. Er müsste an der Stelle, wo die erste Stufe der Treppe beginnt, fühlen: Wenn ich da hineintrete, so werden die äußeren Einwirkungen des Lebens beruhigt. Innere seelische Bewegung wird drinnen zu finden sein, die vollständig beruhigt das äußere Gefühl. Da drinnen werde ich auf sicherem Boden stehen.

Das war auszudrücken. Das bot sich mir, indem ich diese Sache hier ausbilden musste. Es ist ein Gebilde, das in einer Weise eine äußere Ähnlichkeit hat mit den drei halb-zirkelförmigen kleinen Kanälen im Ohre, die, wenn sie verletzt werden, zu Schwindelanfällen führen, die also die Sicherheit aus dem Menschen herausnehmen, wenn sie verletzt sind. Aber das ist eine Entdeckung, die mir erst nachher eingefallen ist; die Sache selbst ist durchaus aus der Empfindung heraus geformt,

Sie sehen da auch einen Heizkörpervorsetzer. Diese Heizkörpervorsetzer sind so gestaltet, dass sie gewissermaßen darstellen auf der einen Seite das Herauswachsen aus der Erde, also die Kräfte, die übersinnlich aus der Erde hervorwachsen und das Sinnliche eben durchkraften; ihnen wirken entgegen von oben herunter andere Kräfte. Für den, der dieses Wechselspiel der Kräfte wahrnehmen kann, stellen sich hinein Elementarwesengestalten, und diese Elementarwesengestalten, die sind in den Formen hier dieser Heizkörpervorsetzer zum Ausdruck gekommen, die außerdem in ihrer Gänze nach dem’ Goethe’schen Metamorphösenprinzip gebaut sind. Jeder Heizkörper ist die organische Metamorphose des anderen. Jeder ist so entstanden, dass er genau an diejenige Stelle des Hauses, an die er hin muss, hinpasst. Aber es ist zu gleicher Zeit das Prinzip der Metamorphose in solcher Treue durchgeführt wie an der Pflanze selber. Jede einzelne Form, jede Linie, jeder Schwung ist gemäß der Raumanforderung und der Zweckanforderung aus, ich möchte sagen, der Urgestalt, die natürlich sich hier nicht findet, herausgebildet. Jede Kurve ist angemessen der Lage des Gliedes des Baues, an dem sich die Kurve befindet. Eine Ausschweifung der Kurve ist auf etwas anderes im Bau weisend als eine Einbeugung der Kurve, wie Sie hier, wo die Perspektive nicht einmal ganz richtig die Sache ergibt, ersehen können.

Da haben wir dasselbe, mehr im Detail wiederum gesehen. Sie sehen hier, wie versucht worden ist, den gewöhnlichen mathematisch-dynamischen Pfeiler zu ersetzen durch etwas Organisches, das in seiner Form den Charakter des Tragens hat, des Tragens durch eine Kraft, die aus den Elementarkräften der Erde herauskommt und eben in der Art, wie sie ihre Formen gestaltet, gerade jener Verteilung von Last angemessen ist, die an dieser Stelle zu stützen ist. Ich weiß natürlich sehr gut, wie viel eingewendet werden kann gegen solche Gestaltungen vom Standpunkte der hergebrachten Architektur. Allein es sollte eben einmal der Versuch gemacht werden, die gewöhnlichen dynamisch-mechanischen Baugedanken zu ersetzen durch einen organischen Baugedanken, der herausgenommen ist aus dem Prinzip nicht der Dynamik und der Mechanik, sondern der Organik.

Hier haben wir wiederum zur Seite hin gesehen auf der einen Seite des Haupteinganges, wo Sie sehen können, wie man sich bemüht hat, diesen Charakter herauszubekommen, dass das eben ein Seitenstück ist, wie es gegen die Mitte hin zu sich wendet, wie es nach der Seite hin weist. Auf diese Formung kommt es ganz besonders an.

