The Origin and Development of Eurythmy

1918–1920

GA 277b

27 April 1920, Dornach

Translated by Steiner Online Library

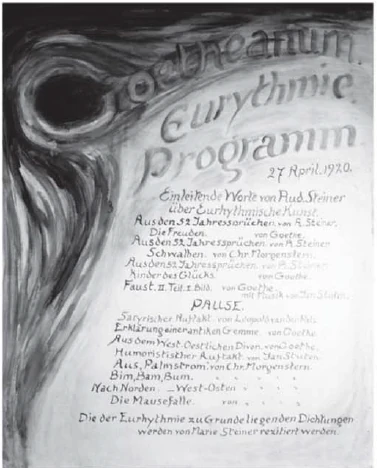

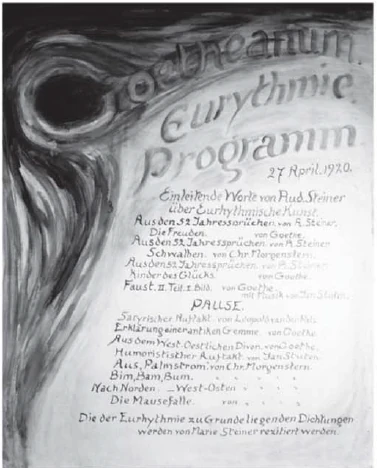

62. Eurythmy Performance

This performance was specially organized for visitors to the Swiss Trade Fair in Basel. Pastor H. Nidecker-Roos reported on it in the Christlicher Volksbote für Basel (No. 23/1920) on June 9, 1920: “On large posters, visitors to the Mustermesse in Basel were invited to visit the sanctuary of the so-called Anthroposophists, which was nearing completion, and to attend the subsequent ‘Eurhythmic Games’. [...] In front of the large main entrance, the approximately 300 visitors gathered around the striking figure of Dr. Steiner, who vividly resembled a priest. He had not only designed the building down to the last detail, but, to use his own words, had also “felt” it. The explanation of the building was at the same time an introduction to the main ideas of anthroposophy. [...] This was followed by the 'Eurhythmic Games' ('eurhythmic' can be translated as 'in well-measured time'). The idea is as follows: when speaking, the human larynx performs certain movements in which the will that is expressed in language is revealed. These movements are to be transferred to the whole body through a more serious form of individual dance, and so the whole person is to be a single expression of the spoken word. About thirty daughters, dressed in white and wearing colored veils, danced in this way, among other things, the first scene of the second part of Goethe's Faust, recited by Mrs. Steiner, as well as various poems by Goethe, Morgenstern and Steiner. The attempt was very successful in several numbers. There is nothing theatrical about the dances. They are serious attempts to express speech and soul processes through the movements of the body. The impression of the plays is one of seriousness, of a thoroughly spiritual nature.

Dear guests!

As I always do before these eurythmy performances, I would like to say a few words by way of introduction. These introductory words should never be used to comment on or explain the art of eurythmy in any real sense; that would be unartistic from the outset. For everything that is truly artistic must justify itself through itself before the act of beholding it, before the direct impression. But with eurythmy, as it is cultivated here, something new is being attempted, both in terms of artistic sources and in terms of artistic formal language, which cannot be directly compared with any neighboring arts, dance arts and the like. And so it is necessary to say something in advance about the sources and the particular way of expression of this eurythmic artistic experiment.

You will see, ladies and gentlemen, all kinds of movements performed on stage by individual people through their limbs – mainly through arms and hands, but also with the other physical limbs – and you will see movements of the individual human being in space, movements and mutual positioning of groups of people, and so on. These are not arbitrary gestures, invented in the moment out of some random fantasy. What underlies the eurythmic presentation always includes something poetic or musical, especially in what you encounter as eurythmy, where you are really dealing with a silent language, a language that uses only different means than our ordinary spoken language. Nothing arbitrary is expressed in it.

