World History in the Light of Anthroposophy

and as a Foundation for Knowledge of the Human Spirit

GA 233

25 December 1923, Dornach

Lecture II

From the foregoing lecture it will be clear to you that it is only possible to gain a correct view of the historical evolution of humanity when one takes into consideration the totally different conditions of mind and soul that prevailed during the various epochs. In the first part of my lecture I attempted to define the Asiatic period of evolution, the genuine ancient East, and we saw that we have to look back to the time when the descendants of the races of Atlantis were finding their way eastwards after the Atlantean catastrophe, moving from west to east and gradually peopling Europe and Asia. All that took place in ancient Asia in connection with these peoples was under the influence of a condition of soul accustomed and attuned to rhythm. At the beginning of the Asiatic period we have still a distant echo of what was present in all its fullness in Atlantis—the localised memory. During the Oriental evolution this localised memory passed over into rhythmic memory, and I showed how with the Greek evolution that great change came about which brought in a new kind of memory, the temporal memory. This means that the Asiatic period of evolution (we are now speaking of what may rightly be called the Asiatic period, for what history refers to is in reality a later and decadent period) was an age of men altogether differently constituted from the men of later times. And the external events of history were in those days much more dependent than in later times on the character and constitution of man's inner life. What lived in man's mind and soul lived too in his entire being. A separated life of thought and feeling, such as we have to-day was unknown. A thinking that does not feel itself to be connected with the inner processes of the human head, was unknown. So too was the abstract feeling that knows no connection with the circulation of the blood. Man had in those times a thinking that was inwardly experienced as a “happening” in the head, a feeling that was experienced in the rhythm of the breath, in the circulation of the blood, and so on. Man experienced his whole being in undivided unity.

All this was closely connected with the altogether different experience man had of his relation to the world about him, to the Cosmos, to the spiritual and the physical in the Cosmic Whole. The man of the present day lives, let us say, in town or in the country, and his experience varies accordingly. He is surrounded by woods, rivers and mountains; or, if he lives in town, bricks and mortar meet his gaze on every hand. When he speaks of the cosmic and super-sensible, where does he think it is? He can point to no sphere within which he can conceive of what is cosmic and super-sensible as having place. It is nowhere to be laid hold of, he cannot grasp it: even spiritually, he cannot grasp it. But this was not so in that ancient oriental stream of evolution. To an Oriental, the world around him which we to-day call our physical environment, was the lowest portion of a Cosmos conceived as a unity. Man had around him what is contained in the three kingdoms of nature, he had around him the rivers, mountains, and so forth; but for him this environment was permeated through and through with Spirit, interpenetrated and interwoven with Spirit. The Oriental of ancient time would say: I live with the mountains, I live with the rivers; but I live also with the elemental beings of the mountains and of the rivers. I live in the physical realm, but this physical realm is the body of a spiritual realm. Around me is the spiritual world, the lowest spiritual world.

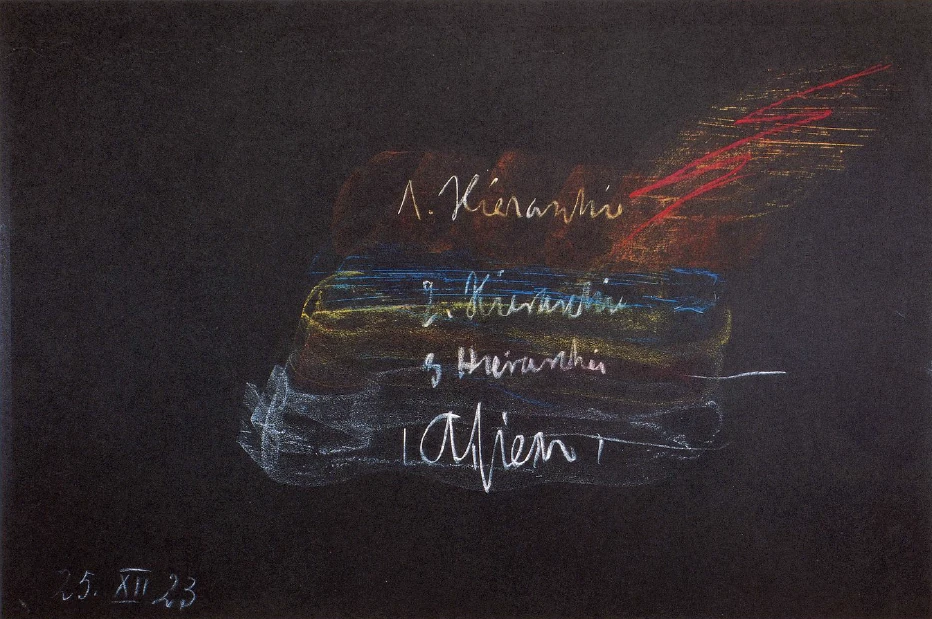

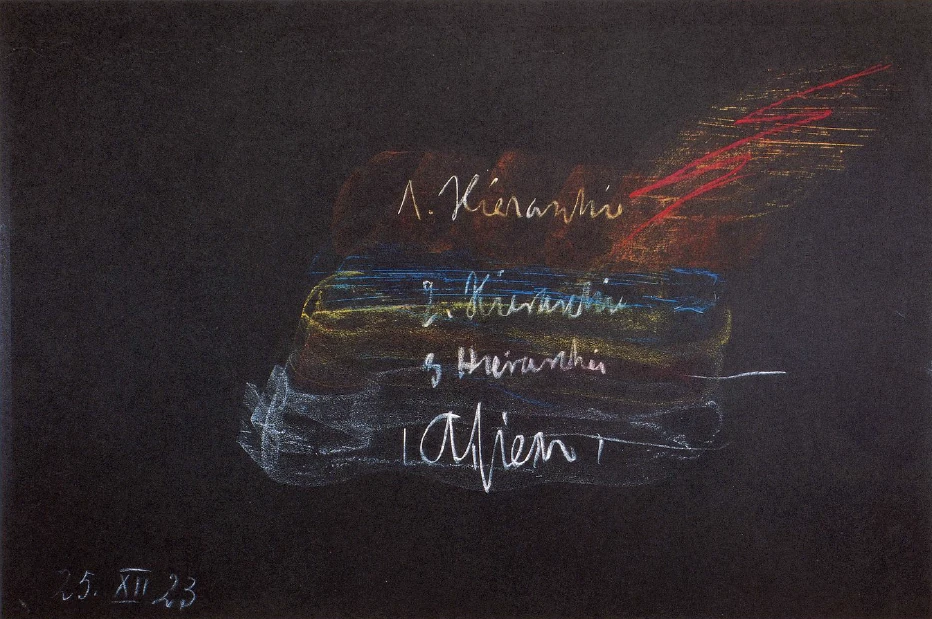

There below was this realm that for us has become the earthly realm. Man lived in it. But he pictured to himself that where this realm ends another realm begins, then again above that another; and finally the highest realm which it is possible to reach. And if we were to name these realms in accordance with the language that has become current with us in anthroposophical knowledge—the ancient Oriental had other names for them, but that does not matter, we will name them as they are for us—then we should have above, for the highest realm, the First Hierarchy: Seraphim, Cherubim, Thrones; then the Second Hierarchy: Kyriotetes, Dynamis, Exusiai; and the Third Hierarchy: Archai, Archangels, Angels.

And now comes the fourth realm where human beings live, the realm wherein according to our method of cognition we to-day place the mere objects and processes of Nature, but where the ancient Oriental felt the whole of Nature penetrated with the elemental spirits of water and of earth. This was Asia. Asia meant the lowest spirit realm, in which he, as human being, lived. You must remember that the present-day conception of things that we have in our ordinary consciousness was unknown to the man of those times. It would be nonsense to suppose that it were in any way possible for him to imagine such a thing as matter devoid of spirit. To speak as we do, of oxygen and nitrogen would have been a sheer impossibility for the ancient Oriental. To him oxygen was spirit, it was that spiritual thing which worked as a stimulating and quickening agent on what already possessed life, accelerating the life-processes in a living organism. Nitrogen, which we think of to-day as contained in the atmosphere together with oxygen, was also spiritual; it was that which weaves throughout the Cosmos, working upon what is living and organic in such a way as to prepare it to receive a soul-nature. Such was the knowledge the Oriental of old had, for example, of oxygen and nitrogen. And he knew all the processes of Nature in this way, in their connection with spirit; for the present-day conceptions were unknown to him. There were a few individuals who knew them, and they were the Initiates. The rest of mankind had as their ordinary everyday consciousness a consciousness very similar to a waking dream; it was a dream condition that with us only occurs in abnormal experiences.

The ancient Oriental went about with these dreams. He looked on the mountains, rivers and clouds, and saw everything in the way that things can be seen and heard in this dream condition. Picture to yourself what may happen to the man of to-day in a dream. He is asleep. Suddenly there appears before him a dream-picture of a flaring fire. He hears the call of ‘Fire!’ Outside in the street a fire engine is passing, to put out a fire somewhere or other. But what a difference between the conception of the work of the fire-brigade that can be formed by the human intellect in its matter-of-fact way with the aid of ordinary sense-perception, and the pictures that a dream can conjure up! For the ancient Oriental, however, all his experiences manifested themselves in such dream-pictures. Everything outside in the kingdoms of Nature was transformed in his soul into pictures.

