| 205. Humanity, World Soul and World Spirit I: Tenth Lecture

10 Jul 1921, Dornach Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| 205. Humanity, World Soul and World Spirit I: Tenth Lecture

10 Jul 1921, Dornach Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

Yesterday, in closing, I called attention to the fact that, since that time, according to the spiritual-scientific point of view, we have to reckon the evolution of mankind on earth as having made a circuit from Pisces to Pisces. When I have spoken in this connection of the evolution of mankind on earth, it must naturally be correctly understood. We speak of the overall evolution of mankind in such a way that we let it begin in the old Saturn time, and therefore it can naturally only be a partial evolution of mankind when we speak here of the evolution of mankind on earth. But one can imagine it this way: During the time of Saturn, the Sun and the Moon, man quite naturally took on a very different form, one that cannot be compared to the present form of man. And when we speak here of the formation of humanity on earth, it means that the preparations for this physical human formation began at the end of the Lemurian age, that it developed in the way I have described in my writings, in the Atlantean time, thus precisely in the time that represents such a full cycle of the spring equinox of the sun. Now let us discuss the conditions to which man was subject during this time, when he had, so to speak, returned to his starting point. I would like to present something schematically so that you have the complete picture of what I actually mean with these explanations. We cannot say that human evolution has taken place in such a way since the last Lemurian period, when the spring point of the sun was also in Pisces, that we can depict this evolution as a cycle that simply returns to itself. That would be wrong. We have to think of this cycle, because of course I am only giving a picture of the development, we have to think of it as a spiral. We must therefore imagine that, if the starting point of evolution lies in the ancient Lemurian period here, this evolution returns in such a way that man has naturally risen to a higher level of his being, but at this higher level, in relation to his relationship to the cosmos, has in a sense returned to his starting point in the present age. And how he had to live in these circumstances, let us bring that to mind today.  Some time ago, I gave a lecture to a small group in Stuttgart about a possible astronomical world view. I pointed out how, for a long time, the so-called Ptolemaic world view was regarded as correct by mankind. This Ptolemaic conception of the world is thoroughly ingenious, it is so, I might say, in certain line forms geometrically summarizes that which must be summarized if we want to express the view we have of the stars, their positions and their orbits, by pictorial representations. Then, for certain reasons, which I have often described, this Ptolemaic system was replaced by the Copernican system, which, with some important modifications, is still regarded today as essentially correct. In Stuttgart, I showed that this Copernican system is nothing more than a linear representation of what we see when we look into the cosmos with our eyes, telescopes or other instruments. I also showed that it cannot be said that this Copernican system is any more correct than the Ptolemaic system; it is only a different way of summarizing the phenomena. And I have then tried to summarize these phenomena myself, linking them to what man – who, after all, if, for example, the earth has a movement, must go along with this movement – can experience within himself. Today I want to present only the result to you; the other is not important for us today. If we begin to summarize these phenomena not in a one-sided way, as is the case with both the Ptolemaic and Copernican world systems, but if we take into account everything that is available to us, then we come to the conclusion that this summary will ultimately become so complicated that we can no longer get by with a simple world system, which we can represent with a pencil or a planiglobe. It is not at all possible, basically, to summarize things in as simple a way as one would usually like to summarize them. And one can indeed arrive at something very strange in this way, which I would like to present to you quite simply, because, however paradoxical they may appear to people of the present day, these things must be discussed. People believe that the science of the present is the most intelligent thing that has ever existed, and that basically nothing more intelligent could possibly be invented. And because of this belief, humanity is indeed heading for a terrible cultural fate. But the right thing must also be presented in a certain way. If you take into account more and more circumstances, you will end up in such a state of mind regarding the complexity of the world system that this state of mind is very similar to the one you have when you have just woken up and experience the chaotic images of the soul, which I said yesterday and the day before yesterday sit in us as an undercurrent. I have schematically drawn the human organism for you according to etheric body and physical body and said: These chaotic images emerge from it, which are actually always there even during the day. They can be found very effectively in dreamy natures, but everyone notices them at the bottom of their soul. And they can be particularly strongly noticed when a person submerges with his ego and astral body into his physical and etheric bodies in the morning. Now I do not mean these images themselves – these images are, of course, very poetic and imaginative for the people concerned, depending on their level of perfection or imperfection, or they are very chaotic, the latter being the more common case. But I am talking about the state of mind that a reasonably logical person experiences when they are accustomed to thinking logically and then find themselves immersed in this world of images. What is meant is the state of mind that comes to those who do not approach it with all the prejudices and simplifications that prevail when constructing world systems, but who approach it without prejudice. Then, in relation to what one ultimately achieves, in relation to the complexity, in relation to the interweaving, one enters into a similar state of mind. Of course, our time has brought it about – and that is even a great boon compared to the mental disposition of most people – that every schoolboy knows exactly: at the focus of an ellipse is the sun, the planets revolve around it, the fixed stars stand still, and so on. – Every schoolboy knows this, and it is tremendously simple. But if you approach these things without prejudice and without theoretical fuss, you do not find this simplicity. Instead, things become enormously complicated, and in the end you arrive at the kind of frame of mind I have described, in which you say to yourself: you have to move into something that transitions from the definite to the indefinite, from the definitely drawn lines into problematically drawn lines. You enter into a frame of mind that tells you: What you are taking into your head is basically an image, an image that is woven and that you can simplify, as when you, say, make a diagram of Raphael's Madonna. But just as you would not have the whole of Raphael's Madonna from that, you have just as little in the Copernican system what is actually in front of us in space in the form of an image that includes an infinity of details and particulars. Just when you are considering such a consideration, you will understand: If we have to say something like that to ourselves when we contemplate the phenomena of the universe, then we cannot actually stand face to face with reality as such; for we stand before what presents itself to us in a state of soul like the world of images that we encounter when we enter our body from the cosmos in the morning. So there can be no question of standing face to face with reality. These are the kinds of considerations that must be made if one wants to have an understanding in the full sense of the word of what it actually means: we live with our consciousness in the world of illusion, of maya. We also live in Maya with regard to the image we have of the universe and its phenomena. And finally, we can also observe the phenomena that the sensory world weaves around us, and we come to something similar. We do not, however, come to what a, I would say, clumsy theory of knowledge has come to at the end of the 18th and in the course of the 19th century, which always repeats: Yes, out there the phenomena are, for example, through mechanical and dynamic laws, or as one says recently, electrons, and they exert an impression on our senses, and that which is then perceived by us, that is only an effect of that which is out there; but that is just only the appearance for us. To speak of appearances to us in this sense is, after all, a clumsy theory of knowledge. With such a view, one can indeed have some strange experiences. One need only turn against this theory of knowledge with a few lines here or there today, and someone will come along and say, “But Kant said...” People have become so wrapped up in Kantianism that they consider it a kind of Bible; at least many do. They change this or that, but on the whole they consider it a kind of Bible. One can have the strangest experiences there. I once held courses on such questions in Berlin, it was in the winter of 1900 to 1901, the same winter about which Herr von Gleich has proclaimed that a certain Winter taught me about Theosophy – he has confused the winter of 1900 to 1901 with a Mr. Winter who is supposed to have taught me about Theosophy! I don't know whether he read it or was told that I once gave these lectures in winter, which were then printed, they were given in Berlin in the winter of 1900 to 1901, and so the word “winter” was taken for the name of Mr. Winter. Yes, this argument is no more intelligent than the other stupid and dishonest arguments of General von Gleich. But you see, at these lectures in Berlin there was also a dyed-in-the-wool Kantian. I can't say he was listening, because he was usually asleep, and I don't know how many people can listen while sleeping, but I could tell at the time that he only woke up when he could somehow apply Kant. And once it happened that I repeated an argument – it wasn't even mine – in which it was said: If one really speaks of the thing in itself as being completely unknown, as Kant did, then it could consist of pins, so that behind the sensory phenomena there could only be pins. But when I said this, the person in question jumped up as if stung by an adder and said: Behind the phenomena is not space and time. There are pins in space, so the thing in itself cannot consist of pins! — It is just one of the examples that one so often encounters when people believe that their Bible, their Kantian Bible, is somehow being touched. Now, it is not the case that any “things in themselves” throw effects into us, so to speak, which then merely trigger sensory qualities, so that we are actually only wrapped up in our sensory qualities; it is not like that. But something else is true. Please just take the following: Stand outside at, say, 11 o'clock in the morning and look at the surrounding area, but look at it carefully, not as some people draw it, because what they draw is nonsense, of course it doesn't reflect the appearance of the senses. Instead, look at it at 11 o'clock, at 12 o'clock with all its lighting effects. The whole sensory tapestry has changed completely by noon, by five o'clock, by eight o'clock. The picture around you is constantly changing. You are never dealing with anything but interwoven effects and impressions. A tree – what do you see of the tree? You see the reflected light, you may see the leaves moving in the wind, and so on. In short, you never see anything permanent. You simply see an objective appearance. While the clumsy theory of knowledge speaks of a subjective appearance, you see an objective appearance, and this objective