If I wish to characterize what has been attempted here, I may truly speak of Goetheanism, for everything that is connected with the spiritual current that is renewed by this structure is Goetheanism in its further development. For I need only recall a word that Goethe often used and that is particularly apt for the kind of artistic nature that underlies eurythmy: I would like to recall Goethe's words about sensuous-supernatural vision. It is through this sensuous-supernatural vision that the forms of movement of the mute language of eurythmy are gained.

You know that in our ordinary lives, even when enjoying poetry or song, we turn our attention to the tone and the sound of speech or song, and that we naturally have no idea of the movements that the larynx and the other speech organs carry out in order to produce speech. Now, the first thing to be considered is that, through sensory-supersensory observation, one can indeed obtain clear images of what takes place as movement while we turn our attention to the sound. But that is not what underlies eurythmy directly. Instead, all these movements, which are small vibrational movements that are transmitted through the special arrangement of the larynx and the other speech organs to the air, all these small vibrational movements are based on movement tendencies, and these movement tendencies can be observed. These tendencies, which are by no means arbitrary but are connected with our organism in a lawful way, in that it is a speech organism, these lawful movements can be transferred from the localized speech organ to the whole human being.

Goethe's principle of metamorphosis – although individual thinkers as early as the 19th century were trying to get to the bottom of this idea of metamorphosis, it is still not sufficiently incorporated into our intellectual life. For it will be seen that while it is still more or less accepted today as a formalistic principle, it will be seen how a true realization of the principle of metamorphosis opens up an understanding of the living world and how one can then transfer directly into the artistic that which underlies the principle of metamorphosis underlies the metamorphosis principle, which Goethe expressed not as a mere image but as a profound natural principle of formation, that the whole plant is an intricate leaf, that each plant is a transformed, a metamorphosed form of another form, the leaf form.

Transposing these forms into art shows that the whole person carries out movements that are otherwise movement tendencies in the individual organs of the larynx and its neighboring organs; in a sense, what you see on the stage would be the whole person as a moving larynx, I would say. Nothing arbitrary, nothing pantomimic, nothing mimetic - just as little as language itself is mimetic or pantomimic. Of course, in detail it passes over into one or other; but just as little as it is mimetic or pantomimic as a whole, so little is that which presents itself here as eurythmy something pantomimic or mimetic or consists in random gestures. Just as music, even in its melodious element, is a lawful succession of sounds and sound images, so here everything consists in the lawful succession of movements.

However, one must look a little into the artistic striving of the present, into the strange artistic search, if one wants to find what is being striven for with this eurythmy. In a sense, it goes back to the very origins of artistic creation, in that the human being himself - but the whole human being - is called upon as a means of artistic expression, a truly artistic means of expression. The human being himself becomes the artistic tool, and the movement possibilities inherent in him become the artistic language of form.

Today, because much that is artistic has become conventional, people are seeking to return to the original, elementary artistic sources. In poetry, there is a tendency – very, very much so, actually, can be felt already (?), and especially the civilized languages have to transfer the linguistic element more and more into the prosaic, we need the conventionality of language as a lingua franca, we need our other insights and so on – [there is a tendency] to express the forms of our technology. We need the conceptual and the ideational in language – precisely because language continues to develop, it becomes more and more the vehicle of ideas, thoughts, and conceptions, and in so doing, it distances itself from the artistic. For the death of everything artistic is the ideational, the conceptual. The artistic must be felt directly – admittedly as something profound, but not as something conceptual – from the image in human language. As it emerges from the larynx, the thought element and the will element unite out of the human being, but now, if I may use the trivial but apt expression, what shoots out of the whole human being is what the larynx accomplishes, there united as a will element with the thought element.

When we now turn to eurythmy, we leave the conceptual element, even of poetry, only as a companion. And in what is presented on stage, only the movements of the individual and the groups of people express the will element. The whole human being is transformed into movement. Anyone who has a sense of how our individuality must develop in language – I would say it becomes something rigid. We all feel, when we speak, if we have a sense for it, we all feel, when we speak, that we have to speak ourselves into a language that does not just come from our individuality. What arises individually from us must travel on the waves of the vernacular and so on. You feel that. You feel how the individual does not always want to be included. And anyone who does not feel that is not a whole person, at least not an artistic nature; because the artistic nature wants to shape the individual.

