The Building Concept of the Goetheanum

GA 289

28 February 1921, The Hague

Translated by Steiner Online Library

4. The Building Thought of Dornach

My dear guests!

I must ask you to excuse me for speaking in German and not in Dutch; however, I will have to show you a number of photographs to illustrate today's lecture, and they will not be in German, but international.

The anthroposophically oriented spiritual movement from Dornach has been working on this for the last twenty years or so. In the early years, however, the Anthroposophical Society was a member of the general Theosophical Society, but I never put forward anything other than what I currently represent. And when, after this anthroposophy had been tolerated for a while within the Theosophical Society, it was then found to be too heretical and was to a certain extent expelled, the Anthroposophical Society was founded as an independent society.

The anthroposophical movement definitely wants to reckon with the scientific attitude of the contemporary civilized world, it does not want to be anything sectarian or the like, but it wants to have a serious stimulating effect on the various sciences of our time, on the religious consciousness and also on the artistic and social life of the present.

By around 1909, the anthroposophical movement had grown to such an extent within Central Europe that it was impossible for it to work without its own building, and so a number of long-standing members came up with the idea of erecting their own building for anthroposophy. And when I was approached with the intention of erecting such a building, a very specific impulse immediately arose from the nature of anthroposophical work. Otherwise, if one had been forced by some spiritual movement to construct a building of one's own, one would have gone to some master builder and had him construct a Renaissance building or a Gothic building or a Greek building or something similar.

It would have been impossible for anthroposophically oriented spiritual science to proceed in such an outward manner. For this is not something that merely seeks to spread a theoretical culture, but anthroposophically oriented spiritual science emerges from the source of the full human being. I have taken the liberty of explaining how it emerges from this source of full humanity in the two previous lectures here in this hall. But because this is so, because anthroposophy is not merely a one-sided theoretical science, but because it is something for the whole of human life in all its forms of activity, this anthroposophical movement also had to create its own architectural style out of its sources at the moment when it was faced with the necessity of erecting its own building. And we have succeeded in creating such a building. It is not yet finished, but it is already finished to such an extent that courses were held in it last fall and will be held again at Easter. We have succeeded in erecting such a building on the Dornach Hill near Basel in Switzerland.

I said that the style of this Goetheanum, the attempt at a new style of building, was also formed from the same sources from which spiritual science was born, naturally with all the dangers, with all the shortcomings with which such a first attempt at a new style must be associated. Anthroposophy really emerges from the sources of being, not from thoughts or mere experimental and intellectually extended investigations, from the sources of existence itself. Therefore, in all its work, it must connect itself with the creative forces that are active in nature itself, for example, because the ultimate creative forces in nature are, as I have explained in the previous lectures, themselves of a spiritual nature.

I may perhaps use a comparison. Take a nut. It has a nut kernel; this nut kernel is formed in a lawful way. But there is also the nutshell; it could not be otherwise as it is, since the nut is as it is. The same force that shapes the nut kernel also shapes the nutshell in a unique way. Just as the nut kernel is shaped by natural law, so is the nutshell.

In Dornach, anthroposophical spiritual science is taught from the podium. The results of anthroposophical spiritual science are explored. Artistic representations are offered which are an outward expression - artistic, not symbolic or straw allegorical, but artistic - of that of which spiritual science itself is the expression. Therefore, around all this, around the kernel, so to speak, the shell must also be formed, which is [formed] precisely out of the same laws.

Therefore, an architecture has been cultivated in Dornach that is [designed] from the same sense, from the same spirit as anthroposophical spiritual science itself. Sculpture is done there out of exactly the same spirit, painting out of the same spirit. When someone stands on the podium and speaks in ideas, it is just another form of expression of what the pillars speak, what the paintings on the walls speak, what the sculptures speak. Everything is, if I may put it this way, cast from a single mold.

People are so afraid that nothing artistic would be created in this way, but only something symbolic or allegorical. Well, ladies and gentlemen, in Dornach there is not a single symbol, not a single allegory, but everything is attempted to be given in artistic form. The aim is not to somehow embody the ideas that are presented through images, that would be inartistic. Rather, the one spiritual life that underlies it can be shaped artistically at one time, and at another time it can be shaped ideally, in thought, scientifically. Art in Dornach is not a didactic expression of a science, for example, but it is one representation, and science is the other representation of the same great spiritual unknown from which anthroposophical spiritual science draws everything it wants to give humanity.

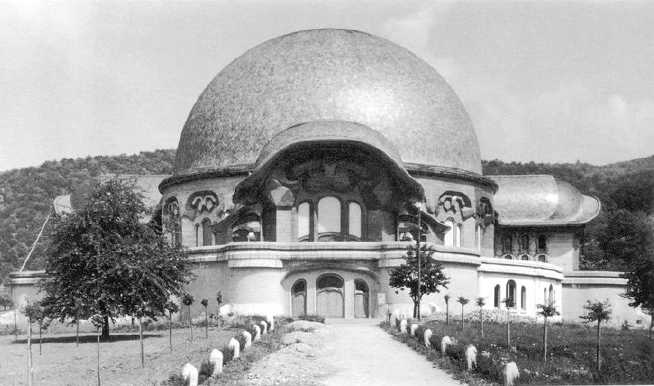

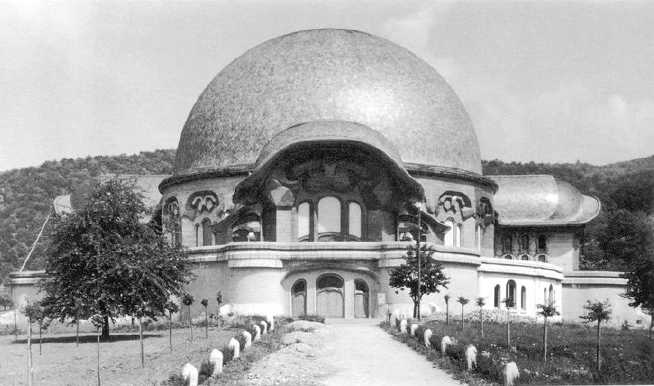

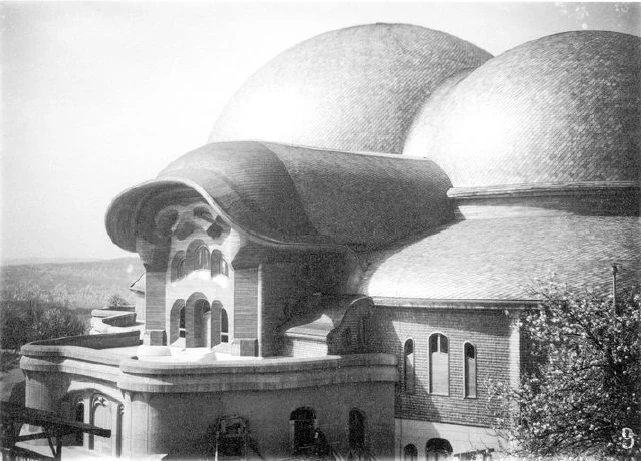

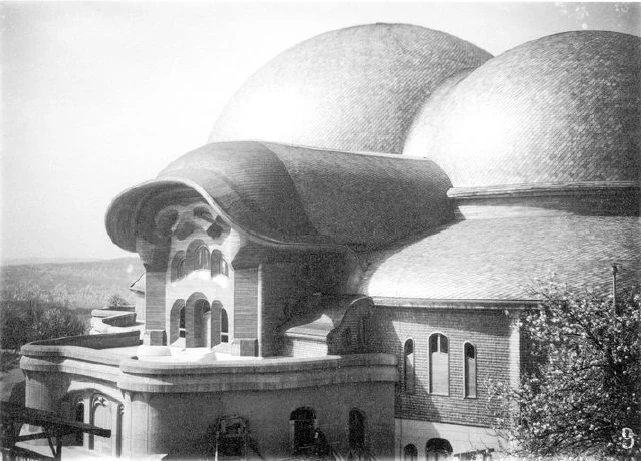

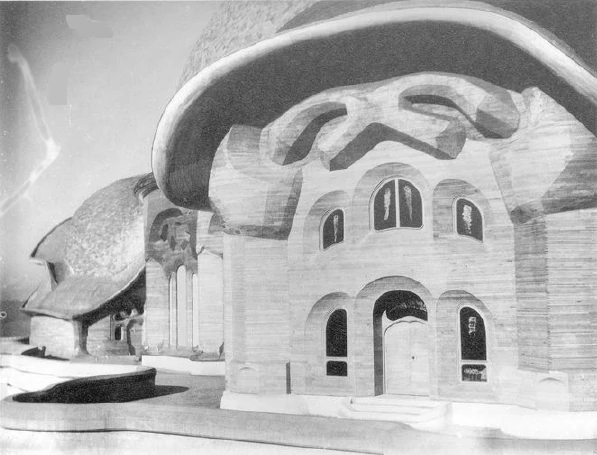

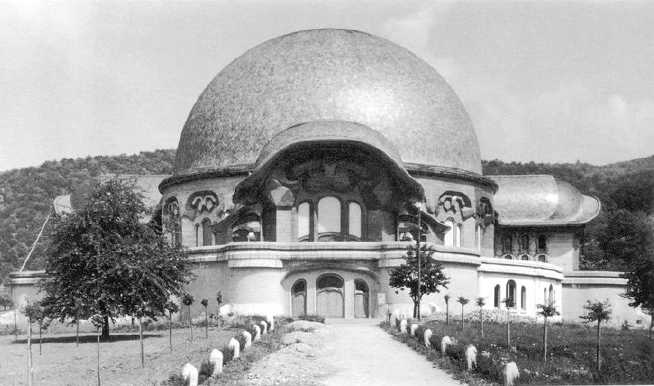

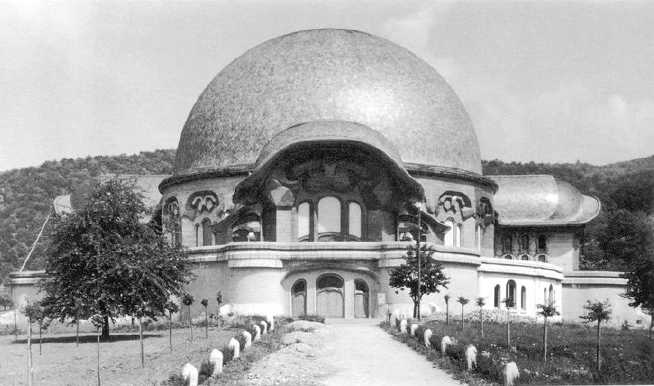

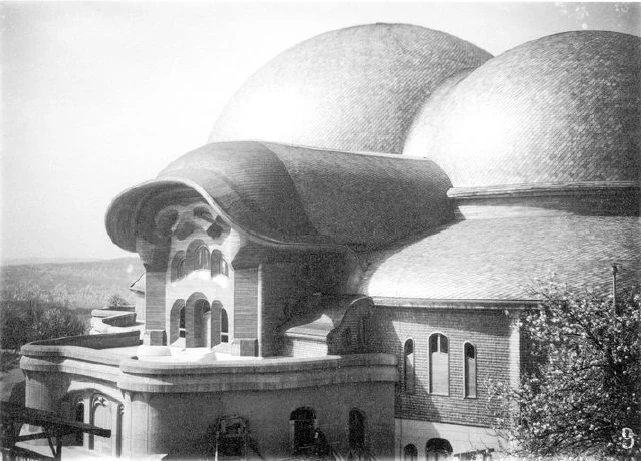

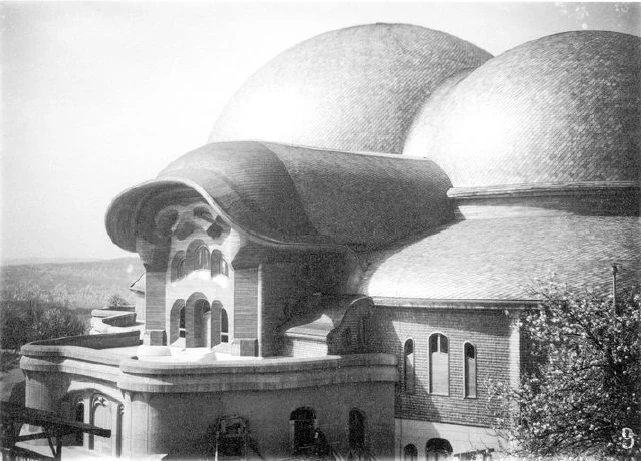

The entire external design of the Dornach building had to be accordingly. Anyone who looks at this Dornach building will see a double-domed structure, with two circular cylinders standing side by side, but interlocking, and two hemispherical domes above them, which are joined together in the circular segment by a somewhat difficult mechanical construction. Since in Dornach what can be researched through spiritual science is to be brought to the world, this must be reflected in the building itself. The small domed building is a kind of stage in which mystery plays and the like are performed. Eurythmy is also performed, but many other things are planned. The podium for the speaker is located between the small and large domed rooms. The large dome room is the auditorium or audience room for almost a thousand people. This double-domed building expresses the fact that anthroposophical spiritual science has something to say to the world of the present and the future in spiritual, general human and social terms, which I took the liberty of discussing in the two previous lectures.

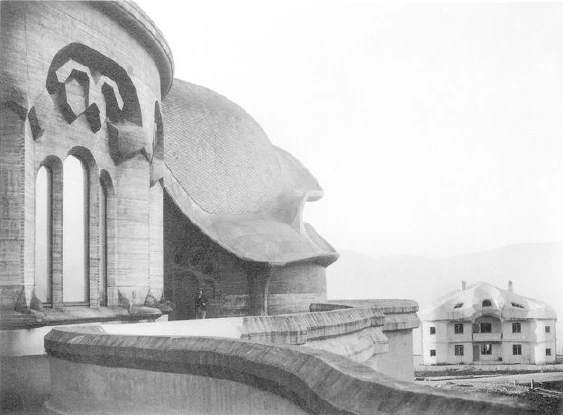

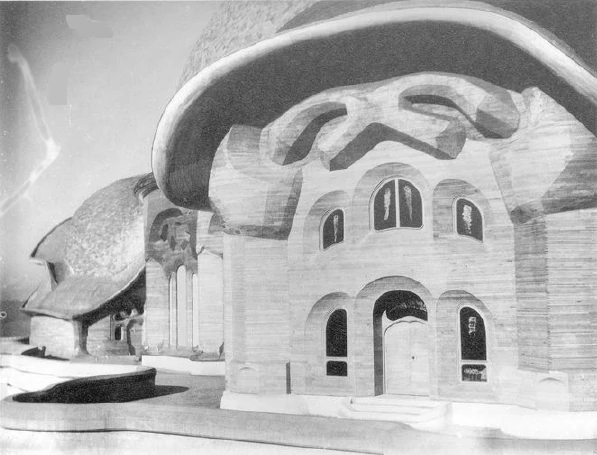

If you approach the building from the west [and] come towards the main portal, which is oriented to the west, you will first see the following view (Fig. 5). The bottom of the building is made of concrete; at the top is a terrace that leads around the building in a stylized curve. This wooden structure stands on this concrete foundation. The domes are covered with that wonderful Nordic slate that is found in the slate quarries that can be seen on the journey from Kristiania to Bergen, from the Vossian slate quarries. This slate fits in wonderfully with the main idea of Dornach. Concrete and wood are both processed in such a way that an architectural style emerges which can be characterized as the transformation of the existing geometric, symmetrical, mechanical, static, dynamic architectural styles into an organic architectural style. Not as if any organic form had been imitated in the architectural forms of Dornach, that is not the case, but rather I tried, in the sense of Goethe's theory of metamorphosis, to become completely integrated into the natural creation of organic forms and to obtain organic forms which, by metamorphosing them, could then form a whole in the Dornach building; organic forms which are such that each individual form must be in the place where it is.