In these dream-pictures man experienced the elemental spirits of water, earth, air and fire. And sleep brought him again other experiences. Sleep for him was not that deep heavy sleep we have when we lie, as we say, ‘like a log’ and know nothing of ourselves. I believe there are people who sleep so in these days, are there not? But then there was no such thing: even in sleep man had still a dull form of consciousness. While on the one hand he was, as we now say, resting his body, the spiritual was weaving within him in a spiritual activity of the external world. And in this weaving he perceived the Beings of the Third Hierarchy. Asia he perceived in his ordinary waking-dream condition, that is to say in what was the everyday consciousness of that time. At night, in sleep, he perceived the Third Hierarchy. And from time to time there entered into his sleep a still more dim and dark consciousness, but a consciousness that graved its experiences deeply into his thought and feeling. Thus these Eastern peoples had first their everyday consciousness where everything was changed into Imaginations and pictures. The pictures were not so real as those of still older times, for example the time of Atlantis or Lemuria, or of the Moon epoch. Nevertheless they were still there, even during this Asiatic evolution. By day, then, men had these pictures. And in sleep they had an experience which they might have clothed in the following words:—We ‘sleep away’ the ordinary earthly existence, we enter the realm of the Angels, Archangels and Archai and live among them. The soul sets itself free from the organism and lives among the Beings of the higher Hierarchies.

Men knew at the same time that whereas they lived in Asia with gnomes, undines, sylphs and salamanders, that is with the elemental spirits of the earth, water, air and fire,—in sleep, while the body rested, they experienced the Beings of the Third Hierarchy in the planetary existence, in all that lives in the whole planetary system belonging to the Earth.

There were however moments when the sleeper would feel: An utterly strange region is approaching me. It is taking me to itself, it is drawing me away from earthly existence. He did not feel this while immersed in the Beings of the Third Hierarchy, but only when a still deeper condition of sleep intervened. Though there was never a real consciousness of what took place during the sleep-condition of the third kind, nevertheless what was then experienced from the Second Hierarchy impressed itself deep into the whole being of man. And the experience remained in man's feeling when he awoke. He could then say: I have been graciously blessed by higher Spirits, whose life is beyond the planetary existence. Thus did these ancient peoples speak of that Hierarchy which embraces the Kyriotetes, the Dynamis and the Exusiai. What we are now describing are the ordinary states of consciousness of this ancient Asiatic period. The first two states of consciousness—the waking-sleeping, sleeping-waking and the sleep, in which the Third Hierarchy were present—were experienced by all men. And many, through a special endowment of Nature, experienced also the intervention of a deeper sleep, during which the Second Hierarchy played into human consciousness.

And the Initiates in the Mysteries,—they received a still further degree of consciousness. Of what nature was this? The answer is astonishing; for the fact is, the Initiate of the ancient East acquired the same consciousness that you have now by day! You develop it in a perfectly natural way in your second or third year of life. No ancient Oriental ever attained this state of consciousness in a natural way; he had to develop it artificially in himself. He had to develop it out of the waking-dreaming, dreaming-waking. As long as he went about with this waking-dreaming, dreaming-waking, he saw everywhere pictures, rendering only in more or less symbolic fashion what we see to-day in clear sharp outlines; as an Initiate however he attained to see things as we see them to-day in our ordinary consciousness. The Initiates, by means of their developed consciousness, attained to learn what every boy and girl learns at school to-day. The difference between their consciousness and the normal consciousness of to-day is not that the content was different. Of course the abstract forms of letters which we have to-day were unknown then; written characters were in more intimate connection with the things and processes of the Cosmos. Reading and writing were nevertheless learned in those days by the Initiates; although of course by them alone, for reading and writing can only be learned with that clear intellectual consciousness which is the natural one for the man of to-day.

Supposing that somewhere or other this world of the ancient East were to re-appear, inhabited by human beings having the kind of consciousness they had in those olden times, and you were to come among them with your consciousness of the present day, then for them you would all be initiates. The difference does not lie in the content of consciousness. You would be initiates. But the moment the people recognised you as initiates, they would immediately drive you out of the land by every means in their power; for it would be quite clear to them that an initiated person ought not to know things in the way we know them to-day. He ought not, for example, to be able to write as we are able to write to-day. If I were to transport myself into the mind of a man of that time, and were to meet such a pseudo-initiate, that is to say, an ordinary clever man of the present day, I should find myself saying of him: He can write, he makes signs on paper that mean something, and he has no idea how devilish it is to do such a thing without carrying in him the consciousness that it may only be done in the service of divine cosmic consciousness; he does not know that a man may only make such signs on paper when he can feel how God works in his hand, in his very fingers, works in his soul, enabling it to express itself through these letters. Therein lies the whole difference between the initiates of olden time and the ordinary man of the present day. It is not a difference in the content of consciousness, but in the way of comprehending and understanding the thing. Read my book Christianity as Mystical Fact, of which a new edition has recently appeared, and you will find right at the beginning the same indication as to the essential nature of the initiate of olden times. It is in point of fact always so in the course of world-evolution. That which develops in man at a later period in a natural way had in former epochs to be won through initiation.

Through such a thing as I have brought to your notice, you will be able to detect the radical difference between the condition of mind and soul prevalent among the Eastern peoples of prehistoric times and that of a later civilisation. It was another mankind that could call Asia the last or lowest heaven and understand by that their own land, the Nature that was round about them. They knew where the lowest heaven was.

Compare this with the conceptions men have to-day. How far is the man of the present time from regarding all he sees around him as the lowest heaven! Most people cannot think of it as the ‘lowest’ heaven for the simple reason that they have no knowledge of any heaven at all!

Thus we see how in that ancient Eastern time the Spiritual entered deeply into Nature, into all natural existence. But now we find also among these peoples something which to most of us in the present day may easily appear extremely barbarous. To a man of that time it would have appeared terribly barbarous if someone had been able to write in the feeling and attitude of mind in which we to-day are able to write; it would have seemed positively devilish to him. But when we to-day on the other hand see how it was accepted in those times as something quite natural and as a matter of course that a people should remove from West to East, should conquer—often with great cruelty—another people already in occupation and make slaves of them, then such a thing is bound to appear barbarous to very many of us.

This is, however, broadly speaking, the substance of oriental history over the whole of Asia. Whilst men had as I have described, a high spiritual conception of things, their external history ran its course in a series of conquests and enslavements. Undoubtedly that appears to many people as extremely barbarous. To-day, although wars of aggression do still sometimes occur, men have an uneasy conscience about them. And this is true even of those who support and defend such wars; they are not quite easy in their conscience.

In those times, however, man had a perfectly clear conscience as regards these wars of aggression, he felt that such conquest was willed of the Gods. The longing for peace, the love of peace, that arose later and spread over a large part of Asia, is really the product of a much later civilisation. The acquisition of land by conquest and the enslavement of its population is a salient feature of the early civilisation of Asia. The farther we go back into prehistoric times, the more do we find this kind of conquest going on. The conquests of Xerxes and others of his time were in truth but faint shadows of what went on in earlier ages.

Now there is a quite definite principle underlying these conquests. As a result of the states of consciousness which I have described to you, man stood in an altogether different relation to his fellow man and also to the world around him. Certain differences between different parts of the inhabited Earth have to-day lost their chief meaning. At that time these differences made themselves felt in quite another way. Let me put before you, as an example, something which frequently occurred.

Suppose a conquering people has made its way from the North of Asia, spread itself out over some other region of Asia and made the population subject to it. What has really happened?

In characteristic instances that are a true expression of the trend of historical evolution, we find that the aggressors were—as a people or as a race—young, full of youth-forces. Now what does it mean to-day to be young? What does it mean for men of our present epoch of evolution? It means to bear within one in every moment of life sufficient [amount] of the forces of death to provide for those soul-forces that need the dying processes in man. For, as you know, we have within us, the sprouting, germinating forces of life, but these life forces are not the forces that make us reflective, thoughtful beings; on the contrary, they make us weak, unconscious. The death forces, the forces of destruction, which are also continually active within us—and are overcome again and again during sleep by the life forces, so that not until the end of life do we gather together all the death forces in us in the one final event of death—these forces it is that induce reflection, self-consciousness. This is how it is with present-day humanity. Now a young race, a young people, such as I have described, suffered from its own over-strong life forces, and continually had the feeling: I feel my blood beating perpetually against the walls of my body. I cannot endure it. My consciousness will not become reflective consciousness. Because of my very youthfulness I cannot develop my full humanity.

An ordinary man would not have spoken thus, but the initiates spoke in this way in the Mysteries, and it was the initiates who guided and directed the whole course of history.

Here was then a people who had too much youth, too much life forces, too little in them of that which could bring about reflection and thought. They left their land and conquered a region where an older people lived, a people which had in some way or other taken into itself the forces of death, because it had already become decadent. The younger nation went out against the older and brought it into subjection. It was not necessary that a blood-bond should be established between conquerors and enslaved. That which worked unconsciously in the soul between them worked in a rejuvenating way; it worked on the reflective faculties. What the conqueror required from the slaves whom he now had in his court was influence upon his consciousness. He had only to turn his attention to these slaves and the longing for unconsciousness was quenched in his soul, reflective consciousness began to dawn.

What we have to attain to-day as individuals was attained at that time by living together with others. A people who faced the world as conquerors and lords, a young people, not possessed of full powers of reflection, needed around it, so to say, a people that had in it more of the forces of death. In overcoming another people, it won through to what it needed for its own evolution.

And so we find that these Oriental conflicts, often so terrible and presenting to us such a barbarous aspect, are in reality nothing else than the impulses of human evolution. They had to take place. Mankind would not have been able to develop on the earth, had it not been for these terrible wars and struggles that seem to us so barbarous.

Already in those olden times the Initiates of the Mysteries saw the world as it is seen to-day. Only they united with this perception a different attitude of mind and soul. For them, all that they experienced in clear, sharp outlines—even as we to-day experience external objects in sharp outlines, when we perceive with our senses—was something that came from the Gods, that came even for human consciousness from the Gods. For how did external objects present themselves to an Initiate of those times? There was perhaps a flash of lightning (to take a simple and obvious illustration). You know very well what a flash of lightning looks like to a man of to-day. The men of olden time did not see it thus. They saw living spiritual Beings moving in the sky, and the sharp line of the flash disappeared completely. They saw a host, a procession of spiritual Beings hurrying forward over or in cosmic space. The lightning as such they did not see. They saw a host of spirits hovering and moving through cosmic space.

