The Origin and Development of Eurythmy

1918–1920

GA 277b

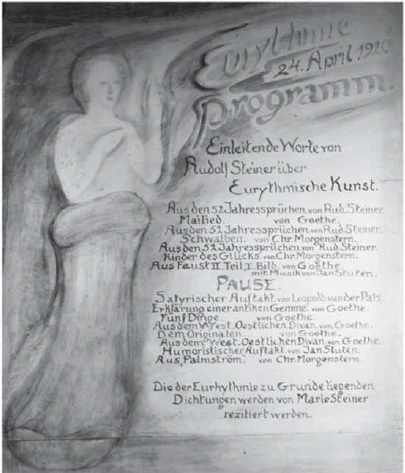

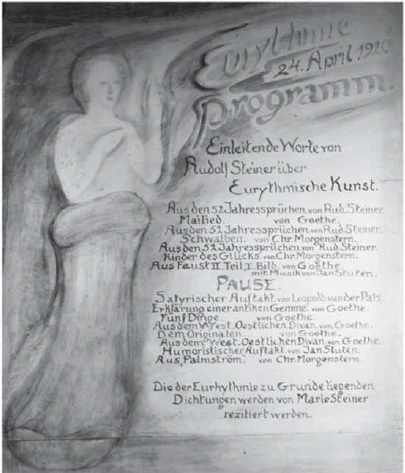

24 April 1920, Dornach

Translated by Steiner Online Library

61. Eurythmy Performance

Dear Ladies and Gentlemen.

As usual before these eurythmy performances, allow me to say a few words today as well, not to explain the performances, because explanations as such are unartistic additions to art, and an art that would require an explanation would be something inartistic. But it is necessary to say a few words about the sources and the particular forms of expression of our eurythmic art. For it is not a matter of a modification of some other art of movement, but rather of an art of movement that, as it happens here, uses the human being as such as an artistic tool for the first time. You will see people in motion on the stage, human limbs in motion, groups of people in motion in such a way that the individual people belonging to them perform movements in relation to one another, that the whole group performs formal movements, and so on.

Now it is certainly true that in everyday life, too, people accompany their speech with some kind of gestures. We will not be dealing with such gestures here, although everything you will see on stage is a silent language, a language that reveals itself through moving sculpture.

That we are dealing with a language is clear from the fact that on the one hand we will hear what is happening on stage accompanied by the poetic text, which is also to be revealed through the silent language of eurythmy. Or that we will also bring musical elements to the stage at the same time, both musically ourselves and through the moving music that eurythmy also is. But these are not random gestures. It is much more than just looking for gestures that can be invented in the moment to accompany the poetic or musical expression. We are not dealing with a gestural art of this kind, but with a real language that simply uses different means of expression than spoken language. That artistic expression can be conveyed through such a silent language, which uses the human being and his movements as a tool, can be seen from the following.

When we speak – whether we speak to communicate as human beings or to express something poetic through language – we always stand before something that is fundamentally foreign to us as individuals. We share language with an entire human community, and if we have an artistic feeling about speaking, it may be expressed in the following way. One may say: the one who feels the full human individuality – and it is this that should actually be expressed in the artistic work – the one who feels the full human individuality, feels the surrender of human will and human feeling to language , to the air connection, to people, as a self-expression of the human, I would even say: as a surrender of our will, which is in a state of perpetual liveliness, to something that has become rigid, that has become a feast.

Therefore, what is poetically and artistically not the literal prose content of a poem. Great poets in particular have felt this. And it must be pointed out again and again how Schiller - especially in the most significant of his poems - felt a kind of indeterminate melody sequence, melody image in his soul and only then attached the literal content to this melody image. Only unartistically sensitive people see the literal content, that is, the prose content of a poem, as the most important thing, but [it lies] in what actually lies behind this literal content, which is given its legitimacy by the phonetic language. So that we can say: the actual artistry in poetry is the rhythm, the beat, the whole form, how thinking, feeling, sensing follow one another, how one thought connects to another. It is not the content of the one thought that matters, but the intertwining of the thoughts. What is actually at the basis of poetry in the prose content is something that is mysteriously worked out of the human will into what is otherwise more strongly influenced by the intellect, by ideas, as is the case with ordinary speech.