In a sense, by reproducing in eurythmy what is to be presented artistically, we stop what lives in the human being earlier than phonetic language can stop it. For example, Schiller always had a melody or an indefinite, nebulous sequence of melodies in mind first when writing his most significant poems, and only then did he add the actual words. This shows how he perceived the musical element, which is actually the artistic element of language. Or you could say: the plastic quality that lies behind speech is what is artistic.

Today, in an unartistic age, we actually place a great deal of value on the literal, including in poetry. In the age of German Romanticism, people liked to sit down together and listen to poems that had very precisely formed verses in languages that they did not understand, or at least found it difficult to understand, because in those days, in a more artistic age, people were more sensitive to rhythm, meter, to everything that is actually artistic in language. And Goethe was still there with the baton like a conductor when he rehearsed his “Iphigenia”, placing much more value on the correct speaking of the iambs and so on than on the literal content. These things are lost on us today.

In eurythmy, one seeks precisely this plastic and musical element behind the spoken word and thereby arrives precisely at the artistic element, thus going back, as it were, to the source of artistic creation, seeking particularly not into the abstract, into the abstract, watered-down, tonal, but seeks to enter into the rhythmic-tactile, into a way of speaking that we find more and more the more we penetrate to the original epochs of any language.

There is, of course, a great deal to be said about this. I will just add that, on the one hand, our eurythmy performances are accompanied by the musical element or, on the other hand, by the recitation element. And in the art of recitation, in particular, we are in the process – as you will hear – of once again moving away from what is cultivated in the art of recitation in today's unartistic age: the literal, the prosaic content. We are compelled to go back from the prosaic content and the literal to the rhythmic, the one that is actually artistic in poetry. And so it may well be said: there is so little arbitrariness in this eurythmic art that when two people or two groups of people present one and the same thing, the individual expression will not be more different than when a Beethoven sonata or something else is presented by two different performers.

You will see, dear attendees, that even drama can be supported by eurythmy today. You will find lyricism and epic, humor, satire and so on presented; everywhere, excluding pantomime, an attempt is made to recreate the content through artistic expression. Those who have visited us often will see how hard we have worked, especially in the last few months, to anticipate something in the formation of form.

Although we are our own harshest critics and we know that we may not even be at the beginning of an attempt today, but only at the beginning of an attempt, we still think that one day it will be possible - I have not yet been able to do so, but it is something we should work on. We should also be able to conquer the dramatic in an artistic eurythmic way, so that the dramatic forms themselves can one day be transformed into eurythmic forms. Until now, we have only tried to help the dramatic through the eurythmic in our recurring rehearsals of scenes from Goethe's “Faust” by depicting them in eurythmy. We do this wherever Goethe – as he does so often in his “Faust” and in his other poems, wherever he points to the supersensible in what takes place only in the physical realm — where he presents these scenes, which shows us the connection between the human soul and the supersensible, as is the case with this first scene from the second part of 'Faust', in which Goethe has indeed been attacked so often.

It would be interesting if I could explain – but there is not enough time – how much this particular scene from “Faust” has been misunderstood. It is indeed difficult to understand, when Faust – and this is the result of the first part – is standing there with the most severe pangs of conscience, apparently laden, with terrible guilt on his soul, he is supposed to live life, he is supposed to strive “to the highest existence forever”. Yes, it is necessary to point out in the most intimate way what can enter the human soul from the spiritual world and heal it. This is what Goethe attempted in this scene, which we want to present here with the help of eurythmy.