appearance naturally also communicates itself to the eye. Just as the tree intercepts the light rays in a certain way, reflects them and so on, so the eye also has a certain relationship to the light rays, and we can say: the phenomenal, the apparent, the illusory , the Maja nature, which is spread out in the sense world around us, is of course also present in our subjective picture; but because it is objectively changeable, it is also changeable in the subjective picture. This is what I wanted to substantiate, for example, in the first section of my “Philosophy of Freedom” or in my booklet “Truth and Science” and so on. So even when we face the world, we are not dealing with a lasting, permanent reality; we are dealing with something that, one might say, is coming and going in the moment. We are dealing with appearances. And if we wanted to construct this image theoretically, we would come up with nothing more than the few lines in the Sistine Madonna. And so it is in everything we are immersed in. We are immersed in the world of phenomena, of Maja, but even though we are immersed in this world of Maja with all our perception, we are not dependent on this world. For it is quite clear to us when we emerge from the cosmos with our I and our astral body in the morning and submerge into our etheric body and our physical body, that what we are submerging into contains an objective, a truth. Certainly, what swirls towards us as chaotic images is only an appearance; but what we submerge ourselves in contains a truth. And in the moment when we submerge ourselves, whether we do so through: I want to move my limbs, or through: I want to bring my ideas into fantasy forms, or let's say through: I want to bring my ideas into logical thought connections – in what becomes us when we immerse ourselves in our body, in that, we know, we have something that does not depend on us, that we receive, that receives us. And the moment we wake up is the one that communicates our sense of being to us. This sense of being is, in a sense, something that permeates and runs through our entire thinking. But our thinking itself moves more in the world of phenomena, of appearance, of maya. And let us expand what I am presenting from ordinary experiences to include the whole person. Those who, with the help of such insights, as can be gained on the basis of my descriptions in “How to Know Higher Worlds”, can look at the whole person, will soon know how the human being, as a soul-spiritual being, goes through the state between death and a new birth, how it penetrates into the physical world, becomes embodied, in order to go through the state between birth and death, and then again a state between death and a new birth. I have developed some important details about these processes in the last lectures here. When the moment comes when one can look back into the world that lies before birth or before conception, one realizes that we have gone through the world that actually makes up our sense of being, the world from which our sense of being comes, between death and a new birth. One only acquires the right feeling for being, the feeling for being that is not subject to doubting or skepticism, when one looks back into this world of existence that lies before conception. But now something significant appears, as you can already gather from my Viennese lectures from the spring of 1914. I will now present it to the soul in a different form, namely, something appears that confronts us before the human being descends from the state between death and a new birth to his physical embodiment. During this time, the desire to be, the desire to exist, fades more and more from the human being. As he develops between death and a new birth, I would say that the human being passes through an absolute satiation with the feeling of being. That is one of the achievements that man acquires between death and a new birth, that after going through the first stages after death, he comes more and more, through the relationship to the world into which he then enters, to a strongly penetrating feeling of being, to a — if I may use the expression — being anchored in the being of the world. And this becomes stronger and stronger until a kind of supersaturation with the feeling of being occurs, and then, towards the end of the time between death and a new birth, I would say that a true supersaturation with the feeling of being occurs. I could also call it something else. I could say that a true hunger for non-being occurs in the human being. Those spiritual-soul entities that come down to earth as human beings actually show, before they come down to earth, a strong hunger for non-being. And from this state of mind or spirit, we could say: Because man hungers for non-being, he plunges into Maja in this state, into the world that we have before us both in relation to the world of stars and in relation to the earthly phenomenal world. There is a longing for this non-existent world, for this world, which one is in soul moods towards, as one is towards the chaotic images when one goes to their bottom, this world, which actually presents us with a different aspect in every moment. We are, after all, completely immersed in an illusory world, in a Maya world, as we immerse ourselves in this world. The soul and spirit want to submerge themselves in this Maya world, and that is what we are actually dealing with. The others are more or less side effects. This is the strongest impulse that lives in the spiritual-soul human being when he approaches earthly existence: this longing for Maya, this longing to live in the soft, permeable phenomenon, not in the saturated, intense being. And what then envelops the human being as an etheric body and as a physical body has been born out of the cosmos and is used to clothe the human being. In the last few days, I have described how the embryo in the mother's body is formed out of the cosmos. We must therefore imagine that the human being basically comes from a completely different world. There he acquires this hunger for existence, for life in the Maja, by approaching the physical earthly existence, and he is received by plunging into the Maja with his I and with his astral (see drawing, red, blue), of which the etheric body and the physical body (yellow, red) are formed in the maternal body through fertilization as its covering from the cosmos. The human being comes from a world that is not spatial-temporal, that cannot be found in space, but he is clothed in space with what is formed in the mother's body. He then emerges into this every time he wakes up. When falling asleep, he emerges from it. A rhythm of submerging into the physicality and of being drawn out of it is formed.  Today's ideas are actually such that one has great difficulty in dealing with them in relation to reality. This convergence, for example, of a completely different current that a person goes through before he comes to his embodiment, and the external that then envelops him, which of course has nothing essential to do with him before - as it really becomes, I have described on other occasions - this interaction, that can hardly be described by today's science in an appropriate way because it lacks the concepts for it. The same thing can be seen in another area. When a physiologist talks about light or color today, his main concern is to describe something that the eye does, to find out what it is. But in reality it is actually just as if someone wanted to describe any of the personalities sitting here and, above all, describe this carpentry workshop here because you walked in here. Basically, the light that enters the eye and takes effect in the eye has no more to do with the eye than you have with the carpentry workshop when you walked in and the carpentry workshop now also envelops you. If someone describes the carpentry workshop and you, they naturally describe it as a whole. But that is not the case. It is difficult to find the truth in the face of today's complicated ideas. And so we can say: that which is spiritual and soul in man comes into this world of the earthly primarily out of an urge for non-being. And every waking state, that is, every state that is experienced from waking up to falling asleep, is a new education for being, a re-impregnation of consciousness with being. The human being is in the state in which he is last between death and a new birth, I would like to say, so glad when he can arrive at his physical embodiment, he is so glad. I have often described to you how the brain floats in the cerebral fluid. If the whole weight, one thousand three hundred and fifty grams or something like that, were to press on the veins under the brain, the veins would be crushed, they could not exist; but the brain only presses with about twenty grams. Why? Because the brain floats in the cerebral fluid. And you know Archimedes' principle. Right, it was Archimedes who found it. He was once in a tub bathing and felt how he was getting lighter and lighter in the bath, and he was so pleased about this discovery that he immediately ran naked through the streets shouting: I've got it, I've got it!” — namely, that every body in a liquid loses as much of its weight as the weight of the water body that it displaces. So if you have a container of water and you put a solid object in it, it becomes lighter than it actually is outside the water, and it becomes lighter by the amount that the displaced water weighs, that is, by its own weight, if you think of it as being made out of water. So if, for example, there were a cube here and you thought of it as a water cube and weighed it, the actual cube would become lighter by the weight of the water cube. And so the brain becomes lighter, except for twenty grams, weighs only twenty grams because it floats in brain water. So the brain does not follow its full gravity. It is pushed upwards. This force that pushes upwards is also called buoyancy. Man looks forward to this, to coming into something that actually pulls him upwards, that really pulls him upwards. And he learns to be heavy again at twenty grams, and through heaviness we learn the feeling of being. Man is again imbued with the feeling of being between birth and death. And this is then developed and increased in the evolution after death. This is what, I would say, has so disappeared from the consciousness of modern humanity that the greatest philosopher at the beginning of this newer time, Cartesius or Descartes, coined the formula: Cogito ergo sum - I think, therefore I am. - It is the most nonsensical formula one can think of, because precisely by thinking, one is not. One is precisely outside of being. Cogito ergo non sum – is the real truth. Today we are so far removed from the real truth that the greatest modern philosopher has put the opposite in the place of truth. We acquire the feeling of being precisely when thinking feels itself in the organism, when thinking feels itself embedded in what is heavy. This is not just a popular image, it is reality in the face of appearances. But this can teach us how the human being, as he initially knows himself, goes down to earth in knowledge, actually submerges himself in the Maja and, within the Maja, learns what he needs again after death: the feeling of being. Now, when one describes what I have described to you now, then one has something that is specifically human in human development. This, I would like to say, rhythmic movement between the feeling of being and the feeling of not being can be visualized for meditation in the following way. You can say, when you live in mere thoughts: I am not. When one lives with reference to the will, which physically rests in the metabolic-limb-human being, then one says: I am. And between the two, between the metabolic-human being and the pure brain-human being, who says: I am not, when he understands himself, because that which lives in the brain are merely images; that which lies in between is the rhythmic alternation between: I am and I am not. For this, the external physical is breathing. The exhalation fulfills the breathing process with what comes from the metabolism, with carbon dioxide. I am – is exhalation. I am not – is inhalation. I am not