Imagine the nature of organic forms. Think of something seemingly quite insignificant in the organic form of the human organism: an earlobe. You will have to say to yourself: This earlobe, in the place where it is, could not be otherwise, as it is, if the whole organism is as it has just revealed itself. The smallest and the largest thing in an organic context has its very specific form at its place in the organism. This has been carried over into the building concept of Dornach.

I know very well how much can be objected to this organic principle of building from the point of view of the old architectural styles. But this organic building style was once coined in the Dornach building concept. It may be rejected from the old point of view, but after all, everything new was rejected from the old point of view. In any case, however, if one can make friends with the transformation of static-dynamic, geometric building forms into organic ones, then one will find that all transitions from one organic form to another - not organic [natural] forms, for nothing is naturalistically imitated - [can be experienced] with the same inner regularity as, say, the plant leaf that is at the bottom of the stem, metamorphoses when it appears further up the stem, always [is] the same form, but alternating with the greatest variety.

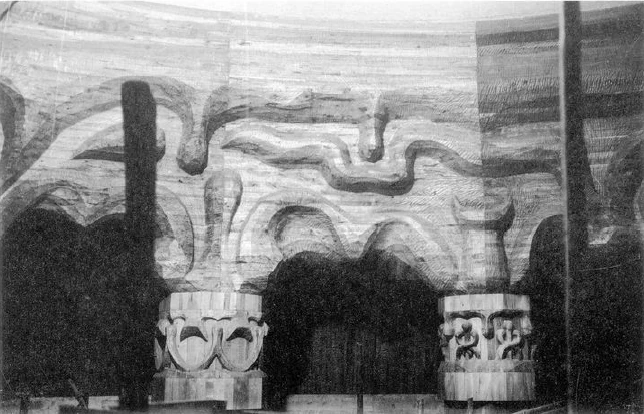

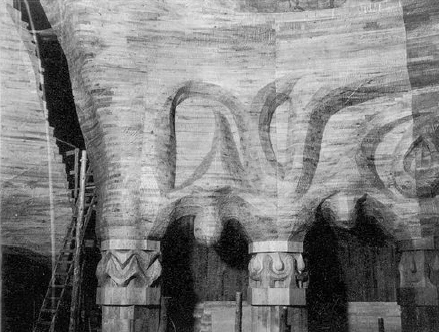

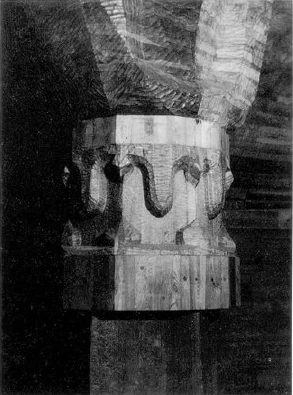

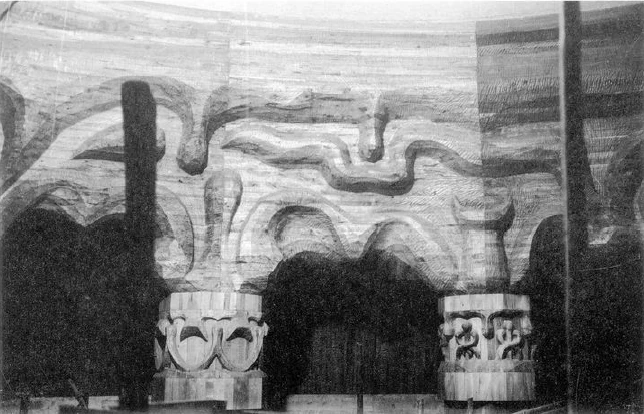

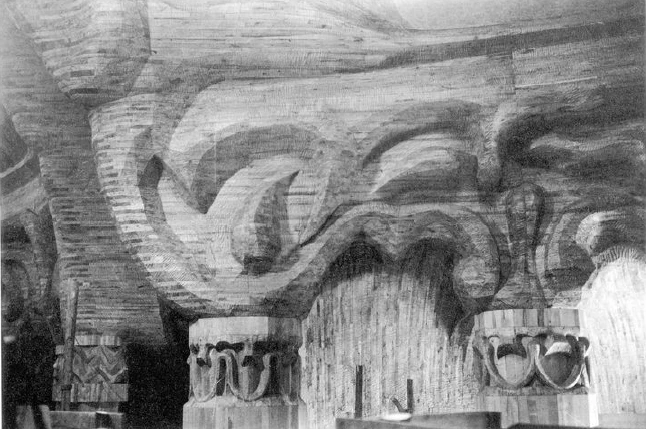

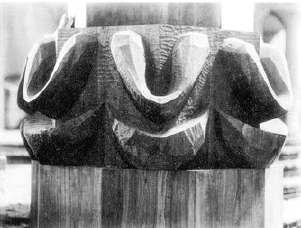

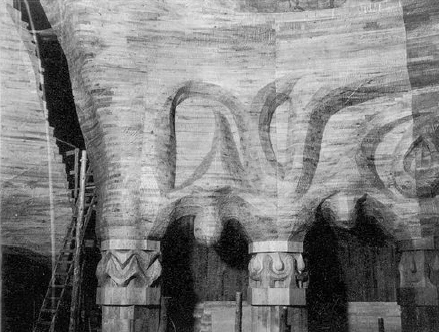

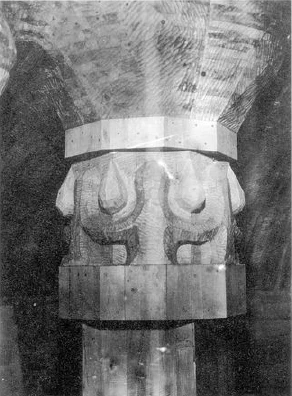

So in Dornach you will find certain organic forms carried into the building concept everywhere, as they are carved out of the wood here, as they appear here on the entrance pillars as capitals. Here on the side windows (Fig. 4, 12) you can see the same motif, on the windows of the side wing (Fig. 13) too, apparently no longer similar, but nevertheless the same metamorphosed, just as the motif of the green leaf reappears in the flower petal.

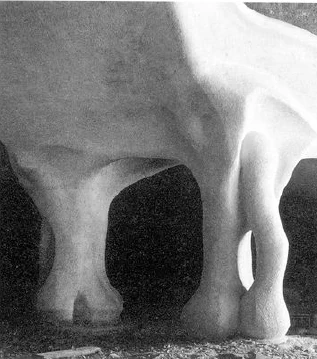

If you look at the building from the inside and the outside, you can get the impression: If any motif is near the gate, it is worked differently, so that you can see that the motif has less to bear against the gate, while it has to brace itself against the whole weight of the building. All of this, as it is taken into account in nature in the formation of the bones and muscle shapes, is definitely carried out in Dornach's building concept. Take a look at the bone form within the formation of the knee, it is designed in a wonderfully natural and ingenious way so that certain bones, which form the foundation bones, carry what lies on them. They are expanded and retracted in the right place. Feeling one's way into the forms of organic formation, of carrying, of weight, that was necessary in order to build Dornach.

Here (Fig. 5) you enter. Here is a room to put down your clothes, here is a staircase inside, through which you walk up. You can walk around this terrace and at the same time have a distant view over the countryside, the Swiss Jura.

The same picture, slightly shifted and closer (Fig. 6).

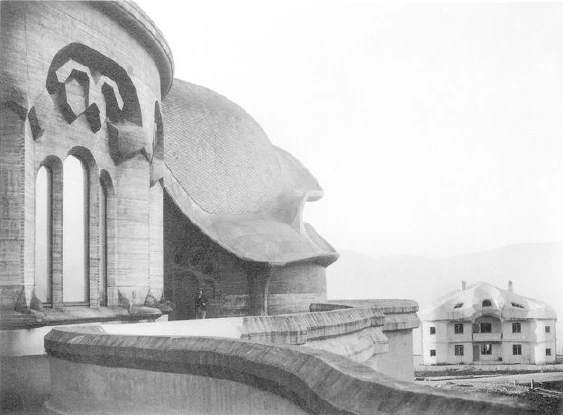

Here (Fig. 7) you can see the building as it presents itself to you from the southwest. Here the gallery, below the concrete building.

The building as you see it when you approach it from the north (Fig. 1), so that you have the large dome in front of you, [here] the small dome. Here the two domes are joined together.

From a point in the north, the building (Fig. 2). Here you can see a strange structure. This is the one that is most criticized. It is the building that stands near the building. I started by looking at the lighting and heating machines as if they were the kernel of a nut, and constructing a shell over it out of concrete, which is extremely difficult to work with artistically. Those who still criticize this building today don't consider what would be standing there if no effort had been made to create something artistic out of the artistically brittle concrete material: there would be a red chimney. I would like to ask people whether that would be more beautiful than what is certainly a first attempt to stylize something out of concrete, which has some shortcomings, but is nevertheless a first attempt to create something artistic in these things.

Here (Fig. 3) the building seen from the northeast. Here is a house that was already standing when we were given the building plot. A house that we very much hope we will be able to buy one day. You can imagine for what purpose we would like to acquire it; of course it disturbs the whole aspect of the building.

Here is the interlocking of the domes (Fig. 17). Here the main wing, here the main entrance (Fig. 10).

Here is the studio where the stained glass windows were made (Fig. 103). It was listed as a studio for grinding the stained glass windows.

Behind it is the boiler house again (Figs. 106, 107). In a neighboring village, Arlesheim, there is a particularly tastelessly built church. I have nothing to say against it, but it is honestly tasteless. Nevertheless, the Swiss Association for the Beautification of Swiss Buildings has managed to say that this [our] building disfigures this part of Switzerland: just take a look at the beautiful church in Arlesheim.