Until now, we have always presented the actual scenes taking place in physical life dramatically, as is usually the case. Where the sensual passes over into the supersensual, we must resort to the eurythmic art. We hope that we will eventually succeed in translating the drama, the actual dramatic form into eurythmy. But, as I said, the eurythmic art is still in its infancy, and I would ask you to consider what we have already rehearsed as a beginning. We are, however, convinced that this beginning can be perfected – probably by others, in part we ourselves will still be able to do it – but we are of the essence of this eurythmic art believe that this eurythmic art will one day be able to stand as a full-fledged art alongside the other full-fledged sister arts.

Ansprache zur Eurythmie

Diese Aufführung richtete sich speziell an Besucher der Schweizer Mustermesse in Basel. Im Christlichen Volksboten für Basel (Nr. 23/1920) wurde darüber von Pfarrer H. Nidecker-Roos am 9. Juni 1920 berichtet: «Auf großen Plakaten wurden die Besucher der Mustermesse in Basel eingeladen das seiner Vollendung entgegengehende Heiligtum der Vereinigung der sog. Anthroposophen zu besichtigen und den anschließenden «Eurhythmischen Spielen» beizuwohnen. [...] Vor dem großen Hauptportal gruppierten sich die zirka 300 Besucher um die markante, lebhaft an einen Priester gemahnende Erscheinung Dr. Steiners, der den Bau bis in seine Details nicht nur entworfen, sondern, um mich seiner Ausdrucksweise zu bedienen, «empfunden» hat. Die Erklärung des Bauwerkes war zugleich eine Einführung in die Hauptideen des Anthroposophismus. [...] Nach dieser Erklärung folgten die ‹Eurhythmischen Spiele› (‹eurhythmisch› kann übersetzt werden mit ‹in wohlbelautendem Takt abgemessen›). Der Gedanke derselben ist folgender: Beim Sprechen vollführt der menschliche Kehlkopf gewisse Bewegungen, in denen sich der Wille zeigt, der in der Sprache zum Ausdruck kommt. Diese Bewegungen sollen sich durch eine ernstere Form des Einzel-Tanzes auf den ganzen Körper übertragen, und so soll der ganze Mensch ein einziger Ausdruck des gesprochenen Wortes sein. Etwa dreißig in Weiß gekleidete Töchter mit farbigen Schleiern tanzten so u. a. die von Frau Steiner rezitierte erste Szene des zweiten Teiles von Goethes Faust, ferner verschiedene Gedichte von Goethe, von Morgenstern und von Steiner. Beiverschiedenen Nummern gelang der Versuch wirklich gut. Die Tänze haben durchaus nichts theatermäßiges an sich. Es sind ernste Versuche, Sprach- und Seelenvorgänge zum Ausdruck zu bringen durch die Bewegungen des Körpers. Der Eindruck der Spiele hat etwas Ernstes, durchaus Geistiges.»

Meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden!

Gestatten Sie, dass ich, wie sonst immer vor diesen Proben einer eurythmischen Darstellung, auch heute einige Worte voraussende. Diese einleitenden Worte sollen ja niemals dazu da sein, um etwa in richtigem Sinne zu kommentieren oder zu erklären etwa die eurythmische Kunst; das würde von vornherein unkünstlerisch sein. Denn alles dasjenige, was wirklich künstlerisch ist, muss sich durch sich selbst rechtfertigen vor der Anschauung, vor dem unmittelbaren Eindruck. Doch ist gerade mit der Eurythmie, wie sie hier gepflegt wird, wirklich sowohl hinsichtlich der künstlerischen Quellen, wie auch hinsichtlich der künstlerischen Formensprache etwas Neues versucht, was auch nicht unmittelbar verglichen werden kann mit irgendwelchen benachbarten Künsten, Tanzkünsten und dergleichen. Und deshalb ist es eben notwendig, dass über die Quellen und über die besondere Art der Ausdrucksweise dieses eurythmischen Kunstversuches einiges voraus gesagt wird.