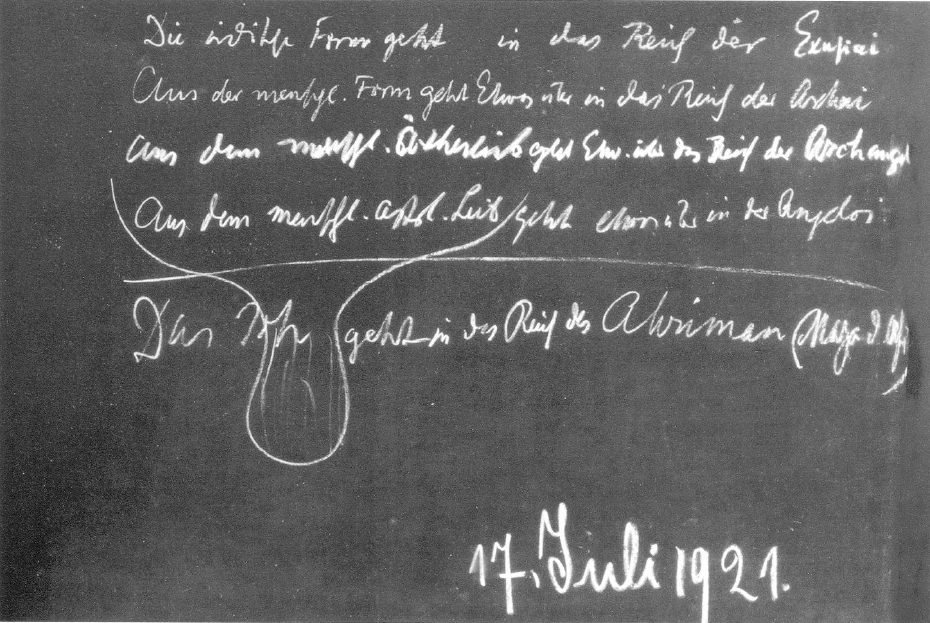

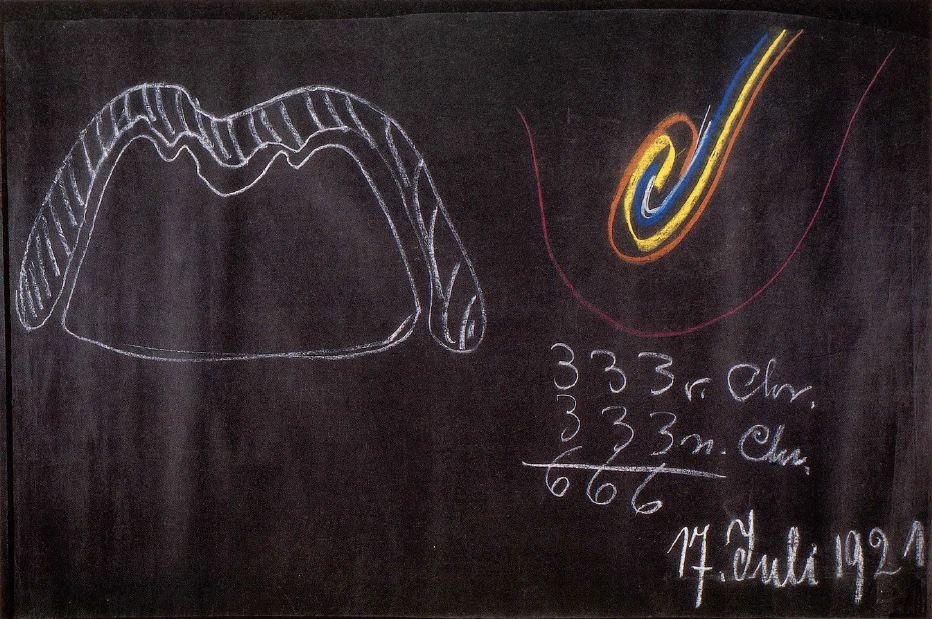

The inhalation is related to: I am not - of thought. Inhalation happens in such a way that we take in air into our ribs, pushing the water of the arachnoid space upwards and thereby pushing the cerebral fluid upwards. We bring the vibration of the breathing process into the brain. This is the organ of thought. The inhalation process transmitted to the brain: I am not. Again, exhalation, the cerebral fluid – through the arachnoid space – presses on the diaphragm, exhalation, the air impregnated with carbon, turned into carbonic acid: I am – out of the will. Exhalation: out of the will. All this, understood in this way, is a purely human process, because the person who wants to transfer it to the animal, because the animal also breathes, is just like a human being who takes a razor to cut his flesh because it is a knife. Of course animals also breathe, but animal breathing is something different from human breathing, just as a razor is something different from a table knife. Those who base their definitions on the outward appearance of things will never arrive at any kind of useful explanation of the world. Death is something different for humans, something different for animals, something different for plants. Anyone who starts from a definition of death will come to just as little of a useful explanation as someone who starts from the definition of a knife and says, for example, “A knife is something that is so fine on one side that it cuts through other objects.” Of course, that gives a nice general concept, but one cannot understand anything about what really is. So, these are specifically human processes that I have described to you. They are the human processes that man has gone through while the vernal point made the circuit from Pisces to Pisces. This is precisely the time in the evolution of the earth when man, in the leading parts of the nations, has gone through everything that I have described to you now, and which all tends to show how it actually happens, how man, human being, by descending into the physical world through birth, plunges into the maja, and with death is reborn out of the maja again, enriched by the feeling of being, which he needs for the further life after death. This is the most important fact: this being born through death with the feeling of being, while being born is the human being's spiritual-soul entity plunging into maya. It is precisely because we plunge into maya, that is, into a world of images, that we are free. We could never be free if we were in a world of facts with our consciousness between birth and death. We are only free because we are in a world of images. Images that are in the mirror do not determine us causally. A world of facts would determine us causally. What you bring to the image that hangs before you must come from you. The phenomena of the world do not determine us as human beings in what I called in my Philosophy of Freedom pure thinking, which does not come from the organism. What comes from the organism is, as you have seen, imbued with the sense of being, even if in the brain this sense of being is present in such a small percentage that it is about twenty to one thousand three hundred and fifty. One must look at this again and again, how man actually develops the longing for Maja by being born into earthly life, and how earthly life educates him to the feeling of being. That is what we have gone through during the time from the last Lemurian period into our period, where a sun cycle of 25,920 years, a great world cycle, has been gone through. Now, however, we are in the time in which development has returned to its starting point, but I have drawn it in such a way that I said: we have to indicate it schematically in a spiral (see drawing on page 170). The development of humanity has indeed returned to its starting point, but at a higher level. But what does this higher level mean? This higher stage means that we, as humanity, have always plunged into Maya with our birth and then, out of our physical existence, have gained the feeling of being. But the earth has also changed in the meantime; the earth today is no longer the same organism that it was in the Lemurian or Atlantean times. Today, as I have often stated, the Earth is already in a process of dissolution. Geology also knows this. Read about it in the beautiful geological works of Eduard Sueß, 'The Face of the Earth': the Earth is in a crumbling process, the Earth is in a dissolution process. This means that we will no longer have every opportunity to acquire the feeling of being in a sufficient way. And now that a cycle has been completed, as I explained yesterday and today, humanity is facing the danger of going through deaths in which it has developed too little sense of being, simply because our earth no longer provides the necessary intensity of the feeling of being. With this new period, which I have now explained to you as a period of the whole cosmos, the prospect opens up for humanity to pass through death with a feeling of lightness that is, if I may express it so, too great. Humanity may become more and more materialistic, and the consequence of this, if it becomes more and more materialistic, will be that it carries an insufficient feeling of heaviness or being through the gate of death. This is something that is already quite clear to those who are familiar with the conditions in the world today: souls today are carried through the gate of death by their own sense of non-being, so that they experience the opposite of what a person who falls into water and cannot swim experiences — they sink. These souls sink when they pass through the gate of death, due to the little weight they have. How the expression 'weight' is used in the spiritual world, that occurs at an important point in my Mysteries. They rise to the top and are lost. This can only be counteracted by people rising from concepts that can be easily acquired today and that figure in our entire lives, to that which must be achieved with a certain effort of physical life: that is, such concepts that are not produced by physical life alone, that are acquired through spiritual science. What do people who absolutely want to remain in today's thinking say about spiritual science? They say: Yes, what is described, for example, in this Steinerian “occult science”, that is fantastic, that is arbitrary, that cannot be imagined! Why do people say that? People can see chalk, they can see tables, they can see legs, and they can only imagine what has once presented itself to them in this way; they do not want to imagine anything other than what they have appropriated from the bellwether of external physical reality. They do not want to develop any inner activity in imagining. Anyone who wants to study Occult Science: An Outline must make an effort themselves. If he gapes at an ox, he has a reality, to be sure; he needs not make any effort, but only gape at it and then form a so-called concept, which is no concept at all. What it is about is that the concepts that are hinted at by spiritual science, for example by my “Occult Science” or “Theosophy” or by the other books, demand this inner activity. A large part of humanity, which is now more materialistic than ever because it wants to educate the world of ideas in a materialistic way, the spiritualists, would really rather not get involved in thinking through and working through Occult Science; they prefer to let themselves be by Schrenck-Notzing or others, where such lumps, shaped like human beings or the like, appear to them in such a way that they can remain completely passive; they do not need to make any effort at all. But in doing so, one becomes lighter and lighter and works against one's continued existence after death. However, by working one's way into the activity needed to penetrate spiritual science, one has to make a greater physical effort, connect more strongly with the physical than is the case today under so-called normal conditions. One must use stronger concepts. But in so doing, one also takes one's sense of being with one through death and is then equal to life after death. That is something, is it not, that today's man likes so much: to add nothing to what he encounters in life. If he is to add something, to be active, it immediately becomes uncomfortable for him. Outwardly, in our social lives, we have always striven to learn as much as possible and to learn according to the templates prescribed by the state; so that when we have happily reached the age of twenty-five or twenty-six and are ready to start our legal clerkships, we are then pushed into some scheme and entitled to a pension after so many decades; now we are safe. We are only in our twenties, but we are insured for life. We let our body retire – that is guaranteed from the outset – then comes the church, the church confession, which also demands nothing more than that we passively surrender to what is offered to us. And the church then retires our soul when we are dead; it insures us against it without our doing anything, except at most living in faith, just as our body was retired before. This is something that must be broken with if civilization is not to arrive at its decline. Inner activity, inner active participation in what man makes of himself, even what he makes of himself as an immortal being, is necessary. Man must work on his immortality. That is the one thing that most people would like to be magically removed. They believe that knowledge can only teach one something of what is so anyway, can at most teach one that man is immortal. There are those who say: Yes, I live here, as life exists here; what will be after death, I will see then. He will see nothing, absolutely nothing! For the argument is about as ingenious as that of the Anzengruber personality: “As surely as there is a God in heaven, I am an atheist!” — These things are of the same logic. The fact of the matter is that, with regard to the spiritual and mental, by taking it into our knowledge, we make the spirit mature so that after death it does not go through the opposite state of someone sinking in confusion, that is, of someone rising without essence. We must work on our essence so that it can pass through death in the right way. And the assimilation of spiritual knowledge is not just the assimilation of abstract knowledge, it is the penetration of the spiritual and mental life of man with the forces that conquer death. This is, after all, the essence of the Christian teaching. Therefore, a person should not merely believe in Christ, as a modern confession would have it, but should take to heart the words of St. Paul: “Not I, but Christ in me.” The power of Christ in me must develop and be cultivated! Faith as such cannot save the human being, but only the inner cooperation with Christ, the inner development of the power of Christ, which is always there if one wants to develop it, but which must be developed. Initiative and activity are what humanity will have to fill itself with. And it must realize that mere passive faith makes man too easy, so that in time immortality would die on earth. That is Ahriman's endeavor. And to what extent it is Ahriman's endeavor, we will then bring before our soul in a next lecture, because today we are in the midst of the battle between the Ahrimanic and the Luciferic powers. And just as we have protected our unconsciousness to a certain extent, with the spring equinox marking a boundary, we will have to enter the next boundary in such a way that we place ourselves with full 1987 we place ourselves in that which interweaves the world's being: the battle of the Luciferic with the Ahrimanic spirits. Through spiritual science we are led into reality, not just into an abstract knowledge. More about this next time. |

| 205. Humanity, World Soul and World Spirit I: Eleventh Lecture

15 Jul 1921, Dornach Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| 205. Humanity, World Soul and World Spirit I: Eleventh Lecture