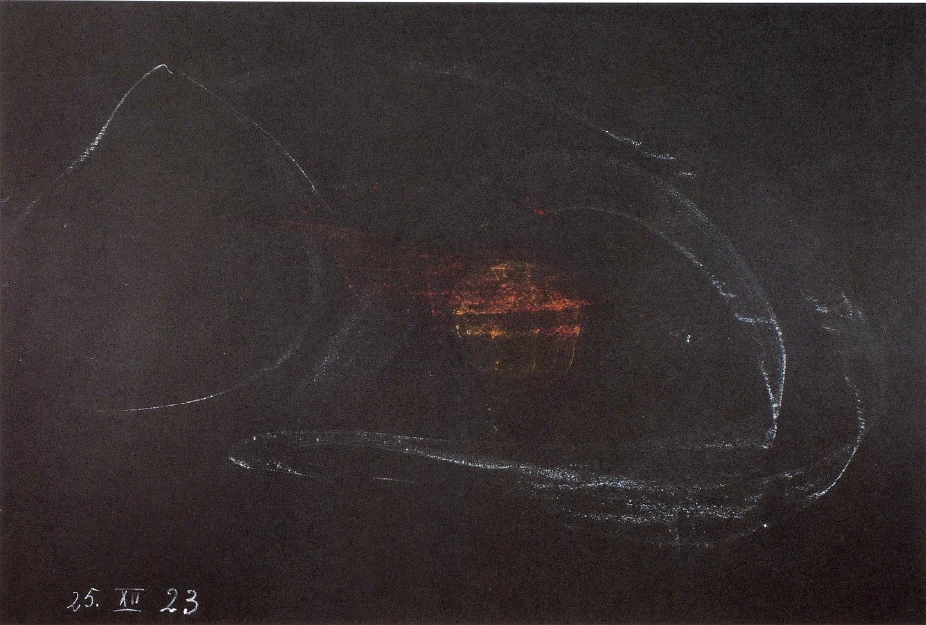

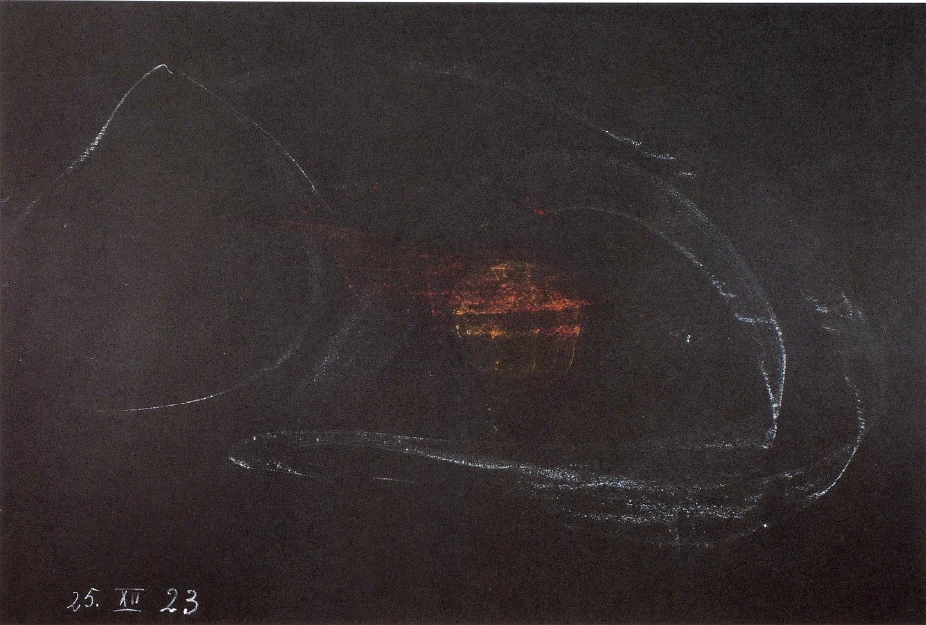

The Initiate also saw, with the rest, this spiritual host, but he had developed within him the perception that we have to-day, and so for him, the picture began to grow dim and the heavenly host gradually disappeared from view, and then the flash of lightning could become manifest.

The whole of Nature, in the form in which we see it to-day, could only be attained in olden times through initiation. But how did man feel towards such knowledge? He did not by any means look on the knowledge thus attained with the indifference with which knowledge and truth are regarded to-day. There was a strong moral element in man's experience of knowledge. If we turn our gaze to what happened with the neophytes of the Mysteries, we find we have to describe it in the following way. When a few individuals, after undergoing severe inner tests and trials, had been initiated into the view of Nature, which to-day is accessible to all, they had quite naturally this feeling: consider the man with his ordinary consciousness. He sees the host of elementary beings riding through the air. But just because he has such a perception, he is devoid of free will. He is entirely given up to the Divine-spiritual world. For in this waking-dreaming, dreaming-waking, the will does not move in freedom, rather is it something that streams into man as Divine will. And the Initiate, who saw the lightning come forth out of these Imaginations, learned to say: I must be a man who is free to move in the world without the Gods, one for whom the Gods cast out the world-content into the void.

Now you must understand, this condition would have been unbearable for the Initiate, had there not been for him moments that compensated for it. Such moments he did have. For while on the one hand the Initiate learned to experience Asia as God-forsaken, Spirit-forsaken, he learned also to know a still deeper state of consciousness than that which reached up to the Second Hierarchy. Knowing the world bereft of God, he learned also to know the world of the Seraphim, Cherubim and Thrones.

At a certain time in the epoch of Asiatic evolution, approximately in the middle [of it]—later on we shall have to speak more exactly of the dates—the condition of consciousness of the Initiates was such that they went about on Earth with very nearly the perception of the kingdoms of the Earth which is possessed by modern man; they felt it, however, in their limbs. They felt their limbs set free from the Gods in a God-bereft earthly substance.

In compensation for this, however, they met in this godless land the high Gods of the Seraphim, Cherubim and Thrones. As Initiates they learned to know, no longer the grey-green spiritual Beings that were the Pictures of the forest, the Pictures of the trees, they learned as Initiates to know the forest devoid of Spirit. Theirs, however, was the compensation of meeting in the forest Beings of the First Hierarchy, there they would meet some Being from the Kingdom of the Seraphim, Cherubim and Thrones.

All this, understood as giving form to the social life of humanity, is the essential feature in the historical evolution of the ancient East. And the driving force for further evolution lies in the search for an adjustment between young races and old races, so that the young races may mature through association with the old, with the souls of those whom they have brought into subjection. However far back we look into Asia, everywhere we find how the young races who cannot of themselves develop the reflective faculties, set out to find these in wars of aggression.

When, however, we turn our gaze away from Asia to the land of Greece, we find a somewhat different development. Over in Greece, in the time of the full flower of Greek culture, we find a people who did indeed know how to grow old, but were unable to permeate the growing old with full spirituality. I have many times had to draw attention to the characteristic Greek utterance: Better a beggar in the world of the living than a king in the realm of the shades. Neither to death outside in Nature, nor to death in man, could the Greek adapt himself. He could not find his true relation with death. On the other hand, however, he had this death within him. And so in the Greek we find, not a longing for a reflective consciousness, but apprehension and fear of death.

Such a fear of death was not felt by the young Eastern races; they went out to make conquests, when as a race they found themselves unable to experience death in the right way. The inner conflict, however, which the Greeks experienced with death became in its turn an inner impulse compelling humanity, and led to what we know as the Trojan War. The Greeks had no need to seek death at the hands of a foreign race in order to acquire the power of reflection. The Greeks needed to come into a right relation with what they felt and experienced of death, they needed to find the inner living mystery of death. And this led to that great conflict between the Greeks and the people in Asia from whom they had originated. The Trojan war is a war of sorrow, a war of apprehension and fear. We see facing one another the Greeks, who felt death within them but did not know, as it were, what to do with it, and the Oriental races who were bent on conquest, who wanted death and had it not. The Greeks had death, but were at a loss how to adapt themselves to it. They needed the infusion of another element, before they could discover its secret. Achilles, Agamemnon—all these men bore death within them, but could not adapt themselves to it. They look across to Asia. There in Asia they see a people who are in the reverse position, who are suffering under the direct influence of the opposite condition. Over there are men who do not feel death in the intense way it is felt by the Greeks themselves, over there are men to whom death is something abounding in life.

All this has been brought to expression in a wonderful way by Homer. Wherever he sets the Trojans over against the Greeks, everywhere he lets us see this contrast. You may see it, for instance, in the characteristic figures of Hector and Achilles. And in this contrast is expressed what is taking place on the frontier of Asia and Europe. Asia, in those olden times, had, as it were, a superabundance of life over death, yearned after death. Europe had, on the Greek soil, a superabundance of death in man, and man was at a loss to find his true relation to it. Thus from a second point of view we see Europe and Asia set over against one another.

In the first place, we had the transition from rhythmic memory to temporal memory; now we have these two quite different experiences in respect of death in the human organisation. To-morrow we will consider more in detail the contrast, which I have only been able to indicate at the close of to-day's lecture, and so approach a fuller understanding of the transitions that lead over from Asia to Europe. For these had a deep and powerful influence on the evolution of man, and without understanding them we can really arrive at no understanding of the evolution we are passing through at the present day.