The element of artlessness in any art is always constituted by whatever ideas it contains. And precisely because eurythmy can bring out the conceptual, intellectual element and bring the whole human being into speech in his or her revelation, eurythmic speech becomes an artistic language in the most eminent sense, an artistic form of expression. One would like to say: anyone who can feel properly will find in a eurythmic movement, in a eurythmic form, something that is more closely bound to the individual human being than the word, than the sentence. So that one goes back to the human-individual by going from speech to eurythmy.

And there is nothing arbitrary about it. Rather, it is precisely that which is studied in phonology that is usually ignored when listening to phonology. The sequence of sounds, the content of the words, everything that is suppressed in eurythmy is observed. Because it is suppressed, we still have to accompany eurythmy with poetry or music today. But something else comes into it. The person who does eurythmy will find that when he makes a eurythmic movement, he lives into it with his whole being, whereas in phonetic speech he gives himself to a single human organ. That is precisely what this larynx and its neighboring organs develop in terms of movement tendencies when speaking. And this is transmitted to the movements of the whole person in accordance with the law.

So that on the stage you see something like moving larynxes in the whole person or in the group of people. If you could graphically capture the movements of the larynx, palate, tongue and lips through some instrument and could detach the tremulous movements from the lines that pass through them as movement tendencies, you would see everywhere the movements that you have made here on the stage by the person. So that when groups or two individuals in different places perform the same piece of music eurythmically, there is no more difference than when two pianists play the same sonata. Just as music consists in the lawful succession of melodies, so here this moving music consists in the lawful succession of movements that are eavesdropped from the movement tendencies of the human speech organs. One can do this through this supersensible seeing because through this seeing one brings to expression precisely that which can be expressed in human speech, which is otherwise not observed.

So, if you have a true sense of eurythmy, you can say: what is it? It is what would arise if one could suddenly enlarge the movements of the larynx, the palate, the lips, so that they would take up the size of the whole human being, and then let the whole human being carry out what has been enlarged. So it is based on a real observation of what the soul pours into the sound. Here in eurythmy, the soul pours this into the movements.

Therefore, when reciting and declaiming eurythmy, one must fall back on the good old forms of reciting and declaiming, so that what today's unartistic times as the main thing, where one says that he recites well who inwardly emphasizes the feeling that lies in the word, but who actually only looks at the prose content of the poetry and only reproduces the prose content of a poem in this way. Rather, one must be mindful of what real artists meant, for example, Goethe, when he himself rehearsed his dramas with the individual actors with a baton like a conductor, in order to orient his actors' speech towards the iambic foot. We must go back to the rhythm, the beat, the formal, formal side of what is truly artistic and forms the basis of poetry. Otherwise we would not be able to cope with recitation, which should go hand in hand with eurythmy. — Musical accompaniment should also accompany our eurythmy.

In the first part of the performance, before the break, you will see in particular the very significant scene from the beginning of the second part of Goethe's “Faust”. And it shows how eurythmy can be used to depict on stage what otherwise cannot be done with ordinary naturalism. Anyone who has seen many Faust performances in a wide variety of adaptations knows how difficult it is to present on stage, especially in Goethe's Faust, that which leads away from the ordinary prose content of life and presents the relationship of the human soul to the supersensible world. We gave that in particular in this first scene of the second part. People have even reproached Goethe for the fact that, after Faust has taken upon himself the great, heavy guilt of murder and is tormented by terrible pangs of conscience, he is brought into a situation like the one at the beginning of the second part. There appear those powers that operate in the supersensible realm and influence the human soul. When they are dramatically presented, they must, of course, be personified. However, they are meant as an illustration of the real supersensible world.

For example, a certain Mr. Max Rieger, who wrote a little book about Goethe's “Faust”, claimed that Goethe was of the opinion that if a person has incurred a serious debt, all he needs to do is take a morning walk in the fresh sunlight and he will be cured of these pangs of conscience. This is certainly not what Goethe meant here. Rather, it means that the metamorphosis of the soul, after the soul has taken on such burdens as Faust, can only take place through an influence from the supersensible world.