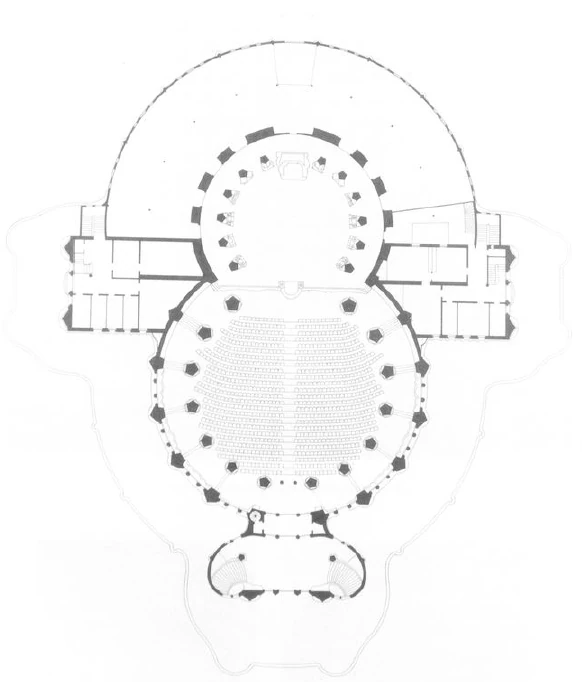

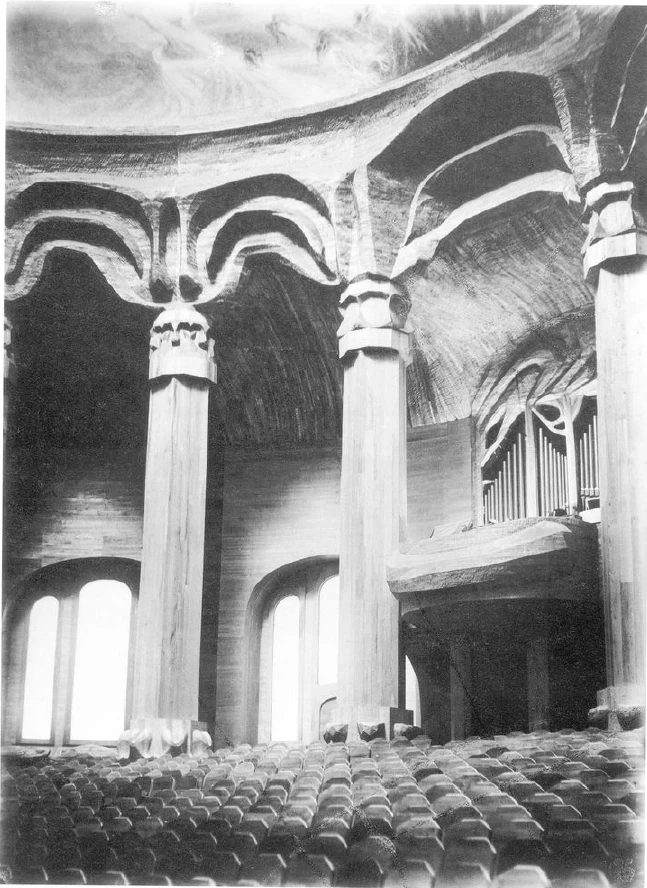

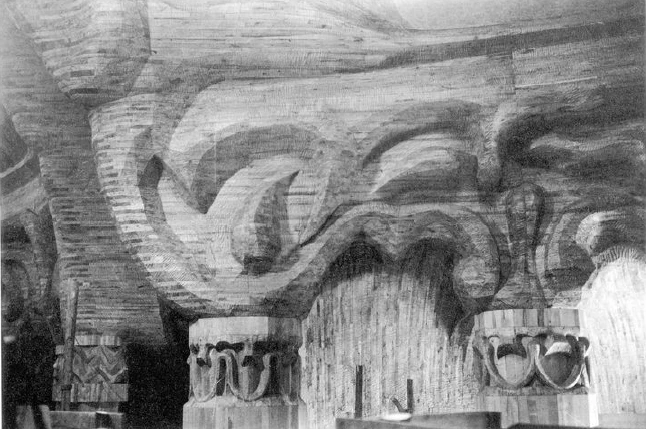

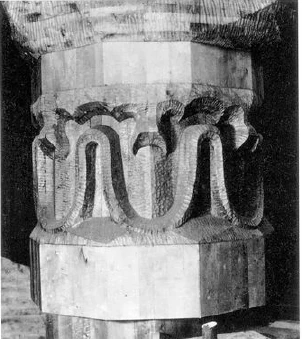

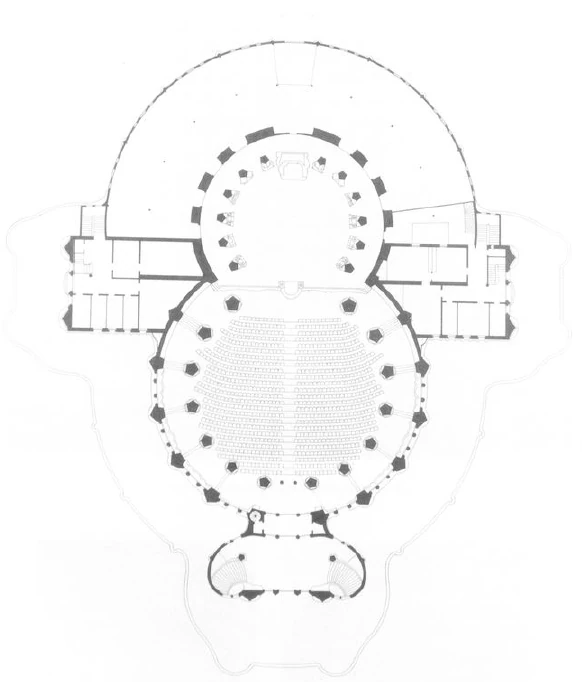

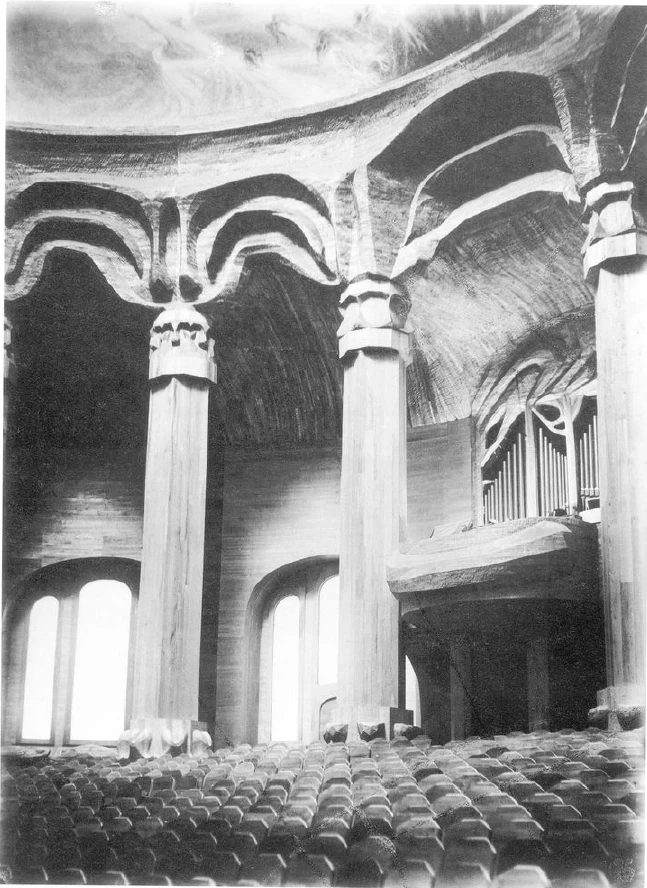

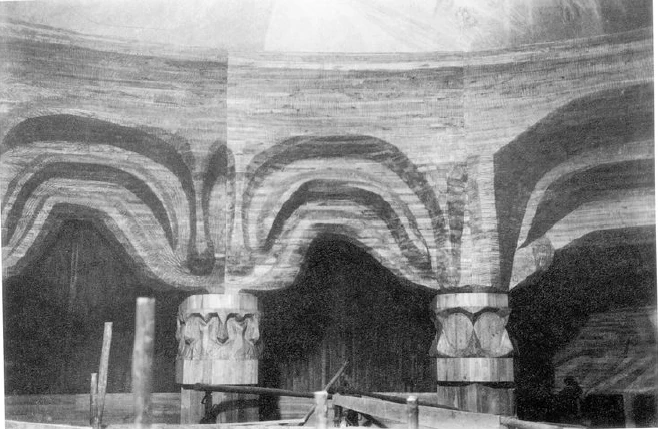

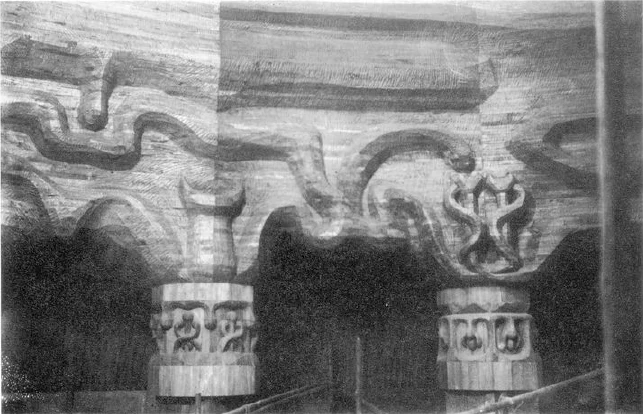

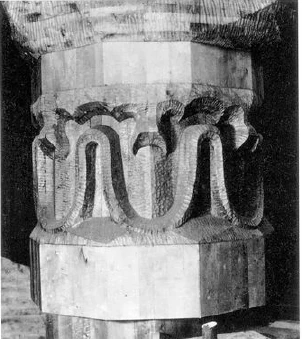

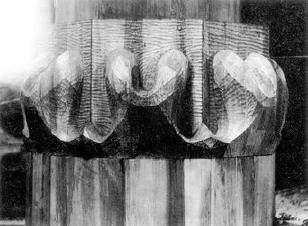

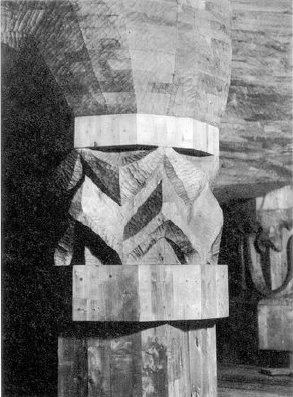

The ground plan (Fig. 20). Main entrance, organ room, auditorium. Here is the lectern. The stage area. Here are the two side wings with the individual rooms for the performing actors and other artists. Here you can see seven columns on both sides. Here in the curve six columns. These seven pillars are not formed out of some mystical urge in the number seven, but purely out of artistic feeling. Just as the violin has four strings, so the artistic feeling here has resulted from inner reasons that a certain artistic development and in turn an artistic conclusion can be achieved by developing just seven motifs. With these pillars, the risk was taken not to design the capital and architrave motifs as repetitions, but in a lively development. When you enter from the west portal, you come across the first two columns. However, they are symmetrical. But if you move on from the first to the second column, the capital of the second column, the base, the architrave above the second column is designed in a way that must be organic. It is designed in such a way that one had to live into the creation and creation of the forces of nature if one wanted to artistically shape the second pillar motif out of the first, the third again out of the second and so on, until a certain conclusion was reached in the seventh pillar motif.

Many visitors come to Dornach and ask: What does the individual chapter mean? You can't ask that at all about art. The essential thing is that one pillar emerges artistically and formally from the other pillar. Whereas in the static architectural style we are actually only dealing with symmetry, with repetitions of the same motif, here we are dealing with a living evolution from the first to the seventh column. I will show the columns later, then you can see this.

Section through the building (Fig. 21).

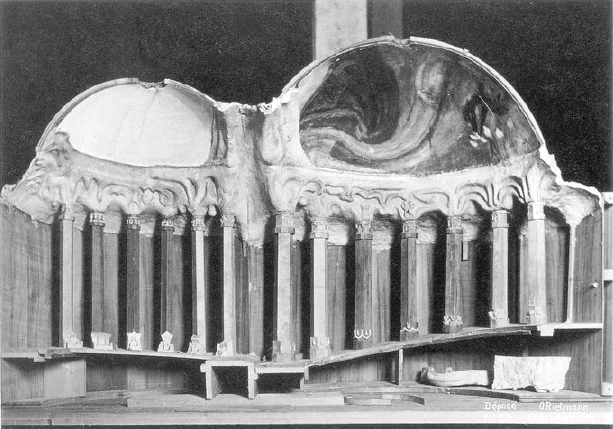

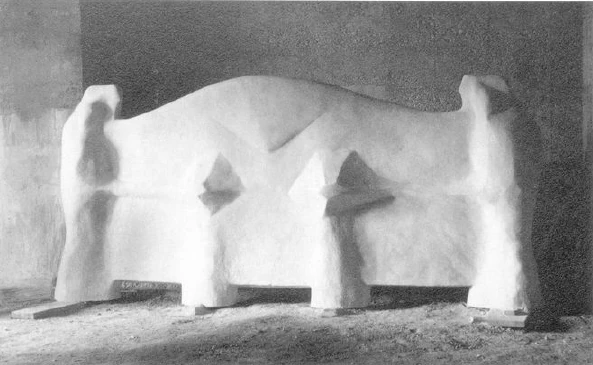

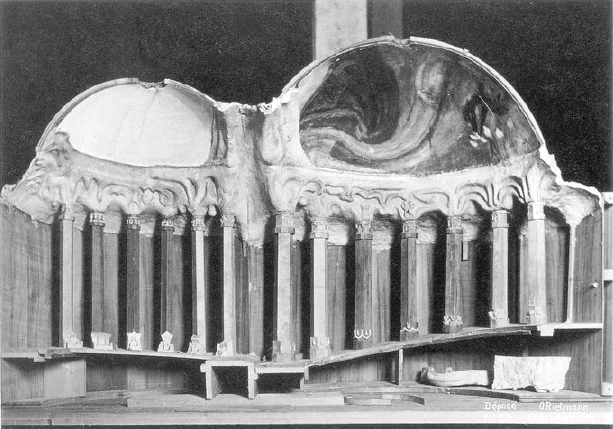

Original model, cut vertically in the middle (Fig. 22). I originally had to work out the whole building as a model, so that even the building plan, ground plan and elevation, as they were based on, were formed according to this model. This whole model is precisely the embodiment of the Dornach building concept, is conceived in the same way as spiritual science itself is conceived, is to a certain extent another expression for that for which the one expression is spiritual science itself.

Right next to the main entrance, the main portal in the west (Fig. 15). The pictures were taken at a time when construction was still in full swing.

A little further on from the main entrance (Fig. 12). Here the part containing the stairs to go up. Here is a house nearby. This house was built in a very special way. After all, we built the entire structure through the understanding of our anthroposophical friends. The fact that the Dornach hill was used to build this house is explained by the fact that a friend in Basel, near Basel, bought this building plot a long time ago to build a summer house for himself; he then gave us this plot as a gift. We were then able to build there. The friend also wanted to have his house here. And that's when I was given the task - various conditions made it necessary - to stylize a house, a family home with fifteen rooms, out of concrete material. It was a bit of a gamble. There are certainly still flaws in this house, which is formed out of the artistic nature of the brittle concrete material. But such things have to be done for the first time.

A side wing (Fig. 17). These two side wings are inserted like a crossbeam. Here the main motif is again metamorphosed. Everywhere the same and yet again something different, one could say, is contained in the building forms.

Front façade of a side wing (Fig. 14). Here again the motif that is at the main entrance, very widened, designed with rich material, here once more sparingly designed in the same metamorphosis. A certain law of symmetry is observed everywhere, but this is combined with asymmetry. This asymmetry gives the building an artistically pleasing effect and great variety.

Taken somewhat larger, the motif of the façade of one such side wing (Fig. 11).

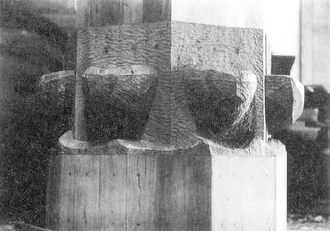

We enter through the concrete entrance in the west, imagine (Fig. 23). Then we first come to the stairs leading up here. This would be the room where you put your clothes. Then you go to the front, here you enter the auditorium. Here I have dared to make the column shape organic.

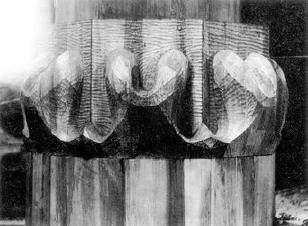

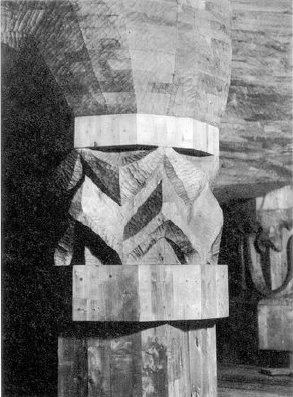

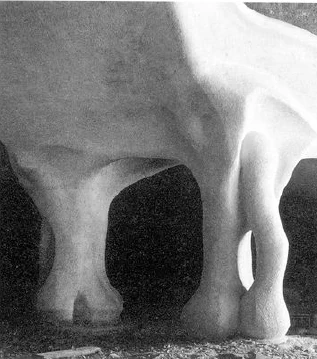

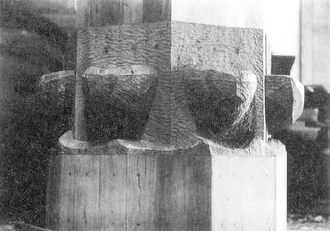

[Then] for example this shape here (Fig. 24): There are three motifs standing perpendicular to each other. How did this form come about? Not through any kind of philosophizing, but purely out of feeling. You can say to yourself: anyone who has first entered through the main portal and then wants to come into the auditorium must be able to move in a certain way towards the thought and feeling of what he wants to hear in Dornach from an anthroposophically oriented spiritual view: Here you may enter for the security of your soul, to gain a firm foothold within yourself. Here you may enter in such a way that no illusions of life shall beguile you; that no kind of wavering shall come over you. This has been sensitively expressed here in this motif.

Then you see here a pillar supporting the staircase (Fig. 25). The staircase motif itself is designed in such a way that it is organically braced against the building, in this case against the exit. Here it is carried by a column that does not imitate organic motifs in a naturalistic way, but is just as organically shaped as the forms of living creatures in nature are shaped by the creative forces of nature. How this pillar stands up, how it supports something on one side, where the load to be carried is lighter, how it braces itself against this side, where the main load of the building lies, is expressed in the smallest things in the same way as the earlobe shape expresses the affiliation to the whole human organism. Every form in Dornach must be perceived as a necessity in its place.

Here (Fig. 26) is a motif that I have executed in the various metamorphoses. Here it is made of concrete, in the upper section of wood. It's a front piece for a radiator. As I said, in Dornach the individual forms emerge from each other in a metamorphic way, and there are no abstract forms that are merely appropriate to the underground art, but everything is realized in a strictly organic artistic way.

