The Stimulating Effect of Anthroposophy on the Individual Sciences

GA 76

5 April 1921, Dornach

Translated by Steiner Online Library

3. Mathematics and the Inorganic Natural Sciences

If I attempt today to make the transition from the actual philosophical field to the field of the specialized sciences, then in our present epoch this transition is to be accomplished quite naturally through a consideration of the mathematical and physical, chemical, that is, the inorganic natural world , because by far the majority of present-day philosophical conceptions are constructed in such a way that philosophers base them on concepts and ideas gained from the field of science that is considered the most secure today, namely from mathematics and inorganic natural science.

If we wish to discuss the mathematical treatment of inorganic natural science, which is so popular today, we must always remember something that has already been mentioned in the opening speech: the connection that current thinking believes it can make with Kant, precisely with the introduction of mathematics into inorganic natural science, indeed into science in general.

What must be emphasized in this and also in a later context from the negative side, I say expressly from the negative side, has already been noticed by individual thinkers who are very far removed from the use of supersensible knowledge. Thus, the negative, that is, the rejection of the purely mathematical treatment of natural science, can be found, for example, in a thinker like Fritz Mauthner, who, out of a certain acumen in a negative sense, that is, in rejecting what appears as false claims of a false science, is not at all unhappy. And with regard to the question: What can current science not do? – we can learn a lot from a thinker like Fritz Mauthner, learning through the negative that he presents, and learning through the fact that he does not want to stop at this negative, but would like to advance to a positive realization.

Why shouldn't you also learn from such a negative thinker? If I was able to quote Ludwig Haller as saying yesterday that, in his opinion, Kant took the weapons from the arsenal of light to use them in the service of darkness, why should you not also borrow the weapons from the arsenal of darkness, even the deliberate darkness of knowledge as found in Fritz Mauthner, to use them in the service of light?

Attention is to be paid, as I said, to Kant's saying that there is only as much actual science in each individual discipline as there is mathematics in it.

If you study the history of the use of this Kantian saying up to the present day, you get an interesting example to answer the question of how to be a Kantian at all in modern times. For the people who refer to this saying believe that as much real science as there is mathematics in it is brought into every single science. But Kant means something quite different. Kant means: as much as he brings mathematics into science, that much is mathematics, that is, real science, and the rest is not science at all in the individual sciences.

You see, you become a Kantian if you thoroughly misunderstand a Kantian saying. For the Kantian approach in this area has something like the following logic: if I say, in a gathering in which there are a thousand people, there is as much genius in it as three ingenious people have contributed, I certainly do not mean that the thousand people have now been given the genius of the three people. Nor does Kant mean that the rest of science has acquired the scientific character of mathematics; rather, he means that only the small part that has remained mathematics even in the sciences is real science, but the rest is not science at all.

We must study such things seriously – and in an empirical age we must do so empirically, not a priori – so that such questions are not answered as they often are today, but so that we may come upon the truth.

Now, however, one can point out something else: the most outstanding mathematical thinkers of modern times define mathematics something like this: it would be the “science of sizes”. Well, today it is the science of sizes. But go back just a few centuries to the time when Cartesius and Spinoza found great satisfaction in presenting their philosophy “according to a mathematical method,” as they say, and you will find that what Cartesius and Spinoza wanted to bring into their philosophy as a mathematical method is quite different from what is to be brought into natural science as mathematics in more recent times.

If we go back to Descartes and Spinoza, we find that these two philosophers want to construct their philosophical system in such a way that there is just as much certainty in the transition from one proposition to another as there is in mathematics. That is to say, they want to build their philosophy according to the pattern of these mathematical methods; but not by introducing into their philosophy what is understood by mathematics today. So, by going back to Descartes and Spinoza, we have already associated a completely different meaning with the word mathematics. If we disregard the aspect that merely refers to quantities, we have associated the sense of the inner, secure transition from judgment to judgment, from conclusion to conclusion. We have considered the nature of mathematical thinking, not what we can call a science of quantities.

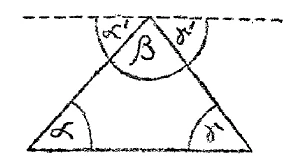

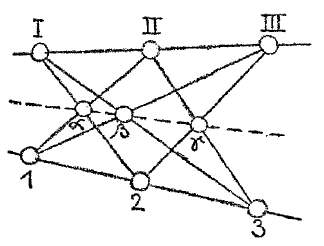

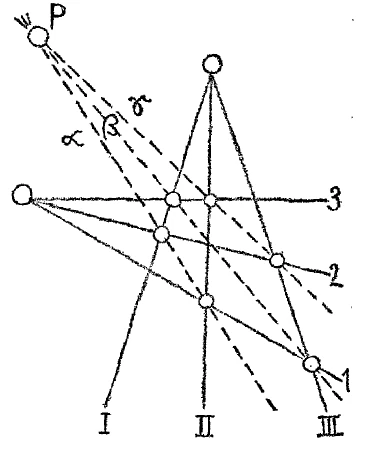

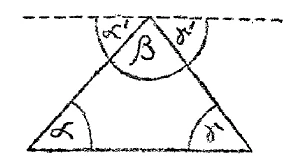

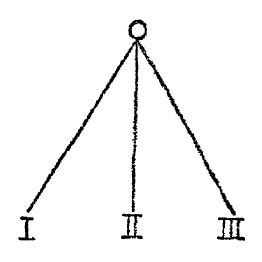

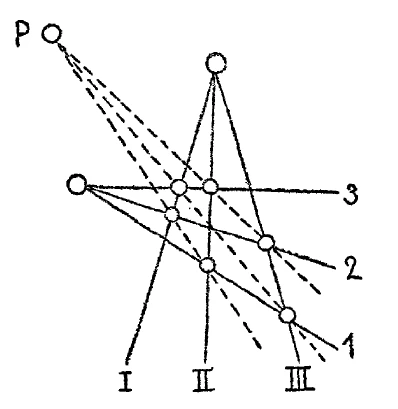

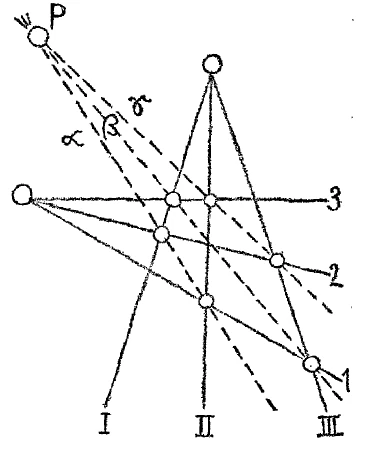

And let us go back even further. In ancient times, the word “mathematics” had a completely different meaning altogether. Then it was identical with the word science. This means that when one meant 'science', one spoke of 'mathesis' or 'mathematics', because in mathematization one found the certainty of an inner insight into a 'fact' present in consciousness. One associated the sense of 'knowledge' and 'science' with this word. And so a much more general concept has been transferred to the narrow field of the theory of quantities. Today we have every reason to remember such things, because we are faced with the necessity of looking again at what actually lies at the basis of mathematical thinking. What is the essential feature of mathematical thinking? The essential feature of mathematical thinking is precisely the transparency of the mathematical content of consciousness. If I draw a triangle and consider its three angles, alpha, beta, and gamma, and want to prove that the sum of these three angles is 180 degrees, then I do the following (see figure r): I draw a parallel to the base line through the uppermost point of the triangle, look at the ratio of the angles alpha and gamma to the alternate angles that arise at the parallel, and then, by observing how the three angles that arise at the parallel – gamma', alpha', and beta – are positioned in relation to one another and how they form an angle of 180 degrees, I have the proof that the three angles of the triangle are also 180 degrees. That is to say, what is present in the mathematical as a conscious fact right up to the lines of reasoning is manageable and accompanied by inner experience from beginning to end. And this is the basis of the certainty one feels in mathematical thinking: that everything that is present as a conscious fact is accompanied by inner experience right up to the judgment and the proof.

And when we then look at the external world, whose material foundations cannot be penetrated with such clarity, we still feel satisfied when observing external nature if we can at least follow its phenomena in the experience that first met us in clarity.

The certainty that one feels in this clarity of consciousness in mathematics becomes particularly apparent when one looks at what is universally recognized as a major advance in mathematics in the 19th century century: what emerged as “non-Euclidean geometry”, as “metageometry” in Lobatschewskij, Bolyai, Legendre and so on.

There we see how, based on the inner certainty of intuition, the Euclidean axioms are first modified and, by modifying the Euclidean axioms, possible other geometries than the Euclidean one are constructed, and how one then tries to cope with an inscrutable reality using what has been constructed as an extension of intuitiveness. All the ideas that have entered modern thought through this “meta-geometry” are basically factual proof of the certainty that one feels in the comprehensibility of mathematization.

And with regard to Euclidean space – for the spaces of the other geometries are simply other spaces – which is characterized by the fact that three coordinate axes perpendicular to one another have to be imagined , that what has been presented here as proof of the 180-degree nature of the three angles of a triangle applies to this Euclidean space. And everyone will realize that if the Euclidean axioms are modified, this may have a bearing on our space, in which we are – which is then precisely not Euclidean space, but perhaps an internally curved space – but that for Euclidean space, which can be comprehended, the Euclidean results must be assumed to be certain because of their comprehensibility. No one will doubt that.

And just when you see through these facts, then you will find: the application of mathematics to the field of natural science is based on the fact that one finds in the external world that which is first found internally, that, so to speak, the facts of the external world behave in such a way as corresponds to the mathematical results that we first found independently of this external world in inner contemplation.