Sie werden sehen, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, auf der Bühne allerlei Bewegungen, die ausgeführt werden von einzelnen Menschen durch ihre Glieder - und zwar absichtlich durch Arme, Hände in der Hauptsache, aber auch mit der anderen körperlichen Gliedlichkeit -, und Sie werden sehen Bewegungen des einzelnen Menschen im Raume, Bewegungen und wechselseitiges Stellungnehmen von Menschengruppen und so weiter. Das alles sind nicht etwa Willkürgebärden, Gebärden, die im Augenblicke gefunden werden aus irgendeiner willkürlichen Phantasie heraus. Zu dem, was da zugrunde liegt in der eurythmischen Darstellung, gehört immer ein Dichterisches oder ein Musikalisches, besonders bei dem, was Ihnen da als Eurythmie entgegentritt, wo man es wirklich zu tun hat mit einer stummen Sprache, mit einer Sprache, die sich nur anderer Mittel bedient als unsere gewöhnliche Lautsprache. Gar nichts Willkürliches kommt in derselben zum Ausdruck.

Ich darf, wenn ich charakterisieren will dasjenige, was hier versucht ist, wirklich von Goetheanismus sprechen, wie auch alles Goetheanismus ist in seiner Fortbildung, was hier mit der Geistesströmung zusammenhängt, die mit diesem Bau wieder erneuert wird. Denn ich brauche nur zu erinnern an das Wort, das Goethe öfter gebraucht hat und das gerade in dieser Art der künstlerischen Natur, die der Eurythmie zugrunde liegt, besonders bezeichnend ist, ich möchte erinnern an das Wort Goethes vom sinnlich-übersinnlichen Schauen. Sinnlich-übersinnliches Schauen ist es, durch das gewonnen werden die Bewegungsformen der stummen Sprache der Eurythmie.

Sie wissen ja, dass wir im gewöhnlichen Leben, auch im Genießen des Dichterischen oder Gesanglichen, unsere Aufmerksamkeit dem Tone und dem Lautlichen zuwenden, der Sprache oder des Gesanges, und dass wir naturgemäß keine Anschauung haben von den Bewegungen, welche der Kehlkopf und die anderen Sprachorgane ausführen, indem eben die Sprache zustande kommt. Nun handelt es sich zunächst darum, dass man ja allerdings durch sinnlich-übersinnliches Schauen auch deutliche Bilder von dem bekommen kann, was sich abspielt als Bewegung, während wir unsere Aufmerksamkeit dem Laute, dem Tönenden zuwenden. Aber das ist es zunächst nicht, was unmittelbar der Eurythmie zugrunde liegt, sondern in all diesen Bewegungen, die ja kleine Vibrationsbewegungen sind, die sich nicht durch die besondere Einrichtung des Kehlkopfes und der anderen Sprachorgane auf die Luft übertragen, all diesen kleinen Vibrationsbewegungen liegen zugrunde Bewegungstendenzen, und diese Bewegungstendenzen können angeschaut werden. Diese Tendenzen, die also durchaus nicht willkürlich sind, sondern gesetzmäßig verbunden sind mit unserem Organismus, indem dieser ein Sprachorganismus ist, diese gesetzmäßigen Bewegungen lassen sich übertragen von dem lokalisierten Sprachorgan auf den ganzen Menschen.

Das goethesche Prinzip der Metamorphose - es ist ja wirklich, trotzdem sich einzelne Denker schon im Laufe des 19. Jahrhunderts damit beschäftigt haben, hinter die ganze Tiefe dieses Metamorphosegedankens zu kommen, noch durchaus nicht in hinlänglicher Weise unserem Geistesleben einverleibt. Denn man wird sehen, während man es mehr oder weniger heute noch als ein formalistisches Prinzip annimmt, man wird sehen, wie durch eine richtige Belebung des Metamorphoseprinzips das Verständnis des Lebendigen sich eröffnet und wie man dann kann unmittelbar ins Künstlerische übertragen dasjenige, was dem Metamorphoseprinzip zugrunde liegt, wie Goethe es wirklich nicht als ein bloßes Bild, sondern als eine tiefes Naturgestaltungsprinzip aussprach, dass die ganze Pflanze ein kompliziertes Blatt darstelle, dass jede Pflanze eine umgewandelte, eine metamorphosierte Form der anderen Form, der Blattform ist.