Zweiter Vortrag

Aus den gestrigen Darstellungen wird Ihnen hervorgegangen sein, wie man eine richtige Anschauung über den geschichtlichen Verlauf der Menschenentwickelung auf der Erde nur dadurch bekommen kann, daß man sich einläßt auf die durchaus verschiedenen Seelenzustände, die vorhanden waren in den verschiedenen Zeitaltern. Und ich versuchte ja gestern zu begrenzen die eigentliche altorientalische, die asiatische Entwickelung, versuchte hinzuweisen auf jenen Zeitabschnitt, in dem die Nachkommen der atlantischen Bevölketung nach der atlantischen Katastrophe ihren Weg herübergefunden haben vom Westen nach dem Osten und nach und nach Europa, Asien bevölkert haben. Dasjenige, was dann dutch diese Völkerschaften in Asien abläuft, es stand ja ganz unter dem Einflusse eines Gemütszustandes dieser Menschen, der an das Rhythmische gewöhnt war. Im Beginne haben wir noch die Nachklänge, die deutlichen Nachklänge desjenigen, was ja in der Atlantis vollständig vorhanden war: das lokalisierte Gedächtnis. Dann geht es während der orientalischen Entwickelung in das ryhthmische Gedächtnis über. Und ich zeigte Ihnen ja, wie mit der griechischen Entwickelung erst der Umschwung zum Zeitgedächtnis eintritt.

Damit aber ist die eigentliche asiatische Entwickelung - denn das, was die Geschichte darstellt, sind ja schon Dekadenzzustände diejenige ganz andersgearteter Menschen, als es die Menschen späterer Zeit sind, und die äußeren geschichtlichen Geschehnisse sind in jenen alten Zeiten viel mehr abhängig von dem, was im Menschengemüte lebte, als später. Was in jenen älteren Zeiten im Menschengemüte lebte, das lebte eben im ganzen Menschen. Man kannte nicht ein so abgesondertes Seelen- und Denkleben wie heute. Man kannte nicht dieses Denken, das gar keinen Zusammenhang mehr fühlt mit den inneren Vorgängen des menschlichen Hauptes. Man kannte nicht dieses abstrakte Fühlen, das gar nicht mehr sich im Zusammenhang weiß mit der Blutzirkulation, sondern man kannte nur ein Denken, das man zu gleicher Zeit innerlich als Geschehen des Hauptes erlebte, ein Fühlen, das man erlebte im Atmungs- und Blutrhythmus und so weiter. Man erlebte, man empfand den ganzen Menschen in ungetrennter Einheit.

Das alles war aber damit verbunden, daß man auch das Verhältnis zur Welt, zum Weltenall, zum Kosmos, zum Geistigen und Physischen im Kosmos ganz anders erlebte als später. Der heutige Mensch erlebt sich auf Erden mehr oder weniger auf dem Lande oder in Städten. Er ist umgeben von dem, was er als Wälder anschaut, als Flüsse, als Berge, oder er ist umgeben von dem, was Gemäuer der Städte ist. Und wenn er von dem Kosmisch-Übersinnlichen spricht, ja, wo ist es denn eigentlich? Der moderne Mensch weiß ja sozusagen keine Sphäre anzugeben, wo er das Kosmisch-Übersinnliche sich denken soll. Es ist nirgends eigentlich für ihn greifbar, faßbar, ich meine auch nicht seelisch-geistig greifbar, faßbar. Das war so nicht in jener alten orientalischen Entwickelung, sondern in jener alten orientalischen Entwickelung war eigentlich die Umgebung, die wir heute als physische Umgebung bezeichnen würden, nur die unterste Partie einer einheitlich gedachten Welt. Da war um den Menschen herum dasjenige, was in den drei Naturreichen enthalten ist, was in Fluß und Berg und so weiter enthalten ist, aber das war zu gleicher Zeit geistdurchwachsen, wenn ich so sagen darf, geistdurchströmt, geistdurchwoben. Und der Mensch sagte: Ich lebe mit Bergen, ich lebe mit Flüssen, aber ich lebe auch mit den Elementargeistern der Berge, der Flüsse. Ich lebe im physischen Reich, aber dieses physische Reich ist der Körper eines geistigen Reiches. Um mich herum ist überall die geistige Welt, die unterste geistige Welt.

Da war dieses Reich, das nun für uns das irdische geworden ist, unten. Der Mensch lebte darinnen. Aber er stellte sich eben in seinem Bilde vor (siehe Zeichnung), daß, wo dieses Reich (hell) nach oben hin aufhört, eben ein anderes beginnt (gelb-rot), in welches das untere übergeht, und dann wieder ein anderes (blau), und zuletzt das höchste, das noch zu erreichen ist (orange). Und wenn wir nach dem, was unter uns in der anthroposophischen Erkenntnis üblich geworden ist, diese Reiche benennen wollten - im alten orientalischen Leben hatten sie andere Namen, aber das kommt nicht darauf an, wir wollen sie so benennen, wie sie für uns heißen -, so würden wir da oben die erste Hierarchie haben: Seraphim, Cherubim, Throne, dann die zweite Hierarchie: Kyriotetes, Dynamis, Exusiai, und die dritte Hierarchie: Archai, Archangeloi, Angeloi.

Und nun kam das vierte Reich, wo die Menschen drinnen leben, wo wir heute nach unserer Erkenntnis nur die Naturgegenstände und Naturvorgänge ansetzen, wo diese Menschen die Naturvorgänge und Naturdinge durchwoben fühlten von den Elementargeistern des Wassers, der Erde. Und das war Asien (siehe Zeichnung).

Asien bedeutete das unterste Geisterreich, in dem man als Mensch noch darinnen ist. Allerdings, was heute unsere gewöhnliche Anschauung ist, die der Mensch für sein gewöhnliches Bewußtsein hat, das hatte man in jenen alten orientalischen Zeiten nicht. Es wäre ganz unsinnig zu denken, daß man in jenen alten orientalischen Zeiten die Möglichkeit gehabt hätte, geistlose Materie irgendwo zu vermuten. Was wir heute reden von Sauerstoff, Stickstoff, es wäre ja für jene alten Zeiten zu denken die reine Unmöglichkeit gewesen. Sauerstoff war das Geistige, das belebend, erregend wirkte auf das schon Lebendige, das beschleunigend auf das Leben des Lebendigen wirkte. Stickstoff, den wir heute uns so vorstellen, daß er dem Sauerstoff beigemengt in der Luft enthalten ist, Stickstoff war jenes Geistige, das die Welt durchwebt und das, indem es auf das lebendige Organische wirkt, dieses Organische bereitmacht, in sich Seelisches aufzunehmen. Nur so kannte man zum Beispiel Sauerstoff und Stickstoff. Und so kannte man alle Naturvorgänge als im Zusammenhange mit Geistigem, weil man die Anschauung, die man heute als Mann auf der Straße hat, gar nicht hatte. Einzelne hatten sie, und das waren gerade die Eingeweihten, die Initiierten. Die anderen Menschen hatten für das gewöhnliche Alltägliche einen Bewußtseinszustand, der sehr ähnlich ist einem Wachtraum, aber eben ein Traumzustand, wie er bei uns nur noch in abnormen Erlebnissen vorhanden ist. Mit diesem Träumen ging der Mensch herum. Mit diesem Träumen ging er an die Wiesen, an die Bäume, an die Flüsse heran, an die Wolken, und er sah alles in dieser Weise, wie man es sehen und hören kann in diesem Traumzustande.

Sie müssen sich nur einmal vorstellen, was da zum Beispiel geschehen kann für den heutigen Menschen. Der Mensch ist eingeschlummert. Plötzlich tritt vor ihm auf das Bild, das Traumesbild eines feurigen Ofens. Er hört: Feurio! Draußen fährt die Feuerwehr vorbei, um irgendwo ein Feuer zu löschen. - Wie weit verschieden ist dasjenige, was trocken die menschliche Vernunft, wie man sagt, und das gewöhnliche sinnliche Anschauen von diesem Tun der Feuerwehr vernehmen, von dem, was der Traum dem Menschen vorspiegeln kann. Aber so in Träume gegossen war alles das, was jene alte orientalische Menschheit erlebte. Da verwandelte sich alles, was draußen in den Reichen der Natur war, in Bilder. Und in diesen Bildern erlebte man die Elementargeister des Wassers, der Erde, der Luft, des Feuers. Und jener Plumpsackschlaf, den wir haben - ich meine, jener Schlaf, wo man eben ganz daliegt wie ein Sack und gar nichts von sich weiß -, den hatten die Menschen in damaliger Zeit nicht. Nicht wahr, diesen Schlaf gibt es doch heute. Den hatten aber die Menschen in der damaligen Zeit nicht, sondern sie hatten auch während dieses Schlafes ein dumpfes Bewußtsein. Während sie auf der einen Seite, wie wir es heute nennen, ihren Körper ausruhten, wob das Geistige in ihnen in einem Tätigsein der äußeren Welt. Und in diesem Weben nahm man wahr dasjenige, was die dritte Hierarchie ist. Asien nahm man wahr im gewöhnlichen Wach-Traumzustande, das heißt in dem alltäglichen Bewußtsein von damals. Die dritte Hierarchie nahm man wahr im Schlafe. Und in den Schlaf tauchte dann zuweilen ein noch dumpfes Bewußtsein ein, aber ein Bewußtsein, welches seine Erlebnisse tief in das Menschengemüt hineingrub. So daß es also für diese orientalische Bevölkerung dieses Alltagsbewußtsein gab, wo alles sich in Imaginationen und Bilder wandelte. Sie waren nicht so real, wie jene der älteren Zeit, zum Beispiel der atlantischen oder gar der lemurischen Zeit oder der Mondenzeit, aber es waren immerhin Bilder, die da noch vorhanden waren auch während dieser orientalischen Entwickelung.