15 Jul 1921, Dornach Rudolf Steiner |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

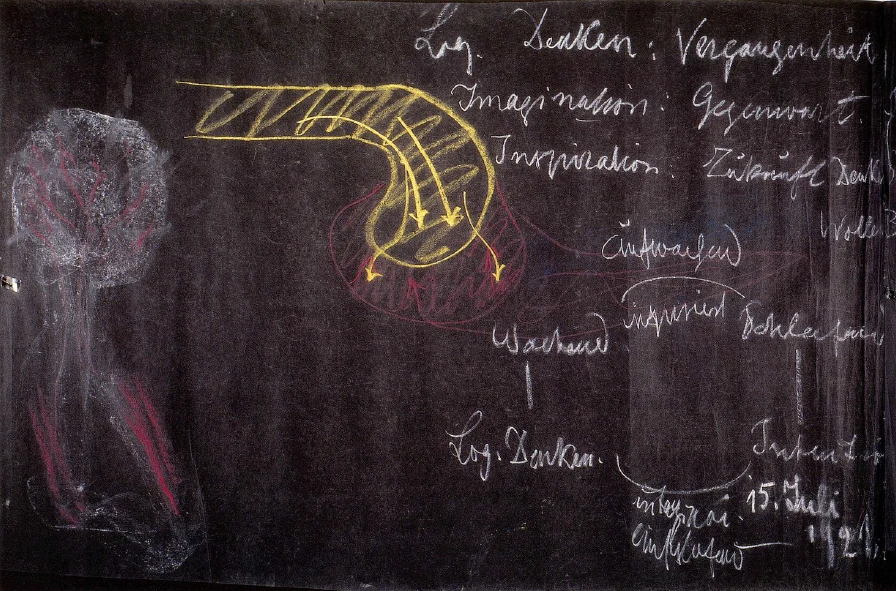

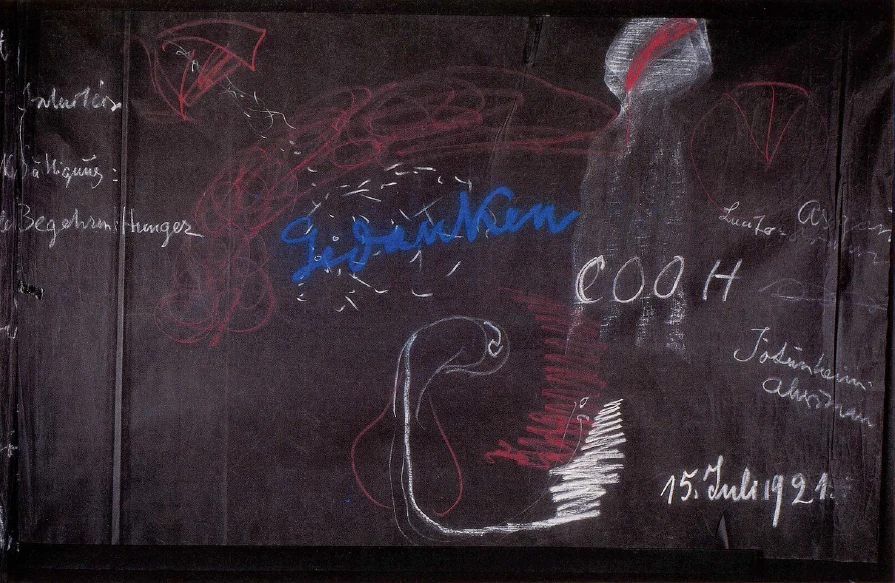

Today I will summarize some truths that will serve us in turn to provide further explanations in a certain direction in the coming days. If we consider our soul life, we can say that towards one pole of this soul life lies the element of thinking, towards the other pole the element of will, and between the two the element of feeling, that which in ordinary life we call feeling, the content of the mind, and so on. In the actual life of the soul, as it takes place in us in our waking state, there is never just one-sided thinking or will, but they are always in connection with each other, they play into each other. Let us assume that we behave very calmly in life, so that we can say, for example, that our will is not active externally. However, when we think during such outwardly directed calmness, we must be aware that will is at work in the thoughts we unfold: in connecting one thought with another, will is at work in this thinking. So even when we are seemingly merely contemplative, merely thinking, at least inwardly the will is present in us, and unless we are raving or sleepwalking, we cannot be willfully active without letting our volitional impulses flow through thoughts. Thoughts always permeate our volition, so that we can say: the will is never present in the life of the soul in isolation. But what is not present in this isolated way can still have different origins. And so the one pole of our soul life, thinking, has a completely different origin than the life of the will. Even if we only consider everyday life, we will find that thinking always refers to something that is there, that has prerequisites. Thinking is mostly a reflection. Even when we think ahead, when we plan something that we then carry out through the will, such thinking is based on experience, which we then act upon. In a certain respect, this thinking is, of course, also a reflection. The will cannot be directed towards what is already there. In that case, it would always be too late. The will can only be directed towards what is to come, towards the future. In short, if you reflect a little on the inner life of thought, of thinking and of the will, you will find that even in ordinary life, thinking relates more to the past, while the will relates to the future. The inner life of feeling stands between the two. We accompany our thoughts with feeling. Thoughts please us, repel us. Out of our feeling we lead our impulses of will into life. Feeling, the content of the mind, stands between thinking and willing, right in the middle. But just as it is the case in ordinary life, even if only in a suggestive way, so it is in the great world. And there we have to say: what constitutes our thinking power, what makes up the fact that we can think, that the possibility of thought is in us, we owe it to the life before our birth, or rather before our conception. In the little child that comes to meet us, all the thinking abilities that a person develops are already present in the germ. The child uses thoughts only - as you know from lectures I have already given - as directing forces to build up its body. Especially in the first seven years of life, until the change of teeth, the child uses the powers of thought to build up its body as directing forces. Then they emerge more and more as actual thought forces. But they are thoroughly predisposed in the human being as thought forces when he enters physical, earthly life. What develops as will forces - an unbiased observation readily reveals this - is actually connected with this thought force only to a small extent in the child. Just observe a wriggling, moving child in the first weeks of life, and you will already realize that this wriggling, this chaotic movement, has only been acquired by the child because his soul and spirit have been clothed with physical corporeality by the physical external world. In this physical body, which we only develop little by little from conception and birth, the will initially lies, and the development of a child's life consists in the fact that gradually the will is, so to speak, captured by the powers of thought that we already bring with us into physical existence through birth. Just observe how the child at first moves its limbs quite senselessly, as it comes out of the activity of the physical body, and how gradually, I might say, thought intrudes into these movements, so that they become meaningful. So there is a pressing and thrusting of thinking into the life of the will, which lives entirely within the shell that surrounds the human being when he is born, or rather, conceived. This life of the will is contained entirely within it.  So that we can draw a schematic picture of a human being, in which we say that he brings his life of thought with him when he descends from the spiritual world. I will indicate this schematically (see drawing, yellow). And he begins his life of will in the physical body that is given to him by his parents (red). The forces of will are within, expressing themselves in a chaotic manner. And within are the powers of thought (arrows), which initially serve as directing forces to spiritualize the will in its corporeality in the right way. We then perceive these forces of will when we pass through death into the spiritual world. But there they are highly organized. We carry them through the gate of death into spiritual life. The powers of thought that we bring with us from the supersensible life into earthly life, we actually lose in the course of earthly life. With human beings who die young, it is somewhat different. For now, let us speak first of normal human beings. A normal human being who lives past the age of fifty has basically already lost the real powers of thought that were brought along from the previous life and has just retained the directional powers of the will, which are then carried over through death into the life that we enter when we go through the gate of death. One can assume that someone is now thinking: Yes, so if you are over fifty years old, you have lost your thinking! - In a sense, this is even the case for most people who are not interested in anything spiritual today. I would just like you to really endeavor to register how much original, inventive thought power is produced by those people today who have reached the age of fifty! As a rule, it is the thoughts of earlier years that have automatically moved on and left an impression on the body, and the body then moves on automatically. After all, the body is a reflection of our mental life, and the person continues in the old rut of thought according to the law of inertia. Today, the only way to protect oneself from continuing in the old rut of thought is to absorb thoughts during one's lifetime that are of a spiritual nature, that are similar to the thought-forces in which we were placed before our birth. So that indeed the time is approaching when old people will be mere automatons if they do not take care to absorb thought-forces from the supersensible world. Of course, man can continue to think automatically; it may appear as if he is thinking. But it is only an automatic movement of the organs in which thoughts have been laid, have been woven in, if the human being is not grasped by that youthful element that comes when we absorb thoughts from spiritual science. This absorption of thoughts from spiritual science is certainly not just any kind of theorizing, but it intervenes quite deeply in human life.  