But one thing is absolutely certain: I would say, the precondition for this inner vision of the mathematical is that this mathematical first appears to us as an image. The inner free activity of constructing, which we experience in mathematizing, is such an inner free activity only because nothing of what otherwise prevails within our human beingness, when, for example, we want or the like, following an instinct. From this, what arises as a stock of consciousness in the process of mathematization is, as it were, elevated to the point of becoming pictorial. In relation to what is “external natural reality”, the mathematical is unreality. And we feel the satisfaction in the application of the mathematical to the knowledge of nature precisely because we can recognize what we have freely grasped in pictorial form in the realm of being.

But precisely for this reason it must be admitted that on the one hand it is justified when such minds, which do not merely want to go to what natural reality as such shows in human observation as real, but want to go to the full, total reality, like Goethe, when such spirits — as Goethe particularly showed in his treatment of the “Theory of Colors” — do not want a total application of the mathematical to all of external reality. Goethe's rejection of mathematics arose precisely from the realization that, although what corresponds to the pictorial vividness of the mathematical can be found in external nature through mathematics, at the same time one thereby renounces everything qualitative. Goethe did not want to treat only the quantitative in external nature; he also wanted to include the qualitative.

On the other hand, however, it must be said that the whole inner greatness of mathematics is based on its pictorial nature, and that it is precisely in this pictorial nature that we must seek what gives it the character of an a priori science, a science that can be found purely through inner contemplation.

But at the same time, by mathematizing, one is actually outside of nature, in contrast to which mathematics is of particular interest. Nowhere does one grasp something that is effective in itself, but only the relationships of this effectiveness that can be expressed by mathematical formulas. When you calculate a future lunar eclipse in mathematical formulas, or, by inserting the corresponding variables in negative form, a lunar eclipse that has passed in the past, you must be aware that you never penetrate into the inner essence of what is happening, but only grasp the quantum of relationships with mathematical formulas from a certain point of view. That is to say, one must realize that one can never penetrate into the inner essential differentiation through mathematics if one understands mathematics in the narrow sense in which it is still often understood today.

But even within mathematics we can already see a kind of path that leads out of mathematics itself. From what I have just said, you can see that this path, which leads out of the mathematical, should be similar to the path we take when we submerge into nature, which has been thoroughly penetrated and is penetrating, with the purely pictorially mathematical, with the unpenetrated, ineffectively pictorially mathematical. There we submerge into something that, in a sense, intercepts us with our free mathematizing activity and constricts mathematical formulas into an event that is effective in itself, that is in itself something to which we have to say: we cannot fully grasp it with mathematics; in the face of the inner transparency of mathematics, this thing asserts its essential independence and its essential interiority.

This path, which is taken when one simply seeks the transition from the unreal mathematical way of thinking to the real scientific way of thinking, can in a certain way already be found today within the mathematical itself in a certain relation. And we see how it can be found if we look not outwardly but inwardly at the attempts that thinking has made in the transition from mere analytical geometry to projective or synthetic geometry, as presented by more recent science. I would like to explain what I mean by the sentence I have just uttered using a very elementary, an extremely elementary and well-known example of synthetic geometry.

When you do synthetic, newer projective geometry, you differ from the analytical geometer in that the analytical geometer works with mathematical formulas, that is, he calculates, counts, and so on. The synthetic geometer uses only the straightedge and the compass, and that which can arise in consciousness through the straightedge and the compass as a fact, which first emerges from intuition. But let us ask ourselves whether it also remains purely within intuition.

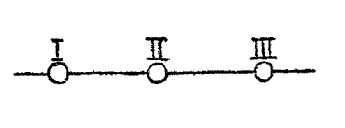

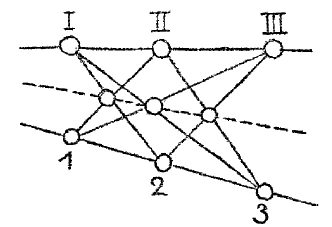

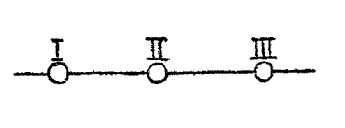

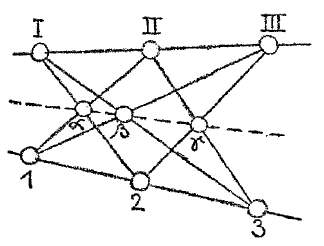

Let us imagine a line – what is called a line in ordinary geometry – and on this line three points. Then we have the following mathematical structure (see Figure 2): a line on which the three points I, II, III are located.

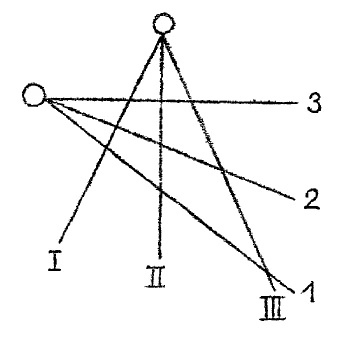

Now, there is – I can, of course, only hint at what I have to present here in the main lines, so to speak appealing to what you already know about the matter – there is another figure which, in a certain way, in its entire configuration, corresponds to the mathematical figure just drawn. And this other figure is created by treating three lines in a similar way to the way I have treated these three points here, and by treating a point in a similar way to the way I have treated the line here. So imagine that instead of the three points ], II, III, I draw three lines on the board, and instead of the line that goes through the three points, I draw a point (see Figure 3); and to create a correspondence, I take the point where the three lines intersect: I have drawn another figure here (Fig. 3). The point that I have drawn above with a small ringlet corresponds to the line on the left, the three, as they are called, rays that intersect at one point, and which I denote by I, II, III, correspond to the three points I, II, III, that lie on the line on the left (Fig. 2).

If you want to feel the full weight of this ruling, you have to take the exact wording as I have just pronounced it. You have to say: the point on the right (Figure 3), which I have marked with a small ring above, corresponds to the line on the left (Figure 2) on which the three points lie; and the rays I, II, III on the right correspond to the points I, II, III on the left. And in that the three rays I, II, III on the right intersect at the one point above, this intersection corresponds to the position of the three points I, II, III on the left on the straight line drawn on the left.

Thus stated, there is a very specific cognitive fact and a corresponding structure on the left opposite the structure on the right.

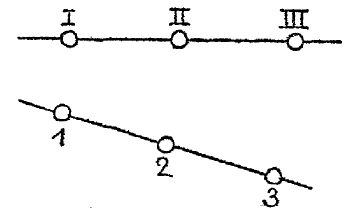

One can now – by remaining purely within the realm of the visual, that is, what can be constructed with compass and straightedge, without the need for calculation – proceed to the following state of consciousness: I draw a line again on the left, and again three points on this line (the lower line in Figure 4).

I have now – I ask you to please consider the way I express myself, which I will follow, as decisive for the facts – I have now drawn the line on the left, on which the three points i, 2, 3 are located. I will proceed and assume – please note the word I pronounce: “and assume” – I will proceed and then assume the following. I will connect the points to the left of one line with the points on the other line in a certain way and will thus obtain connecting lines that will intersect (see Figure 5). I will connect the point I with the point 3, the point III with the point i, the point I with the point 2, the point II with the point 1, the point III with the point 2, the point II with the point 3, and will get intersection points by these lines, which I can then again - I now assume - connect by a straight line. So my construction is carried out in such a clear and transparent way that I can actually do what I have just described. You can actually carry out this construction as follows (dotted line in Figure 5): You see, I have the three points of intersection, which I got in the way I described earlier, so that I can draw the dashed-dotted straight line through them.

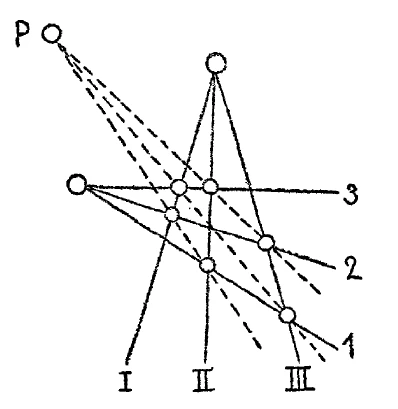

I now assume that by adding another to the right-hand bundle of rays (Figure 3), as it is called, I have the same ratio in the ratio of the radiation as in the distance of the points lying on the left straight line. I shall therefore draw a second bundle of rays on the right (Figure 6), which, in relation to its radiating conditions, corresponds to the positional conditions of the points on the lines on the left. So I have drawn in another bundle of rays here (Figure 6) and call it I, 2, 3, assuming that i, 2, 3 corresponds to i, 2, 3 in relation to the points on the left.

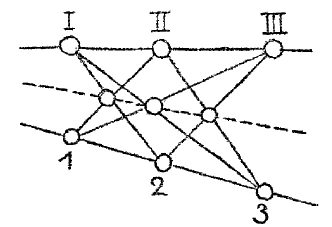

And now I will perform the corresponding procedure on my two ray structures on the right, which I performed on my line and point structures on the left (Figure 5), only I have to take into account that a line on the left corresponds to a point on the right: while on the left I looked for a line connecting two points, on the right I have to look for a point that arises when two rays intersect. The intersection on the right should correspond to the connection on the left (the points of intersection in Figure 6 are marked by small circles, see Figure 7). You can see what I have done: if I connected III with i and 3 with I as points on the left, I brought I with 3 and i with III as lines to the intersection here on the right.