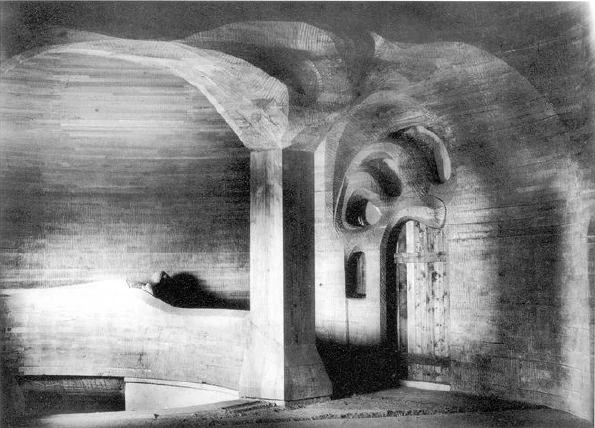

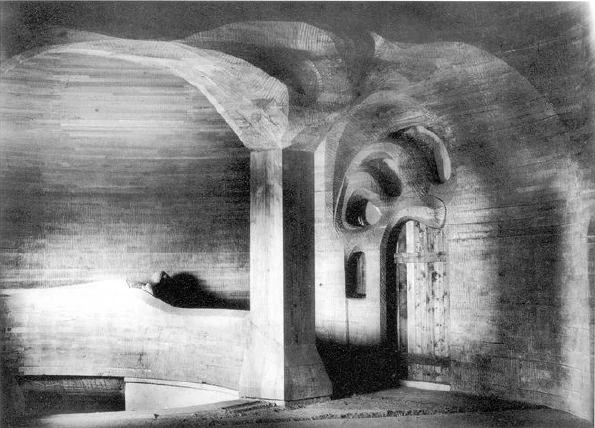

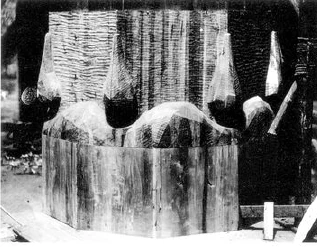

Here (Fig. 27) you can see the room that you enter when you climb the staircase that has just been built. This is a wooden building. Here is a pillar supporting the ceiling. Everything that immediately follows in the interior is handcrafted by a large number of our friends. It must be emphasized again and again that a large number of friends have gathered in Dornach over many years, all of whom have worked out these individual sculptural forms, which were given to them in the model, by hand. In a sense, the entire wooden structure is the handiwork of the anthroposophical friends. And that is something that could have been exemplary at the same time for the loving cooperation of a group of people.

If you now enter and look backwards in the auditorium, you can see the organ loft here. This is the model (Fig. 30). The idea is not to place the organ in a cavity, but to take the organ and shape the architecture accordingly. Additional motifs were then added during the elaboration.

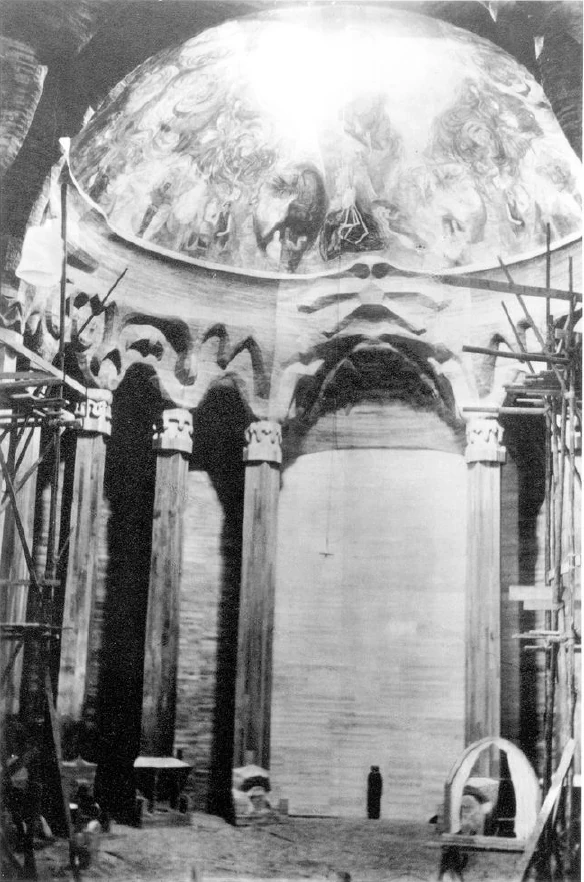

Here is the interior (Fig. 29). When you enter the interior, you can see the organ porch where the singers stand. Here are the first three columns. I will explain the picture of the column formation in a moment. Above the columns are the architraves, which also show progressive motifs.

Here is the organ loft (Fig. 28).

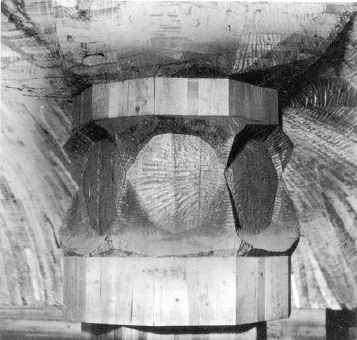

Here is the space above the organ, sculpted out of wood (Fig. 33). Please take a look at the chapter. It is composed of simple forms. We will make the transition to the next and next capital and architrave forms. You don't have to think about how one capital emerges from another, but it is simply perceived like a leaf on the stem of a plant from which others now emerge metamorphically. Thus the next motifs here are always formed quite sensitively from the previous ones.

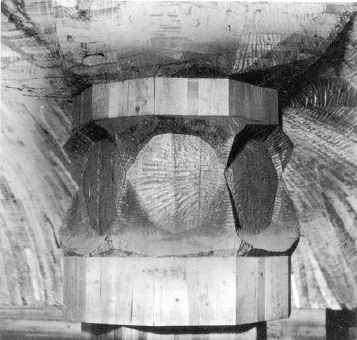

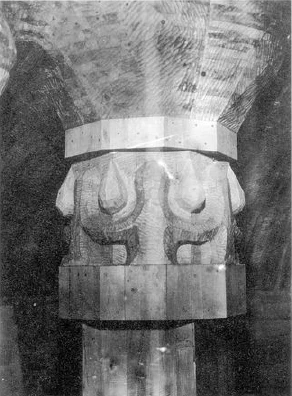

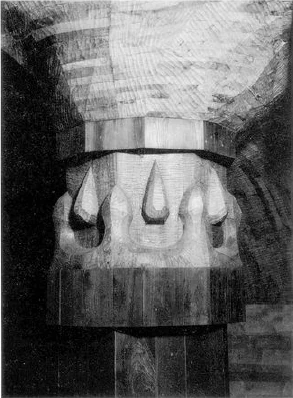

Here you have the simple capital motif of the first column (fig. 34).

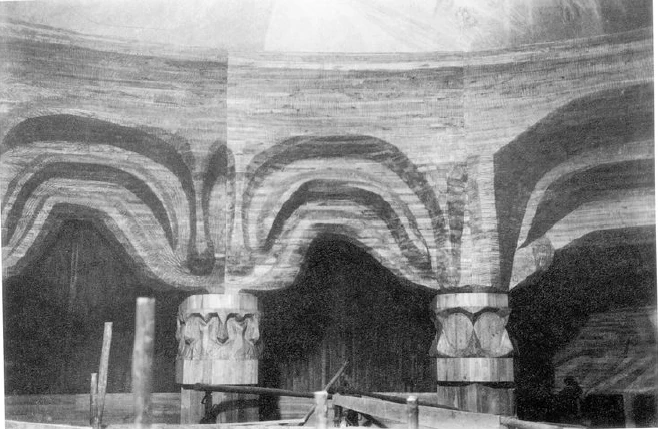

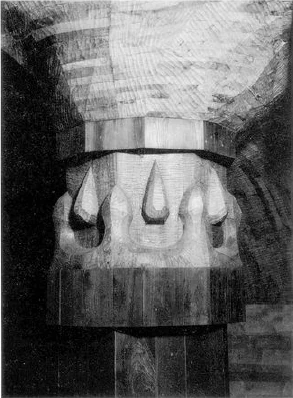

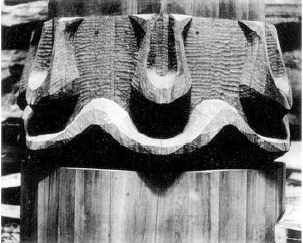

The first column and the second column (Fig. 35). If you think of the simple motif from top to bottom, from bottom to top, you can imagine how it grows. The drops from above grow into this form, and from below the forms grow to meet them in more complicated shapes. It is the same with the architrave motifs.

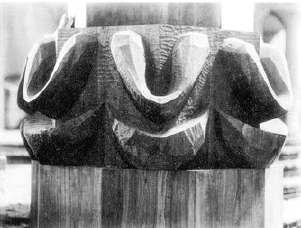

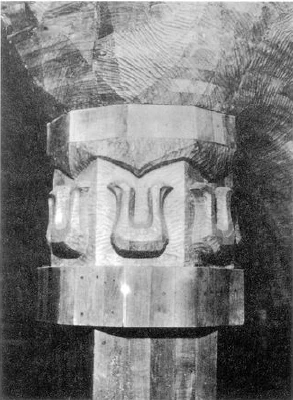

Second column motif (fig. 36): already more complicated.

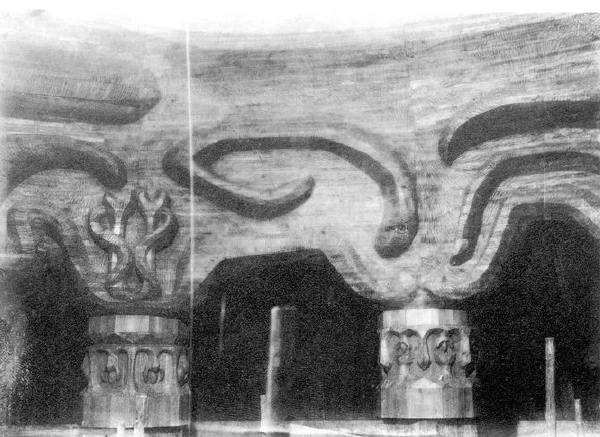

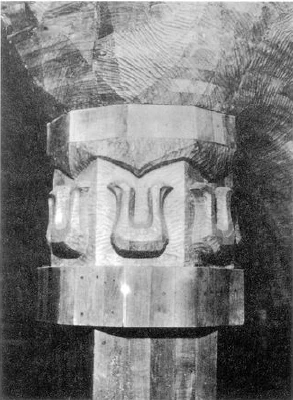

Second and third columns together (fig. 37): Again organically metamorphosed, the third column is obtained from the second column.

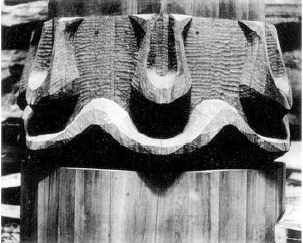

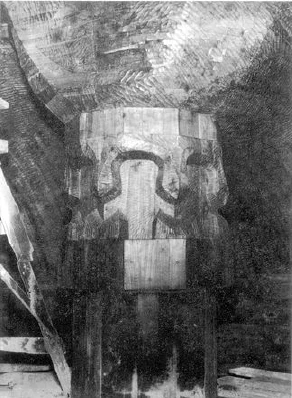

The third column on its own (Fig. 38).

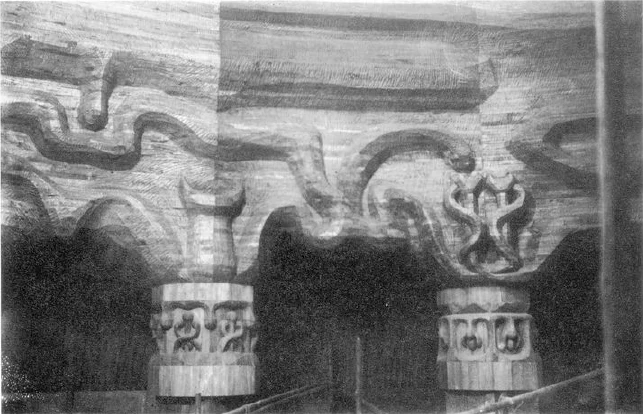

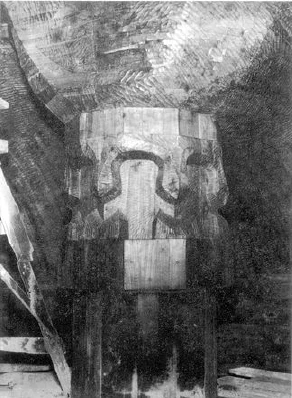

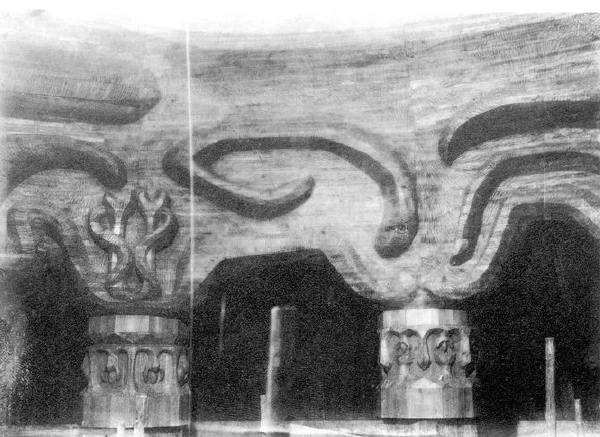

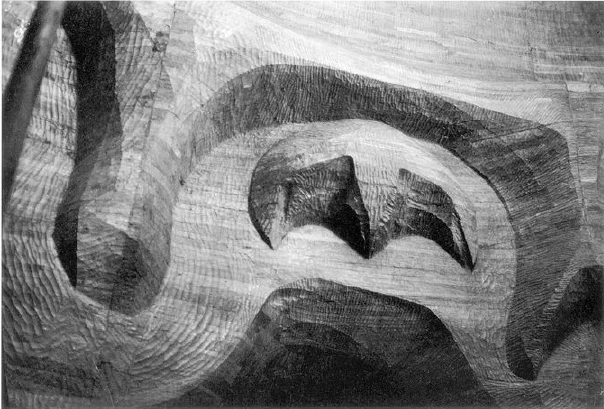

Third and fourth pillars together (Fig. 39). What is still simple here has become more complicated. You make very special discoveries in the process. I simply let one motif emerge from the other according to artistic feeling. In doing so, I realized that it is only through this artistic approach that one can really understand the essence of evolution in nature. One usually imagines that the first forms in a developmental process are the simpler ones, which then become more and more complicated. This is not the case. If you work artistically, allowing one to emerge from the other, then you end up shaping the simpler into the more complicated, but when the complication has reached a certain level, things become more harmonious, but simpler again. This is how evolution works: from the simple to the complicated and then back to simplification. This discovery is surprising at first. You create something like this from the purely artistic and then find that it actually corresponds fully to the artistic creation of nature.

Consider the human eye: it is the most perfect, but not the most complicated. Certain organs of lower beings, the fan in the eye, the xiphoid process, are absorbed by the human eye. You come to that by yourself if you shape purely artistically.

Something very strange also happened to me. I said I had to form seven pillars, really not out of any mystical inclination. The seventh pillar turned out to be the end; you couldn't go any further, the motifs had been fulfilled. But later I discovered that if I took the convex shape of the seventh pillar and reshaped it a little artistically, it went straight into the concave, hollowed-out shape of the first pillar. I wasn't looking for that. It was the same with the sixth and second pillars, and also with the third and fifth pillars. I discovered that the capitals and the pedestal figures were something that emerged naturally from the work in the sense of an evolution. This is not something I was looking for. Even in nature itself, such surprising formal relationships arise. When you create artistically, you get these things that confront you from the individual forms, and you come to a deep respect for the mysterious working and weaving firstly in nature, but secondly in the world of forms itself, which you can penetrate imaginatively and artistically and by looking at it.

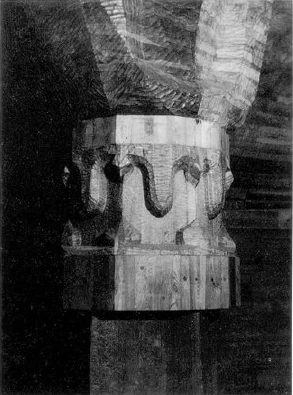

A column on its own has become relatively complicated (fig. 42). But you will see that by thinking of this motif in such a way that it grows from top to bottom, from bottom to top, something emerges that I did not aim for; but when people look at it, they will say: He has formed the staff of Mercury. I didn't want to form that, but it came out like that.