Das nächste Bild. Hier sehen Sie dann den Seitenflügel, wie er nach Norden geht, mit seinen Fenstern. Und Sie sehen hier, wie versucht worden ist, das bloß Dekorative zu überwinden. Es ist hier überall die Stütze bis hinunter geführt, sodass die Fenster am Boden aufstehen, dass nicht bloß die Fenster wie eine Dekoration herausgearbeitet sind aus der Wand, sondern dass die Fenster überall aufstehen. Sie sehen aber außerdem, wie hier in dem Raum, in dem das betreffende Motiv ist, dasselbe Motiv, das über den Seitenfenstern über dem Haupteingang ist, hier an diesen Fenstern wieder erscheint. Aber wenn man richtig die Metamorphose innerlich gestalten kann, dann nehmen solche Motive solche Gestalt an, dass sie, rein äußerlich gesehen, anderen Motiven gar nicht mehr ähnlich sind, und doch eigentlich dasselbe sind. So wie das Kelchblatt, die Staubgefäße, auch nichts anderes sind als das Blumenblatt und das Laubblatt - wenn auch die Blätter ganz anders gestaltet sind, je nach dem einen oder anderen Standort der Pflanze, so ist es hier mit diesem. Es ist also der Goethe’sche Metamorphosegedanke ins Künstlerische umgestaltet in der ganzen Durchführung zur Geltung gekommen.

Da haben wir das Obere des Seiteneinganges. Sie sehen wiederum verändert, in Metamorphose, dasselbe Motiv oben; aber auch sonst die Motive, die Sie überall sehen, metamorphosisch verändert.

Hier sehen Sie mein ursprüngliches Modell, durchschnitten in der Mitte, also an derjenigen Stelle durchschnitten, wo die Symmetrieachse liegt. In dieses Modell wurden zuerst die Formen hineingearbeitet. Dieses Modell hat ja zuerst dem Bau zugrunde gelegen.

Sie sehen hier den Grundriss des Baues. Dieser Grundriss, er zeigt Ihnen, inwiefern der Bau als ein Doppelkuppelbau gedacht ist. Der kleine Kuppelraum ist nach Osten hin orientiert. Hier wird die Hauptgruppe stehen, die ja alle von Ihnen bereits kennen. Hier ist der Westkuppelraum, der Zuschauerraum. Sie sehen, wenn man durch den Eingang hereinkommt, betritt man den Zuschauerraum. Man kommt zuerst in eine Vorhalle, die mit Holz ausgekleidet ist und bei der alles Einzelne in der Holzumkleidung ja zuletzt mit der Hand gearbeitet ist, und alle Flächen und Kurven so gearbeitet sind, dass ihre Flächen und Kurven genau an der Stelle sein müssen, an der sie sind.

Man tritt ein unter der Orgel (Abb. 29). Auch die Umkleidung, die Umrahmung ist so gedacht, dass man sieht: Die Orgel ist nicht bloß in den Raum gestellt, sondern wächst organisch aus der ganzen Umgebung des Baues heraus. Dann hat man immer wiederum einen Umgang, auf dem man herumgehen kann in Zwischenpausen außen, wie unten. Der Zuschauerraum fasst ungefähr neunhundert oder tausend Menschen. Dann ist die ganze Perspektive des Baues nach einer Symmetrieachse angeordnet; eine gleiche Symmerrieachse finden Sie woanders nicht, es ist alles nur auf diese eine Symmetrieachse hin orientiert, während ansonsten eine Anordnung im Zuschauerraum ist, nach vorwärts schreitend, von sieben Säulen auf jeder Seite. Diese Säulen im Zuschauerraum haben Sockel, haben Kapitelle, und über ihnen sind Architrave. Alles dasjenige, was da in diese Säulen hineingearbeitet ist, ist streng nach dem Prinzip der Evolution der Natur selber gearbeitet. Wenn Sie verfolgen, wie Kapitelle, Sockel- und Architravüberwölbung der einzelnen Säulen, eines aus dem anderen hervorwächst, so werden Sie ein Abbild des Evolvierens, des sich Entwickelns, in dem Entstehen des einen Motivs aus dem anderen sehen. Es ist schon notwendig, dass man gerade mit künstlerischer Hingabe, mit künstlerisch empfindender Hingabe sich versenkt in die Art und Weise, wie die eine Form aus der anderen gerade bei diesen Säulen herauswächst, so wie eben immer eine Entwicklungsform der Natur aus der anderen herauswächst.