And if I have drawn two lines from the points on the left and brought them to the intersection at one point, I will now draw a line through the two points that I have obtained on the right (dotted line in Figure 7), and I will now carry out the same procedure with respect to the other rays. That is [the lecturer once again illustrates the correspondence between the circled intersections of Figure 7 and the connecting lines of Figure 5], I will bring II into intersection with i, I with 2, III with 2, II with 3; I will therefore look for the points of intersection on the right as I looked for the connecting lines on the left; and, as you see, I have sought these points of intersection on the right by bringing the rays to the intersection in order to draw lines through these points of intersection (dashed lines in Figure 7), just as I sought lines on the left by connecting the points in order to obtain the points of intersection of these intersecting lines (dotted lines in Figure 5).

The connecting lines – but the points of intersection that I obtained on the right – also intersect at a point indicated here by a small ring at the top (P in Figure 7), just as the three points that I obtained on the left lie on a straight line (dashed in Figure 5). That is to say, in the figure on the right, where lines are used instead of points and the connecting lines are intersections, I get a point where the three lines intersect, just as I got a line that passes through the three points on the left. I get a point for the line on the left.

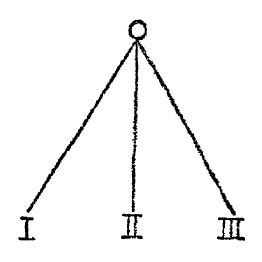

Here I remain, proceeding purely from the realm of the intuitive, although within that which proceeds from intuition but which nevertheless leads to something else. And I ask you to consider the following. Suppose you look in the line, in the direction indicated by the (dashed) line on the left, which goes through the three points of intersection – Alpha, Beta, Gamma. Then you will look up at an intersection point that obscures the others, in relation to which the others are behind it (Figure 8). Here, in the line, you have not only “three points.” But as soon as you move on to a relationship of reality, something quite vivid occurs in relation to these three points: the point gamma is the one in front, and behind it are the points beta and alpha. You have clearly laid this out in the left-hand figure in the illustration.

If we now go through a completely legitimate procedure, which I have described, to the corresponding structure on the right, we have to consider a point instead of a line (P in Figure 9). When we consider this point, we must say that just as on the left an intersection point gamma arises from the connection of III with 2 and the connection of 3 with II, covering the other intersection points, so on the right the necessity arises to introduce what follows and thus, through the law of connection, to pass from the concrete to the non-concrete: On the right (Figure 9), the necessity arises to imagine the curled point (P) in such a way that the ray (Gamma), which is formed by connecting the points of intersection of the lines III and 2, II and 3, first intersects at the curled point with the ray (Beta) that is formed by the preceding ratio ( III with 1, I with 3); and we must imagine that within this curled point the intersections that arise through the three dashed lines also lie as three internally differentiated entities, just as on the left on the dash-dotted line the three points gamma, beta, alpha. That is, I must find the intersections arranged in the individual point on the right so that they coincide one above the other.

That means, in other words, nothing less than: Just as I have to think of the dashed-and-dotted line on the left in such a way that a front and back arises for the points gamma, beta, and alpha for an observing eye, so I have to think of a differentiation within the point, that is, a spatial expansion of zero, in all three dimensions. Seen from the way it has arisen out of this structure, I have to think of this point, not as something undifferentiated, but as having a front and a back. Here I am confronted with the necessity of not thinking of a point as neutral in all directions, but of thinking of the point as having a front and a back.

I am making a journey here, through which I am forced out of the free formation of the mathematical and into something where the objective passes over into an inner determination, into an inner being. You see, this journey is similar to the one through which I pass from the mathematically free formation to the acceptance of this formation from the inner determination within the natural order. And by passing from analytical to synthetic geometry, I get the beginning of the path that is shown to me from mathematics to inorganic natural science.

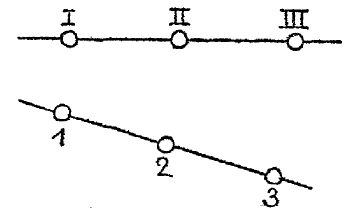

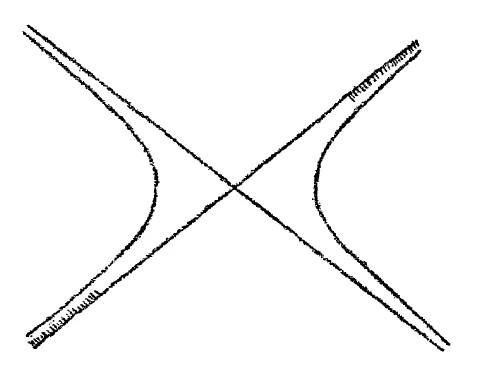

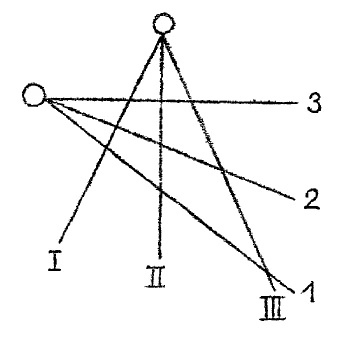

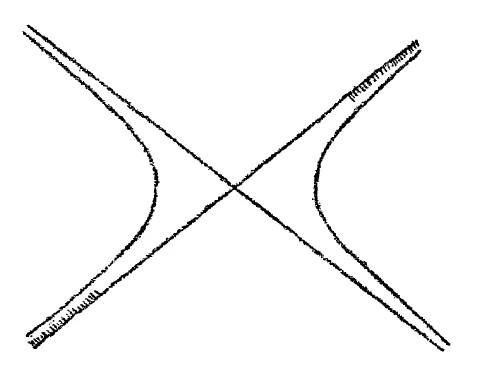

Then, basically, it is only a small step to something else. By continuing these considerations, to which I have now pointed, one can also come to an inner understanding of the following state of consciousness: if one pursues purely with the help of projective, synthetic geometry how a hyperbola relates to an asymptote, then one finds purely intuitively that on the one hand, say at the upper right, the asymptote ptote approaches the hyperbola but never reaches it, but you still get the idea that the hyperbola comes back from the lower left with the other branch, and the asymptote also comes back from the lower left with its other side. In other words, through this relationship between asymptote and hyperbola I get something that I could draw on the board for you in something like the following (Figure 10): at the top right, the asymptote, the straight line, approaches the hyperbola ever closer. I have added a shading there to express what kind of relationship the asymptote actually has to the hyperbola. It is getting closer and closer to him, it wants to get to him, it is getting closer and closer to the essence of its relationship to him. If you now follow this relationship upwards to the right, you will finally come to the conclusion, through purely projective thinking – I can only hint at this here – that the direction of the line that you have upwards to the right, be it the hyperbola or the asymptote, coming from the lower left, , coming from the lower left, the hyperbolast and the asymptote, and this in such a way that it leaves the hyperbolast more and more with its being in the hatched suggestion.

<

So that we can say: this asymptote has a remarkable property. As it ascends to the right, it turns towards the hyperbola with its relationship to the hyperbola; as it comes up again from the bottom left, it turns away from the hyperbola with its relationship to the hyperbola. This line, the asymptote, when I look at it in its entirety, in its totality, has a front and a back again. That is why I was able to draw the shading on one side one time and on the other side the next. I come again into an inner differentiation of the linear, as I come into an inner differentiation when I force the purely mathematical pictorial into the realm of natural occurrence. That is, I approach what occurs as differentiation in the natural occurrence when I want to grasp the mathematical structures themselves in the right way with the help of projective geometry.

What happens through projective geometry can never be done in the same way through mere analytic geometry. For mere analytic geometry, by constructing in coordinates and then searching for the end points of the abscissas and ordinates in its computational form, remains, in its form, completely outside the curve or outside the structure itself. Projective geometry does not stop at the curve and the figure, but penetrates into the inner differentiation of the figure: to the point where one must distinguish between front and back – to the straight line where one must also distinguish between front and back. I have only indicated these properties because of the limited time available. I could also mention other properties, for example, a certain curvature ratio that the point extended in the three spatial dimensions has within itself, and so on.

If you really follow the path from analytical geometry into synthetic geometry with an open mind, if you see how you are, I would say, caught up in something that already approaches reality is already approaching reality, how this reality is present in the external nature, then one has the same inner experience, exactly the same inner experience that one has when one ascends from the ordinary concept of the mind, from ordinary logic, to the imaginative. One must only continue in imaginative cognition. But one has given the beginning when one begins to move from analytical geometry to synthetic. One notices there the interception of what arises from the determination by external reality, after which one has grasped the result, and one notices the same in imaginative cognition.

And now, what is the opposite path within spiritual science to that which leads from ordinary objective knowledge to imaginative knowledge? It would be the one that led from intuition down to inspired knowledge. But there we already find that we are standing inside the real. For with intuition we stand inside the real. And we move away from the real. Descending from intuition to inspiration, we again move away from the real. And when we come down to imagination, we have only the image of the real within.

This path is at the same time the one that the real undergoes in order to become our object of knowledge. Of course, in intuition we are immersed in reality. We move away from reality to inspiration, to imagination, and arrive at our objective knowledge. We then have this in our present knowledge. We make the path from reality to our knowledge. In a sense, we first stand within reality and depart from this reality to arrive at unreal knowledge. On the path we take from analytical geometry into projective or synthetic geometry, we try to move in the opposite direction again, from purely intellectual analytical geometry to where we can begin to think in real terms if we want to achieve anything at all. We are approaching the re-realization of nature, which it undergoes by wanting to become knowledge, by realizing unreal knowledge.