Now it has been shown that such supersensible scenes can be properly presented on stage with the help of eurythmy. I am very busy trying to develop dramatic works further. Today we prefer to present lyric, epic and similar works because these are the only ones we can do. But I am also trying to find forms that can be used to express and present drama as such, in eurythmy. But even without this having been achieved, to present the drama in the course of dramatic action, the tensions and solutions in eurythmy: If we retain the usual theatrical art and technique for what takes place in physical life, eurythmy can be called upon to help where dramatic poetry rises from physical experience to supra-physical experience, to spiritual experience in something like the case of this scene.

I have indicated how I hope that the Eurythmic Art can also be extended to the dramatic, to the generally dramatic – I hope this. Those who have been here often as honored listeners will see that we have endeavored, especially in the last few months, to arrive at ever more perfections in this eurythmic art. Nevertheless, there is still a great deal to be done. And so I must ask the esteemed audience for their forbearance today, because we are just beginning with our eurythmic art. But we believe that, since it makes use of the means of human movement itself as a tool and draws from the very original sources of artistic creation from the depths of the human soul and is seeking new forms for it, [then] this eurythmic art will one day be able to present itself as a fully-fledged art in the world alongside the older arts that have already earned their place in the world.

As I said, it should be noted that we are still dealing with a beginning, perhaps even with the attempt at a beginning in the emerging eurythmic art, which – perhaps no longer through us, but probably through others – will be able to develop into a fully-fledged, younger art.

We will also present Goethean humor today. You will see just from the presentation of Goethean humor through eurythmy how unique this Goethean humor is: a humor that can rise to the heights of world-view contemplation and yet remains an elementary, healthy humor.

I would like to point out, if you will allow me, dear assembled colleagues, that we are now making a special effort to show, in the eurythmy we perform for such humorous poems, how the main value in this eurythmizing does not lie, as I said, in the expression of the prose content in the forms or gestures, but in what the poet has done artistically. So that one can indeed feel the artistic shaping of language again, also in the moving, the mute language of eurythmy.

So it should be clear that I am not trying to recreate the humoristic content of the Humoresken through mimicry or pantomime, but rather to show how the artistic sound form is transformed into eurythmic, silent forms of movement.

But that is only a beginning – with the lyrical part or the dramatic part of the scenes that lead into the supersensible. On the other hand, it will be my task for the future to enrich the drama itself, the dramatic presentation through eurythmy in a certain way. This must, of course, be quite different from what you can already offer today. What we can offer now may be received with leniency – we are our own harshest critics. But we also know that there are possibilities for developing this eurythmy into a complete work of art, either through us, if our contemporaries show enough interest, or through others.

Ansprache zur Eurythmie

Meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden!

Gestatten Sie, dass ich auch heute, wie sonst vor diesen eurythmischen Aufführungen, einige Worte voraussende, nicht um etwa die Darbietungen zu erklären, denn Erklärungen sind als solche Künstlerischem gegenüber unkünstlerische Beigaben, und eine Kunst, die erst einer Erklärung bedürfte, wäre ja eben auch etwas Unkünstlerisches. Aber es ist notwendig, über die Quellen und die besonderen Ausdrucksformen unserer eurythmischen Kunst doch einige Worte zu sagen. Denn es handelt sich nicht um eine Modifikation irgendwelcher anderer Bewegungskünste, sondern es handelt sich um eine Bewegungskunst, die so, wie es hier geschieht, zum ersten Mal den Menschen als solchen verwendet als künstlerisches Werkzeug. Sie werden auf der Bühne Menschen in Bewegung sehen, menschliche Glieder, bewegt, Menschengruppen so bewegt, dass die einzelnen ihnen zugehörigen Menschen gegenseitig Bewegungen ausführen, dass die ganze Gruppe Formbewegungen ausführt und so weiter.

Nun ist es ja gewiss wahr, dass der Mensch auch im gewöhnlichen Leben durch irgendwelche Gebärden seine Sprache begleitet. Um solche Gebärden wird es sich hier nicht handeln, trotzdem alles dasjenige, was Sie auf der Bühne sehen werden, eine stumme Sprache ist, eine Sprache, die gleichsam durch eine bewegte Plastik sich zur Offenbarung bringt.