But the matter takes on particular significance when we now consider man's relationship to the surrounding nature. I now understand by nature all that surrounds us for our senses, to which we are thus exposed from waking up to falling asleep. This can be considered in a certain way in the following way. One can visualize what one sees — I mean before spiritual eyes. We call it the sensory carpet. I will draw it schematically. Behind everything that one sees, hears, perceives as warmth, the colors in nature and so on – I draw an eye as a schema for what is perceived there – there is something behind this sensory carpet. Physicists or people of the present world view say: Behind it are atoms and they swirl -, and afterwards, right, as they continue to swirl, there is no sensory carpet at all, but somehow in the eye or in the brain or somewhere or not somewhere, they then evoke the colors and the sounds and so on. Now, please, imagine, quite impartially, that you begin to think about this sensory carpet. If you start thinking and do not assume the illusion that you can observe this huge army of atoms, which the chemists have arranged in such a military way of thinking, let us say, for example, there is Corporal C, then two privates, C, O, O, and then another private as an H; isn't that right, that's how we arranged it militarily: aether, atoms and so on. Now, if, as I said, you do not succumb to this illusion but remain with reality, then you know: the sensory carpet is spread out, the sensory qualities are out there, and what I still grasp with consciousness about what lies in the sensory qualities is just thoughts. In reality, there is nothing behind this sensory carpet but thoughts (blue). I mean, behind what we have in the physical world, there is nothing but thoughts. We will talk about the fact that these are carried by beings. But you can only get behind what we have in our consciousness with thoughts. But the power to think we have from our prenatal life or from the life before our conception. Why is it then that we can penetrate behind the sensory curtain by means of this power? Just try to familiarize yourself with the idea that I have just mentioned, and try to properly present the question to yourself on the basis of what we have just hinted at, which we have already considered in many contexts. Why is it that we can reach below the sensory level with our thoughts, when our thoughts come from our prenatal life? Very simply, because behind it is that which is not in the present at all, but which is in the past, which belongs to the past. That which is under the carpet of sense is indeed a past, and we only see it correctly when we recognize it as a past. The past has an effect on our present, and out of the past sprouts that which appears to us in the present. Imagine a meadow full of flowers. You see the grass as a green blanket, you see the meadow's floral decoration. That is the present, but it grows out of the past. And if you think through this, then underneath it you do not have an atomistic present, but in reality you have the past as related to what comes from you yourself from the past. It is interesting: when we begin to reflect on things, it is not the present that is revealed to us, but the past. What is the present? The present has no logical structure at all. The sunbeam falls on some plant, it shines there; in the next moment, when the direction of the sunbeam is different, it shines in a different direction. The image changes every moment. The present is such that we cannot grasp it with mathematics, not with the mere structure of thought. What we can grasp with the mere structure of thought is the past, which continues in the present. This is something that can reveal itself to man as a great, as a significant truth: When you think, you basically only think the past; when you spin logic, you basically reflect on what has passed. - Anyone who grasps this thought will no longer seek miracles in the past either. For in that the past is woven into the present, it must be in the present as it is in the past. If you think about it, if you ate cherries yesterday, that is a past action; you cannot undo it because it is a past action. But if the cherries had the habit of making a mark somewhere before they disappeared into your mouth, that mark would remain. You could not change this sign. If every cherry had registered its past in your mouth after you had eaten cherries yesterday, and someone came and wanted to cross out five, he could cross them out, but the fact would not change. Nor can you perform any miracle with regard to all natural phenomena, because they are all intrusions from the past. And everything we can grasp with natural laws has already passed, is no longer present. You cannot grasp the present other than through images; that is a fluctuating thing. When a body lights up here, a shadow is created. You have to let the shadow properly define itself, so to speak, and so on. You can construct the shadow. That the shadow really comes into being can only be determined by devotion to the picture. So that one can say: even in ordinary life, limitation, I could also say logical thinking, refers to the past. And the imagination refers to the present. In relation to the present, man always has imaginations. Just think, if you wanted to live logically in the present! No, to live logically means to draw one concept from another, to move from one concept to another in a lawful manner. Now, just imagine yourself in life. You see some event: is the next one logically connected to it? Can you logically deduce the next event from the previous one? When you look at life, are not its images similar to a dream? The present is similar to a dream, and only that the past is mixed into the present, which causes the present to proceed in a lawful, logical manner. And if you want to divine something in the future in the present, yes, if you just want to think of something you want to do in the future, then that has happened in a completely non-representational way in the first instance. What you will experience tonight is not in your mind as an image, but as something more non-pictorial than an image. At most, it is in your mind as inspiration. Inspiration relates to the future. Logical thinking: past Imagination: present Intuition Inspiration: future.