You see, there is no need to assume that our modern spiritual science, as it appears here, wanted to do mathematics differently than mathematicians do when they do mathematics in their own way. There is no need to do much else in the fields that a quantitative natural science has already entered today, except to look for special experimental setups that lead from the quantitative into the qualitative. And when this external quantitative natural science today presents modern anthroposophy with its 'sound results', it is a bit like when someone reads a poem that touches on completely different regions, and someone says: Yes, I cannot decide through my state of mind whether one can live in a poem, but I know something for sure: that two times two is four! No one doubts that two times two is four; nor does anyone doubt what modern inorganic natural science provides who wants to advance to spiritual science. But there is no particular objection to the content of a poem, for example, if you hold up two times two is four to it.

What is at issue, however, is that the individual sciences should seriously and courageously take the path towards a true knowledge of reality that Anthroposophy offers, towards which they are already particularly tending, towards which they want to go. And while some people today, in fruitless scepticism, want to create darkness over what they, often rightly, perceive as the limits of knowledge of nature, anthroposophy wants to start to ignite the light of spiritual knowledge where natural science becomes dark.

And so it will perhaps not make much of a departure from the methods of the sciences mentioned today; but it will present the significance, the inner value of the sciences that have been spoken of today to humanity and will thereby ensure that people know why they penetrate into existence with mathematics, not just why they arrive at a certain certainty with mathematics. For in the end it is not a matter of developing mere products of certainty. We could close ourselves in the narrowest circle and go round and round in the narrowest circle if we only wanted to hold on to “the most certain”. Rather, it is a matter of expanding knowledge. But this cannot be found if one shies away from the path out of inner experience into the outer, into being differentiated in itself. This path is even hinted at in many ways in present-day mathematics and mathematical science. One must only recognize it and then act scientifically in the sense of this knowledge.

Closing Remarks on the Disputation

Dear attendees! Partly because of the late hour and partly for other reasons, I will not say much more than a few remarks related to what has been presented and discussed this evening.

I would like to return very briefly to the question regarding Professor Rein for the reason that one circumstance in this matter should be emphasized sharply.

I am well aware that not much of approval can be said about my “Philosophy of Freedom” by a Herbartian, especially one who has gone through the historical school. This was evident almost immediately after the publication of The Philosophy of Freedom in 1894. One of the first reviews that appeared was by the Herbartian Robert Zimmermann. But I must say that, despite the fact that this review was extremely critical, I was pleased with it because some really great points of view were put forward in opposition at the time. As to how necessary the relationship must be between a Herbartian evaluation and what my Philosophy of Freedom contains, I have not the slightest doubt. But it is a pity that I do not have Professor Rein's review of The Philosophy of Freedom here and could quote the passage as I would like to. It has just been brought to me, and I can therefore say some things even more precisely than would otherwise be possible on the basis of the review. So let me quote from this review, which begins with the words: “In times of such a low level of morality as the German people have probably never experienced, it is doubly important to defend the great landmarks of morality, as established by Kant and Herbart, and not to allow them to be shifted in favor of relativistic tendencies. The words of Baron von Stein, that a nation can only remain strong through the virtues by which it has become great, must be considered one of the most important tasks in the midst of the dissolution of all moral concepts.

The fact that a writing by the leader of the anthroposophists in Germany, Dr. R. Steiner, is involved in this dissolution must be particularly regretted, since one cannot deny the idealistic basic feature of this movement, which aims at a strong internalization of the individual human being, and in its plan of the threefold structure of the social body can find healthy thoughts that promote the welfare of the people. But in his book “The Philosophy of Freedom” (Berlin 1918), he takes his individualistic approach to such an extreme that it leads to the dissolution of the social community and must therefore be fought.

You can clearly see here that the “Philosophy of Freedom” is said to have emerged from the dissolution of all moral concepts and so on – and one can believe that, that it can be the opinion of one man.

Now, a large part of those present here know my views on scientific accuracy, on scientific conscientiousness, and above all, that one should first properly educate oneself about what one writes. To associate the Philosophy of Freedom, which appeared in 1894, even stylistically, with what is implied in the first sentences, is a frivolity. And such frivolity cannot be excused by the fact that the author, who works as a professor of pedagogy at a university, has by no means — as I believe has been said — “gone beyond the bounds of truly objective judgment.” The point is that we can only bring about a recovery of precisely those conditions, which have been discussed here this evening in a rather hearty way, if we do not make ourselves guilty of the same carelessness, but if we strictly exercise scientific conscientiousness precisely towards those who, by virtue of their office, have the task of educating young people. We must not allow those who have this profession to overlook the circumstances and times in which a work was written that they want to judge. That is the first thing I have to say.

Then there is the way of quoting. In this article you will find an incredible way of tearing sentences out of context and then not taking up what is said in my “Philosophy of Freedom”, but rather what the author of the article thinks he is entitled to take up, based on his own opinion, and what can be inferred from his interpretation of the sentences he has quoted.

Anyone who takes the trouble to really read The Philosophy of Freedom will see that it deals in a completely clear way with how to avoid the misunderstandings that Professor Rein criticizes when sentences are taken out of context in any way.

His description of how the Philosophy of Freedom is taken out of its historical context is matched by his placing it in impossible contexts: “If we listen to Dr. Steiner speak, we might be tempted to see him as an apostle of ethical libertinism. He also felt this and countered the objection, which goes: If every person only strives to live out and do as he pleases, then there is no difference between good action and crime. Every crookedness that lies in me has the same claim to be realized as the intention to serve the general good. Dr. Steiner seeks to refute this objection by pointing out that man may only claim the freedom demanded if he has acquired the ability to rise to the intuitive idea content of the world. To acquire this ability is the task of the anthroposophist, who is to rise to the standpoint of ethical individualism.

Now, please ask yourself whether someone is allowed to write such sentences as an assessment of Philosophy of Freedom. Philosophy of Freedom was published in 1894, before the term anthroposophist was coined. Professor Rein also places the “Philosophy of Freedom” in a milieu that was an impossible one for the “Philosophy of Freedom” at the time of its publication, apart from the trivialities that come later, where he speaks of it as an ethics for anthroposophists and angels and the like, and so on.

It is not at all my intention to cast a slur on what I might call the opposing point of view, but to show that this way of judging spiritual matters is part and parcel of the whole world of the person who has to leave our culture behind if the conditions that should be discussed here today are to improve. I may well say that I have carefully considered whether or not I should finally speak these words here. But it seems to me that the matter is important enough, and I believe that I have not crossed the boundary of objectivity, that I have actually confined myself essentially to characterizing the way of judging and not the “point of view” before you here. I know that it is always somewhat precarious to discuss family matters. However, I cannot change my approach, although I am not bound by it anyway, as I have no father-in-law among my colleagues!

Now I would like to make a few other comments, taking up a sentence that has also been discussed here today. Just to speak symptomatically, I would like to relate a small experience, but only to illustrate.

It has been said that it is true that not all students who come to a university or college are ready for that college; but the professors at the colleges cannot be held responsible for that, and these students are simply sent to them by the secondary schools. Yes, but I really could not help but think of a conversation that had once been held in my presence with one of the most famous literary historians at German universities. This literary historian was also on the examination board for grammar school teaching. – I don't really like to do it, but today times are so serious that one must also bring up such things. – He said: Yes, with these grammar school teachers, we know them, we have to examine them, but we sometimes have very strange thoughts when we have to let these camels out as grammar school teachers!

Well, as I said, it is just an illustration that I would like to give through this experience. I don't know if it speaks very strongly for the university teachers when an examiner and famous university teacher deigns to call the teachers of youth who are sent to the grammar schools “camels”. I'm not saying it, but the man in question did say it. I am only quoting. Well, every thought must be thought through to the end. And I believe that when the thought is thought through to the end, university teachers should not complain when incompetent high school graduates enter the university gates; after all, it was the university teachers who sent out the high school teachers who prepared these graduates for them. So in the end it is necessary, as I said, to think the idea through to the end. And that shows us that, if with some indulgence, we may already apply the concept of guilt in a certain respect.

But today some very strange words have been said, you see. And I must say that one of the strangest words, almost one of the little piquant ones, was this: that it was said that a university teacher had said: We expect deliverance from the student body! I am just surprised that he did not also say: From the moment we sit down on the school benches and promote the students to the professorship. You see, it is necessary to follow up the worn-out judgments that are buzzing around the present and that are nevertheless the cause of our current conditions. Of course, in doing so, one does not fail to recognize that there are exceptions and exceptions everywhere, and one can, for example, subscribe to much, very much, of what has been said with regard to art instruction at the academies. But on the whole, one must say that there is not so much reason to have good hopes for the future if one is not prepared to join forces, not only externally, through some association or the like, to join forces to move towards some vague goal, but when one is prepared – only when one is prepared – to truly engage in a thorough renewal and revival of our spiritual life itself. The actual damage is already encroaching on our spiritual life itself. And anyone who is familiar with the whole structure of anthroposophical life, how it has led, for example, to this School of Spiritual Science, certainly does not need to be told that “everyone must be free to express their worldview and to speak out of their own free conviction!” The many malicious natures who are here today to say all kinds of inaccurate things about the anthroposophical movement and related matters will immediately take advantage of this and say: These anthroposophists want their world view to be represented everywhere.

Now, the Waldorf school was founded by our community, without in any way founding a school of world view. The opposite of a world view school should be founded. This has been emphasized time and again. And anyone who believes that the Waldorf school is “an anthroposophical school” does not know it at all. And nor can it be said here at the Goetheanum that anyone is restricted in their free expression of their most deeply held convictions.

But what I will always fight for, despite all freedom, individuality and intellectualism, is scientific conscientiousness, thoroughness, being informed about what one is writing about, not just putting forward one's own opinion because one believes that under certain circumstances damage could arise from something that one has not really taken the trouble to understand, and from which one has plucked a few sentences in order to write an article.