Dass wir es mit einer Sprache zu tun haben, das geht ja schon daraus hervor, dass wir auf der einen Seite begleitet hören werden das, was auf der Bühne zu sehen ist, von dem dichterischen Text begleitet, der auch durch die stumme Sprache der Eurythmie sich offenbaren soll. Oder dass wir auch Musikalisches zu gleicher Zeit eben musikalisch selbst und durch diese bewegte Musik, welche die Eurythmie auch ist, werden zur Darstellung bringen. Aber es handelt sich eben durchaus nicht um irgendwelche Zufallsgebärden. Es handelt sich vielmehr durchaus nicht um das Aufsuchen von Gebärden, die etwa im Augenblicke zu dem dichterischen Ausdruck oder zu dem musikalischen Ausdruck hinzuerfunden werden. Wir haben es nämlich nicht mit einer solchen Gebärdenkunst zu tun, sondern mit einer wirklichen Sprache, die sich nur anderer Ausdrucksmittel bedient als die Lautsprache. Dass durch eine solche stumme Sprache, die sich des Menschen selbst und seiner Bewegungen als Werkzeug bedient, gerade Künstlerisches zum Ausdrucke kommen kann, das mögen sie aus Folgendem ersehen.

Wenn wir sprechen - sei es, dass wir sprechen, um uns als Menschen zu verständigen, sei es, dass wir Dichterisches durch die Sprache zum Ausdrucke bringen -, so stehen wir immer gegenüber etwas im Grunde als individuelle Menschen Fremdem. Die Sprache haben wir mit einer ganzen Menschengemeinschaft eben gemein, und wenn wir eine künstlerische Empfindung gegenüber dem Sprechen haben, so darf diese vielleicht in der folgenden Weise zum Ausdruck kommen. Man darf sagen: Derjenige, der die volle Menschenindividualität - und die ist es ja, die eigentlich im künstlerischen Werke zum Ausdruck kommen soll -, wer die volle Menschenindividualität empfindet, der empfindet das Hingeben des menschlichen Wollens und des menschlichen Fühlens an die Sprache, an die Luftverbindung, an die Menschen, wie ein Sich-Entäußern des Menschlichen, ich möchte sagen: wie ein Hingeben unseres in fortwährender Lebendigkeit befindlichen Willens an etwas Erstarrtes, ein Festgewordenes.

Daher ist auch nicht dasjenige dichterisch-künstlerisch, was der wortwörtliche Prosainhalt einer Dichtung ist. Gerade große Dichter haben das gefühlt. Und man muss immer wieder hinweisen darauf, wie Schiller - gerade bei den bedeutsamsten seiner Gedichte - eine Art unbestimmter Melodiefolge, Melodiebild in seiner Seele fühlte und an dieses Melodiebild erst den wortwörtlichen Inhalt heranbrachte. Nur unkünstlerisch empfindende Menschen sehen in dem wortwörtlichen Inhalt, also in dem Prosagehalt eines Gedichtes, dasjenige, worauf es ankommt, sondern [er liegt] in dem, was eigentlich erst hinter diesem wortwörtlichen Inhalt, der seine Gesetzmäßigkeit durch die Lautsprache erhält, liegt. Sodass wir sagen können: Das eigentlich Künstlerische in der Dichtung ist der Rhythmus, der Takt, die ganze Form, wie aufeinanderfolgen Denken, Fühlen, Empfinden, wie ein Gedanke sich mit dem andern verbindet. Es kommt nicht auf den Inhalt des einen Gedankens an, sondern auf die Verschlingung der Gedanken. Das, was da eigentlich in dem Prosagehalt der Dichtung als das eigentlich Künstlerische zugrunde liegt, das ist etwas, was aus dem menschlichen Willen hineingeheimnisst wird in das, was sonst stärker beeinflusst ist von dem Intellekt, von den Ideen, wie es beim gewöhnlichen Sprechen der Fall ist.