It spreads out, grows, thus creating this complicated motif (fig. 41), then the motifs become simpler.

Here you can see this motif (Fig. 43). Now I couldn't go any further in the complication. By thinking of it as growing and perceiving it as growing, I created this simpler motif.

The last two columns with their architraves above them (fig. 45). The column directly in front of the stage entrance (fig. 46).

In this way, you can see how the individual capitals came about, how the entire column motifs developed artistically in their evolution.

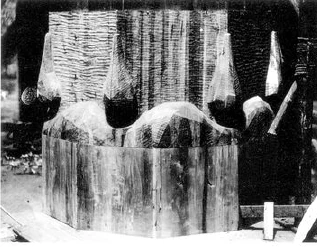

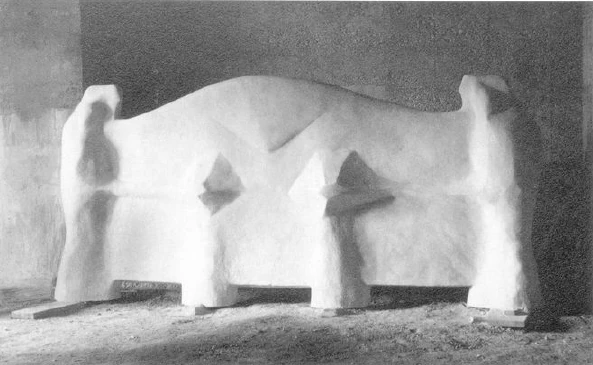

Here we are in front of a plinth (Fig. 48). I wanted to show these pedestals in turn, one after the other, how they develop apart in the same way as the capitals.

All pedestals (figs. 48-54). First becoming more complicated, then simpler again.

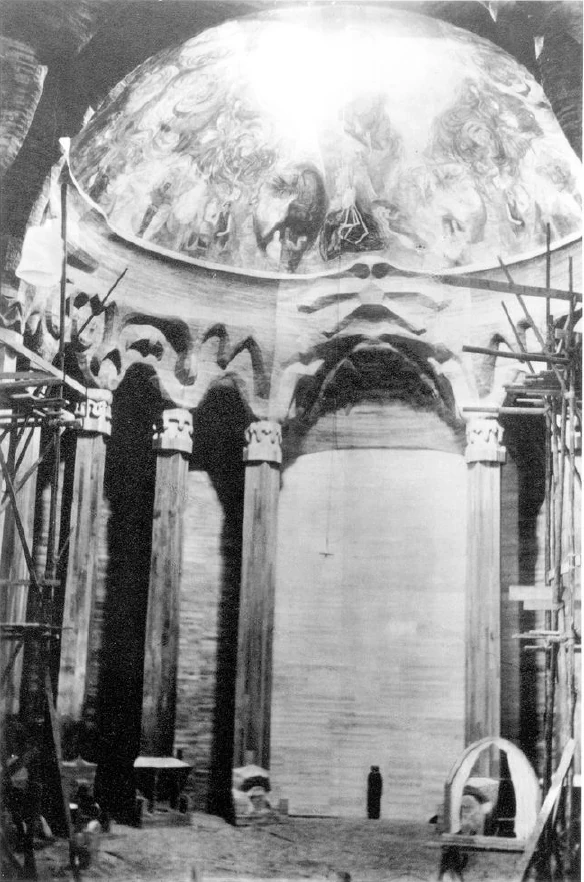

Here you can see from the auditorium into the stage area (Fig. 57). Here you can see the painted interior of the stage dome. Here the architrave above the columns of the auditorium. Here the auditorium closes off the stage area. Still in progress is the gap that connects the auditorium with the stage area (Fig. 56).

Another view from the auditorium, whose last columns you can see, into the stage area (Fig. 55). Here the painted stage dome. With regard to the painting of the two domes, however, I cannot give you such pictures, or rather I cannot give you pictures that speak as clearly as I can about the other. For with regard to the painting of the Dornach building, what I once described as the essence of modern painting has been very seriously striven for and followed, at least in the small dome room. Everything that is created in painting must be extracted from color.

The world of color is a world unto itself. The person who immerses himself in the world of color learns to recognize the creativity of each individual color; he learns to recognize the creativity that lies in the harmony of colors. Those who know how red affects human perception, how red speaks from within, those who know that blue has a formative, creative effect, come to shape the painterly world out of the colors

This is roughly what they tried to create when painting the small domed room in Dornach. The essential thing is always, if I may put it this way, the spot of color in a certain place. Although the figurative is born out of color, everything is originally conceived out of color. Light, dark and colors are actually the only things that are justified when you depict something painterly with the help of the surface; drawing is actually a mendacity. Take the horizon line: the blue sky above, the greenish sea below. If you paint it like this, then the horizon emerges by itself as the creature of the color encounter. And so it is with all lines in real painting. In painting, form is the work of color. This is what was attempted in Dornach.

There (Fig. 64) you first see what is under the dome, the architrave motif, directly above the group that is to be placed in the east of the building as the sculptural center of this building, so to speak. A motif from the small domed room (Fig. 66). I ask that these motifs be judged in the same way as those of the large domed room, except that six columns are intended on both sides; thus the whole shapes and designs are “ben other.

A capital motif of the small domed room (fig. 58-63).

The first thing in the painting of the small domed room when you enter it (Fig. 73). Of course, you will only get a real sense of what I can show you now when you feel this [photographic] reproduction in its defects, when you say to yourself: What is this actually? There should be color! Of course it is also color, everything is taken out of the color.

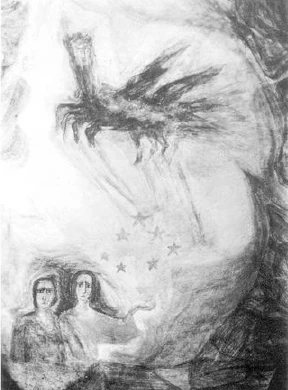

Here is a child flying towards a kind of fist figure (fig. 69). The child is red-yellow, the fist figure in blue.

Here fist (fig. 70), [here] the child (fig. 69). This fist figure roughly represents the civilization of the fifteenth, sixteenth century, in which we are actually all still immersed. However, that which takes shape from that civilization in external theoretical science is basically only a surface. The person who lives into the world view that has emerged through the newer natural sciences with his whole human being feels death strongly on the one side and budding, germinating life on the other. These two polar opposites confront us precisely from the present-day view of nature. Just take the following: The way we describe nature, we use terms that are basically taken from the dead, the mineral. Our natural scientists see an ideal in thinking of plant and animal life along the lines of the mineral, perhaps even being able to work experimentally in this direction. The idea of death is very strong (Fig. 71). On the other hand, if we delve into our self-consciousness, there is that life which is polar opposite to death, which we feel in particular when we allow the life of a child to affect us uninfluenced by knowledge. It is entirely in keeping with the feeling that a fist figure appears here, painted out of the blue.

[Here] the only word you will find in the entire structure: ICH (Fig. 72).

It is at this time, when this fist figure enters modern civilization, that we first really get to know the ego as the abstract content of self-consciousness. As you know, older languages still have the I in the verb. In this age, the ego is peeled out, set apart, when at the same time this culture appears, the political contrasts of which I have just described. This is the first motif that confronts us in the painting of the small dome.

Here Faust (fig. 70), here Death (fig. 71) as the contrast to the child. It is precisely the most modern cognitive and spiritual life that is to emerge in this motif, but out of the color, out of the yellow-reddish tone of the child, the blue tone of Faust, the brownish-blackish tone of this skeleton.

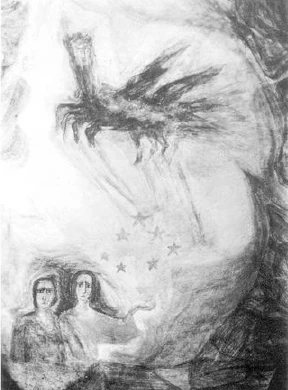

An angel-like figure above Faust (fig. 74). In a sense, everywhere below is a figure representing the more human, above it a spirit figure, the inspirer, the inspiring figure.

Here (fig. 75) is an image born out of the sensibility of Greek culture, i.e. more in the past. The fist figure was conceived out of modern culture, which we are still part of. Here is a kind of Pallas Athena figure, perceived from Greek culture, with the inspiring figure above it (Fig. 76).

Also such an inspiring, spirit-like figure (fig. 77).

Here (fig. 78) going further back an initiate of the Egyptian culture, above him the inspiring figure, so that everything worked out of the color is really intended here as figurative, which even represents the successive cultures and their evolution.

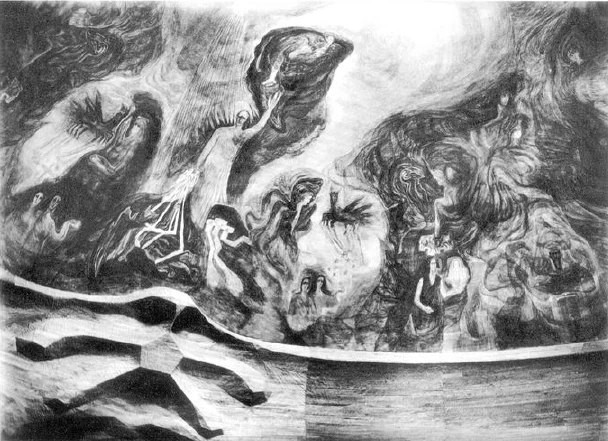

Here again two figures (fig. 79), and below them the figure that I will show you in larger size later. This is a kind of man of more recent times, a man of the present Central European culture. That which is ambivalent in this man of the present is expressed in his inspiration, which is above him. Here is a Luciferian figure. In this Luciferic figure there is to live all that which lives in that human nature, that through which man wants to go beyond himself, through which he falls into the rapturous, mystical, theosophical. The other, the Ahrimanic, through which he falls into the philistine, the intellectual-materialistic. These two opposites are in every human being today. Man seeks a balance between this duality. Everything in him that leads pathologically to fever, to pleurisy, is in this Luciferic form; everything that leads to sclerosis, to calcification, is in this Ahrimanic form.

Here (Fig. 81) you see one thing, in a sense the human being with those forces that age him, drive him towards sclerosis, drive him mentally towards intellectuality, towards materialism. Man would be like this, despite the fact that no one desires it so much, so Mephistopheleanahrimanic, if he had no heart, if he were merely a man of intellect. He is in all of us, but we also have a heart.

This (Fig. 80) is the one who represents us if we only had a heart and no mind. The Luciferic figure: rapturous, mystical, theosophical, everything that wants to go beyond the human being. Here is the human being who, with the help of these two again polar, contour-like opposing effects, really feels duality and can only bear it if the child is placed by his side. The man of the present in his ambivalent nature. Here (fig. 82) still somewhat larger, the same man who feels conflict within himself.

Here (figs. 83, 84) we come somewhat closer to the center. Here two figures, one painted more light, the other more dark. I have always taken the view that the Russian people's soul contains the man of the future. Today, only in the East is everything distorted. Today, through Lenin and Trotsky, the East is working towards the death of culture, towards the most terrible destruction. For all that which is at work in the East as forces of decline in the most terrible way can only lead to the destruction of all culture. But that is not what corresponds to the Russian national soul. And if nothing else would bring down Lenin and Trotsky, the Russian people's soul would one day bring them down. But the Russian people's soul is such that every Russian has his own shadow next to him. There is not only the ambivalent man as in Central Europe, who carries Lucifer and Ahriman within him, the enthusiastic and the materialistic, there is a man who has a second man beside him. This shadow must first be absorbed by the man of the future, but then he will also become the man of the future.

Here (Fig. 83) the inspiring angel, above it a centaur figure. When the man of the future will have attained his maturity, this figure will be that which may be put forward as the actual inspirer next to the angelic figure; today he is still centaur-like.

Here (Fig. 84) this centaur figure, the starry sky in between, so rightly sensing that evolution in the spirit which hovers between the angelic and the animal. Man stands, as it were, between the animal, which has assumed a human form in its passions and instincts, and the angelic, in which the ahrimanic is transformed into the spiritual and thereby receives its cosmic justification.

Here (fig. 85) from the other side, symmetrically situated, the angel, the centaur figure, carved out of the yellow.

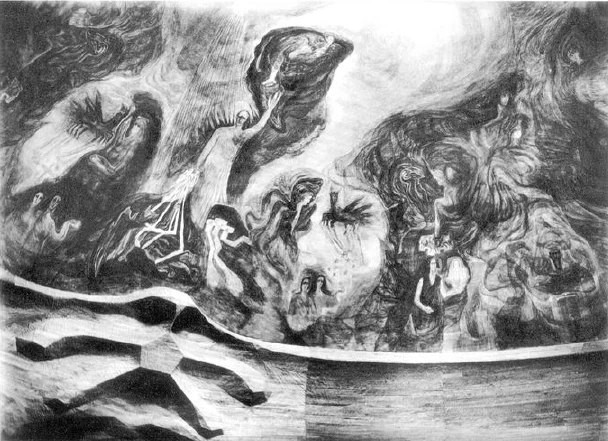

Here you can see what is painted in the middle: a kind of representative of humanity (fig. 86). Anyone who sees this representative of humanity may feel as if it were an embodiment of the figure of Christ. This Christ figure in the middle is shaped as I had to place it according to my supersensible view of the Christ figure, which I believed, as this being really lived in Palestine at the beginning of our era. The traditional figure of Christ with the beard was only invented in the fifth or sixth century. Today we have to go back through spiritual scientific research to the time when Christ lived in Palestine in order to be able to discover his form through extrasensory vision. I make no claim to be believed authoritatively that this is the true figure of Christ, but I see it this way and I hold from the depths of my being that this is the figure of Christ. Below it, carved into a rock, is the figure of Ahriman. From the right arm of the

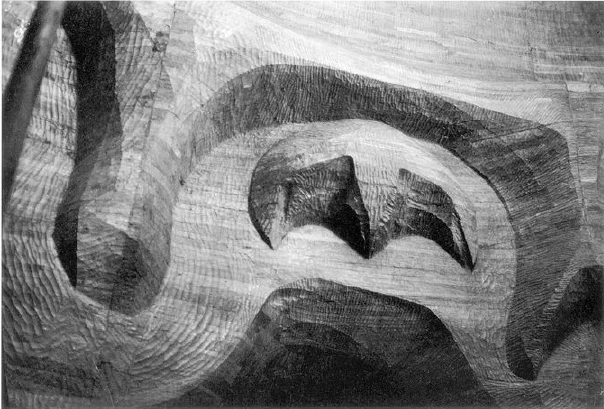

The figure of Christ emanates lightning bolts that snake around the ahrimanic figure. The Ahrimanic figure is everything that man would be if he had only reason, only intellect, only a materialistic attitude, not a heart. Above it is the figure of Lucifer, carved out of the red, all that which in man tends to rapture, to fantasy, to one-sided theosophy, to mysticism.

Here (Fig. 87) you see this figure of Lucifer, the face painted entirely out of the red, above the figure of Christ.