I say this quite dispassionately. You know that I usually use the things that are done as “reviews” of anthroposophy only as a proximate occasion to characterize general conditions. I am not really interested in the personal attacks, only to the extent that they point to what needs to be changed in our circumstances. And here I do believe that the fellow student from Bonn, in his hearty way, has struck the right note, a right note to the extent that the students he meant really cannot find what they are looking for at the universities or colleges today.

But not “because of the curriculum”, not “because the right choices are not being made”, but because today's youth quite instinctively – without being fully aware of it – craves something from the bottom of their hearts that is not yet present within the general scientific framework, but which must be created within the general scientific framework. This is what awaits young people. This youth will certainly not fail to grasp with both hands when it is offered what it really wants: a truly new spirit. For such a new spirit is needed in the present.

This is basically the reason for the aversion to what emanates from anthroposophical spiritual science, even if one uses the phrase “one wants to accommodate every new thing”. When it asserts itself, then one does not do it after all. Because basically one cannot do it at all. It would be of no use to conceal these things in any way, but rather they must be pointed out clearly and distinctly.

Then the question of the World School Association was raised here. I believe I expressed very clearly what I have to say about this World School Association in terms of its intentions at the end of our last School of Spiritual Science course here in the fall. I then again expressed in roughly the same way the necessity of founding such a general world school association in The Hague, in Amsterdam, in Utrecht, in Rotterdam and in Hilversum: that the possibility of working in a world school association depends on the conviction that a new spirit must enter into the general school system spreading in as many people as possible. I have pointed out that today it cannot depend on founding schools here or there that would stand alone and in which a method is applied that is widespread in this or that respect, but that the school system of modern civilization must be taken into hand on the basis of the idea of a self-supporting, liberated spiritual life, the school system for all categories, for all subjects.

As far as I am aware, the words and calls that I have spoken so far are the only things I have to report on. These words were intended to find an echo in the civilized population of the present day. I have no such response to report. And I think the fellow student from Bonn spoke a true word when he pointed out that ultimately the student body from whose hearts he spoke here is in the minority. I think it is very, very much in the minority, especially in Germany. But also otherwise – I don't want to be unkind to anyone – otherwise, from where we are not far away at all. This is shown by the attendance at this college course. He said: the majority of the student body is asleep! Yes, it also rages at times. But one can also sleep while raging with regard to the things at stake.

And with regard to the matters for which this demand for the World School Association has been raised, everyone is also sleeping peacefully in the broadest circles. And it must be said: people have not yet really become accustomed to how necessary it is to bring anthroposophical work into modern civilization. We must become accustomed to it, and I long for the day when I can report more fully on the question of the world school association. Today I still could not say much more than what I said at the end of the School of Spiritual Science courses here last fall, although what I said was intended to allow something completely different to be reported today.

But the same applies to other things, and it is very difficult to raise awareness of the issues that really matter in today's world.

In a lecture in Berlin, after Lloyd George had called a general election in England in the wake of a strike that had already broken out, I pointed out that you don't achieve anything with such things, that it's just a postponement. It seems that people took it as a mere catchphrase at the time. Now, please, see for yourself today, you could have done so for a few days already, whether what I said back then was just a catchphrase or whether it was perhaps born out of a deeper understanding of social interrelations and the necessity of social interrelations.

The difficulty is that today there are so few people with the enthusiasm that really makes them feel inwardly involved with what they are saying. And so I am always pleased when young people come forward who have something to say about how they find what they are looking for here or there. For I believe that from such impulses will emerge what we need for all insight, for all understanding: inner participation, inner participation that knows how strong the metamorphosis must be that leads us from the declining forces of an old civilization to the impulses of the new civilization. Yes, we need conscientious understanding, we need penetrating insight. But above all, we need what youth could bring out of its natural abilities. But we need not only insight, not only penetrating understanding of the truth, in the broadest circles of present-day civilized humanity, we need enthusiasm for the truth!

Mathematik und Anorganische Naturwissenschaften

Wenn ich heute versuche, den Übergang zu machen vom eigentlichen philosophischen Gebiete in das Gebiet der speziellen Fachwissenschaften, so ist dieser Übergang in unserer gegenwärtigen Zeitepoche ganz naturgemäß über eine Anschauung des mathematischen und des physikalischen, chemischen, das heißt des anorganischen Naturgebietes zu bewerkstelligen: weil weitaus die meisten der gegenwärtigen philosophischen Vorstellungen so aufgebaut sind, daß die Philosophen ihnen das zugrunde legen, was sie an Begriffen und Ideen aus jenem Wissenschaftsgebiet gewonnen haben, das heute als das sicherste gilt, aus dem mathematischen und dem der anorganischen Naturwissenschaft.

Wenn man die heute so beliebte mathematische Behandlung des Gebietes der anorganischen Naturwissenschaften besprechen will, muß immer wiederum an etwas erinnert werden, das schon in der Eröffnungsrede erwähnt worden ist: an die Anknüpfung, welche das gegenwärtige Denken glaubt an Kant machen zu können gerade mit der Einführung der Mathematik in die anorganischen Naturwissenschaften, ja, in die Wissenschaft überhaupt.

Worauf in diesem und auch in einem späteren Zusammenhange von der negativen Seite her, ich sage ausdrücklich von der negativen Seite her, wird aufmerksam gemacht werden müssen, das wurde auch schon bemerkt von einzelnen Denkern, die sehr weit abstehen von dem Gebrauche übersinnlicher Erkenntnisse. So wird man das Negative, das heißt das Zurückweisen des rein mathematischen Behandelns der Naturwissenschaft, zum Beispiel selbst bei einem Denker wie Fritz Mauthner, ganz trefflich finden, wie er aus einem gewissen Scharfsinn heraus in negativer Beziehung, das heißt im Zurückweisen desjenigen, was als falsche Ansprüche einer falschen Wissenschaftlichkeit auftritt, durchaus nicht unglücklich ist. Und in bezug auf die Frage: Was kann die gegenwärtige Wissenschaft nicht? — kann man gerade von einem Denker wie Fritz Mauthner viel lernen, lernen durch das Negative, das er vorbringt, und lernen durch die Tatsache, daß er bei diesem Negativen stehenbleiben, durchaus nicht vorwärtsdringen möchte zu einer positiven Erkenntnis.

Warum sollten Sie nicht auch von einem solchen negativen Denker lernen? Wenn ich gestern den Ausspruch Ludwig Hallers anführen konnte, daß nach seiner Meinung Kant dem Arsenal des Lichtes die Waffen entnommen habe, um sie im Dienste der Finsternis zu verwenden, warum sollten Sie nicht auch dem Arsenal der Finsternis, sogar der gewollten Finsternis des Erkennens, wie sie sich bei Fritz Mauthner findet, die Waffen entlehnen, um sie im Dienste des Lichtes zu verwenden?

Aufmerksam ist, wie gesagt, auf jenen Ausspruch Kants zu machen, der lautet, es finde sich in jeder einzelnen Disziplin nur soviel eigentliche Wissenschaft, als Mathematik darin anzutreffen ist.

Wenn man die Geschichte der Verwendung dieses Kantischen Ausspruches bis in unsere Tage herein studiert, dann bekommt man ein interessantes Beispiel zur Beantwortung der Frage, wie man überhaupt in der neueren Zeit Kantianer ist. Denn die Leute, die sich auf diesen Ausspruch berufen, meinen, daß in jede einzelne Wissenschaft so viel wirkliche Wissenschaftlichkeit hineingetragen werde, als Mathematik darinnen ist. Kant meint aber etwas ganz anderes. Kant meint: so viel er Mathematik in die Wissenschaft hineinträgt, so viel ist eben Mathematik, das heißt wirkliche Wissenschaft drinnen, und das andere ist eben in den einzelnen Wissenschaften überhaupt gar keine Wissenschaft.

Sie sehen, man wird Kantianer, wenn man einen Kantischen Ausspruch gründlich mißversteht. Denn die Kantschaft auf diesem Gebiete hat etwa die folgende Logik: Wenn ich sage, in einer Versammlung, in der tausend Menschen sind, ist so viel Genialität darinnen, als drei geniale Menschen hineingetragen haben, so meine ich ganz gewiß nicht, daß die tausend Menschen nun die Genialität der drei Menschen übertragen bekommen haben. Ebensowenig meint Kant, daß das übrige in der Wissenschaft die Wissenschaftlichkeit der Mathematik bekommen habe; sondern er meint eben, daß nur der kleine Teil, der auch in den Wissenschaften Mathematik geblieben ist, wirkliche Wissenschaft, das andere aber überhaupt keine Wissenschaft ist.

Man muß solche Dinge im Ernste — und in einem empirischen Zeitalter sollte man das empirisch, nicht a priori tun — studieren, damit sich solche Fragen nicht so beantworten, wie es heute vielfach geschieht, sondern damit man der Wahrheit auf die Spuren kommt.

Nun kann man aber noch auf etwas anderes hinweisen: Die hervorragendsten mathematischen Denker der neueren Zeit definieren die Mathematik etwa so: sie wäre die «Wissenschaft von den Größen». Nun ja, heute ist sie die Wissenschaft von den Größen. Aber man gehe nur ein paar Jahrhunderte zurück in die Zeit, in welcher Cartesius und Spinoza eine große Befriedigung daran gefunden haben, ihre Philosophie «nach mathematischer Methode» darzustellen, wie sie sagen, und man wird finden, daß es etwas ganz anderes ist, was Cartesius und Spinoza als mathematische Methode in ihre Philosophie hineinbringen wollten als dasjenige, was in der neueren Zeit als Mathematik in die Naturwissenschaft hineingetragen werden soll.