Dasjenige, was irgendeine Kunst an Ideen enthält, macht eigentlich immer das unkünstlerische Element aus. Und indem wir gerade durch die Eurythmie herausbringen können das ideelle, das intellcktuelle Element und hineinbringen können in die Sprache den ganzen Menschen in seiner Offenbarung, wird die eurythmische Sprache eine im eminentesten Sinne künstlerische Sprache, eine künstlerische Ausdrucksform. Man möchte sagen: Wer richtig empfinden kann, wird in einer eurythmischen Bewegung, in einer eurythmischen Form etwas finden, was vielmehr an den individuellen Menschen gebunden ist als das Wort, als der Satz. Sodass man wieder zurückgeht in das Menschlich-Individuelle, indem man von der Lautsprache zur Eurythmie schreitet.

Und nichts Willkürliches ist drinnen, sondern es ist eben gerade das an der Lautsprache studiert, was man sonst nicht beachtet, wenn man der Lautsprache zuhört. Man beachtet die Tonfolge, den Inhalt der Worte, alles dasjenige, was in der Eurythmie unterdrückt wird. Weil es unterdrückt wird, müssen wir ja eben heute noch diese Eurythmie begleiten lassen von der Dichtung oder von der Musik. Aber dafür tritt etwas anderes ein. Der Mensch, der selber eurythmisiert, wird finden: Indem er eine eurythmische Bewegung macht, lebt er sich in diese mit seinem ganzen Menschen hinein, während er sich bei der Lautsprache hingibt an ein einzelnes menschliches Organ. Das ist eben studiert, was dieser Kehlkopf und seine Nachbarorgane an Bewegungstendenzen beim Lautsprechen entwickeln. Und das ist gesetzmäßig übertragen an die Bewegungen des ganzen Menschen.

Sodass Sie auf der Bühne sehen im ganzen Menschen oder in der Menschengruppe etwas wie bewegte Kehlköpfe. Sie würden einfach, wenn Sie könnten durch irgendein Instrument, die Bewegungsformen des Kehlkopfes, des Gaumens, der Zunge, der Lippen grafisch festhalten und würden loslösen können aus den Zitterbewegungen Linien, die durch die Zitterbewegungen als Bewegungstendenzen durchgehen, so würden Sie überall sehen die Bewegungen, die Sie hier von dem Menschen gemacht haben, sehen auf der Bühne. Sodass, wenn Menschengruppen oder zwei Menschen an verschiedenen Orten ein und dasselbe Musikstück eurythmisch darstellen, nicht mehr Unterschied darinnen ist, wie wenn zwei verschiedene Klavierspieler ein und dieselbe Sonate zu spielen haben. Wie die Musik in der gesetzmäßigen Aufeinanderfolge der Melodien besteht, so hier diese bewegte Musik in der gesetzmäßigen Aufeinanderfolge der Bewegungen, die abgelauscht sind den Bewegungstendenzen der menschlichen Sprachorgane. Man kann das durch dieses übersinnliche Schauen, weil man durch dieses Schauen gerade das Ausdrückbare am menschlichen Sprechen, was sonst nicht beachtet wird, zur Darstellung bringt.

So kann man sagen, wenn man Eurythmie richtig empfindet: Was ist sie denn? Sie ist das, was entstehen würde, wenn man die Bewegungsvorgänge des Kehlkopfes, des Gaumens, der Lippen, plötzlich vergrößern könnte so, dass sie die Größe des ganzen Menschen einnehmen würden, und dann vom ganzen Menschen das ausführen lassen würde, was so vergrößert ist. - Also es beruht auf einem wirklichen Beobachten desjenigen, was die Seele in den Laut gießt. Hier in der Eurythmie gießt die Seele das in die Bewegungen hinein.