Es ist nicht gut, wenn man in philiströs pedantischer Weise von einer abstrakten Terminologie ausgeht. Nicht wahr, es gibt ja gewisse Gründe, warum man hier die eine Säule nennen kann Saturnsäule, die andere Venussäule usw. Aber man darf nicht überdecken durch diese Benennung und durch diese abstrakte Symbolik dasjenige, worauf es im Wesen ankommt: die Zusammengehörigkeit der sieben Säulen, das Hervorgehen der einen Säule aus der anderen. Und vor allen Dingen darf man nicht überdecken dadurch, dass man sich in eine gar nicht bestehende Symbolik hineinträumt, dasjenige, was in den Formen selber liegt, was durchaus gefühlt werden muss, indem man die Schwunglinie, die Kurve der Form verfolgt. Die ist mehr gelegen in dem Hervorgehen der Form der einen Säule aus der Form der anderen Säule als in dem bloßen Hinschauen auf eine Säule.

Dabei stellte es sich noch heraus, indem man gewissermaßen die Natur selber nachschuf, dass jener Entwicklungsgedanke, der sehr häufig so aufgefasst wird, als ob bei jeder Entwicklung immer das folgende Entwicklungsstadium ein komplizierteres wäre als das vorhergehende, dass dieser Entwicklungsgedanke nicht richtig ist. Jede Entwicklung geht so vor sich, dass zunächst die einfache Form dasteht; dann entwickelt sich daraus eine kompliziertere, dann eine noch kompliziertere. Das erreicht eine gewisse Kulmination; dann wiederum beginnen die Formen einfacher und einfacher zu werden, und nach außen hin offenbart sich die vollkommenste Form als die wiederum vereinfachte. Es ist das nur eine scheinbare Vereinfachung, aber es ist doch eben eine Vereinfachung, ich möchte sagen, in den Gliedern, und es ist eine gewisse Komplikation in der Formung der Glieder. Das ist hier streng eingehalten.

Sie sehen die Komplikation der Säulengestaltung bis zur mittleren Säule komplizierter werden, und dann wiederum gegen Osten hin einfacher werden, sodass die siebente Säule wieder verhältnismäßig einfach gestaltet ist.

Der kleine Kuppelraum ist in der Weise abgeschlossen auf jeder Seite durch sechs Säulen, deren Sockel ausgestaltet sind zu zwölf Sitzen, und auch hier ist das Prinzip der Entwicklung bei den Sockeln, sogar für die Sitze, für die Kapitelle, für die Architrave durchaus festgehalten. Es ist, wenn man sich bemüht, der Natur nachzuschaffen, so, dass man in der Tat an dem Fertigen, das man dann gestaltet hat, gewissermaßen seine Entdeckungen erst macht. Man kann - und das ist etwas, was sich mir erst nach der Ausgestaltung der Sache im Modell dargeboten hat -, man kann, wenn man von der ersten Säule die erhabene, konvexe Form nimmt, man kann sie in die konkave Form der siebenten Säule richtig künstlerisch hineinlegen, natürlich mit Metamorphose, aber mit einer richtigen. Die zweite Säule passt mit ihrem erhabenen Teil in die konkaven Teile der sechsten Säule, die dritte in die der fünften, und die vierte Säule steht als mittlere Säule für sich allein da. Dasselbe Prinzip kann selbstverständlich nicht in derselben Weise auftreten bei den sechs Säulen. Da ist wirklich die erste und die sechste, die zweite und die fünfte, die dritte und die vierte einander so entsprechend, wie ich es jetzt eben ausgesprochen habe. Das ist etwas, was in der ganzen Natur sich findet, dass da gewisse Polaritäten auftreten, und es war interessant, dass da nur der Entwicklungsgedanke festgehalten worden ist in der Gestaltung der Formen und dass sich da durch das reine Festhalten des Entwicklungsgedankens von selbst die Polaritäten ergeben haben.

Das nächste Bild: Da haben Sie einen Schnitt geführt durch den Bau in der West-OstEbene, sodass sich Ihnen darstellt die Säulenordnung eben so, wie sie sich aus einem Schnitt darstellen kann.