Gehen wir bis zu Cartesius und Spinoza zurück, dann finden wir, daß diese beiden Philosophen ihr philosophisches System so aufstellen wollen, daß eine ebenso große Sicherheit im Übergang von einem Satz zum anderen herrscht, wie sie in der Mathematik herrscht. Das heißt, sie wollen ihre Philosophie aufbauen nach dem Muster dieser mathematischen Methoden; aber nicht, sie wollen in ihre Philosophie das hineintragen, was man heute unter Mathematik versteht. Da haben wir also bereits, indem wir so zu Cartesius und Spinoza zurückgehen, mit dem Worte Mathematik einen ganz anderen Sinn verknüpft. Wir haben — mit Absehen von dem, was sich bloß auf Größen bezieht — den Sinn verknüpft des inneren sicheren Übergehens von Urteil zu Urteil, von Schluß zu Schluß. Wir haben die Art des mathematischen Denkens ins Auge gefaßt, nicht das, was wir eine Größenwissenschaft nennen können.

Und gehen wir noch weiter zurück. Dann bekommt in älteren Zeiten das Wort «Mathematik» überhaupt einen ganz anderen Sinn. Dann ist es identisch mit dem Worte Wissenschaft. Das heißt, man hat, wenn man «Wissenschaft» gemeint hat, von «Mathesis» oder «Mathematik» gesprochen, weil man im Mathematisieren die Sicherheit des inneren Durchschauens eines im Bewußtsein vorhandenen 'Tatbestandes fand. Man verband mit diesem Worte den Sinn «Wissen» und «Wissenschaft». Und so ist ein viel allgemeinerer Begriff auf das enge Gebiet der Größenlehre übertragen worden. Heute haben wir alle Veranlassung, uns an solche Dinge zu erinnern, weil wir in die Notwendigkeit versetzt sind, wiederum auf das hinzuschauen, was im mathematischen Denken eigentlich vorliegt. Was ist das Wesentliche des mathematischen Denkens? Das Wesentliche des mathematischen Denkens ist eben die Durchschaubarkeit der mathematischen Bewußtseinsinhalte. Wenn ich ein Dreieck aufzeichne, seine drei Winkel ins Auge fasse, Alpha, Beta, Gamma, und den Beweis liefern will, daß die Summe dieser drei Winkel i8o Grad ist, dann mache ich das Folgende (siehe Abbildung r): Ich ziehe zur Grundlinie eine Parallele durch den obersten Punkt des Dreiecks, betrachte mir das Verhältnis der Winkel Alpha und Gamma zu den an der Parallele entstehenden Wechselwinkeln und habe dann, indem ich überschaue, wie sich die drei Winkel, welche an der Parallele entstehen — Gamma’, Alpha’, und Beta -, aneinander lagern, und wie sie einen Winkel von i80 Grad bilden, den Beweis, daß auch die drei Winkel des Dreiecks 180 Grad sind. Das heißt, was bis in die Beweisgänge hinein im Mathematischen als Bewußtseinstatbestand vorhanden ist, das ist überschaubar, das wird vom Anfang bis zum Ende von innerlichem Erleben begleitet. Und darauf beruht die Sicherheit, die man im Mathematisieren fühlt: daß alles, was als Bewußtseinsbestand vorliegt, von innerlichem Erleben begleitet wird bis zum Urteil und bis zum Beweis hin.

Und wenn man dann die äußere Natur betrachtet, in deren materielle Grundlagen man mit einer solchen Überschaubarkeit nicht hineindringen kann, dann fühlt man sich im Betrachten der äußeren Natur dennoch befriedigt, wenn man wenigstens ihre Erscheinungen in dem Erleben verfolgen kann, das einem zuerst in der Überschaulichkeit entgegengetreten ist.

Die Sicherheit, die man in dieser Überschaubarkeit des Bewußtseinsbestandes beim Mathematischen fühlt, tritt besonders dann zutage, wenn man auf das eingeht, was von allen Seiten als ein großer Fortschritt im Mathematischen innerhalb des i9. Jahrhunderts angesehen wird: was als «nichteuklidische Geometrie», als «Metageometrie» bei Lobatschewskij, Bolyai, Legendre und so weiter hervorgetreten ist.

Da sehen wir, wie man — im Grunde genommen doch bauend auf die innere Sicherheit des Anschauens — zuerst die euklidischen Axiome abändert und durch Abänderung der euklidischen Axiome mögliche andere Geometrien als die euklidische aufbaut, und wie man dann versucht, mit dem, was man da als eine Erweiterung der Anschaulichkeit aufgebaut hat, gegenüber einer undurchschaubaren Wirklichkeit zurechtzukommen. Alle Vorstellungen, die durch diese «Metageometrie» in das moderne Denken eingezogen sind, sind im Grunde genommen ein Tatsachenbeweis für die Sicherheit, die man in dem Überschaubaren des Mathematisierens fühlt.

Und niemand wird mit Bezug auf den euklidischen Raum — denn die Räume der anderen Geometrien sind eben andere Räume -, der ja dadurch charakterisiert ist, daß drei aufeinander senkrecht stehende Koordinatenachsen bis in die Unendlichkeit hinein in ihren Richtungen aufeinander senkrecht gestellt gedacht werden müssen, daran zweifeln, daß für diesen euklidischen Raum gilt, was hier als Beweis für die 180-Gradigkeit der drei Winkel eines Dreiecks hingestellt worden ist. Und jeder wird sich klar sein darüber, daß, wenn er die euklidischen Axiome abändert, dies vielleicht Beziehung habe auf unseren Raum, in dem wir sind — der ist eben dann nicht der euklidischa Raum, der ist vielleicht ein innerlich gekrümmter Raum -, aber daß für den euklidisch überschaubaren Raum die euklidischen Resultate wegen ihrer Durchschaubarkeit als sicher angenommen werden müssen. Daran wird niemand zweifeln.

Und gerade wenn man diese Tatbestände durchschaut, dann wird man finden: die Anwendung der Mathematik auf das Gebiet der Naturwissenschaft beruht darauf, daß man in der Außenwelt das erst innerlich Gefundene wieder findet, daß gewissermaßen die Tatsachen der Außenwelt sich so verhalten, wie es den mathematischen Ergebnissen entspricht, die wir erst unabhängig von dieser Außenwelt in innerer Anschauung gefunden haben.

Aber eines ist durchaus zu konstatieren: Die, ich möchte sagen, Vorausbedingung für diese innerliche Anschauung des Mathematischen ist, daß dieses Mathematische uns zuerst als Bild entgegentritt. Jene innere freie Tätigkeit des Konstruterens, die wir im Mathematisieren erleben, ist eine solche innere freie Tätigkeit nur dadurch, daß in ihr nichts waltet von dem, was sonst innerhalb unserer menschlichen Wesenheit waltet, wenn wir zum Beispiel, einem Instinkt folgend, wollen oder dergleichen. Aus diesem ist gewissermaßen bis zur Bildhaftigkeit herausgehoben, was als Bewußtseinsbestand im Mathematisieren auftritt. Das Mathematische ist in bezug auf das, was «äußerliche Naturwirklichkeit» ist, Unwirklichkeit. Und wir fühlen die Befriedigung in der Anwendung des Mathematischen auf die Naturerkenntnis gerade dadurch, daß wir das frei in Bildlichkeit Erfaßte im Reiche des Seins wieder erkennen können.

Aber gerade daraus wird man zugeben müssen, daß es auf der einen Seite berechtigt ist, wenn solche Geister, die nicht bloß auf das gehen wollen, was die Naturwirklichkeit als solche in der menschlichen Anschauung als wirklich zeigt, sondern die auf das Volle, Totale der Wirklichkeit gehen wollen, wie Goethe, wenn solche Geister — das hat Goethe besonders bei der Behandlung der «Farbenlehre» klar gezeigt — nicht eine totale Anwendung des Mathematischen auf die ganze äußere Wirklichkeit wollen. Goethes Ablehnen der Mathematik ging gerade aus der Erkenntnis hervor, daß man zwar dasjenige, was der bildhaften Anschaulichkeit des Mathematischen entspricht, in der äußeren Natur durch Mathematik finden kann, daß man aber damit zu gleicher Zeit Abstand nimmt von allem Qualitativen. Goethe wollte bei der Behandlung der äußeren Natur nicht bloß das Quantitative, er wollte auch das Qualitative einbezogen haben.

Auf der anderen Seite aber muß man sagen, daß die ganze innerliche Größe der Mathematik auf ihrer Bildlichkeit beruht, und daß gerade in dieser Bildlichkeit dasjenige zu suchen ist, was ihr den Charakter einer apriorischen Wissenschaft gibt, einer Wissenschaft, die rein durch innere Anschauung zu finden ist.

Aber damit ist man zu gleicher Zeit, indem man mathematisiert, gerade aus dem Natursein, demgegenüber die Mathematik einen ganz besonders interessiert, eigentlich draußen. Man ergreift nirgends ein In-sich-Wirksames, sondern nur die durch die mathematischen Formeln ausdrückbaren Beziehungen dieses Wirksamen. Wenn Sie in mathematischen Formeln eine zukünftige Mondenfinsternis oder, mit Einsetzung entsprechender Größen in negativer Form, eine in früherer Zeit vorübergegangene Mondenfinsternis errechnen, so müssen Sie sich bewußt sein, daß Sie niemals in das innere Wesen desjenigen eindringen, was da geschieht, sondern nur von einem gewissen Gesichtspunkte aus die Quanten von Verhältnissen mit mathematischen Formeln umfassen. Das heißt, man muß sich klar sein, daß man niemals in das innerlich wesenhaft Differenzierte durch das Mathematische hineindringen kann, wenn man dieses Mathematische in dem engen Sinne faßt, in dem es noch heute vielfach gefaßt wird.