Daher muss man, indem die Eurythmie rezitatorisch und deklamatorisch begleitet wird, wiederum zu den guten, alten Formen des Rezitierens und des Deklamierens zurückgreifen, damit nicht das zur Hauptsache gemacht wird, was die heutige unkünstlerische Zeit als die Hauptsache ansieht, wo man sagt, der rezitiere gut, der, der betone recht innerlich das Gefühl, das auf dem Worte liegt, der aber eigentlich nur auf den Prosagehalt der Dichtung sieht, nur den Prosagehalt eines Gedichtes in dieser Weise wiedergibt. Sondern man muss eingedenk sein desjenigen, was wirkliche Künstler gemeint haben, zum Beispiel Goethe, wenn er mit dem Taktstock wie ein Kapellmeister selbst seine Dramen mit den einzelnen Schauspielern einstudierte, um auf den jambischen Versfuß hin die Sprache seiner Schauspieler zu orientieren. Man muss wiederum zurückgehen zum Rhythmus, zum Takt, zur formellen, formalen Seite, desjenigen, was als wirklich Künstlerisches der Dichtung zugrunde liegt. Sonst würde man mit dem Rezitieren, das einhergehen soll neben der Eurythmie, nicht zurechtkommen. — Auch Musikalisches soll begleiten unsere Eurythmie.

Sie werden im ersten Teil der Vorführungen vor der Pause insbesondere sehen die sehr bedeutende Szene des Anfanges des zweiten Teils des «Faust» von Goethe. Und da zeigt sich, wie man gerade die Eurythmie verwenden kann, um dasjenige darzustellen, bühnenmäRig gerade zu machen, was sonst mit dem gewöhnlichen Naturalismus durchaus nicht bühnenmäßig gemacht werden kann. Wer viele «Faust»-Darbietungen in verschiedensten Bearbeitungen gesehen hat, der weiß, wie schwer gerade bei Goethe’schem «Faust» dasjenige auf der Bühne darzustellen ist, was von dem gewöhnlichen Prosagehalt des Lebens abführt und die Beziehungen der menschlichen Seele zur übersinnlichen Welt darstellt. Die haben wir in dieser ersten Szene des zweiten Teils ganz besonders gegeben. Man hat Goethe sogar den Vorwurf darüber gemacht, dass er, nachdem Faust die große, schwere Schuld des Mordes sogar auf sich geladen hat, von furchtbaren Gewissensbissen gequält ist, in eine solche Lage gebracht wird, wie im Beginne des zweiten Teils. Da treten ja diejenigen Mächte auf, die aus dem Übersinnlichen herein in die Menschenseele wirken, die natürlich, wenn sie dramatisch vorgeführt werden, personifiziert werden müssen, aber nicht als Personifikation gemeint sind, sondern als Anschauung der wirklichen übersinnlichen Welt.

Es hat zum Beispiel ein Herr Max Rieger, der ein Büchelchen geschrieben hat über den Goethe’schen «Faust», gemeint, Goethe wäre der Ansicht gewesen: wenn ein Mensch eine schwere Schuld auf sich geladen hat, so brauche er nur einen Morgenspaziergang zu machen im frischen Sonnenlicht, so wird er von diesen Gewissensbissen geheilt sein. So ist es allerdings hier bei Goethe nicht gemeint. Es ist vielmehr das gemeint, dass die Metamorphose der Seele, nachdem die Seele solches auf sich geladen hat wie Faust, nur durch eine Beeinflussung von Seiten der übersinnlichen Welt vor sich gehen könne.

Nun hat sich herausgestellt, dass man gerade durch die Zuhilfenahme der Eurythmie solche übersinnlichen Szenen sachgemäß auf der Bühne darstellen kann. Ich bin ja sehr damit beschäftigt, auch den Versuch zu machen, Dramatisches überhaupt noch weiter auszuarbeiten. Wir stellen ja heute vorzugsweise — weil wir nur das können - Lyrisches, Episches und dergleichen dar; aber ich bin auch schr damit beschäftigt, vielleicht Formen einmal zu finden, durch die ausgedrückt und dargestellt werden kann das Dramatische als solches auch eurythmisch. -— Aber auch ohne, dass das schon erreicht ist heute, das Dramatische im Gang der dramatischen Handlungen, die Spannungen und Lösungen eurythmisch darzustellen: Wenn man beibehält die gewöhnliche bühnenmäßige Kunst, die gewöhnliche Bühnentechnik für das im physischen Leben sich Abspielende, so kann die Eurythmie zu Hilfe gerufen werden da, wo die dramatische Dichtung sich von dem physischen Erleben erhebt zu dem überphysischen Erleben, zu dem geistigen Erleben bei so etwas, wie es bei dieser Szene der Fall ist.