We can also use a simple diagram to visualize what is involved. When a person – let me characterize him here by this eye (see drawing on page 198) – looks at the tapestry of the senses, he sees it in its transforming images, but he now comes and introduces laws into these images. He develops a natural science out of the changing images of the sensory world. He develops a specialized science. But think about how this natural science is developed. You investigate, you investigate while thinking. You cannot possibly, if you want to develop a science about what spreads out as a carpet of senses, a science that proceeds in logical thoughts, you cannot possibly gain these logical thoughts from the external world. If what is recognized as thoughts and laws of nature were to follow from the external world itself, then it would not be necessary for us to learn anything about the external world. Then the person who, for example, looks at this light would have to know the exact electrical laws and so on, like the other person who has learned it! Equally, if he has not learned it, man knows nothing at all, let us say, about the relationship of an arc to the radius and so on. We bring forth from our inner being the thoughts that we carry into the outer world. Yes, it is so: what we carry into the outer world as thoughts, we bring forth from our inner being. We are first of all this human being, who is constructed as a head human being. This human being looks at the carpet of senses. Inside the carpet of senses is what we reach through thoughts (see drawing page 198, white) and between this and between what we have inside us, what we do not perceive, there is a connection, so to speak an underground connection. Therefore, what we do not perceive in the external world because it extends into us, we bring out of our inner being in the form of thought life and place it in the external world. This is how it is with counting. The external world does not present anything to us; the laws of counting lie within our own inner being. But that this is true arises from the fact that between these predispositions, which are there in the external world, and our own earthly laws, there is an underground connection, a sub-physical connection, and so we draw the number out of our inner being. It then fits with what is outside. But the path is not through our eyes, not through our senses, but through our organism. And that which we develop as human beings, we develop as whole human beings. It is not true that we grasp some law of nature through the senses; we grasp it as a whole human being. These things must be considered if we want to properly bring to mind the relationship between man and the environment. We are constantly in imaginations, and one need only compare life with dreams without prejudice. When a dream unfolds, it is certainly very chaotic, but it is much more similar to life than logical thinking. Let us take an extreme case. If you take a conversation between reasonable people of the present day, you listen and you talk yourself. Think about what is said in the course of, say, half an hour, and whether there is more coherence in the succession of thoughts than there is in dreams, or whether there is as much coherence as in logical thinking. If you were to demand that logical thinking develops there, you would probably be greatly disappointed. The present world presents itself to us entirely in images, so that basically we are actually dreaming all the time. We have yet to bring logic into it. We wrest logic from our prenatal existence; we first bring it into the context of things and thereby also encounter the past in things. We embrace the present with imagination. When we observe this imaginative life that constantly surrounds us in the sensual present, we can say to ourselves: this imaginative life gives itself to us. We do nothing to it. Just think how hard you had to work to arrive at logical thinking! You didn't have to make any effort to enjoy life, to observe life; it reveals its images to you by itself. Now, that's how it is in life with imagining the images of the ordinary world around us. But all one needs is to acquire the ability to make images – but now through one's own activity, as one otherwise does in thinking – and to experience images through inner effort, as one otherwise does in thinking. Then one not only sees the present in images, but one also extends pictorial imagination to life before birth or before conception, and one sees before birth or before conception. And when you look into these images, then thinking is populated with the images, and then prenatal life becomes reality. We just have to be able to think in images by training the abilities that are spoken of in “How to Know Higher Worlds”, without these images coming to us by themselves, as is the case in ordinary life. When we make this life of images, in which we actually always live in ordinary life, into an inner life, then we look into the spiritual world, and then we do see the way in which our life actually unfolds. Today, it is considered almost exclusively spiritual when someone – I have spoken about this often – truly despises material life and says: I strive towards the spirit, matter remains far beneath me. This is a weakness, because only the one who does not need to leave matter below him, but who understands matter itself in its effectiveness as spirit, who can recognize everything material as spiritual and everything spiritual, even in its manifestation as material, only he truly attains a spiritual life. This becomes especially significant when we look at thinking and willing. At most, language, which contains a secret genius within it, still has something of what leads to knowledge in this field. Consider the basis of will in everyday life: you know that it arises from desire; even the most ideal will arises from desire. Now take the coarsest form of desire. What is the coarsest form of desire? Hunger. Therefore, everything that arises from desire is basically always related to hunger. From what I am trying to suggest to you today, you can see that thinking is the other pole, and will therefore behave like the opposite of desire. We can say: if we base desire on the will, we have to base thinking on satiation, on being full, not on hunger. This actually corresponds to the facts in the deepest sense. If you take our head organization as human beings and the other organization that is attached to it, it is indeed the case that we perceive. What does it mean to perceive? We perceive through our senses. As we perceive, something is actually constantly being removed within us. Something passes from the outside into our inner being. The ray of light that enters our eye actually carries something away. In a sense, a hole is drilled into our own matter (see drawing on page 201). There was matter, but now the beam of light has drilled a hole into it, and now there is hunger. This hunger must be satisfied, and it is satisfied from the organism, from the available food; that is, this hole is filled with the food that is inside us (red). Now we have thought, now we have thought what we have perceived: by thinking, we continually fill the holes that sensory perceptions create in us with satiety that arises from our organism. It is extremely interesting to observe, when we consider the organization of the head, how we fill the holes that arise in our remaining organism through the ears and eyes, through the sensations of warmth; there are holes everywhere. Man fills himself completely by thinking, by filling that which is there, in the holes (red). And it is similar with us if we want it to be. Only then it does not work from outside in, so that we are hollowed out, but it works from within. If we want, hollows arise everywhere in us; these must in turn be filled with matter. So that we can say, we receive negative effects, hollowing out effects, both from outside and from inside, and constantly push our matter into them. These are the most intimate effects, these hollowing effects, which actually destroy all earthly existence in us. Because by receiving the ray of light, by hearing the sound, we destroy our earthly existence. But we react to this, we in turn fill this with earthly existence. So we have a life between the destruction of earthly existence and the filling of earthly existence: luciferic, ahrimanic. The Luciferic is actually constantly striving to partially turn us into something non-material, to completely remove us from our earthly existence; for if he could, Lucifer would like to spiritualize us completely, that is, dematerialize