Aber schon sehen wir auch innerhalb des Mathematischen eine Art Weg, der aus dem Mathematischen selber herausführt. Aus dem, was ich eben gesagt habe, können Sie entnehmen, daß dieser Weg, der aus dem Mathematischen herausführt, ähnlich sein müßte dem Weg, den wir durchlaufen, wenn wir mit dem ganz bildhaft Mathematischen, mit dem undurchkrafteten, unwirksam bildhaften Mathematischen nun untertauchen in die durchkraftete und durchkraftende Natur. Da tauchen wir in etwas unter, was uns gewissermaßen mit unserer freien mathematisierenden Tätigkeit abfängt und die mathematischen Formeln in ein Geschehen einzwängt, das in sich wirksam ist, das in sich etwas ist, von dem wir uns sagen müssen: wir kommen nicht vollständig heran mit dem Mathematischen; das Ding behauptet gegenüber der innerlichen Durchschaubarkeit des Mathematischen seine wesenhafte Selbständigkeit und sein wesenhaftes Innensein.

Dieser Weg, der da gegangen wird, wenn man einfach den Übergang sucht von der irrealen mathematischen Denkungsart zu der realen naturwissenschaftlichen Denkungsart, kann in einer gewissen Weise heute schon innerhalb des Mathematischen selber in einer gewissen Beziehung gefunden werden. Und wir sehen, wie er gefunden werden kann, wenn wir nicht äußerlich, sondern innerlich die Versuche betrachten, welche das Denken gemacht hat beim Übergang von der bloß analytischen Geometrie zu der projektivischen oder synthetischen Geometrie, wie sie die neuere Wissenschaft vorstellt. Ich möchte an einem ganz elementaren, an einem allerelementarsten und bekanntesten Beispiel der synthetischen Geometrie erläutern, was ich mit dem eben ausgesprochenen Satze meine.

Wenn man synthetische, neuere projektivische Geometrie treibt, so unterscheidet man sich von dem analytischen Geometer dadurch, daß der analytische Geometer mit mathematischen Formeln rechnet, daß er also rechnet, daß er zählt und so weiter. Als synthetischer Geometer benützt man - ich meine das jetzt natürlich ideell - nur das Lineal, den Zirkel und das, was durch Lineal und Zirkel im Bewußtsein als Tatbestand auftreten kann, was aus der Anschauung zunächst hervorgeht. Fragen wir uns aber, ob es auch rein innerhalb der Anschauung verbleibt.

Denken wir uns eine Linie — was man in der gewöhnlichen Geometrie eine Linie nennt — und auf dieser Linie drei Punkte. Dann haben wir das folgende mathematische Gebilde (siehe Abbildung 2): eine Linie, auf der sich die drei Punkte I, II, III befinden.

Es gibt nun — ich kann, was ich hier anzuführen habe, natürlich nur in den Hauptlinien andeuten, gewissermaßen appellierend an das, was Sie über die Sache schon wissen — ein anderes Gebilde, welches in einer gewissen Weise in seiner ganzen Konfiguration entsprechend ist diesem eben aufgezeichneten mathematischen Gebilde Und dieses andere Gebilde entsteht dadurch, daß ich drei Linien in einer ähnlichen Weise behandle, wie ich diese drei Punkte hier behandelt habe, und daß ich einen Punkt in einer ähnlichen Weise behandle, wie ich hier die Linie behandelt habe. Denken Sie sich also, ich zeichne statt der drei Punkte ], II, III, drei Linien an die Tafel, und statt der Linie, welche durch die drei Punkte geht, zeichne ich einen Punkt (siehe Abbildung 3); und damit eine Entsprechung entstehe, nehme ich den Punkt, in dem sich die drei Linien schneiden: Ich habe hier ein anderes Gebilde gezeichnet (Abb. 3). Der Punkt, den ich oben mit einem kleinen Ringelchen gezeichnet habe, entspricht der Linie links, die drei, wie man sie nennt, Strahlen, die sich in einem Punkt schneiden, und die ich mit I, II, III bezeichne, die entsprechen den drei Punkten I, II, III, die auf der Linie links liegen (Abb. 2).

Sie müssen, wenn Sie das ganze Gewicht dieses eben ausgesprochenen Urteiles empfinden wollen, genau den Wortlaut nehmen, wie ich ihn eben ausgesprochen habe. Sie müssen sagen: der Punkt rechts (Abbildung 3), den ich oben mit einem kleinen Ringelchen bezeichnet habe, entspricht der Linie links (Abbildung 2), auf der die drei Punkte liegen; und die Strahlen I, II, III rechts entsprechen den Punkten ], II, III links. Und indem sich die drei Strahlen I, II, III rechts in dem einen Punkt oben schneiden, entspricht dieses ihr Schneiden dem Liegen der drei Punkte links I, II, III auf der links gezeichneten geraden Linie.

So ausgesprochen, liegt ein ganz bestimmter Bewußtseinstatbestand vor und ein entsprechendes Gebilde links gegenüber dem Gebilde rechts.

Man kann nun — indem man zunächst rein innerhalb desjenigen bleibt, was anschaulich ist, was sich also konstruieren läßt mit Zirkel und Lineal, wozu kein Rechnen nötig ist— zu dem folgenden Bewußtseinstatbestande übergehen: Ich zeichne links noch einmal eine Linie, und noch einmal auf dieser Linie drei Punkte (die untere Linie in Abbildung 4).

Ich habe nun - ich bitte, jetzt ganz genau die Ausdrucksweise, die ich befolgen werde, als maßgeblich zu betrachten für den Tatbestand -, ich habe nun links die Linie gezeichnet, auf welcher sich die drei Punkte i, 2, 3 liegend befinden. Ich werde weitergehen und nehme an - bitte wohl zu beachten das Wort, das ich ausspreche: «und nehme an» —, ich werde weiter das Folgende tun und nehme dann etwas an. Ich werde in einer gewissen Weise die Punkte links von der einen Linie mit den Punkten von der anderen Linie verbinden und werde dadurch Verbindungslinien bekommen, die sich schneiden werden (siehe Abbildung 5). Ich werde verbinden links in meinem Gebilde den Punkt I mit dem Punkt 3, den Punkt III mit dem Punkt i, den Punkt I mit dem Punkt 2, den Punkt II mit dem Punkt 1, den Punkt III mit dem Punkt 2, den Punkt II mit dem Punkt 3, und werde durch diese Linien Schnittpunkte bekommen, die ich dann wiederum — ich nehme es jetzt an — durch eine gerade Linie verbinden kann. Also meine Konstruktion sei in anschaulicher Durchsichtigkeit so ausgeführt, daß ich das wirklich vollziehen könne, was ich jetzt angegeben habe. Man kann nämlich diese Konstruktion so ausführen (punktierte Linie in Abbildung 5): Sie sehen, ich habe die drei Schnittpunkte, die ich auf die vorhin beschriebene Weise bekommen habe, so bekommen, daß ich durch sie die hier strichpunktierte Gerade ziehen kann.

Ich nehme nun an, daß ich, indem ich zu dem rechten Strahlenbüschel (Abbildung 3), so nennt man es, ein anderes hinzufüge, daß ich in dem Verhältnis der Ausstrahlung dasselbe Verhältnis drinnen habe wie in der Entfernung der auf der linken Geraden liegenden Punkte. Ich werde also ein zweites Strahlenbüschel rechts hineinzeichnen (Abbildung 6), das in bezug auf seine Ausstrahlungsverhältnisse den Lagenverhältnissen der Punkte auf den Linien links entspricht. Ich habe also hier (Abbildung 6) ein anderes Strahlenbüschel hineingezeichnet und nenne es 1, 2, 3, indem ich annehme, daß 1, 2, 3 in bezug auf die Strahlen rechts entspricht 1, 2, 3 in bezug auf die Punkte links.

Und ich werde jetzt die entsprechende Prozedur bei meinen zwei Strahlengebilden rechts ausführen, die ich links (Abbildung 5) bei meinen Linien- und Punktgebilden ausgeführt habe, nur muß ich berücksichtigen, daß einer Linie links ein Punkt rechts entspricht: während ich links eine Linie gesucht habe, die zwei Punkte verbindet, muß ich rechts einen Punkt suchen, der entsteht, indem zwei Strahlen sich schneiden. Das Schneiden rechts soll entsprechen dem Verbinden links (die Schnittpunkte in Abbildung 6 werden durch kleine Kreise markiert, siehe Abbildung 7). Sie sehen, was ich gemacht habe: wenn ich links III mit i und 3 mit I als Punkte verbunden habe, habe ich hier rechts I mit 3 und i mit III als Linien zum Schnitt gebracht.