Diese Formen ins Künstlerische umgesetzt, zeigt, dass der ganze Mensch Bewegungen ausführt, die sonst als Bewegungstendenzen im einzelnen Organ des Kehlkopfs und seiner Nachbarorgane sind; gewissermaßen dasjenige, was Sie auf der Bühne sehen, würde der ganze Mensch sein als bewegter Kehlkopf, möchte ich sagen. Nichts Willkürliches, nichts Pantomimisches, nichts Mimisches - so wenig die Sprache selbst mimisch oder pantomimisch ist. Natürlich, im Einzelnen geht sie in das eine oder andere über; aber so wenig sie im Ganzen mimisch oder pantomimisch ist, so wenig ist dasjenige, das hier als Eurythmie sich darbietet, etwas Pantomimisches oder Mimisches oder besteht in Zufallsgesten. So, wie das Musikalische selbst in seinem melodiösen Elemente eine gesetzmäßige Aufeinanderfolge von Tönen und Tonbildern ist, so besteht hier alles in der gesetzmäßigen Aufeinanderfolge der Bewegungen.

Man muss allerdings ein wenig hineinschauen in die ganze, ich möchte sagen künstlerische Strebensunruhe der Gegenwart, in das merkwürdige künstlerische Suchen, wenn man berechtigt finden will dasjenige, das gerade mit dieser Eurythmie angestrebt wird. Es wird zurückgegangen in gewissem Sinne zu den ursprünglichsten Quellen künstlerischen Gestaltens, indem der Mensch selber - aber der ganze Mensch - aufgerufen wird als ein künstlerisches Ausdrucksmittel, wirklich künstlerisches Ausdrucksmittel. Der Mensch selbst wird zum künstlerischen Werkzeug, und die in ihm liegenden Bewegungsmöglichkeiten, sie werden zur künstlerischen Formensprache.

Heute sucht man ja, weil vieles Künstlerische ins Konventionelle übergegangen ist, zu den ursprünglichen, elementaren künstlerischen Quellen wiederum zurückzugehen. Im Dichterischen ist ja die Neigung - sehr, sehr vieles [ist] eigentlich heute schon recht spürbar (?), und gerade die zivilisierten Sprachen müssen das sprachliche Element immer mehr und mehr überführen ins Prosaische, wir brauchen als Verkehrssprache das Konventionelle der Sprache, wir brauchen unsere sonstigen Erkenntnisse und so weiter -, [es ist die Neigung da,] die Formen unserer Technik zum Ausdruck zu bringen. Wir brauchen das Gedankliche, das Ideenmäßige in der Sprache - gerade, indem die Sprache sich weiterentwickelt, wird sie immer mehr und mehr zum Träger der Ideen, Gedanken, Vorstellungen, und dadurch entfernt sie sich von dem Künstlerischen. Denn der Tod alles Künstlerischen ist das Ideelle, das Gedankliche. Das Künstlerische muss unmittelbar - zwar als ein Tiefes, aber nicht als ein Gedankliches - empfunden werden aus dem Bilde heraus in der menschlichen Sprache. Indem sie aus dem Kehlkopfe dringt, da vereinigt sich aus der menschlichen Wesenheit heraus das Gedankenelement und das Willenselement, das aber jetzt aus dem ganzen Menschen, wenn ich mich jetzt des trivialen, aber doch treffenden, Ausdrucks bedienen darf, schießt, eben dasjenige, was der Kehlkopf vollbringt, sich dort vereinigt als Willenselement mit dem Gedanklichen.