Also diese Menschen hatten diese Bilder. Dann hatten sie in den Schlafzuständen dasjenige, was sie in die Worte kleiden konnten: Entschlummern wir dem gewöhnlichen irdischen Dasein, dann treten wir ein in das Reich der Angeloi, Archangeloi, Archai und leben unter ihnen. Die Seele macht sich frei vom Organismus und lebt unter den Wesen der höheren Hierarchien.

Zu gleicher Zeit war man sich klar darüber, daß, während man in Asien lebte, mit Gnomen, Undinen, Sylphen, Salamandern, das heißt mit den Elementargeistern der Erde, des Wassers, der Luft, des Feuers, daß man in dem Schlafzustand, in dem der Körper sich ausruhte, erlebte die Wesenheiten der dritten Hierarchie, aber zu gleicher Zeit erlebte mit dem planetarischen Dasein, mit demjenigen, was in dem Planetensystem lebt, das zur Erde gehört. - Dann aber trat manchmal herein in das Schlafbewußtsein, wo man die dritte Hierarchie wahrnahm, ein ganz besonderer Zustand, in dem der Schlafende fühlte: Es kommt ein ganz fremdes Bereich an mich heran. Es nimmt mich etwas an sich, es holt mich etwas weg aus dem irdischen Dasein. Das fühlte man noch nicht, indem man in die dritte Hierarchie vetsetzt war, aber indem dieser tiefere Schlafzustand kam, fühlte man dieses. Eigentlich war niemals ein deutliches Bewußtsein davon vorhanden, was während dieses Schlafzustandes der dritten Art geschah. Aber tief, tief bohrte sich ein in das ganze menschliche Sein dasjenige, was da erlebt wurde aus der zweiten Hierarchie heraus. Und der Mensch hatte es bei seinem Aufwachen in seinem Gemüte, und er sagte: Ich bin begnadet worden von höheren Geistern, die über dem planetarischen Dasein ein Leben haben. - Und so sprachen diese Menschen dann von jener Hierarchie, welche die Exusiai, die Kyriotetes und die Dynamis umfaßt. - Und dieses, was ich Ihnen jetzt erzähle, das war sozusagen im älteren Asien im Grunde das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein. Die zwei Bewußtseinszustände, das Wachend-Schlafen, Schlafend-Wachen, und den Schlaf, in den die dritte Hierarchie hereinragte, das hatten schon von vornherein alle. Und manche hatten durch ihre besondere Naturanlage dann dieses Hereinragen eines tieferen Schlafes, wo die zweite Hierarchie in das menschliche Bewußtsein hereinspielte. Und die Eingeweihten in den Mysterien, sie bekamen einen weiteren Bewußtseinszustand. Welchen? Das ist eben gerade das Übertaschende. Wenn man die Antwort darauf gibt: Welchen Bewußtseinszustand bekamen nun die Eingeweihten der damaligen Zeit? -, so lautet sie: Den Bewußtseinszustand, den Sie heute am Tage immer haben. - Sie entwickeln ihn in Ihrem zweiten, dritten Lebensjahre auf natürliche Weise. Der alte Orientale ist auf natürliche Weise nie dazu gekommen, sondern er mußte ihn künstlich heranbilden. Er mußte ihn heranbilden aus dem wachenden Träumen, träumenden Wachen. Während er, wenn er herumging mit seinem wachenden Träumen, träumenden Wachen, Bilder überall sah, die mehr oder weniger symbolisch nur dasjenige gaben, was wir heute mit scharfen Konturen sehen, kamen die Eingeweihten dazu, die Dinge dazumal so zu sehen, wie sie der Mensch heute mit dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein alle Tage sieht. Und die Eingeweihten kamen dazumal dazu, dutch dieses erst heranentwickelte Bewußtsein das zu lernen, was heute jeder Schulknabe und jedes Schulmädchen in der Volksschule lernt. Und der Unterschied bestand nicht darin, daß der Inhalt etwas anderes war. Allerdings jene abstrakten Buchstabenformen, die wir heute haben, die hatte man damals nicht. Die Schrift wies Charaktere auf, welche in innigerem Zusammenhange mit den Sachen und Vorgängen der Welt standen. Aber immerhin, das Schreiben, das Lesen lernten in diesen alten Zeiten nur die Eingeweihten, weil man schreiben und lesen eben nur lernen kann in dem verstandesmäßigen Bewußtseinszustand, der heute der natürliche ist.

Wenn Sie sich also vorstellen würden, daß irgendwo wiederum auftreten würde diese altorientalische Welt mit Menschen jener Art, wie sie damals waren, und Sie unter diese Menschen treten würden mit Ihrer Seelenartung von heute, so wären Sie für jene Menschen dazumal alle Eingeweihte. Der Unterschied liegt eben nicht im Inhaltlichen. Sie wären Eingeweihte, aber Sie würden von den Menschen der damaligen Zeit in dem Augenblicke, wo Sie als Eingeweihte erkannt würden, mit allen möglichen Mitteln aus dem Lande getrieben werden, weil die Leute sich darüber klar wären, daß man als Eingeweihter die Dinge nicht so wissen darf, wie die heutigen Menschen sie wissen. Man darf zum Beispiel - das war die Anschauung der damaligen Zeit, ich charakterisiere sie durch dieses Bild nicht schreiben können, nach der Ansicht der damaligen Leute, wie die Menschen der heutigen Zeit schreiben können. Wenn ich mich hineinversetze in ein Gemüt der damaligen Zeit und es träte einem ein solcher Pseudoeingeweihter, das heißt ein gewöhnlicher Mensch, ein gewöhnlich gescheiter Mensch der Gegenwart entgegen, so würde dieser Mensch der damaligen Zeit sagen: Der kann schreiben, er macht Zeichen auf das Papier, die etwas bedeuten, und er ist sich nicht einmal bewußt, wie unendlich teuflisch es ist, so etwas zu tun und nicht das Bewußtsein in sich zu tragen, daß man dies nur im Auftrage des göttlichen Weltbewußtseins tun darf, daß man Zeichen, die etwas bedeuten, auf das Papier nur machen darf, wenn man sich bewußt ist: Der Gott wirkt in den Händen, in den Fingern, der Gott wirkt in der Seele, so daß die Seele sich ausdrückt durch diese Buchstabenformen. - Dieses, das nicht in der Verschiedenheit des Inhaltes liegt, das in der menschlichen Auffassung der Sache liegt, das ist es, was eben die Eingeweihten der alten Zeit noch ganz anders hatten als die heutigen Menschen, welche dasselbe inhaltlich haben. Sie werden, wenn Sie in meiner Schrift «Das Christentum als mystische Tatsache», die jetzt wiederum in Neuauflage erschienen ist, nachlesen, gleich im Anfange angedeutet finden, daß darinnen eigentlich das Wesen des Eingeweihten der alten Zeit lag. Und es ist eigentlich immer so in der Weltenentwickelung: Was in einer späteren Zeit auf natürliche Art in dem Menschen erwächst, das ist in einer früheren Zeit durch die Einweihung zu erringen. Gerade indem ich so etwas darstelle, werden Sie den gründlichen Unterschied verspüren zwischen der Gemütslage dieser alten orientalischen Völker der vorhistorischen Entwickelung und den Menschen, die später in die Zivilisation eingetreten sind. Es ist schon eine andere Menschheit, die den untersten Himmel Asien nannte und das eigene Land darunter verstand, die Natur, die einen umgab. Man wußte, wo der letzte Himmel ist. Vergleichen Sie das mit den Anschauungen von heute, wie wenig die Menschen der Gegenwart dasjenige, was sie umgibt, als den letzten Himmel betrachten. Die meisten können ihn ja nicht als den letzten betrachten, weil sie die vorhergehenden auch nicht kennen. Nun, wir sehen also, daß das Geistige bis tief in das Naturdasein hereinragt in dieser alten Zeit. Und dennoch, wir treffen etwas unter diesen Menschen wiederum, das uns in der gegenwärtigen Zeit unendlich barbarisch erscheinen möchte, wenigstens vielen von uns. Den Menschen dazumal wäre es furchtbar barbarisch erschienen, wenn jemand so hätte schreiben können, mit solcher Gesinnung, wie man heute schreiben kann. Es wäre ihnen überhaupt teuflisch erschienen. Einer großen Anzahl von Menschen der Gegenwart erscheint es aber ganz gewiß wiederum barbarisch, wie in jenem Asien drüben es etwas ganz Selbstverständliches war, daß eine Völkerschaft, die von Westen nach dem Osten weiter hinüberzog, oftmals mit großer Grausamkeit eine andere, die schon seßhaft war, sich untertan machte, deren Land eroberte, die Bevölkerung zu Sklaven machte. Das ist überhaupt im weiteren Umfange der Inhalt dieser orientalischen Geschichte über ganz Asien. Während diese Menschen eine hohe spirituelle Anschauung hatten in der Art, wie ich es eben charakterisiert habe, verlief die äußere Geschichte in fortwährenden Eroberungen fremden Landes, deren Bevölkerung untertänig gemacht worden ist. Das erscheint gewiß vielen Menschen in der Gegenwart wiederum barbarisch. Und wenn heute auch noch irgendwie Eroberungskriege vorhanden sind, so hat man doch dabei, selbst diejenigen, die sie verteidigen, nicht ein ganz gutes Gewissen. Man merkt das den Verteidigungen der Eroberungskriege schon an: man hat nicht ein ganz gutes Gewissen dabei. In der damaligen Zeit hatte man gerade gegenüber den Eroberungskriegen das allerbeste Gewissen, und man fand, daß dieses Erobern überhaupt gottgewollt ist. Und dasjenige, was dann später als die Friedenssehnsuchten über einen großen Teil Asiens sich ausgebreitet hatte, das ist eigentlich Spätprodukt der Zivilisation. Dagegen ist Frühprodukt der Zivilisation für Asien das fortwährende Erobern von Ländern und Untertänigmachen der Bevölkerungen. Je weiter man in die vorhistorischen Zeiten zurückschaut, desto mehr findet man dieses Erobern, von dem nur ein Schatten noch dasjenige ist, was Xerxes und ähnliche Leute getan haben.