Und wenn ich links zwei Linien gezogen habe von Punkten aus und sie zum Schnitt gebracht habe in einem Punkt, so werde ich jetzt entsprechend rechts durch die beiden Punkte, die ich bekommen habe, eine Linie ziehen (strichliert in Abbildung 7), und ich werde dieselbe Prozedur mit Bezug auf die anderen Strahlen jetzt ausführen. Das heißt [der Vortragende verdeutlicht nochmals die Entsprechung der geringelten Schnittpunkte von Abbildung 7 mit den Verbindungslinien von Abbildung 5], ich werde II mit i zum Schnitt bringen, I mit 2, III mit 2, II mit 3; ich werde also rechts die Schnittpunkte suchen, wie ich links die Verbindungslinien gesucht habe; und, wie Sie sehen, habe ich rechts durch das Zum-Schnitt-Bringen der Strahlen diese Schnittpunkte gesucht, um Linien durch diese Schnittpunkte zu ziehen (strichliert in Abbildung 7), wie ich links durch das Verbinden der Punkte Linien gesucht habe, um die Schnittpunkte dieser sich schneidenden Linien zu gewinnen (geringelt in Abbildung 5).

Die Verbindungslinien- aber der Schnittpunkte, die ich rechts gewonnen habe, schneiden sich ebenso in einem hier durch ein Ringelchen bezeichneten Punkt oben (P in Abbildung 7), wie die drei Punkte, die ich links bekommen habe, in einer geraden Linie liegen (strichliert in Abbildung 5). Das heißt, im Gebilde rechts, wo statt der Punkte Linien, statt der Verbindungslinien Schnittpunkte sind, bekomme ich, wie ich links eine Linie bekommen habe, die durch die drei Punkte geht, einen Punkt, in dem sich die drei Geraden schneiden. Ich bekomme rechts wiederum einen Punkt für die Linie links.

Hier bleibe ich, indem ich rein vom Gebiete des Anschaulichen ausgehe, zwar innerhalb desjenigen, was von der Anschauung ausgeht, was aber doch zu etwas anderem führt. Und ich bitte Sie, das Folgende zu berücksichtigen. Nehmen Sie an, Sie schauen in der Linie, in der Richtung, die angegeben wird durch die (gestrichelte) Linie links, die durch die drei Schnittpunkte — Alpha, Beta, Gamma geht, dann werden Sie auf einen Schnittpunkt aufschauen, der die anderen verdeckt, gegenüber dem die anderen hinter ihm sind (Abbildung 8). Sie haben hier, in der Linie auseinandergelegt, nicht nur «drei Punkte». Sondern sobald man zu einem Wirklichkeitsverhältnis übergeht, tritt gegenüber diesen drei Punkten etwas auf, was ganz anschaulich ist: der Punkt Gamma ist der Vordere, und hinter ihm sind die Punkte Beta und Alpha. Das haben Sie in der linken Figur klar auseinandergelegt in der Anschauung.

Gehen wir jetzt durch eine ganz gesetzmäßige Prozedur, die ich beschrieben habe, über zu dem rechts entsprechenden Gebilde, so haben wir statt der Linie einen Punkt ins Auge zu fassen (P in Abbildung 9). Wenn wir ihn ins Auge fassen, so müssen wir sagen, geradeso wie links durch die Verbindung von III mit 2 und die Verbindung von 3 mit II ein Schnittpunkt entsteht, Gamma, der die anderen Schnittpunkte zudeckt, so daß das Verhältnis entsteht: Gamma ist vorn, Alpha ist hinten, so entsteht rechts die Notwendigkeit, das Folgende vorzustellen und damit, durch das Verbindungsgesetz, aus dem Anschaulichen ins Unanschauliche überzutreten: Rechts (Abbildung 9) entsteht die Notwendigkeit, den geringelten Punkt (P) so vorzustellen, daß der Strahl (Gamma), der durch die Verbindung der Schnittpunkte der Linien III und 2, II und 3, entsteht, sich zunächst in dem geringelten Punkt mit demjenigen Strahl (Beta) schneidet, der durch das voranliegende Verhältnis (III mit 1, I mit 3) entsteht; und wir müssen uns vorstellen, daß innerhalb dieses geringelten Punktes die Schnitte, die durch die drei strichlierten Strah 76 len entstehen, ebenso als drei innerlich differenzierte Entitäten liegen wie links auf der strichpunktierten Linie die drei Punkte Gamma, Beta, Alpha. Das heißt, ich muß die Schnitte rechts im einzelnen Punkt so angeordnet finden, daß sie sich übereinander decken.

Das heißt mit anderen Worten nichts Geringeres als: Geradeso wie ich für ein hinschauendes Auge die strichpunktierte Linie links so zu denken habe, daß für die Punkte Gamma, Beta, Alpha ein Vorne und Hinten entsteht, so habe ich innerhalb des Punktes, das heißt einer Raumausdehnung von Null, nach allen drei Dimensionen eine Differenzierung zu denken. Ich habe in diesem Punkte - angeschaut aus der Art heraus, wie er aus diesem Gebilde entstanden ist — nicht etwas Undifferenziertes, sondern ein Vorne und Hinten zu denken. Ich bekomme hier die Notwendigkeit, einen Punkt nicht neutral nach allen Seiten zu denken, sondern den Punkt zu denken mit einem Vorne und Hinten.

Ich mache hier einen Weg, durch den ich aus dem freien Bilden des Mathematischen hineingezwungen werde in etwas, wo das Objektive zu einer Eigenbestimmung, zu einem Innensein übergeht. Sie sehen, dieser Weg ist ähnlich demjenigen, durch den ich übergehe von dem mathematisch freien Bilden zu dem In-Empfang-Nehmen dieses Bildens vom innerlichen Bestimmtsein innerhalb der Naturordnung. Und ich bekomme, indem ich von der analytischen zu der synthetischen Geometrie übergehe, den Anfang des Weges, der mir gezeigt wird von der Mathematik zur anorganischen Naturwissenschaft.

Es ist dann im Grunde genommen nur noch ein kleiner Weg zu etwas anderem. Man kann, indem man diese Erwägungen, auf die ich jetzt hingedeutet habe, fortsetzt, zum innerlichen Begreifen auch des folgenden Bewußtseinstatbestandes kommen: Wenn man rein mit Hilfe der projektiven, der synthetischen Geometrie verfolgt, wie sich ein Hyperbel zu einer Asymptote verhält, so bekommt man rein anschaulich heraus, daß nach der einen Seite, sagen wir rechts oben, die Asymptote sich dem Hyperbelast nähert, aber ihn niemals erreicht, daß man aber dennoch die Vorstellung bekommt, die Hyperbel komme wiederum von links unten zurück mit dem anderen Ast, und die Asymptote komme ebenfalls von links unten zurück mit ihrer anderen Seite. Mit anderen Worten: ich bekomme durch dieses Verhältnis von Asymptote zur Hyperbel etwas, was ich etwa in der folgenden Art Ihnen auf die Tafel zeichnen könnte (Abbildung 10): Rechts oben geht die Asymptote, die gerade Linie, immer näher an die Hyperbel heran. Ich habe dort eine Schraffierung hinzugefügt, um auszudrücken, was für ein Verhältnis die Asymptote eigentlich zum Hyperbelast hat. Sie kommt ihm immer näher, sie will an ihn heran, sie kommt immer näher und näher in das Sein ihres Verhältnisses zu ihm hinein. Wenn man nun dieses Verhältnis verfolgt nach rechts oben, so kommt man zuletzt durch rein projektives Denken — ich kann das hier nur andeuten — dazu, die Richtung der Linie, die man nach rechts oben hat, sei es die Hyperbel, sei es die Asymptote, von links unten wieder herkommend, zu finden, den Hyperbelast und die Asymptote, und diese so, daß sie mit ihrem Sein in der schraffierten Andeutung den Hyperbelast immer mehr und mehr verläßt.

So daß wir sagen können: diese Asymptote hat eine merkwürdige Eigenschaft. Indem sie nach rechts oben hinansteigt, wendet sie sich mit ihrem Verhältnis zur Hyperbel der Hyperbel zu, indem sie von links unten wieder heraufkommt, wendet sie sich mit ihrem Verhältnis zur Hyperbel von der Hyperbel ab. Diese Linie, die Asymptote, hat, wenn ich sie in ihrer Vollständigkeit, Totalität betrachte, wiederum ein Vorne und Hinten. Deshalb konnte ich auch die Schraffierung das eine Mal auf der einen Seite, das andere Mal auf der anderen Seite zeichnen. Ich komme wiederum in eine innere Differenzierung des Linearen hinein, wie ich in eine innere Differenzierung hineinkomme, wenn ich das rein mathematisch Bildhafte in das Gebiet des Naturgeschehens hineindränge. Das heißt, ich nähere mich dem, was als Differenzierung im Naturgeschehen auftritt, wenn ich in richtiger Weise mit Hilfe der projektiven Geometrie die mathematischen Gebilde selbst erfassen will.

Was da durch die projektive Geometrie geschieht, das kann niemals in derselben Weise durch die bloße analytische Geometrie gemacht werden. Denn die bloße analytische Geometrie bleibt, indem sie also in Koordinaten konstruiert und dann in ihrer Rechnungsform die Endpunkte der Abszissen und Ordinaten aufsucht, mit dem, was sie konstruiert, in ihrer Form ganz außerhalb der Kurve oder außerhalb des Gebildes selber stehen. Die projektive Geometrie bleibt nicht außerhalb der Kurve und des Gebildes stehen, sondern sie dringt in die innere Differenzierung des Gebildes: bis zum Punkte, bei dem man unterscheiden muß ein Vorne und Hinten — bis zur Geraden, bei der man ebenfalls unterscheiden muß ein Vorne und Hinten. Ich habe nur diese Eigenschaften wegen der Kürze der Zeit angegeben, ich könnte noch andere Eigenschaften angeben, zum Beispiel ein gewisses Krümmungsverhältnis, das der nach den drei Raumdimensionen ausgedehnte Punkt in sich hat und so weiter.