Indem wir nun zur Eurythmie übergehen, lassen wir das gedankliche Element, auch der Dichtung, nur Begleiter sein. Und in dem, was auf der Bühne dargeboten wird, kommt bloß in den Bewegungen des Menschen und der Menschengruppen das Willenselement heraus. Der ganze Mensch geht in die Bewegung über. Wer ein gewisses Gefühl hat dafür, wie in der Sprache sich unsere Individualität bilden muss — ich möchte sagen, sie ist etwas starr Werdendes. Wir fühlen ja alle, indem wir sprechen, wenn wir ein Gefühl dafür haben, wir fühlen ja alle, wenn wir sprechen, dass wir uns in cine Sprache hineinsprechen müssen, die nicht bloß aus unserer Individualität kommt. Das, was individuell aus uns entspringt, das muss sich fortbewegen auf den Wellen der Volkssprache und so weiter. Das empfindet man. Man empfindet, wie das Individuelle nicht hinein will immer. Und wer das nicht empfindet, der ist eben kein ganzer Mensch, jedenfalls keine künstlerische Natur; denn die künstlerische Natur, die will das Individuelle gestalten.

Wir halten gewissermaßen, indem wir eurythmisch dasjenige, was künstlerisch darzustellen ist, wiedergeben, wir halten dasjenige, was da lebt im Menschen, früher an, als es die Lautsprache anhalten kann. Indem zum Beispiel Schiller gerade bei den bedeutsamsten seiner Gedichte immer zuerst eine Melodie im Sinne hatte - oder eine unbestimmte, nebulöse Melodienfolge - und dann erst das Wortwörtliche daran machte, zeigte er, wie er das Musikalische, das doch eigentlich das Künstlerische der Sprache ist, empfand. Oder aber man kann sagen: Das Plastische, das hinter dem Sprechen liegt, das ist wiederum das Künstlerische.

Heute legt man einen großen Wert eigentlich bei einem unkünstlerischen Zeitalter auf das Wortwörtliche, auch der Dichtung. In der Zeit der deutschen Romantik haben sich die Leute zusammengesetzt, und namentlich gern auch Gedichte gehört, die ganz bestimmt gestaltete Strophen in Sprachen [hatten], die sie nicht verstanden haben ‚oder die sie wenigstens schwer verstanden haben, weil man dazumal in einem mehr künstlerischen Zeitalter mehr Empfindung hatte für den Rhythmus, Takt, für alles dasjenige, was das eigentlich Künstlerische in der Sprache ist. Und Goethe stand noch mit dem Taktstock wie ein Kapellmeister da, wenn er seine «Iphigenie» einstudierte, viel mehr als auf den wortwörtlichen Inhalt, auf das richtige Sprechen der Jamben und so weiter Wert legend. Diese Dinge kommen uns heute abhanden.

In der Eurythmie sucht man gerade dieses hinter dem gesprochenen Worte stehende plastische und musikalische Element auf und kommt dadurch gerade auf das künstlerische Element, geht also zurück gewissermaßen wieder zu dem Quell des künstlerischen Schaffens, sucht besonders nicht ins Abstrakte, ins verwässerte, abgetönte Lautliche, sondern sucht hineinzukommen in das Rhythmisch-Taktmäßige, in ein solches Sprechen, wie wir es immer mehr und mehr finden, je mehr wir zu den ursprünglichen Epochen irgendeiner Sprache vordringen.

Darüber wäre natürlich sehr viel zu sagen. Ich will nur noch hinzufügen, dass ja auf der einen Seite entweder unsere eurythmischen Darbietungen begleitet werden von dem musikalischen Elemente oder auf der anderen Seite von dem Rezitationselemente. Und gerade in der Rezitationskunst sind wir dabei - wie Sie hören werden -, wiederum genötigt, abzugehen von dem, was heute eben in einem unkünstlerischen Zeitalter als das Hauptsächlichste in der Rezitationskunst gepflegt wird: das Wortwörtliche, der prosaische Inhalt. Wir sind genötigt, von dem prosaischen Inhalt und dem Wortwörtlichen zurückzugehen zu dem Taktmäßigen, Rhythmischen, demjenigen, was das eigentlich Künstlerische in der Dichtung ist. Und so darf wohl gesagt werden: Dieser eurythmischen Kunst entspricht so wenig Willkürliches, dass, wenn zwei Menschen oder zwei Menschengruppen ein und dieselbe Sache darstellen, so wird die individuelle Ausgestaltung nicht verschiedener sein, als wenn eine Beethovensonate oder etwas anderes von zwei verschiedenen Darstellern dargeboten wird.