Hier haben Sie noch einen Blick auf das Glasatelier unten in der Umgebung des Baues, in dem die Fenster geschliffen worden sind, über die ich noch zu reden haben werde. Dieses Glasatelier ist in gewisser Weise eine Art Metamorphose des ganzen Goetheanums; nur ist die Metamorphose dadurch bewirkt, dass erstens die Kuppeln auseinandergezogen sind und ein Mittelglied da ist, und dass zweitens die Kuppeln gleich groß geworden sind. Für alle solchen inneren Vorgänge des Auseinanderziehens, des Gleichgroßwerdens ergeben sich dann für den ganzen Organismus einer Sache metamorphosische Erfahrungen. Die sind dann getreulich zur Ausführung gebracht in allem Einzelnen.

Sie sehen auch, dass die gewöhnlichen Geometrien bei uns im Bau überwunden sind dadurch, dass immer auf die symmetrische Achse nach rechts und nach links zäsiert worden ist. Bis zu den Treppen ist festgehalten, dass jedes einzelne Stück aus der Symmetrie des Ganzen heraus ins Auge gefasst werden soll.

Das werden Sie auch sehen, wenn Sie das Tor für dieses Atelier ins Auge fassen (Abb. 99), mit der Treppe, deren Form eben so gesucht worden ist, dass sie wirklich eine Treppe darstellt, eben durch ihre Gestalt, dass sie darstellt: Da geht man hinein, hat ein Rechts und ein Links, während sehr viele Treppen, die gestaltet werden, nun wirklich nichts Abgeschlossenes sind, kein Rechts und kein Links haben. Alle diese Dinge sind zu berücksichtigen, wenn es sich um eine wirklich künstlerische Schöpfung handelt.

Das Tor selbst ist so gestaltet, dass man seine Symmetrie als eine notwendige begreift. Wenn Sie in dieses Glasatelier hineingehen, werden Sie auch das Schloss sehen. Das ist so gedacht, dass es abweicht von den gewöhnlichen Philisterschlössern, die da sonst in Gebrauch sind und die eigentlich nun wirklich das Gegenteil von allem Schönen darstellen.

Das nächste Bild: Nun sehen Sie das, was in einer gewissen Weise am allermeisten angefochten worden ist, was man aber auch mit der Zeit schon verstehen wird. Es ist derjenige Bau, in dem die Beheizung und Beleuchtung untergebracht worden ist, das Kesselhaus. Und es ist so richtig gebaut nach dem Prinzip, dass dasjenige, was darinnen ist, seine Umhüllung hat durch den Bau. Wie die Nussschale so gestaltet worden ist, dass sie eben Schale der Nuss ist, so ist hier dasjenige, was umhüllt, ganz angemessen dem, was drinnen ist, bis hinauf zu diesen Formen des Schornsteines, der erst ganz vollkommen ist, wenn er raucht, denn der Rauch gehört dazu zu diesen Formen; er gibt ihnen dann nach oben den Abschluss. So ist alles ja gedacht nach demselben Prinzip, nach welchem die Natur schafft, wenn sie um die Nuss herum die Nussschale formt.

Wir werden nun unsere Betrachtungen den inneren Motiven zuwenden. Sie haben hier das Orgelmotiv, nach dem Modell genommen. Die Architektur um die Orgel herum sollte durchaus so sein, dass das Ganze im Bau organisch drinnensteht, dass man nicht das Gefühl hat, die Orgel ist an irgendeinen Ort hingesetzt, sondern die Orgel wächst gleichsam aus der ganzen Organisation heraus.

Da haben wir nun, indem wir den Raum unterhalb des Modells durchgehen und uns dann umwenden, die zwei symmetrischen Säulen, die im Zuschauerraum sind, mit dem einfachsten Architravmotiv oben. Wir werden uns nun jedes Mal jede einzelne Säule ansehen.

Und indem wir vorrücken, sehen wir zunächst hier die einfachste Säule, eine von den zweien, und jetzt werden wir sie dann, nachdem wir ihre Formen auf unsere Empfindung haben wirken lassen, im Zusammenhang mit der zweiten Säule uns ansehen.