Aber diesem Prinzip der Eroberungen liegt ja etwas ganz Bestimmtes zugrunde. In der damaligen Zeit war eben durch jene Bewußtseinszustände bei den Menschen, die ich Ihnen geschildert habe, der Mensch auch im Verhältnis zu den anderen Menschen und zur Welt in einer ganz anderen Lage als heute. Gewisse Unterschiede in den Bevölkerungsteilen der Erde haben heute ihre prinzipielle Bedeutung verloren. Dazumal waren sie in einer ganz anderen Weise vorhanden als heute. Und so wollen wir einmal etwas, was oftmals real war, als Beispiel vor unsere Seele hinstellen.

Nehmen wir an, wir hätten hier links das europäische Gebiet (Zeichnung Seite 36), hier rechts das asiatische Gebiet. Eine erobernde Bevölkerung (rot) konnte, auch vom Norden von Asien, herüberkommen, dehnt sich über irgendein Gebiet in Asien aus, macht die Bevölkerung untertan (rot um gelb).

Was lag da eigentlich vor? In den charakterisierten Fällen, welche die eigentliche geschichtliche Entwickelung im Fluß erhielten, war immer die Bevölkerung, die erobernd auftrat, als Volk oder als Rasse jung - jung, voller Jugendkraft. Nun, was heißt heute unter den Menschen der gegenwärtigen Erdenentwickelung jung sein? Unter den Menschen der gegenwärtigen Erdenentwickelung heißt jung sein, so viel Todeskräfte in jedem Augenblick seines Lebens in sich tragen, daß man die Seelenkräfte, die die absterbenden Vorgänge des Menschen brauchen, versorgen kann. Wir haben ja die sprießenden, sprossenden Lebenskräfte in uns; die machen uns aber nicht besonnen, sondern die machen uns gerade ohnmächtig, bewußtlos. Die abbauenden, die Todeskräfte, die fortwährend in uns auch wirken, die nur immer von den Lebenskräften während des Schlafes überwunden werden, so daß wir eben nur am Ende des Lebens zusammenfassen all die Todeskräfte in dem einmaligen Tode, diese Todeskräfte müssen fortwährend in uns sein. Die bewirken die Besonnenheit, das Bewußtsein. Das ist aber eben ein Charakteristikum der gegenwärtigen Menschheit. Solch eine junge Rasse, ein junges Volk, das litt an seinen überstarken Lebenskräften. Was da Mensch war, hatte fortwährend das Gefühl: Ich drücke dauernd mein Blut gegen meine Körperwände. Ich kann es nicht aushalten. Mein Bewußtsein will nicht besonnen werden. Ich kann meine volle Menschlichkeit wegen meiner Jugendlichkeit nicht entwickeln.

So sprachen allerdings nicht die gewöhnlichen Menschen, so sprachen aber die Eingeweihten in den Mysterien, die diese ganzen geschichtlichen Vorgänge dazumal noch leiteten und lenkten. Und so hatte eine solche Bevölkerung zuviel Jugend, zuviel Lebenskräfte, zuwenig von dem in sich, was Besonnenheit geben konnte. Dann zog sie aus, eroberte ein Gebiet, wo eine ältere Bevölkerung lebte, die schon in irgendeiner Weise Todeskräfte in sich aufgenommen hatte, weil sie bereits in die Dekadenz gekommen war, zog aus, machte sich diese Bevölkerung untertänig. Es brauchte nicht eine Blutsverwandtschaft einzutreten zwischen den Eroberern und den zu Sklaven Gemachten. Dasjenige, was sich unbewußt im Seelischen abspielte zwischen den Eroberern und den versklavten Leuten, das wirkte verjüngend, und auf die Besonnenheit hin wirkte es. Und der erobernde Mensch, der sich seinen Hof begründet hatte, wo er nun seine Sklaven hatte, er brauchte eben auch nur den Einfluß auf sein Bewußtsein. Er brauchte nur hinzulenken seinen Sinn auf diese Sklaven, und, ich möchte sagen, abgedämpft in der Sehnsucht nach der Ohnmächtigkeit wurde die Seele, und Bewußtheit, Besonnenheit trat ein.

Dasjenige, was wir heute als individueller Mensch erreichen müssen, wurde dazumal im Zusammenleben mit den anderen Menschen erreicht. Man brauchte sozusagen um sich eine Bevölkerung, die mehr Todeskräfte in sich hatte als eine herrisch auftretende, aber junge, nicht zu voller Besonnenheit kommende Bevölkerung. Die rang sich hinauf zu dem, was sie als Menschen brauchten, dadurch, daß sie eine andere Bevölkerung überwanden. Und so sind diese oftmals so furchtbaren, uns heute so barbarisch anmutenden altorientalischen Kämpfe nichts anderes als die Impulse der Menschheitsentwickelung überhaupt. Sie mußten da sein. Sie sind die Impulse der Menschheitsentwickelung. Die Menschheit hätte auf der Erde sich nicht entwickeln können, wenn nicht diese uns heute barbarisch anmutenden furchtbaren Kämpfe und Kriege vorhanden gewesen wären.

Die Eingeweihten der Mysterien, die sahen dann eben die Welt doch schon so, wie sie heute gesehen wird, nur verbanden sie damit eine andere Seelenverfassung, eine andere Gesinnung. Für sie war dasjenige, was sie in scharfen Konturen erlebten, so wie wir heute beim sinnlichen Wahrnehmen die äußeren Dinge in scharfen Konturen erleben, für sie war das immerhin dasjenige, was von den Göttern kam, auch für das menschliche Bewußtsein von den Göttern kam. Denn wie trat das vor einen damaligen Eingeweihten?

Sehen Sie, da war vielleicht, sagen wir, der Blitz. Nehmen wir ein recht anschauliches Bild. Nun, ihn sieht der heutige Mensch so, wie Sie ja wissen, daß man eben den Blitz sieht (siehe Zeichnung, oben). Das sah der alte Mensch nicht so. Der sah hier lebend-geistige Wesenheiten sich bewegen (gelb), und die scharfen Konturen des Blitzes verschwanden vollständig. Das war ein Heereszug oder eine Prozession von Geistwesen, die über dem oder im Weltenraum vorwärtsdrangen. Den Blitz als solchen sah er nicht. Er sah einen Geisterzug durch den Weltenraum schweben. Für den Eingeweihten wurde das so, daß er ja auch wie die anderen Leute diesen Heereszug sah, aber für sein Schauen, das in ihm entwickelt worden war, konnte sich, indem das Bild von dem Heereszug allmählich sich dämpfte und dann verschwand, der Blitz herausentwickeln in der Gestalt, wie ihn heute jeder sieht. Die ganze Natur, wie sie heute jeder sieht, mußte in alten Zeiten erst durch die Initiation errungen werden. Aber wie empfand man dieses? Auch dieses empfand man durchaus nicht in der Gleichgültigkeit, mit der man heute Erkenntnisse oder Wahrheiten empfindet. Man empfand dieses durchaus mit einem moralischen Einschlag. Und wenn wir uns das anschauen, was mit den Jüngern der Mysterien geschah, so müssen wir uns das Folgende sagen: Sie wurden eingeführt in diejenige Naturanschauung, die dann später die naturgemäße, allen zugängliche war. Einzelne nur wurden durch harte innere Prüfungen und Proben zu dieser Naturanschauung hingeführt. Dann aber hatten sie ganz naturgemäß folgende Empfindung: Da ist der Mensch mit seinem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein. Er sieht diesen Heereszug von Elementarwesen dutch die Lüfte reiten. Aber er ist dadurch, daß er eine solche Anschauung hat, bar des menschlichen freien Willens. Er ist ganz hingegeben an die göttlich-geistige Welt. - Denn in diesem wachenden Träumen, träumenden Wachen lebte der Wille nicht als freier, sondern als derjenige, der in den Menschen einströmte als der göttliche Wille. Und der Eingeweihte, der den Blitz gun herauskommen sah aus diesen Imaginationen, der empfand das so, daß er sagen lernte durch seinen Initiator: Ich muß ein Mensch sein, der in der Welt sich auch bewegen darf ohne die Götter, für den die Götter auswerfen ins Unbestimmte den Welteninhalt. - Es war gewissermaßen für die Initiierten dasjenige, was sie in scharfen Konturen sahen, der von den Göttern ausgeworfene Welteninhalt, an den der Eingeweihte herantrat, um unabhängig zu werden von den Göttern.

Sie begreifen, es wäre ein unerträglicher Zustand gewesen, wenn er nicht irgendein ausgleichendes Moment gehabt hätte. Das hat er aber gehabt. Denn indem der Eingeweihte auf der einen Seite Asien erleben lernte gottverlassen, geistverlassen, lernte er auf der anderen Seite einen noch tieferen Bewußtseinszustand kennen als derjenige war, der zur zweiten Hierarchie hinreichte. Er lernte kennen zu seiner entgötterten Welt die Welt der Seraphim, Cherubim und Throne.