Sie werden sehen, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, dass man auch das Dramatische heute schon unterstützen kann durch die Eurythmie. Lyrisches und Episches, Humoristisches, Satirisches und so weiter werden Sie dargestellt finden; überall durchaus unter Ausschluss des Pantomimischen wird versucht, den Inhalt nachzubilden durch dasjenige, was in der künstlerischen Gestaltung liegt. Diejenigen, die uns öfter besucht haben, werden sehen, wie sehr wir daran gearbeitet haben, gerade im Laufe der letzten Monate, in der Formbildung etwas vorzugreifen.

Obwohl wir selbst die strengsten Kritiker sind und ganz gut wissen, dass wir vielleicht heute noch nicht einmal vor einem Versuche, sondern nur vor dem Anfang eines Versuches stehen, denken wir aber doch, dass es auch einmal gelingen wird - was mir bis jetzt durchaus nicht gelingen wollte, aber woran gearbeitet werden soll -, dass auch das Dramatische eurythmisch-künstlerisch bezwungen werden kann, sodass die dramatischen Formen selber ins Eurythmische einmal übergeführt werden können. Bis jetzt haben wir nur durch unsere immer wiederkehrenden Proben von Szenen aus Goethes «Faust» versucht, dem Dramatischen durch das Eurythmische zu Hilfe zu kommen in der Darstellung, indem wir überall da, wo Goethe - wie er es ja zahlreich für seinen «Faust» und in seinen übrigen Dichtungen tut, wo er das bloß im Physischen sich abspielende Menschliche ins Übersinnliche hinaufweist —, wo er darstellt diese Szenen, was uns abbildet den Zusammenhang der menschlichen Seele mit dem Übersinnlichen, wie es bei dieser ersten Szene aus dem zweiten Teil des «Faust» ist, in welcher Goethe ja so vielfach angegriffen worden ist.

Es würde interessant sein, wenn ich erzählen könnte - aber dazu reicht die Zeit nicht aus -, wie sehr man gerade diese Szene aus dem «Faust» missverstanden hat. Sie ist ja auch schwer zu verstehen, wenn Faust — das ist das Ergebnis des ersten Teiles - dasteht mit schwersten Gewissensbissen, offenbar beladen, [er hat] furchtbare Schuld auf die Seele geladen, er soll das Leben weiterleben, er soll «zum höchsten Dasein immerfort» streben. Ja, da ist es nötig, dass in intimster Weise hingedeutet wird auf dasjenige, was heilend in die menschliche Seele hereinziehen kann aus der geistigen Welt. Das versuchte Goethe in dieser Szene, die wir hier mit Hilfe der eurythmischen Kunst darstellen wollen.

Bis jetzt haben wir immer so dargestellt, dass wir die eigentlichen, im physischen Leben verlaufenden Szenen dramatisch geben, wie sonst es gewöhnlich geschieht. Wo das Sinnliche ins Übersinnliche übergeht, muss man zur eurythmischen Kunst greifen. Hoffentlich wird es uns eben schon noch gelingen, das Dramatische, die eigentlich dramatische Form ins Eurythmische zu übersetzen. Aber, wie gesagt, die eurythmische Kunst ist noch im Anfange, und ich bitte auch heute wiederum durchaus, dasjenige, was wir Ihnen schon darbieten können an Proben, als einen solchen Anfang zu betrachten. Wir sind aber der Überzeugung, dass dieser Anfang vervollkommnet werden kann - wahrscheinlich durch andere, teilweise werden wir es ja selbst noch leisten können -, aber wir sind aus dem Wesen dieser eurythmischen Kunst heraus des Glaubens, dass sich diese eurythmische Kunst einstmals als vollwertige Kunst neben die anderen vollwertigen Schwesterkünste wird hinstellen können.