Wir werden sehen, wie dasjenige, was hier [bei der ersten Säule] einfach ist, herunterwächst, wie ihm das Untere entgegenwächst, und wie dann das, was herunterwächst, was von oben nach unten wächst, eine gewisse Komplikation der Formen erlebt, von oben nach unten eine gewisse Komplikation der Formen erlebt, dadurch wiederum nachschiebend andere aufgehende Motive. Das kann man nur empfinden, wenn man die Aufeinanderfolge der zwei Säulen ins Auge fasst. Gerade dieses, die Aufeinanderfolge, das ist es, was man ins Auge fassen muss.

Ebenso sehen Sie hier das Komplizierterwerden des Architravmotivs. Es ist tatsächlich so, dass man, indem man sich vertieft in diese Formen, mehr über den Entwicklungsgedanken, über das Entwicklungsprinzip, den Entwicklungsimpuls in der Natur lernen kann als durch irgendeine theoretische Auseinandersetzung. Denn die Natur ist eben so, dass sie in Bildern schafft, und es muss immer wieder betont werden, wenn unsere Philosophen auch beweisen, man solle nach Abstraktionen arbeiten, nach Analysen und nach dem diskursiven Prinzip eine Wissenschaft von der Natur aufbauen, dann dreht die Natur dieser Wissenschaft einfach eine Nase, und sie lässt sich so nicht begreifen, sie entzieht sich dem Begreifen, lässt uns mit unseren Abstraktionen allein. Denn sie schafft nicht in Naturgesetzen, sie schafft in Bildern.

Nun aber, wenn wir uns in den abstrakten Begriffen zu Imaginationen erheben können, kommen wir in die Natur hinein, begreifen wir das Wachstum der Natur. Der ganze Bau sollte so gestaltet werden, dass er zu gleicher Zeit die große Hieroglyphe ist, durch die die Welt erfasst werden kann. Wo man hinschaut in diesem Bau, soll man einen Anhaltspunkt haben zum Weltverständnis. Das ist dasjenige, was, wenn ich mich des Terminus bedienen darf, in diesen Bau hineingeheimnisst ist, dass im Angeschauten dieser Formen sich darstellt dasjenige, was die Welt gewissermaßen im Innersten beherrscht.

Wir werden jetzt die zweite Säule für sich allein sehen.

Und jetzt wiederum die zweite mit der dritten Säule in Beziehung, mit den veränderten Architravmotiven. Sie sehen, wie hier wiederum die Formen von oben herunter komplizierter werden, und ihnen unten kompakter werdende Formen entgegenwachsen. Man kann aber diese Formen, eine aus der anderen, nur hervorbringen, wenn man nach denselben entwicklungsgestaltenden Kräften die künstlerische Gestaltung vornimmt, nach denen die Natur Blatt für Blatt an der Pflanze bildet, oder in einer Entwicklungsreihe von Wesen eine Art aus der anderen hervorgeht, eine Art aus der anderen eben heraus sich gestaltet. Durch Nachschaffen der Natur werden solche Formen gebildet. Und wer sich in die Natur hineinversenkt, der erreicht, das Entwicklungsprinzip in der Natur zu erkennen. Es ist in der Tat in diesem Bau etwas hingestellt, was dem Menschen sich so ergeben soll, dass er sagt: Was mich hier umschließt als Wachsendes, was mich hier umgibt als Gestaltetes, das ist etwas, was dasteht wie ein Erklärer der ganzen umliegenden Welt.

Wir werden jetzt die dritte Säule für sich allein sehen.

Und nun werden wir wieder die dritte Säule mit der vierten Säule in Relation sehen. Sie sehen auch zu gleicher Zeit die Architravmotive komplizierter werden. Sie brauchen sich nur vorzustellen, wie nach dem Wachstumsprinzip das eine hier aus dem anderen hervorgeht, das eine das andere überwächst, und Sie haben nicht nötig, zu sagen: Hier ist ein Merkurstab, sondern Sie haben ein Wachstumsprinzip, das geht aus dem hervor, überwächst sich, reißt durch das Überwachsen ab, und der Merkurstab steht nicht als ein isoliertes Symbol da, sondern er steht als Entwicklungserscheinung, als Entwicklungsgestalt da, die aus der anderen hervorgeht. Ebenso ist es unten mit dem Kapitellmotiv.