In einer bestimmten Zeit der asiatischen Entwickelung, die etwa die mittlere ist - wir werden über die Zeiten noch genauer zu sprechen haben -, war der Bewußtseinszustand dieser Menschen, dieser Eingeweihten so, daß sie über die Erde hingingen und ungefähr schon den Anblick von den Erdenreichen hatten, den der moderne Mensch hat; aber das fühlten sie eigentlich in ihren Gliedern. Sie fühlten ihre Glieder befreit von den Göttern in der entgötterten Erdenmaterie. Aber dafür begegneten sie in diesem götterlosen Lande den hohen Göttern der Seraphim, Cherubim und Throne. Man lernte als Eingeweihter nicht mehr bloß kennen jene graugrünen Geistwesen, welche die Bilder des Waldes, die Bilder der Bäume waren, sondern man lernte als Eingeweihter kennen den Wald geistlos, aber man hatte dafür das Ausgleichende, daß man in dem Walde gerade den Angehörigen der ersten Hierarchie begegnete, irgendeinem Wesen aus dem Reiche der Seraphim, Cherubim oder Throne.

Das alles als soziale Konfiguration aufgefaßt, ist eben das Wesentliche im geschichtlichen Werden des alten Orients. Und die treibenden Kräfte der Weiterentwickelung, sie sind diejenigen, die den Ausgleich suchen zwischen jungen Rassen und alten Rassen, so daß die jungen Rassen an den alten reif werden können, gerade an den unterworfenen Seelen reif werden können. Und so weit wir nach Asien hinüberblicken, überall finden wir dies, daß junge Rassen, die durch sich selber nicht besonnen werden können, die Besonnenheit im Erobern suchen. Aber wenn wir den Blick von Asien herüberlenken nach Griechenland, dann finden wir, daß da etwas anders wird. In Griechenland drüben war auch schon in den herrlichsten Zeiten der griechischen Entwickelung eine Bevölkerung, welche allerdings das Älterwerden verstanden hat, aber nicht verstanden hat, das Älterwerden zu durchdringen mit voller Geistigkeit. Ich habe ja öfter aufmerksam machen müssen auf jenen charakteristischen Ausspruch des weisen Griechen: Besser ein Bettler sein in der Oberwelt als ein König im Reiche der Schatten. - Mit dem Tode draußen und mit dem Tode auch drinnen im Menschen kam der Grieche nicht zurecht. Aber auf der anderen Seite hatte er diesen Tod wieder in sich. Und so war bei dem Griechen nicht eine Sehnsucht nach Besonnenheit, die als Impuls in ihm vorhanden gewesen wäre, sondern bei dem Griechen war es die Angst vor dem Tode. Diese Angst vor dem Tode empfanden die jungen orientalischen Völker nicht, denn sie zogen auf Eroberungen aus, wenn die Menschen als Rasse den Tod nicht in der richtigen Weise erleben konnten.

Der innere Konflikt aber, den die Griechen mit dem Tode erlebt haben, der führte als ein innerer Menschheitsimpuls zu dem, wovon uns berichtet wird als dem Trojanischen Krieg. Die Griechen brauchten nicht den Tod bei einer fremden Bevölkerung zu suchen, um die Besonnenheit sich zu erobern, die Griechen brauchten aber gerade für dasjenige, was sie vom Tode empfanden, das innere lebensvolle Geheimnis vom Tode. Und das führte zu jenem Konflikte zwischen den Griechen als solchen und den Menschen, von denen die Griechen hergekommen waren in Asien. Der Trojanische Krieg ist ein Sorgenkrieg, der Trojanische Krieg ist ein Angstkrieg. Wir sehen, wie einander gegenüberstehen im Trojanischen Kriege die Repräsentanten der kleinasiatischen Priesterkultur und die Griechen, die den Tod schon in sich fühlen, aber mit dem Tode nichts anzufangen wissen. Die übrige orientalische Bevölkerung, die auf Eroberungen auszog, die wollte den Tod, die hatte ihn nicht; die Griechen hatten den Tod, wußten aber mit ihm nichts anzufangen. Sie brauchten einen ganz anderen Einschlag, um mit dem Tode etwas anfangen zu können. Achill, Agamemnon, alle diese Leute tragen den Tod in sich, wissen aber nichts mit ihm anzufangen. Sie schauen hinüber nach Asien. Und sie haben in Asien drüben eine Bevölkerung, die in der umgekehrten Lage ist, die unter dem unmittelbaren Eindruck der entgegengesetzten Seelenlage leidet. Da drüben sind diejenigen Menschen, die den Tod nicht in dieser intensiven Weise fühlen wie die Griechen, die den Tod fühlen als etwas, was im Grunde doch lebenstrotzend ist.

In einer wunderbaren Weise hat das eigentlich Floszer zum Ausdrucke gebracht. Überall, wo die Trojaner den Griechen gegenübergestellt werden - sehen Sie sich an die charakteristischen Figuren Hektor und Achill -, überall ist dieser Gegensatz da. Und in diesem Gegensatze drückt sich aus, was an der Grenze von Asien und Europa geschieht. Asien hatte in jener alten Zeit sozusagen einen Überschuß des Lebens über den Tod, sehnte sich nach Tod. Europa auf griechischem Boden hatte einen Überschuß von Tod im Menschen, mit dem man nichts anzufangen wußte. So standen sich Europa und Asien von einem zweiten Gesichtspunkte aus gegenüber: auf der einen Seite der Übergang des rhythmischen Erinnerns in das zeitliche Erinnern, auf der anderen Seite das ganz verschiedene Erleben gegenüber dem Tode in der menschlichen Organisation.

Wir werden dann morgen diesen Gegensatz, den ich Ihnen am Schlusse der heutigen Betrachtung nur andeuten konnte, genauer betrachten, um so jene tief in die Menschheitsentwickelung einschneidenden Übergänge kennenzulernen, die von Asien nach Europa herüberführen und ohne deren Verständnis im Grunde genommen doch auch nichts in der gegenwärtigen Entwickelung der Menschheit zu verstehen ist.

Second Lecture

From yesterday's presentations, it will have become clear to you how one can only get a correct view of the historical course of human development on earth by engaging with the very different soul states that were present in the different ages. And yesterday I tried to limit the actual ancient Oriental, the Asian development, tried to point to that period of time in which the descendants of the Atlantic population found their way from the West to the East after the Atlantic catastrophe and gradually populated Europe and Asia. What then happens to these peoples in Asia is entirely under the influence of the state of mind of these people, who were accustomed to the rhythmic. At the beginning we still have the echoes, the distinct echoes of what was fully present in Atlantis: localized memory. Then, during the oriental development, it passes over into rhythmic memory. And I have already shown you how the change to temporal memory first occurs with Greek development.

But this means that the actual Asian development – because what history represents are already states of decadence – is that of people of a completely different nature than those of later times, and the external historical events in those ancient times are much more dependent on what lived in the human mind than they were later. What lived in human minds in those older times lived in the whole human being. People did not have a separate soul and thought life as they do today. They did not have this thinking that no longer feels any connection with the inner processes of the human head. There was no abstract feeling that no longer felt connected to the blood circulation. Instead, there was only thinking that was simultaneously experienced inwardly as an event in the head, a feeling that was experienced in the rhythm of breathing and blood circulation, and so on. The whole person was experienced and felt in undivided unity.

But all this was connected with the fact that one also experienced one's relationship to the world, to the universe, to the cosmos, to the spiritual and physical in the cosmos quite differently than later. Today's human being experiences himself on earth more or less in the countryside or in cities. He is surrounded by what he sees as forests, as rivers, as mountains, or he is surrounded by what is the city's walls. And when he speaks of the cosmic-supernatural, well, where is it actually? The modern human being, so to speak, cannot indicate any sphere in which he should imagine the cosmic-supernatural. It is nowhere actually tangible for him, I mean also not spiritually tangible, comprehensible. That was not so in that old oriental development, but in that old oriental development, the environment that we would call the physical environment today was actually only the lowest part of a unified world. Around man was that which is contained in the three kingdoms of nature, that which is contained in the river and the mountain and so on, but at the same time it was permeated, if I may say so, interwoven with spirit. And man said: I live with mountains, I live with rivers, but I also live with the elemental spirits of the mountains, of the rivers. I live in the physical realm, but this physical realm is the body of a spiritual realm. The spiritual world is all around me, the lowest spiritual world.

There was this realm, which has now become the earthly realm for us, below. Man lived in it. But he imagined (see drawing) that where this realm (light) ends at the top, another one begins (yellow-red), into which the lower one merges, and then another (blue), and finally the highest one that can still be reached (orange). And if we wanted to name these realms according to what has become common among us in anthroposophical knowledge - in the ancient oriental life they had other names, but that does not matter, we want to name them as they are called for us -, then we would have the first hierarchy at the top: Seraphim, Cherubim, Thrones, then the second hierarchy: Kyriotetes, Dynamis, Exusiai, and the third hierarchy: Archai, Archangeloi, Angeloi.

And now came the fourth realm, where human beings live, where today, according to our knowledge, we only place natural objects and natural processes, where these human beings felt that natural processes and natural things were permeated by the elemental spirits of water and earth. And that was Asia (see drawing).

Asia meant the lowest spiritual realm, where man still exists. However, what is our usual view today, which man has for his usual consciousness, was not the case in those ancient oriental times. It would be quite nonsensical to think that in those ancient oriental times one would have had the possibility of suspecting spiritless matter somewhere. What we talk about today, oxygen, nitrogen, would have been pure impossibility for those ancient times. Oxygen was the spiritual, the invigorating, the energizing, that had an accelerating effect on the life of the living. Nitrogen, which we today imagine as being contained in the air mixed with oxygen, was that spiritual substance that permeates the world and, by acting on living organic matter, prepares this organic matter to receive a soul. This was the only way in which oxygen and nitrogen, for example, were known. And so all natural processes were known to be connected with the spiritual, because the view that one has today as a man in the street was not at all had. Some had it, and these were precisely the initiates. For the ordinary everyday things, the other people had a state of consciousness that is very similar to a waking dream, but it is a dream state that we only have in abnormal experiences. Man went about with this dreaming. With this dreaming he approached the meadows, the trees, the rivers, the clouds, and he saw everything in this way, as one can see and hear in this dream state.