Ich deutete darauf hin, wie ich hoffe, dass die Eurythmische Kunst auch auf das Dramatische, auf das allgemein Dramatische wird ausgedehnt werden können - ich hoffe dieses. Diejenigen, die als verehrte Zuhörer öfter dagewesen sind, werden ja sehen, dass wir uns bemüht haben, namentlich in den letzten Monaten zu immer Vollkommenerem und Vollkommenerem gerade in dieser eurythmischen Kunst zu kommen. Dennoch aber ist noch sehr vieles zu tun. Und ich darf daher auch heute die verehrten Zuhörer um Nachsicht bitten, denn wir stehen mit unserer eurythmischen Kunst am Anfange. Aber wir glauben, dass sie, da sie sich des Mittels des menschlichen Bewegens selbst bedient als eines Werkzeuges und da sie schöpft aus den allerursprünglichsten Quellen des künstlerischen Schaffens aus den Tiefen der menschlichen Seele und dafür neue Formen sucht, [dadurch] wird sich diese eurythmische Kunst einmal neben die älteren Künste, die sich schon ihre Stellung in der Welt erworben haben, als vollberechtigte Kunst in der Welt hinstellen können.

Wie gesagt, es ist darauf aufmerksam zu machen, dass wir es noch mit einem Anfange, vielleicht sogar mit dem Versuch eines Anfanges in der werdenden eurythmischen Kunst zu tun haben, die - vielleicht nicht mehr durch uns, aber durch andere wahrscheinlich - zu einer vollwertigen, jüngeren Kunst wird ausgebildet werden können.

Auch Goethe’schen Humor werden wir heute zur Darstellung bringen. Man wird ja gerade an der Darstellung des Goethe’schen Humors durch die Eurythmie sehen, wie eigenartig dieser Goethe’sche Humor ist: Ein Humor, der sich erheben kann bis in die Höhen des Weltanschauungs-Betrachtens und der doch ein elementarisch-gesunder Humor bleibt.

Ich mache Sie darauf aufmerksam, wenn Sie mir das gestatten, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, dass wir uns jetzt besonders bemühen, an solchen humoristischen Dichtungen, die wir in Eurythmie umsetzen, zu zeigen, wie der Hauptwert bei diesem Eurythmisieren nicht darinnen liegt, wie ich schon sagte, dass der Prosainhalt in den Formen oder Gesten zum Ausdrucke kommt, sondern dasjenige, was der Dichter künstlerisch gemacht hat. Sodass man in der Tat die künstlerische Sprachgestaltung wieder nachfühlen kann auch in der bewegten, der stummen Sprache der Eurythmie.

So soll sich also gerade daran zeigen, dass hier nicht versucht wird, mimisch oder pantomimisch nachzubilden die Humoresken, den humoristischen Inhalt, sondern zu zeigen, wie die künstlerische Lautform umgesetzt wird in eurythmische, stumme Bewegungsformen.

Aber auch das ist nur ein Anfang - mit dem lyrischen Teil oder demjenigen Teil des Dramatischen der Szenen, die ins Übersinnliche hinüberführen. Dagegen wird es mir eine Aufgabe für folgende Zeiten sein, das Dramatische selbst, die dramatische Darstellung durch die Eurythmie in einer gewissen Weise zu befruchten. Das muss natürlich ganz anders sein, als was Sie heute schon schen können. Was wir jetzt schon bieten können, mögen Sie mit Nachsicht aufnehmen - wir sind selbst unsere strengsten Kritiker. Aber wir wissen auch, dass in dieser Eurythmie Entwicklungsmöglichkelten sind, die vielleicht noch durch uns selbst - wenn die Zeitgenossen dem Interesse entgegenbringen - oder aber durch andere zu einem vollkommenen Kunstwerk diese Eurythmie ausgebildet werden [können] und [wir wissen,] dass diese eurythmische Kunst eben als eine vollberechtigte Kunst neben die anderen, älteren Kunstformen wird hintreten können.