Wir wollen jetzt die vierte Säule für sich allein ansehen.

Nun wiederum diese Säule mit der folgenden zusammen. Da können Sie sehen, wie rein dadurch, dass das eine das andere überwächst, dieses Merkurstab, Schlangenstab-ähnliche Gebilde hervorgeht. Es ist ganz aus dem Wachstum herausgeholt, nicht als isoliertes Motiv hingesetzt. Es ist ja vielleicht auch im gewöhnlichen intellektualistischen Sinn gescheiter, wenn man ein Motiv nach dem andern so hinwirft. Das ist hier nicht angestrebt. Hier ist das angestrebt, dass Motiv für Motiv, eines aus dem andern hervorgeht, und eigentlich das, was gegeben werden soll, durch den Zusammenklang der Motive gegeben wird.

Die fünfte Säule für sich allein.

Nun wiederum diese Säule mit der nächsten. Sie sehen, wie hier durch das Weiterwachsen nun nicht eine Komplikation eintritt, sondern eine Vereinfachung. Die Architravmotive sind schon längst einfacher geworden; aber hier sehen Sie, wie dieses Motiv einfach weiterwächst, nach oben hinauf wächst, und das Motiv auf ganz naturgemäße Weise entsteht. Beim Wachsen findet ja immer ein Abstoßen statt. Die beiden Teile unten hier, die wachsen herauf; das wird abgestoßen, und es entsteht das Motiv auf naturgemäße Weise. Dies hier fällt weg beim Wachsen; dagegen wächst das herunter und es entsteht diese Form ganz organisch aus dem Vorhergehenden.

Das sechste Motiv für sich allein.

Wiederum dieses Motiv nun mit dem nächsten zusammen. Sie sehen da, wie das nächste einfach durch Weiterwachsen aus dem Vorhergehenden hervorgeht, wächst, dann überwächst oben und schließlich zusammenwächst.

Jetzt das siebente Motiv für sich allein. Eine weitere Vereinfachung wieder, aber in der Linienführung eine Komplikation. Ich werde Ihnen morgen dann dieses Künstlerische, das darinnen liegt in dem Komplizierterwerden und in dem Einfacherwerden, durch eine einfache Darstellung auf der Tafel zeigen.

Hier sind wir nun schon angelangt an der Stelle, wo die Vorhangsspalte ist, wo also der große Kuppelraum in den kleinen übergeht. Sie haben hier die letzte Säule, den Anschluss zwischen dem großen und dem kleinen Kuppelraum.

Wir rücken nun noch weiter in den kleinen Kuppelraum vor. Sie sehen, es geht da in den kleinen Kuppelraum hinein.

Wir haben hier die Säulenfolge und Architrave des kleinen Kuppelraumes. Wenn Sie sich erinnern, wie die beiden Motive an den anderen Säulen waren, so werden Sie sehen, dass entsprechend der Tatsache, dass hier der Raum ein kleinerer ist, dass nur sechs Säulen sind, die Formen verändert sind. Sie brauchen sich ja nur folgende Gedanken zu machen: Hat man sieben Säulen, die eine geschlossene Entwicklung geben sollen, dann hat man jeder Säule eine andere Form zu geben. Dann denken Sie sich einmal, man hätte den gleichen Raum mit sechs Säulen statt mit sieben Säulen zu umkreisen, dann würde man Abstände haben zwischen den Säulen, die ein und ein Siebentel sind, also 8/7 sind im Verhältnis zu dem Früheren, dadurch aber jetzt einzelne Formen geändert. Und hier hat man außerdem den kleineren Kuppelraum. Dadurch wurden die Formen um ein Weiteres verändert. Sehen Sie, gerade wenn so etwas geschaffen wird, dann bekommt man dasjenige, was ich nennen möchte: Raumgefühl.