Just imagine what can happen there for today's man. Man has fallen asleep. Suddenly, the image of a fiery furnace appears before him in his dream. He hears: Feurio! Outside, the fire brigade is passing by to extinguish a fire somewhere. How different what the human mind perceives in a dry way, as they say, and the ordinary sensory perception of the fire brigade's actions is from what a dream can reflect to a person. But everything that ancient oriental humanity experienced was poured into dreams. Everything outside in the realms of nature was transformed into images. And in these images, people experienced the elemental spirits of water, earth, air and fire. And the kind of deep sleep we have today – I mean the kind of sleep where you just lie there like a sack and are completely unaware of yourself – people in those days did not have that. Isn't it true that this kind of sleep still exists today? But people in those days did not have it; instead, they also had a dull consciousness during this sleep. While they rested their bodies, as we call it today, the spiritual in them wove in an activity of the outer world. And in this weaving one perceived that which is the third hierarchy. Asia was perceived in the ordinary waking dream state, that is, in the everyday consciousness of that time. The third hierarchy was perceived in sleep. And into this sleep then at times plunged a still dull consciousness, but a consciousness that deeply engraved its experiences in the human mind. So there was this everyday consciousness for these oriental people, where everything was transformed into images and pictures. They were not as real as those of the older times, for example the Atlantean or even the Lemurian or the Moon Age, but they were still pictures that were present even during this oriental development.

So these people had these images. Then, in their sleep states, they had what they could clothe in words: when we fall asleep from our ordinary earthly existence, we enter the realm of the Angeloi, Archangeloi, and Archai and live among them. The soul frees itself from the organism and lives among the beings of the higher hierarchies.

At the same time, it was clear that while living in Asia, with gnomes, undines, sylphs, salamanders, that is, with the elemental spirits of earth, water, air, fire, that one experienced the entities of the third hierarchy in the state of sleep in which the body rested, but at the same time experienced with the planetary existence, with that which lives in the planetary system belonging to the earth. But then sometimes a very special state entered into the sleep-consciousness, where the third hierarchy was perceived, in which the sleeper felt: A completely alien realm is approaching me. Something takes me in itself, something takes me away from earthly existence. One did not yet feel this when one was placed in the third hierarchy, but when this deeper state of sleep came, one felt it. Actually, there was never any clear awareness of what happened during this state of sleep of the third kind. But what was experienced from the second hierarchy penetrated deeply, deeply into the whole human being. And when he woke up, he had it in his mind and said: I have been graced by higher spirits who have a life above planetary existence. And so these people then spoke of that hierarchy, which includes the Exusiai, the Kyriotetes and the Dynamis. And what I am telling you now was basically the ordinary consciousness in ancient Asia. From the very beginning, everyone had the two states of consciousness, waking-sleeping, sleeping-waking, and sleep, into which the third hierarchy reached. And some, because of their special nature, had this penetration of a deeper sleep, where the second hierarchy played into human consciousness. And the initiates in the mysteries received a further state of consciousness. Which one? That is precisely what is so surprising. If you give the answer to that, “Which state of consciousness did the initiates of that time receive?”, the answer is: the state of consciousness that you always have during the day today. You develop it naturally in your second or third year of life. The ancient Oriental never came to this naturally, but had to develop it artificially. He had to develop it out of waking dreams and dreaming waking. While he, when he walked around with his waking dreams, dreaming waking, saw images everywhere that more or less symbolically gave only what we see today with sharp contours, the initiates came to see things as people today see them with ordinary consciousness every day. And the initiates came to learn through this newly developed consciousness what every schoolboy and schoolgirl learns in elementary school today. And the difference was not that the content was different. However, the abstract letter forms that we have today did not exist back then. The writing had characters that were more intimately connected to the things and processes of the world. But still, in those ancient times, only the initiated learned to write and read, because you can only learn to write and read in the intellectual state of consciousness that is now the natural one.

If you could imagine that this ancient oriental world would arise again with people of that kind, as they were then, and you would enter among these people with your soul-dwelling of today, you would be an initiate for those people back then. The difference is not in the content. You would be an initiate, but you would be driven out of the country by the people of that time by every means possible the moment you were recognized as an initiate, because people would be aware that as an initiate you are not allowed to know things the way people today know them. One may not, for example, write as people of the present time write, according to the view of the people of that time, the view of that time. If I put myself in the mind of that time and such a pseudo-initiate, that is, an ordinary person, an ordinary clever person of the present day, were to approach me, this person of that time would say: He can write, he puts signs on paper that mean something, and he is not even aware of how infinitely devilish it is to do something like that and not to carry within himself the awareness that one may only do so on behalf of the divine world consciousness, that one may only put signs that mean something on paper if one is aware: the God works in the hands, in the fingers, the God works in the soul, so that the soul expresses itself through these letter-forms. This, which does not lie in the diversity of the content, which lies in the human conception of the matter, is what the initiates of ancient times still had quite differently from today's people, who have the same content. If you read my book, “Christianity as a Mystical Fact”, which has now been reprinted, you will find it indicated right at the beginning that this is actually where the essence of the initiate of ancient times lay. And it is actually always so in the evolution of the world: What arises naturally in man in a later time can be attained in an earlier time through initiation. Precisely by presenting something like this, you will feel the fundamental difference between the state of mind of these ancient oriental peoples of prehistoric development and that of people who entered civilization later. It is a different humanity that called the lowest heaven Asia and understood their own country to be the nature that surrounded them. They knew where the last heaven was. Compare this with today's views, how little people of the present consider what surrounds them to be the last heaven. Most of them cannot consider it to be the last because they do not know the previous ones either. Now, we see that the spiritual extends far into the natural existence in this ancient time. And yet, we encounter something among these people that may seem infinitely barbaric to us in the present time, at least to many of us. It would have seemed terribly barbaric to people in those days if someone had been able to write with such an attitude as one can write with today. It would have seemed devilish to them. But to a large number of people in the present day, it certainly seems barbaric, as in that part of Asia it was taken for granted that a people migrating from west to east would often subject another people, who were already settled, with great cruelty, conquering their land and making the population into slaves. This is the content of this oriental history over the whole of Asia. While these people had a high spiritual view in the way I have just characterized it, the outer history was one of continuous conquests of foreign lands, whose population was subjugated. This certainly appears barbaric to many people in the present day. And even if wars of conquest still somehow exist today, even those who defend them do not have a completely clear conscience about them. You can tell from the defenses of the wars of conquest: they do not have a completely clear conscience about them. In those days, on the other hand, they had the very best of consciences regarding wars of conquest, and they thought that conquest was God-given. And what later spread over a large part of Asia as a yearning for peace is actually a late product of civilization. On the other hand, the early product of civilization for Asia is the continuous conquest of countries and the subjugation of their populations. The further back one looks into prehistoric times, the more one finds this conquest, of which only a shadow remains of what Xerxes and similar people did.

But this principle of conquest is based on something very specific. In those days, due to the states of consciousness I have described to you, man was in a completely different situation in relation to other people and to the world than he is today. Certain differences in the population of the earth have lost their fundamental significance today. At that time, they existed in a completely different way than they do today. And so let us put something that was often real before our minds as an example.

Let us assume that on the left we have the European area (see illustration on page 36) and on the right the Asian area. A conquering population (red) could come from the north of Asia, expand over some area in Asia, and subjugate the population (red around yellow).

What actually lay ahead? In the cases characterized, in which the actual historical development was in flux, the population that emerged as conquerors was always young as a people or as a race – young, full of youthful strength. Now, what does it mean to be young among people in the present development of the earth? For people in the present stage of evolution on earth, being young means carrying so much of the forces of death within themselves at every moment of their lives that they can supply the soul forces needed for the dying processes of the human being. We do, of course, have the sprouting, sprouting life forces within us; but these do not make us level-headed, they make us powerless, unconscious. The degenerative, the death forces, which are also constantly at work in us, are only ever overcome by the life forces during sleep, so that we only combine all the death forces in the unique death at the end of life, these death forces must be constantly within us. They bring about composure, consciousness. But this is precisely a characteristic of present-day humanity. Such a young race, a young people, suffered from its overly strong life forces. What was human there constantly felt: I am constantly pressing my blood against my body walls. I cannot stand it. My consciousness does not want to become aware. I cannot develop my full humanity because of my youth.

Of course, ordinary people did not speak in this way, but it was the language of the initiates of the mysteries, who were still guiding and directing all these historical events at the time. And so such a population had too much youth, too much life force, and too little of what could give composure. Then it went out and conquered a region where an older population lived that had already absorbed forces of death in some way because it had already fallen into decadence. It did not need to enter into a blood relationship between the conquerors and those made slaves. What unconsciously took place in the souls of the conquerors and the enslaved people had a rejuvenating effect, and it worked towards composure. And the conquering man, who had established his court where he now had his slaves, also only needed the influence on his consciousness. He only had to turn his mind to these slaves, and, I would say, the soul was subdued in its longing for powerlessness, and awareness, reflection, entered.

What we have to achieve today as individuals was achieved in the past through living together with others. They needed, so to speak, a population that had more death forces in itself than a young, imperious population that had not yet fully come to its senses. They struggled to achieve what they needed as human beings by overcoming another population. And so these often so terrible ancient oriental struggles, which today seem so barbaric to us, are nothing other than the impulses of the development of humanity in general. They had to be there. They are the impulses of the development of humanity. Humanity would not have been able to develop on earth if these terrible struggles and wars, which today seem barbaric to us, had not existed.

The initiates of the mysteries then saw the world as it is seen today, but they associated it with a different state of mind, a different attitude. For them, what they experienced in sharp contours, just as we today experience external things in sharp contours through our senses, was, after all, that which came from the gods, and for human consciousness came from the gods. For how did this appear to an initiate of that time?