us. But Ahriman is his opponent; he works in such a way that what Lucifer excavates is constantly being filled in again. Ahriman is the constant filler. If you form Lucifer plastically and make Ahriman plastically, you could quite well, if the matter went through in confusion, always push Ahriman into the cavity of Lucifer, or put Lucifer over it. But since there are also cavities inside, you also have to push in. Ahriman and Lucifer are the two opposing forces at work in man. He himself is the state of equilibrium. Lucifer, with continuous dematerialization, results in continuous materialization: Ahriman. When we perceive, that is Lucifer. When we think about what we have perceived: Ahriman. When we form the idea, this or that we should want: Lucifer. When we really want on earth: Ahriman. So we are in the middle of the two. We oscillate back and forth between them, and we must be clear about ourselves: as human beings, we are placed in the most intimate way between the Ahrimanic and the Luciferic. Actually, you only get to know a person when you take these two opposing poles in him into account. This is an approach that is based neither on an abstract spiritual reality – for this abstract spiritual reality is, after all, nebulous and mystical – nor on a material one, but rather everything that is materially effective is also spiritual at the same time. We are dealing with the spiritual everywhere. And we see through matter in its existence, in its effectiveness, by being able to see the spirit in everything. I have already told you that imagination comes to us of its own accord in relation to the present. When we develop imagination artificially, we look into the past. When we develop inspiration, we look into the future, just as one calculates into the future by calculating solar or lunar eclipses, not in relation to the details, but to a higher degree in relation to the great laws of the future. And intuition encompasses all three. And we are actually subject to intuition all the time, we just sleep through it. When we sleep, we are completely immersed in the outside world with our ego and our astral body; there we unfold that intuitive activity that one must otherwise consciously unfold in intuition. But in this present organization the human being is too weak to be conscious when he is intuiting; but he does intuit in fact at night. So one can say: Asleep, the human being develops intuition; awake, he develops—to a certain extent, of course—logical thinking; between the two stands inspiration and imagination. When a person comes out of sleep into waking life, his I and his astral body enter into the physical body and the etheric body; what he brings with him is the inspiration to which I have already drawn your attention in previous lectures. We can say: Man is asleep in intuition, awake in logical thinking, when he wakes up he inspires himself, when he falls asleep he imagines. - You can see from this that the activities we mention as the higher activities of knowledge are not alien to ordinary life, but that they are very much present in ordinary life, that they only have to be raised into consciousness if a higher knowledge is to be developed. It must be pointed out again and again that in the last three to four centuries, external science has summarized a large number of purely material facts and brought them into laws. These facts must first be spiritually penetrated. But it is good - if I may say so, although it sounds paradoxical at first - that materialism was there, otherwise people would have fallen into nebulosity. They would have finally lost all connection with their earthly existence. When materialism began in the 15th century, humanity was in fact in danger of falling prey to Luciferic influences to a high degree, of being hollowed out more and more and more. That is when the Ahrimanic influences came from that time on. And in the last four or five centuries, the Ahrimanic influences have developed to a certain extent. Today they have become very strong and there is a danger that they will overshoot their target if we do not counter them with something that will effectively weaken them: if we do not counter them with the spiritual. But here it is important to develop the right feeling for the relationship between the spiritual and the material. In the older German way of thinking, there is a poem called “Muspilli”, which was first found in a book dedicated to Louis the German in the 9th century, but which of course dates from a much earlier time. There is something purely Christian in this poem: it presents us with the battle of Elijah with the Antichrist. But the whole way in which this story unfolds, this fight between Elijah and the Antichrist, is reminiscent of the ancient struggles of the sagas, the inhabitants of Asgard with the inhabitants of Jötunheim, the inhabitants of the realm of the giants. It is simply the realm of the Æsir transformed into the realm of Elijah, the realm of the giants into the realm of the Antichrist. This way of thinking, which we still encounter, conceals the true fact less than the later ways of thinking. The later ways of thinking always talk about duality, about good and evil, about God and the devil, and so on. But these ways of thinking, which were developed in later times, no longer correspond to the earlier ones. Those people who developed the struggle between the Gods' home and the giants' home did not see the same in the Gods as, for example, today's Christian understands in the realm of his God. Instead, these older ideas had, for example, Asgard, the realm of the Gods, above, and Jötunheim, the realm of the giants, below; in the middle, Man unfolds, Midgard. This is nothing other than the same thing in the Germanic-European way that was present in ancient Persia as Ormuzd and Ahriman. There we would have to say in our language: Lucifer and Ahriman. We would have to address Ormuzd as Lucifer and not just as the good God. And that is the great mistake that is made, that one understands this dualism as if Ormuzd were only the good God and his opponent Ahriman the evil God. The relationship is rather like that of Lucifer to Ahriman. And in Middlegard, at the time when this poem “Muspilli” was written, it is still not imagined that The Christ sends his blood down from above – but: Elijah is there, and sends his blood down. And man is placed in the middle. At the time when Louis the German probably wrote this poem into his book, the idea was still more correct than the later one. For later times have committed the strange act of disregarding the Trinity; that is, to understand the upper gods, who are in Asgard, and the lower gods, the giants, who are in the Ahrimanic realm, as the All, and to understand the upper, the Luciferic ones, as the good gods and the others as the evil gods. This was done in later times; in earlier times, this opposition between Lucifer and Ahriman was still properly envisaged, and therefore something like Elijah was placed in the Luciferic realm with his emotional prophecy, with that which he was able to proclaim at that time, because one wanted to place the Christ in Midgard, in that which lies in the middle. We must go back to these ideas in full consciousness, otherwise we will not come back to the Trinity: to the Luciferic Gods, to the Ahrimanic powers and in between to what the Christ-realm is. Without advancing to this, we will not come to a real understanding of the world. Do you think that the fact that the old Ormuzd was made into a good god, while he is actually a Luciferic power, a power of light, is a tremendous secret of the historical development of European humanity? But in this way one could have the satisfaction of making Lucifer as bad as possible; because the name Lucifer did not suit Ormuzd, one made Lucifer resemble Ahriman, made a hotchpotch that still has an effect on Goethe in the figure of Mephistopheles, in that there too Lucifer and Ahriman are mixed together, as I have explicitly shown in my little book 'Goethe's Spiritual Nature'. Indeed, European humanity, the humanity of present civilization, has entered into a great confusion, and this confusion ultimately permeates all thinking. It can only be compensated by leading out of duality back into trinity, because everything dual ultimately leads to something in which man cannot live, which he must regard as a polarity, in which he can now really find the balance: Christ is there to balance Lucifer and Ahriman, to balance Ormuzd and Ahriman, and so on.This is the topic I wanted to broach, and we will continue to discuss it in the coming days in various ways. |