The Ahrimanic figure (fig. 88), the countenance - the wings are bat-like in the Ahrimanic figure - bound by the lightning bolts emanating from the hand of Christ. Of course, it all depends on how you perceive it from the color.

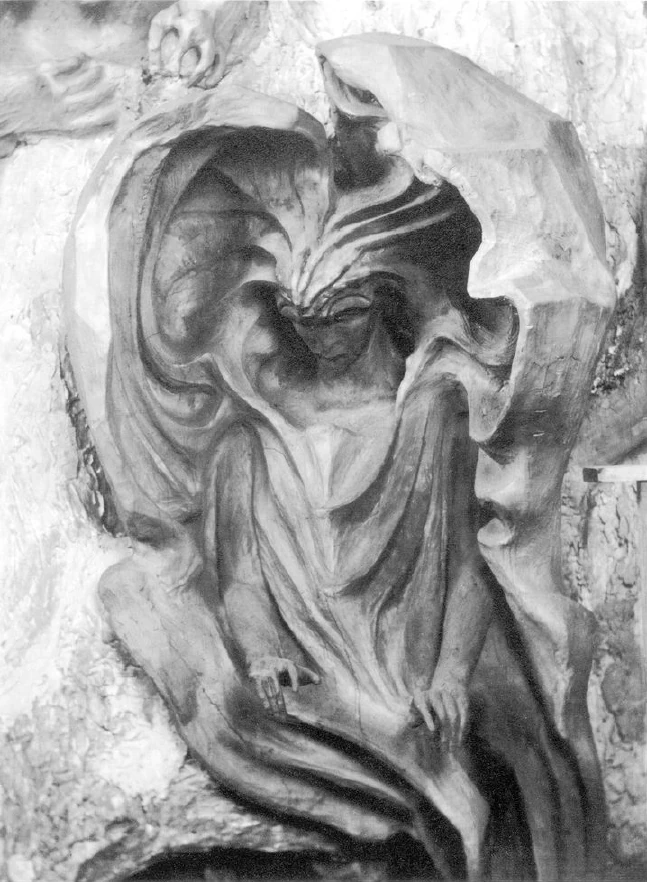

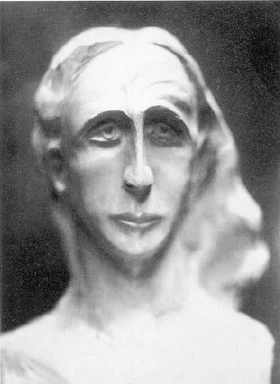

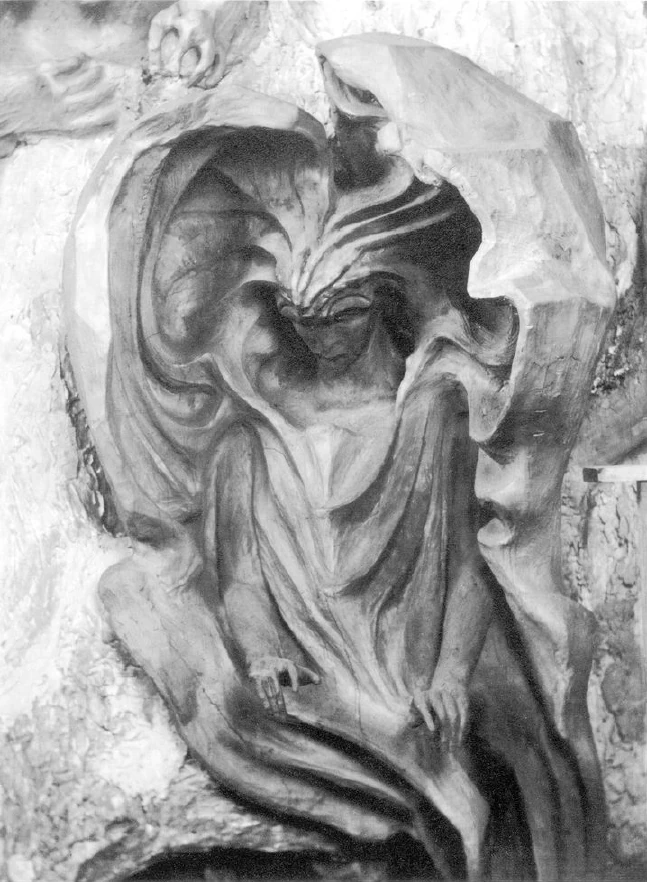

Here is the head of the Christ figure (fig. 90). This is what is painted into the dome at the very east end of the small dome room. Below this painting - Christ, Lucifer, Ahriman - is a nine and a half meter high wooden group (Fig. 93); again in the middle is the representative of humanity, who can be perceived as Christ. Twice above it is the Lucifer motif, twice below it the Ahriman motif. And then out of the rock an elemental being, which looks at the Christ in the midst of Lucifer and Ahriman like a natural being.

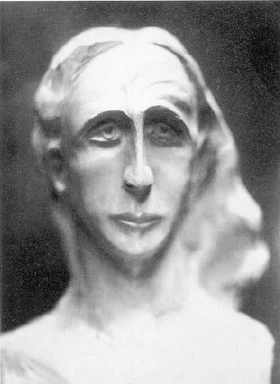

Here (fig. 91) the first model of the Christ figure in profile, as I made it in order to base the wooden group, the sculpture on it.

En face the first model; it is somewhat defective (fig. 92). A model of the Ahriman figure (Fig. 99). A Lucifer figure (Fig. 101), at the side of the wooden figure in the middle.

Another Lucifer (Fig. 98). Above it, carved out of the rock, an elemental being bending its head, as it were, and looking at Christ in union with Lucifer and Ahriman. I have dared to form a face quite asymmetrically, so that it is carved out of the composition. This is usually done in such a way that the composition is made up of the individual figures. Here in the wooden group, the individual figure is always created from the meaning and spirit of the whole composition, hence this asymmetry. It is a completely asymmetrical face, but it has to be like this at the point in the composition where it is in the group.

Here you have the heating and lighting house (Fig. 106) standing on its own, the rear front completely adapted to the machines that are inside. The whole thing is only finished when the smoke comes out of the top. Then these extensions will also be perceived as justified. Artistically, one creates from the form and cannot give an abstract explanation as to why it is this way or that. Some people think they are leaves, others think they are ears. That's not the point, it's the form that matters, which adapts on the one hand to growing out of the boiler house and on the other hand to what happens in the boiler house.

The glass house in which the glass windows have been cut (Fig. 103). These windows are located in the auditorium. They are cut out of monochrome glass panes, i.e. glass panes tinted with a single color. They have a certain history: We had first ordered glass panes from a factory near Paris in the spring of 1914, but the shipment was so delayed that it simply disappeared on the battlefield; we never saw anything of it. We had to buy the panes a second time.

The idea is that the motif is now cut out of the single-colored glass pane using special machines. The pane is then inserted and the work of art is created in the sunlight that passes through. This is connected with the whole idea of building in Dornach. In buildings everywhere else, you have to deal with walls that close off the room. In Dornach you have walls that don't evoke the idea at all: You are closed off. Everything I have now shown you is actually designed to make the walls artistically transparent. The viewer or listener has the feeling in the building that the wall is transparent, artistically transparent through its form, and that he is in contact with the whole wide universe. This is expressed artistically and physically through these glass windows, which are actually only a kind of score, as they are worked out as glass etchings. They become works of art when the sunlight shines through them. In other words, what is inside the building expands into the outer, sunlit nature. The glass cutting had to be done in this studio, which now serves as the building office.

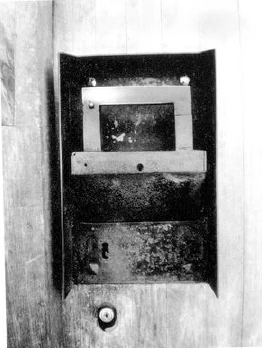

The door to the glass house (Fig. 104). Not even philistine door handles, but completely new door handles (Fig. 105).

[Now] a small sample of the stained glass windows. All kinds of motifs cut out of the single-colored glass pane, but they only make sense to enjoy when you are standing in front of them.

Here (Fig. 112) a pair of people, the feelings of this pair of people carried out in what is around them.

Another window motif, scratched out of the glass (fig. 110). The glasses are not all of the same color, but one color is always followed by another. So that when you enter the building, you can see the different colors from the various windows. The whole room is then illuminated with a symphony of colors, which is artistically perceived as being composed of the most diverse colors. Now, ladies and gentlemen, I have taken the liberty of presenting to you the architectural concept of Dornach in the eighty pictures I have shown you. I have also taken the liberty of explaining to you how this Dornach building concept aims to replace merely static, geometric, symmetrical building with organic building. This had to happen because this spiritual science, as I have represented it here in my lectures, is not merely a one-sided science, but full of life; because it wants to draw fully from the source of world and human life. Therefore, it is not merely a phrase when it is said that religion, art and science and social life should be united with one another, but that the building in its new architectural style simply had to express the same thing out of the whole essence of this spiritual science that is expressed in the spiritual science itself through thoughts or laws.

My esteemed audience, through the willingness of a large number of understanding friends to make sacrifices, we have brought the building so far that last fall we were able to have about thirty experts, people of practice, hold courses in this building, and shorter courses are to be held again at Easter. However, the building is not yet finished. We can only express the hope that we will be able to complete this building, from which a spiritual-scientific movement, which will also bring the social liberation that is necessary for the people of the present and the near future, will emanate. For this, however, it will be particularly necessary to have the international understanding that I described yesterday as the basis for a world school association that works towards the liberation of spiritual life as one member of the tripartite social organism. It will be necessary for this spiritual life to be promoted and supported by the World School Association in an international way.

With regard to the building of Dornach, I know very well what can be objected to from older points of view, from old architectural styles. But if we never dared to do anything new, the development of humanity could not progress. And the impulse to move forward has to do above all with that which wants to emanate from Dornach as anthroposophically oriented spiritual science. Forward in the development of humanity, according to the goals that I indicated yesterday at the end of the lecture.

We know, in that we have also formed this outer shell of anthroposophical spiritual science in the building of Dornach, the Goetheanum, what all can be criticized about this building, what all can be objected to it. We have only one justification for ourselves, which is ultimately decisive for everything new: we must dare to try this new thing. And we always remember what is true: that what is justified will work its way through against all resistance if it is justified. If it is not justified, it will be eliminated and will do little harm to humanity. In the face of all opposition, it will become clear whether the building idea of Dornach is justified as an outer shell for anthroposophically oriented spiritual science. We can only say: we think it is justified, and that is why we dared to do it!

4. Der Baugedanke Von Dornach

Meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden!

Ich muss Sie um Entschuldigung bitten, dass ich in deutscher und nicht in holländischer Sprache sprechen kann; ich werde Ihnen aber eine Anzahl von Lichtbildern zu zeigen haben zur Illustration des heutigen Vortrages, und die werden nicht deutsch, sondern international sprechen.

Dasjenige, was von Dornach aus als anthroposophisch orientierte Geistesbewegung sich in die gegenwärtige Zivilisation hineinstellen will, es wird daran gearbeitet seit zwanzig Jahren etwa. Die anthroposophische Gesellschaft bildete allerdings in den ersten Jahren ein Glied der allgemeinen theosophischen Gesellschaft, aber niemals wurde von mir etwas anderes vorgetragen als dasjenige, was ich auch gegenwärtig zu vertreten habe. Und als, nachdem man diese Anthroposophie innerhalb der theosophischen Gesellschaft eine Weile geduldet hatte, sie dann als zu ketzerisch befunden wurde und gewissermaßen hinausbefördert wurde, da wurde dann die Anthroposophische Gesellschaft als eine selbstständige Gesellschaft begründet.

Die anthroposophische Bewegung will durchaus rechnen mit der wissenschaftlichen Gesinnung der gegenwärtigen zivilisierten Welt, Sie will durchaus nicht irgendetwas Sektiererisches oder dergleichen sein, sondern sie will befruchtend wirken in ernster Weise auf die verschiedenen Wissenschaften in unserer Zeit, auf das religiöse Bewusstsein und auch auf das künstlerische und soziale Leben der Gegenwart.

Schon etwa um das Jahr 1909 war diese anthroposophische Bewegung innerhalb Mitteleuropas so weit angewachsen, dass es unmöglich war, für ihre Arbeit ohne ein eigenes Gebäude auszukommen, und so entstand dazumal bei einer Reihe langjähriger Mitglieder der Gedanke, der Anthroposophie einen eigenen Bau aufzuführen. Und als an mich die Absicht herantrat, einen solchen Bau aufzuführen, ergab sich sogleich aus dem Wesen der anthroposophischen Arbeit heraus ein ganz bestimmter Impuls. Wenn man sonst aus irgendeiner geistig genannten Bewegung in die Notwendigkeit versetzt worden wäre, ein eigenes Gebäude aufzuführen, man würde zu irgendeinem Baumeister gegangen sein und würde von ihm aufgeführt bekommen haben einen Renaissancebau oder einen gotischen Bau oder einen griechischen Bau oder dergleichen.

In einer solchen äußerlichen Weise vorzugehen wäre unmöglich gewesen für anthroposophisch orientierte Geisteswissenschaft. Denn diese ist nicht etwas, was in bloß theoretischer Weise eine Kopfkultur verbreiten will, sondern anthroposophisch orientierte Geisteswissenschaft geht aus dem Quell des vollen Menschentums hervor. Wie sie aus diesem Quell des vollen Menschentums hervorgeht, das habe ich mir erlaubt, in den zwei vorangehenden Vorträgen hier in diesem Saale auseinanderzusetzen. Deshalb aber, weil das so ist, weil Anthroposophie nicht einseitig bloß theoretische Wissenschaft ist, sondern weil sie etwas ist für das ganze ausgebreitete menschliche Leben in all seinen Betätigungsformen, deshalb musste sich auch diese anthroposophische Bewegung einen eigenen Baustil aus ihren Quellen heraus schaffen in dem Moment, wo an sie die Notwendigkeit herantrat, sich ein eigenes Gebäude aufzuführen. Und solch ein Gebäude aufzuführen ist uns gelungen. Es ist bisher noch nicht fertig, aber es ist doch schon so weit fertig, dass im letzten Herbst Kurse darin gehalten werden konnten und wiederum zu Ostern gehalten werden sollen. Es ist uns gelungen, ein solches Gebäude aufzuführen auf dem Dornacher Hügel in der Nähe von Basel in der Schweiz.

Ich sagte, aus denselben Quellen, aus denen die Geisteswissenschaft herausgeboren ist, ist auch der Stil dieses Goetheanum herausgestaltet, der Versuch eines neuen Baustils, selbstverständlich mit all den Gefahren, mit all den Unzulänglichkeiten, mit denen solch ein erster Versuch eines neuen Stils verbunden sein muss. Wirklich aus den Quellen des Seins, nicht aus Gedanken oder bloßen experimentellen und gedanklich ausgedeuteten Untersuchungen heraus entsteht Anthroposophie, aus den Quellen des Daseins selber. Daher muss sie sich verbinden bei all ihrem Schaffen mit den Schaffenskräften, die zum Beispiel in der Natur selber wirksam sind, denn die letzten Schaffenskräfte in der Natur sind ja, wie ich ausgeführt habe in den vorangehenden Vorträgen, selber geistiger Art.