Wer abstrakt denkt - es sind ja solche Gedanken sogar in der wissenschaftlichen Literatur aufgetaucht -, der ist der Meinung, dass man zum Beispiel auch einen Menschen ganz klein, atomistisch klein vorstellen kann, dass die Größe selbst, der Rauminhalt keine Beziehung haben zu dem Wesen. Das ist aber nicht wahr. Wer sich in das Wesen des künstlerischen Schaffens versenkt, der weiß, dass eine bestimmte Form nur in einem bestimmten Rauminhalte wiedergegeben werden kann, dass die Größe des Raumes in einem inneren Verhältnisse zu dem steht, was dargestellt wird. Wenn man irgendeine Gestalt für einen bestimmt großen Raum gedacht hat, und man macht es dann en miniature, so erscheint sie einem quälend. Aber diese Empfindung muss da sein. So weit müssen die künstlerischen Dinge auf ihren Rauminhalt abgestimmt sein, sonst sind sie nicht wirklich künstlerisch gestaltet.

Das nächste Bild; wiederum eine andere Säulenfolge der kleineren Kuppel mit dem entsprechenden Architrav. Sie sehen hier wieder den Spalt für den Vorhang, die erste Säule, die zweite Säule und so weiter. Wir werden dann die einzelnen Säulen in ihrer Aufeinanderfolge noch studieren.

Die erste Säule der kleinen Kuppel.

Die nächste wird jetzt nach dem Wachstumsprinzip sich komplizierter darstellen.

Die nächste wiederum komplizierter.

Nun geht es nach der Vereinfachung hin, die aber eine Scheinvereinfachung ist; es ist eben ein Herauswachsen.

Die nächste Säule.

Da kommen wir schon an die zwei Säulen, die das Ostende eingrenzen.

Wir haben hier die Schnitzereien des Ostendes. Sie werden sie sehen, wenn Sie genau hinsehen. Ich möchte sagen, die Formen können hier mehr empfunden als gesehen werden. Wenn Sie genau zusehen, so werden Sie finden, dass in der Schnitzerei hier im Ostende all dasjenige zusammengefasst ist, was die anderen Formen der Säulen und der Architrave enthalten, natürlich aber für die Wölbung des Raumes geändert, metamorphosisch. Darüber ein Fünfblatt. Da kann sich ja jeder, der das will, das Pentagramm hineindenken, aber so, wie man es sich auch in ein fünfblättriges Pflanzenblatt der Natur hineindenken kann. Ein Symboliker würde dort irgendein Pentagramm angebracht haben. Aber dann würde man nach dem Prinzip handeln, nach dem vielfach bei uns gehandelt worden ist. Man hat es immer wieder erleben müssen, dass Künstler in unsere Zweigzimmer hineingekommen sind, die unangenehm berührt waren davon, dass sich überall unkünstlerische Motive gefunden haben. Ein Kreuz, das unschön gestaltet war, mit sieben Rosen ringsherum, das war etwas, was man als würdiger befunden hat als etwas wirklich in den künstlerischen Formen Lebendes.

Gerade wenn man in der Lage ist, das Geistige ganz auszugießen in die künstlerischen Formen, dann ist dasjenige erreicht, was hier erreicht werden soll: nicht aufdringliche Symbole, sondern ein Gestalten in den Formen, aber ein solches Gestalten in den Formen, in dem der Geist lebt. Wenn wir beschreiben, wie sich aus Saturn, aus Sonne, aus Mond die Erde entwickelt hat [Lücke im Text] dass in dem Ganzen darinnen das lebt, was auch in den Ideen unserer Weltanschauung lebt, dass es aber nicht lebt, indem es sich symbolisch durch irgendwelche Formen zum Ausdrucke bringt, sondern dass die Formen wirklich innerliche Wachstumskräfte in sich haben.

Sie sehen hier dieses Ostende etwas deutlicher in seinen einzelnen Formen.

Das nächste Bild; ein Detail von der Seite des kleinen Kuppelraumes.

Nun, meine lieben Freunde, damit habe ich begonnen, Ihnen anhand dieser Bilder etwas über den Bau auseinanderzusetzen. Ich werde morgen fortfahren mit dieser Auseinandersetzung, sodass auch diejenigen, die diese Auseinandersetzung zum ersten Mal hören, durch diese Darstellung ein geschlossenes Bild bekommen von dem, was unser Bau sein soll. Ich werde also morgen diese Betrachtungen anhand weiterer Lichtbilder hier fortsetzen.