| 205. Humanity, World Soul and World Spirit I: Twelfth Lecture

16 Jul 1921, Dornach Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| 205. Humanity, World Soul and World Spirit I: Twelfth Lecture

16 Jul 1921, Dornach Rudolf Steiner |

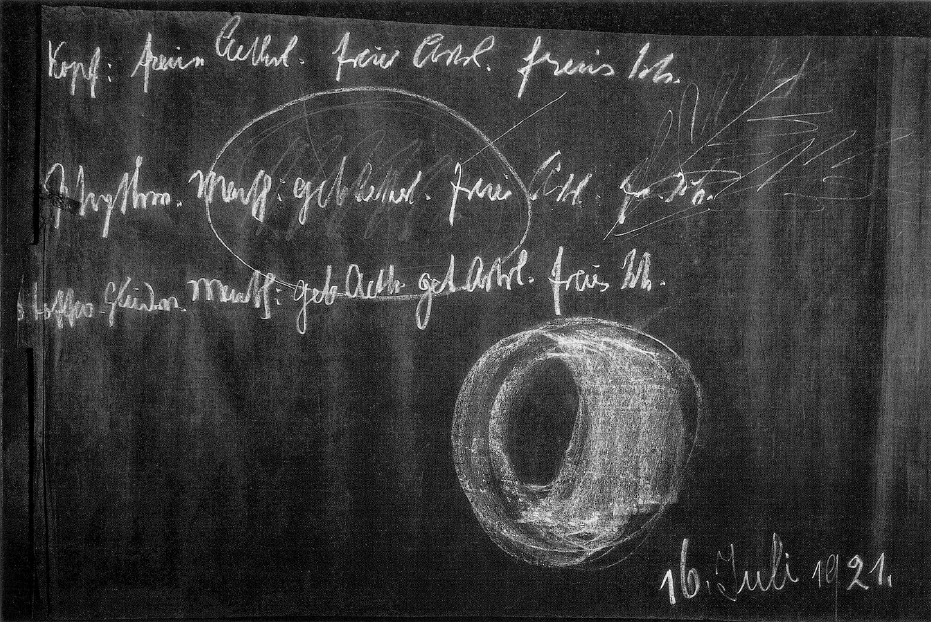

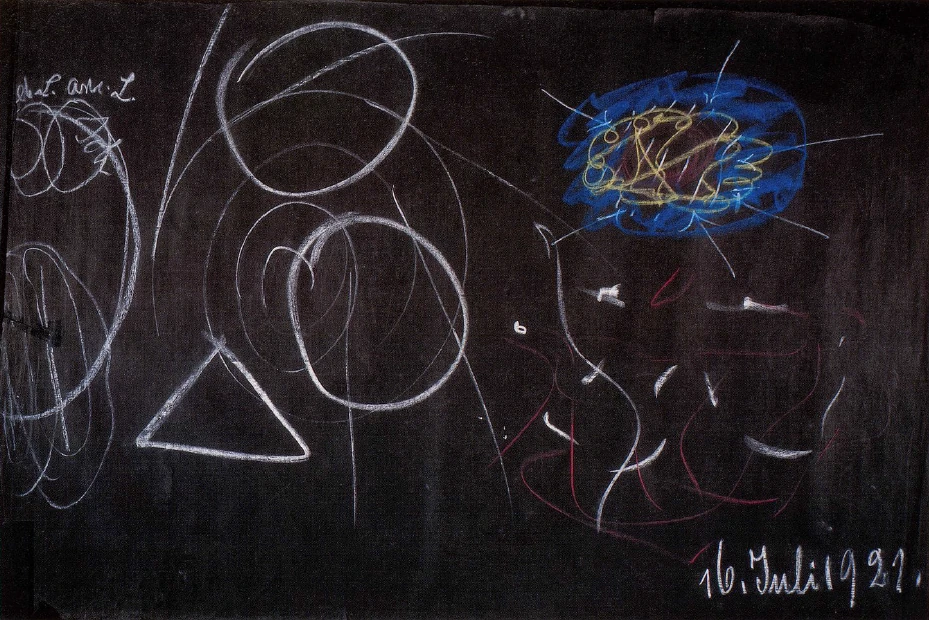

|---|