Ich darf vielleicht einen Vergleich anwenden. Nehmen Sie eine Nuss. Sie hat den Nusskern; dieser Nusskern ist in einer gesetzmäßigen Weise gestaltet. Es gibt aber auch die Nussschale; sie könnte nicht anders sein, wie sie ist, nachdem die Nuss so ist, wie sie ist. Dieselbe Kraft, die den Nusskern gestaltet, sie gestaltet in eindeutiger Weise auch die Nussschale. Genau ebenso naturgesetzlich, wie der Nusskern gestaltet ist, ist auch die Nussschale gestaltet.

In Dornach wird anthroposophische Geisteswissenschaft vom Podium aus gelehrt. Es werden die Ergebnisse anthroposophischer Geisteswissenschaft erforscht. Es werden künstlerische Darstellungen geboten, welche ein äußerer Ausdruck sind - künstlerisch, nicht symbolisch oder strohern allegorisch, sondern künstlerisch — desselben, wovon Geisteswissenschaft selber der Ausdruck ist. Daher muss um alles das herum, gewissermaßen um den Nusskern herum, auch die Schale gestaltet werden, die genau aus denselben Gesetzen heraus [gestaltet] ist.

Daher ist in Dornach eine Architektur gepflogen worden, die aus demselben Sinn, aus demselben Geist heraus [gestaltet] ist wie anthroposophische Geisteswissenschaft selber. Es wird dort gebildhauert genau aus demselben Geist heraus, gemalt aus demselben Geist heraus. Wenn irgendjemand auf dem Podium steht und in Ideen spricht, so ist das nur eine andere Ausdrucksform desjenigen, was die Säulen sprechen, was die Malereien an den Wänden sprechen, was die plastischen Darstellungen sprechen. Alles ist, wenn ich mich so ausdrücken darf, aus einem Guss heraus.

Die Menschen haben so große Angst, dass auf diese Weise nichts Künstlerisches zustande käme, sondern nur etwas Symbolisches oder Allegorisches. Nun, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, in Dornach gibt es kein einziges Symbolum, keine einzige Allegorie, sondern alles ist versucht, in künstlerischen Formen zu geben. Nicht will man die Ideen, die vorgetragen werden, durch Bilder irgendwie verkörpern, das wäre unkünstlerisch. Sondern das eine spirituelle Leben, das zugrunde liegt, man kann es einmal gestalten künstlerisch, man kann es das andere Mal gestalten ideell, in Gedanken, wissenschaftlich. Nicht ist die Kunst in Dornach ein didaktischer Ausdruck etwa für eine Wissenschaft, sondern sie ist die eine Darstellung, und die Wissenschaft ist die andere Darstellung desselben großen, spirituell Unbekannten, aus dem in der anthroposophischen Geisteswissenschaft alles geschöpft wird, was sie der Menschheit geben will.

Dementsprechend musste schon die ganze äußere Gestaltung des Dornacher Baues sein. Derjenige, der sich diesen Dornacher Bau ansieht, der wird sehen einen Doppelkuppelbau, nebeneinander stehen zwei Kreiszylinder, die aber ineinandergreifen, darüber zwei halbkugelförmige Kuppeln, welche im Kreissegment durch eine etwas schwierige mechanische Konstruktion ineinandergefügt sind. Da in Dornach dasjenige, was durch Geisteswissenschaft erforscht werden kann, an die Welt herangebracht werden soll, so muss das sich schon im Bau darleben. Der kleine Kuppelbau ist eine Art Bühne; in ihm werden dargestellt Mysterienspiele und dergleichen. Auch Eurythmie wird aufgeführt, aber projektiert ist noch vieles andere. Zwischen dem kleinen und dem großen Kuppelraum steht das Podium für den Redner. Der große Kuppelraum ist der Zuschauerraum oder Zuhörerraum für nahezu tausend Personen. In diesem Doppelkuppelbau drückt sich eben aus die Tatsache: Anthroposophische Geisteswissenschaft hat das an die Welt der Gegenwart und der Zukunft in geistiger, in allgemein menschlicher, in sozialer Beziehung zu sagen, was ich in den beiden vorangehenden Vorträgen mir erlaubte auseinanderzusetzen.

Wenn man von Westen herankommend sich dem Bau nähert [und] dem Hauptportal, das nach Westen orientiert ist, entgegenkommt, so bietet sich zunächst der folgende Anblick dar (Abb. 5). Der Bau besteht unten aus Beton; oben ist eine Terrasse, die in einer stilisierten Rundung um den Bau herumführt. Auf diesem Beton-Grundbau steht dieser Holzbau. Die Kuppeln sind eingedeckt mit jenem wunderbaren, besonders im Sonnenlicht wunderbar wirkenden nordischen Schiefer, der in den Schieferbrüchen zu finden ist, die man sieht auf der Fahrt von Kristiania nach Bergen, aus den Vossischen Schieferbrüchen. Dieser Schiefer fügt sich in wunderbarer Weise in den Hauptgedanken von Dornach herein. Beton und Holz, beide sind so bearbeitet, dass ein Baustil herauskommt, welcher etwa charakterisiert werden kann als die Überführung der bisher existenten geometrischen, symmetrischen, mechanischen, statischen, dynamischen Baustile in einen organischen Baustil. Nicht als ob irgendeine organische Form nachgeahmt worden wäre in den Bauformen von Dornach, das ist nicht der Fall, sondern es wurde versucht von mir, im Sinne der Goethe’schen Metamorphosenlehre sich ganz einzuleben in das naturgemäße Schaffen der organischen Formen und herauszubekommen organische Formen, die dann, indem man sie metamorphosiert, ein Ganzes in dem Dornacher Bau geben konnten; organische Formen, die so sind, dass jede einzelne Form an dem Orte sein muss, wo sie eben ist.

Vergegenwärtigen Sie sich einmal das Wesen der organischen Formen. Denken Sie an irgendetwas scheinbar recht Unbedeutendes in der organischen Form des menschlichen Organismus: an ein Ohrläppchen. Sie werden sich sagen müssen: Dieses Ohrläppchen, an der Stelle, wo es ist, könnte es nicht anders sein, wie es ist, wenn der ganze Organismus so ist, wie er sich eben offenbart. Das Kleinste und das Größte in einem organischen Zusammenhang hat an seinem Ort des Organismus seine ganz bestimmte Form. Das ist übergegangen in den Baugedanken von Dornach.

Ich weiß sehr gut, wie viel von den Gesichtspunkten der alten Baustile aus gegen dieses organische Prinzip des Bauens einzuwenden ist. Aber es ist einmal im Baugedanken von Dornach dieser organische Baustil geprägt worden. Man mag ihn ablehnen von alten Gesichtspunkten aus, aber man hat ja schließlich alles Neue von alten Gesichtspunkten aus abgelehnt. Jedenfalls aber, wenn man sich überhaupt befreunden kann mit der Überführung der statisch-dynamischen, geometrischen Bauformen in organische, dann wird man finden, dass alle Übergänge von einer organischen Formung in eine andere - nicht organische [Natur-] Formen, denn es ist nichts naturalistisch nachgeahmt - mit derselben inneren Gesetzmäßigkeit erlebt [werden können], wie, sagen wir, das Pflanzenblatt, das unten am Stiel ist, sich metamorphosiert, wenn es weiter oben am Stiel auftritt, immer dieselbe Form [ist], aber mit der größten Mannigfaltigkeit abwechselnd.

So finden Sie in Dornach gewissermaßen in den Baugedanken hereingetragen überall bestimmte organische Formen, wie sie hier aus dem Holz herausgeschnitzt sind, wie sie hier bei den Eingangssäulen als Kapitelle auftreten. Hier an den Seitenfenstern (Abb. 4, 12) sehen Sie dasselbe Motiv, an den Fenstern des Seitentraktes (Abb. 13) auch, scheinbar nicht mehr ähnlich, aber dennoch dasselbe metamorphosiert, wie im Blumenblatt auch das Motiv des grünen Laubblattes wieder auftritt.

Wenn man den Bau von innen und von außen besieht, so kann man den Eindruck haben: Wenn irgendein Motiv in der Nähe des Tores ist, da ist es anders gearbeitet, sodass man sieht, gegen das Tor hin hat das Motiv weniger zu tragen, während es sich entgegenstemmen muss da, wo es der ganzen Schwere des Baues entgegenliegt. Das alles, wie es berücksichtigt ist in der Natur bei der Ausbildung der Knochen und Muskelformen, das ist im Baugedanken von Dornach durchaus durchgeführt. Sehen Sie sich einmal die Knochenform innerhalb der Kniebildung an, sie ist in wunderbar naturgenialischer Weise so gestaltet, dass gewisse Knochen, die Grundlageknochen bilden, dasjenige, was auf ihnen liegt, tragen. Sie sind ausgeweitet und eingezogen an der rechten Stelle. Das Hinein-sich-Fühlen in die Formen der organischen Bildung, des Tragens, des Lastens, das war notwendig, um den Bau von Dornach auszuführen.

Hier (Abb. 5) geht man hinein. Hier ist ein Raum zum Ablegen der Kleider, hier eine Treppe innen, durch die man hinaufschreitet. Man kann um diese Terrasse herumgehen und hat zu gleicher Zeit die Fernsicht weit über die Lande, den schweizerischen Jura.

Dasselbe Bild, etwas verschoben und nähergekommen (Abb. 6).

Hier (Abb. 7) sehen Sie den Bau, wie er sich einem präsentiert von Südwesten her kommend. Hier der Umgang, unten der Betonbau.

Der Bau, wie man ihn sieht, wenn man sich nähert von Norden aus (Abb. 1), sodass man vor sich hat hier die große Kuppel, [hier] die kleine Kuppel. Hier sind die beiden Kuppeln ineinandergefügt.

Von einem Punkt im Norden aus der Bau (Abb. 2). Hier sehen Sie ein merkwürdiges Gebilde. Das ist dasjenige, was am meisten getadelt wird. Es ist dasjenige Gebäude, welches in der Nähe des Baues steht. Ich bin davon ausgegangen, die Beleuchtungsmaschinen und Beheizungsmaschinen wie den Nusskern zu betrachten, und darüber eine Schale zu konstruieren, aus dem künstlerisch ja außerordentlich schwer bearbeitbaren Betonmaterial. Diejenigen, die diesen Bau heute noch tadeln, die bedenken nicht, was da stehen würde, wenn man sich nicht bemüht hätte, aus dem künstlerisch so spröden Betonmaterial heraus etwas künstlerisch zu gestalten: es würde ein roter Schornstein da stehen. Ich möchte die Leute fragen, ob das schöner wäre als dasjenige, was gewiss als erster Versuch, aus Beton heraus etwas zu stilisieren, manche Mängel hat, aber doch ein erster Versuch ist, etwas Künstlerisches in diesen Dingen auch zu gestalten.

Hier (Abb. 3) der Bau von Nordosten her gesehen. Hier steht ein Haus, das schon gestanden hat, als wir den Baugrund geschenkt bekamen. Ein Haus, von dem wir sehr hoffen, dass wir es einmal erwerben können. Sie können sich denken, zu welchem Zweck wir es gern erwerben würden; es stört uns natürlich den ganzen Aspekt des Baues.

Hier die Ineinanderfügung der Kuppeln (Abb. 17). Hier der Haupttrakt, hier der Haupteingang (Abb. 10).

Hier ist das Atelier, in dem die Glasfenster gemacht worden sind (Abb. 103). Es ist als Atelier zum Schleifen der Glasfenster aufgeführt worden.

Dahinter wieder das Heizhaus (Abb. 106, 107). In einem Nachbardorf, in Arlesheim, steht eine besonders geschmacklos gebaute Kirche. Ich habe nichts dagegen zu sagen, aber sie ist ehrlich geschmacklos. Dennoch hat es der Schweizerische Verband zur Verschönerung der schweizerischen Bauwerke fertig gebracht zu sagen, dass dieser [unser] Bau diese Gegend der Schweiz verunziere: man sollte sich nur einmal die schöne Arlesheimer Kirche dagegen anschauen.

Der Grundriss (Abb. 20). Haupteingang, Orgelraum, Zuschauerraum. Hier steht das Rednerpult. Der Bühnenraum. Hier sind die zwei Seitentrakte mit den einzelnen Räumen für die darstellenden Schauspieler und sonstigen Künstler. Hier sehen Sie sieben Säulen zu beiden Seiten. Hier in der Rundung sechs Säulen. Diese sieben Säulen sind nicht aus irgendeinem mystischen Drang in der Siebenzahl gebildet, sondern rein aus der künstlerischen Empfindung heraus. Wie die Violine vier Saiten hat, so hat die künstlerische Empfindung hier aus inneren Gründen ergeben, dass man eine gewisse künstlerische Entwicklung und wiederum einen künstlerischen Abschluss herausbekommt, wenn man gerade sieben Motive entwickelt. Bei diesen Säulen ist das Wagnis unternommen worden, nicht etwa die Kapitell- und Architravmotive wie Wiederholungen zu gestalten, sondern in lebendiger Entwicklung. Wenn man hereinkommt vom Westportal, so trifft man die zwei ersten Säulen. Die sind allerdings symmetrisch gestaltet. Wenn man aber von der ersten zur zweiten Säule fortschreitet, dann ist das Kapitell der zweiten Säule, der Sockel, der Architrav über der zweiten Säule so gestaltet, wie es sich organisch gestalten muss. Es ist so gestaltet, dass man sich hineinleben musste in das Schöpfen und Schaffen der Naturkräfte, wenn man künstlerisch herausgestalten wollte das zweite Säulenmotiv aus dem ersten, das dritte wiederum aus dem zweiten und so weiter, bis ein gewisser Abschluss im siebenten Säulenmotiv erreicht worden ist.

Viele Besucher kommen nach Dornach und fragen: Was bedeutet das einzelne Kapitel? Das kann man Künstlerischem gegenüber überhaupt nicht fragen. Das Wesentliche ist, dass künstlerisch-formhaft hervorgehe die eine Säule aus der anderen Säule. Während man es im statischen Baustil eigentlich nur mit Symmetrie zu tun hat, mit Wiederholungen desselben Motivs, hat man es hier mit einer lebendigen Evolution von der ersten zur siebenten Säule zu tun. Ich werde dann die Säulen später zeigen, dann können Sie dieses sehen.

Durchschnitt durch den Bau (Abb. 21).

Ursprüngliches Modell, in der Mitte senkrecht durchschnitten (Abb. 22). Ich habe ursprünglich den ganzen Bau als Modell auszuarbeiten gehabt, sodass sogar der Bauplan, Grundriss und Aufriss, wie sie denn zugrunde gelegt worden sind, nach diesem Modell geformt worden sind. Dieses ganze Modell ist eben die Verkörperung des Baugedankens von Dornach, ist durchempfunden, wie die Geisteswissenschaft selbst durchempfunden ist, ist gewissermaßen ein anderer Ausdruck für dasjenige, wofür der eine Ausdruck eben die Geisteswissenschaft selber ist.

Ganz nahe des Haupteingangs, des Hauptportals im Westen (Abb. 15). Die Bilder sind zu einer Zeit aufgenommen, wo der Bau noch im vollen Gang war.

Ein Stück anschließend an den Haupteingang (Abb. 12). Hier dasjenige, was die Treppe zum Hinaufgehen enthält. Hier ein Haus in der Nähe. Dieses Haus ist auf ganz besondere Weise zustande gekommen. Wir haben ja den ganzen Bau aufgeführt durch das Verständnis unserer anthroposophischen Freunde. Dass gerade der Dornacher Hügel verwendet worden ist, um diesen Bau aufzuführen, das erklärt sich daraus, dass ein Freund in Basel, in der Nähe von Basel zum Bau eines Sommerhauses für sich diesen Baugrund vor langer Zeit schon angekauft hat; er hat uns dann diesen Grund geschenkt. Da konnten wir dann den Bau aufführen. Außerdem wollte der Freund dann sein Haus auch hier haben. Und da trat an mich die Aufgabe heran - verschiedene Bedingungen ergeben die Notwendigkeit -, aus Betonmaterial heraus nun ein Haus, ein Familienwohnhaus mit fünfzehn Zimmern ungefähr zu stilisieren. Es ist ein gewisses Wagnis gewesen. Es sind auch durchaus noch Mängel an diesem Haus, das aus dem Künstlerischen des spröden Betonmaterials herausgeformt ist. Aber solche Dinge müssen eben einmal zum ersten Mal gemacht werden.

Ein Seitentrakt (Abb. 17). Diese zwei Seitentrakte sind wie ein Querbalken eingefügt. Hier das Hauptmotiv wiederum metamorphosiert. Überall dasselbe und doch wiederum etwas anderes, könnte man sagen, ist in den Bauformen enthalten.

Vordere Fassade eines Seitentrakts (Abb. 14). Hier wieder das Motiv, welches am Haupteingang ist, sehr verbreitert, mit reichem Material ausgestaltet, hier einmal sparsamer ausgestaltet in derselben Metamorphose. Es ist überall ein gewisses Gesetz der Symmetrie eingehalten, die sich aber zusammen angewendet findet mit Asymmetrie. Diese Asymmetrie gibt dem Bau eine künstlerisch wohltuende Wirkung und eine große Abwechslung.

Etwas größer genommen das Motiv der Fassade eines solchen Seitentraktes (Abb. 11).

Wir treten durch den Betoneingang im Westen herein, stellen Sie sich vor (Abb. 23). Dann kommen wir zunächst hier zur Treppe, die hinaufführt. Hier würde der Raum sein, wo man die Kleider ablegt. Dann geht man nach vorne, hier geht es in den Zuschauerraum hinein. Hier habe ich gewagt, die Säulenform organisch zu gestalten.

[Dann] zum Beispiel diese Form hier (Abb. 24): Es sind drei aufeinander senkrecht stehende Motive. Wie ist diese Form entstanden? Nicht durch irgendein Ausphilosophieren, sondern rein aus der Empfindung heraus. Man kann sich sagen: Wer durch das Hauptportal zunächst eingetreten ist, dann in den Zuschauerraum kommen will, muss in einer gewissen Weise sich demgegenüber, was er in Dornach vernehmen will aus anthroposophisch orientierter Geistesschau heraus, zu dem Gedanken und zur Empfindung hinbewegen können: Hier darfst Du zur Sicherheit Deiner Seele, zur Gewinnung eines festen Haltes in deinem Innern eintreten. Hier darfst Du so eintreten, dass keinerlei Lebensillusionen dich betören sollen; dass kein irgendwie wankend Werden über Dich kommen soll. Das ist empfindungsgemäss in diesem Motiv hier zum Ausdruck gekommen.

Dann sehen Sie hier eine Säule, welche die Treppe trägt (Abb. 25). Das Treppenmotiv selber ist so gestaltet, dass es organisch sich dem Bau entgegenstemmt, hier dem Ausgang entgegenwirkt. Hier getragen von einer Säule, die nicht etwa in naturalistischer Art organisch Motive nachahmt, aber die ebenso organisch gestaltet ist, wie eben die Formen der Lebewesen der Natur aus den schöpferischen Kräften der Natur heraus. Wie diese Säule aufsteht, auf der einen Seite etwas trägt, wo das zu Tragende leichter ist, wie es sich entgegenstemmt hier dieser Seite, wo die Hauptlast des Baues liegt, das ist in den kleinsten Dingen so zum Ausdruck gebracht, wie eben in der Ohrläppchenform die Zusammengehörigkeit zum ganzen menschlichen Organismus ausgedrückt ist. Jede Form in Dornach muss an ihrem Ort als eine Notwendigkeit empfunden werden.

Hier (Abb. 26) ein Motiv, welches ich in den verschiedenen Metamorphosen durchgeführt habe. Hier ist es aus Beton geformt, im oberen Trakt aus Holz. Es ist ein Vorsetzer für einen Heizkörper. Es ist, wie gesagt, in Dornach so, dass die einzelnen Formen durchaus metamorphosisch auseinander hervorgehen, und man nicht irgendwie abstrakte, bloß der Uti kunst angemessene Formen hat, sondern alles streng künstlerisch organisch durchgeführt ist.

Hier (Abb. 27) sehen Sie dann den Raum, in den man kommt, wenn man über die eben ausgeführte Treppe hinaufkommt. Das ist ein Holzbau. Hier eine Säule, welche die Decke trägt. Das alles, was sich unmittelbar anschließt als Innenraum, ist ausgeführt in Handarbeit von einer großen Zahl unserer Freunde. Es muss immer wiederum betont werden, dass eine große Anzahl von Freunden sich in Dornach durch viele Jahre eingefunden haben, die alle diese einzelnen plastischen Formen, die ihnen im Modell gegeben worden sind, mit der Hand herausgearbeitet haben. Gewissermaßen ist der ganze Holzbau die Handarbeit der anthroposophischen Freunde. Und das ist etwas, was zu gleicher Zeit als mustergültig hat wirken können für die liebevolle Zusammenarbeit einer Menschengruppe.

Wenn man nun eintritt und im Zuschauerraum nach rückwärts schaut, sieht man hier die Orgelempore. Es ist dies das Modell (Abb. 30). Es ist so gedacht, dass man nicht die Orgel in eine Höhlung hineinstellt, sondern dass die Orgel genommen worden ist und die Architektur danach geformt worden ist. Es sind dann bei der Ausarbeitung noch Ergänzungsmotive hinzugefügt worden.

Hier der Innenraum (Abb. 29). Wenn Sie in den Innenraum eintreten, so sehen Sie hier den Orgelvorbau, wo die Sänger stehen. Hier die drei ersten Säulen. Das Bild der Säulenformung werde ich gleich auseinandersetzen. Über den Säulen die Architrave, welche ebenfalls fortschreitende Motive zeigen.

Hier die Orgelempore (Abb. 28).

Hier der Raum über der Orgel, aus Holz heraus plastisch gestaltet (Abb. 33). Bitte sehen Sie sich das Kapitel an. Es ist aus einfachen Formen zusammengesetzt. Wir werden den Übergang machen zu den immer nächsten Kapitell- und Architravformen. Es ist so, dass man sich nicht etwas Ausgedachtes zu denken hat, wie das eine Kapitell aus dem anderen hervorgeht, sondern es ist einfach so empfunden wie ein Blatt am Stängel einer Pflanze, aus dem nun andere metamorphosisch hervorgehen. So sind hier die nächsten Motive immer ganz empfindungsgemäß aus den vorhergehenden herausgebildet.

Hier haben Sie das einfache Kapitellmotiv der ersten Säule (Abb. 34).

Die erste Säule und die zweite Säule (Abb. 35). Wenn Sie sich das einfache Motiv von oben nach unten, von unten nach oben denken, so können Sie sich empfindungsgemäß denken, wie es wächst. Die Tropfen von oben wachsen in diese Form hinein, und von unten heraus wachsen die Formen so, dass sie ihnen entgegenkommen in komplizierteren Formen. Ebenso ist es mit den Architravmotiven.

Zweites Säulenmotiv (Abb. 36): schon komplizierter.

Zweite und dritte Säule zusammen (Abb. 37): Wiederum organisch metamorphosisch bekommt man aus der zweiten Säule die dritte Säule.

Die dritte Säule für sich (Abb. 38).

Dritte und vierte Säule zusammen (Abb. 39). Das, was hier noch einfacher ist, komplizierter geworden. Dabei macht man ganz besondere Entdeckungen. Ich habe einfach nach der künstlerischen Empfindung ein Motiv aus dem anderen hervorgehen lassen. Dabei hat sich mir gezeigt, dass man durch dieses künstlerische Vorgehen erst das Wesen der Evolution in der Natur richtig verstehen kann. Man stellt sich ja gewöhnlich vor, dass in einer Entwicklungsströmung die ersten Formen die einfacheren seien, die dann immer komplizierter und komplizierter werden. Das ist nicht der Fall. Wenn man künstlerisch arbeitet, dass man das eine aus dem anderen hervorgehen lässt, dann kommt man zu einer Gestaltung des Einfacheren ins Kompliziertere, aber wenn die Komplikation auf einer bestimmten Höhe angelangt ist, dann werden die Dinge zwar harmonischer, aber wieder einfacher. Sodass die Evolution sich so darstellt: vom Einfachen zum Komplizierteren und dann wiederum zur Vereinfachung. Diese Entdeckung überrascht einen zunächst. Man gestaltet so etwas aus dem rein Künstlerischen heraus und findet dann, dass es eigentlich dem künstlerischen Schaffen der Natur voll entspricht.

Man betrachte einmal das menschliche Auge: Es ist das vollkommenste, aber nicht das komplizierteste. Gewisse Organe, welche niedrigere Wesen haben, der Fächer im Auge, der Schwertfortsatz, sie sind vom menschlichen Auge aufgesogen. Auf das kommt man von selbst, wenn man rein künstlerisch formt.

Ebenso hat sich mir etwas sehr Merkwürdiges ergeben. Ich sagte, sieben Säulen musste ich formen, wirklich nicht aus einem mystischen Hang. Es stellte sich die siebente Säule als Abschluss dar; man konnte nicht mehr weiter, die Motive hatten sich erfüllt. Aber nachher entdeckte ich: Wenn ich die konvexe Form der siebenten Säule nahm und etwas künstlerisch umgestaltete, so ging sie in die konkave, die eingehöhlte Form der ersten Säule gerade hinein. Das habe ich nicht gesucht. So war es ebenso mit der sechsten und der zweiten Säule und ebenso mit der dritten und fünften Säule. Das entdeckte ich als etwas, das sich aus dem Arbeiten im Sinne einer Evolution ganz von selbst für die Kapitelle und für die Sockelfiguren ergab. Das ist nicht gesucht. Auch in der Natur selbst stellen sich solche überraschenden Formzusammenhänge ein. Man bekommt dann, wenn man künstlerisch schafft, diese Dinge, die einem da aus den einzelnen Formen entgegentreten, und man kommt zu einer tiefen Achtung des geheimnisvollen Waltens und Webens erstens in der Natur, zweitens aber in der Formenwelt selber, die man imaginativ-künstlerisch und schauend durchdringen kann.

Eine Säule für sich allein, verhältnismäßig kompliziert geworden (Abb. 42). Sie werden aber sehen, indem dieses Motiv so gedacht ist, dass es wächst von oben nach unten, von unten nach oben, so kommt etwas heraus, was ich nun auch wiederum nicht angestrebt habe; aber wenn die Leute es sich anschauen, werden sie sagen: Der hat den Merkurstab gebildet. Das habe ich nicht bilden wollen, aber es kam so zum Vorschein.

Es breitet sich aus, wächst, so entsteht dieses komplizierte Motiv (Abb. 41), dann werden die Motive einfacher.

Hier sehen Sie dieses Motiv (Abb. 43). Jetzt konnte ich nicht in der Komplikation weiter. Indem ich mir das wachsend dachte und es wachsend empfand, entstand dieses einfachere Motiv.

Die beiden letzten Säulen mit ihren darüber liegenden Architraven (Abb. 45). Die Säule unmittelbar vor dem Bühneneingang (Abb. 46).

Auf diese Weise sehen Sie also, wie die einzelnen Kapitelle auseinander entstanden sind, überhaupt die ganzen Säulenmotive in ihrer Evolution künstlerisch entstanden sind.

Hier sind wir vor einem Sockel (Abb. 48). Ich habe einzeln diese Sockel wiederum der Reihe nach vorführen wollen, wie sie sich ebenso auseinanderentwickeln wie die Kapitelle.

Alles Sockel (Abb. 48-54). Zuerst wieder komplizierter werdend, dann wieder einfacher.

Hier blicken Sie von dem Zuschauerraum hinein in den Bühnenraum (Abb. 57). Hier sehen Sie das Innere der Bühnenkuppel ausgemalt. Hier die Architrave über den Säulen des Zuschauerraums. Hier schließt der Zuschauerraum vor dem Bühnenraum ab. Noch in Arbeit begriffen der Spalt, der zusammenschließt den Zuschauerraum mit dem Bühnenraum (Abb. 56).

Wiederum der Blick vom Zuschauerraum, dessen letzte Säulen Sie sehen, in den Bühnenraum hinein (Abb. 55). Hier der ausgemalte Bühnenkuppelraum. In Bezug auf die Malerei der beiden Kuppeln kann ich Ihnen allerdings nicht solche Bilder geben beziehungsweise nicht so deutlich sprechende Bilder geben wie über das andere. Denn in Bezug auf die Ausmalung des Dornacher Baus ist durchaus, wenigstens im kleinen Kuppelraum, ganz ernstlich angestrebt worden und befolgt worden, was ich bezeichnet habe einmal als das Wesen der neueren Malerei. Es muss alles dasjenige, was malerisch geschaffen wird, aus der Farbe herausgeholt werden.

Die Farbenwelt ist eine Welt für sich. Derjenige, der sich einlebt in die Farbenwelt, der lernt erkennen das Schöpferische jeder einzelnen Farbe; er lernt erkennen das Schöpferische, das in der Farbenharmonik liegt. Derjenige, der weiß, wie Rot auf die menschliche Empfindung wirkt, wie Rot von innen aus spricht, wer weiß, Blau wirkt, formend, gestaltend, der kommt dazu, aus der Farbengebung heraus die malerische Welt zu gestalten

So ungefähr versuchte man zu schaffen beim Ausmalen des kleinen Kuppelraumes in Dornach. Das Wesentliche ist ja immer, wenn ich mich jetzt so ausdrücken darf, der Farbfleck an einer bestimmten Stelle. Trotzdem Figurales herausgeboren ist aus der Farbe, ist alles ursprünglich aus der Farbe heraus gedacht. Hell, Dunkel und Farben sind eigentlich das Einzige, was berechtigt ist, wenn man malerisch mit Hilfe der Fläche etwas darstellt, das Zeichnerische ist eigentlich eine Verlogenheit. Nehmen Sie die Horizontlinie: oben der blaue Himmel, unten das grünliche Meer. Malen Sie das so, dann ergibt sich der Horizont als das Geschöpf der Farbenbegegnung von selber. Und so ist es mit allen Linien in der wirklichen Malerei. Die Form ist bei der Malerei das Werk der Farbe. Das ist dasjenige, was in Dornach durchzuführen versucht wurde.

Da (Abb. 64) sehen Sie zunächst das, was unter dem Kuppelbau ist, das Architrav-Motiv, unmittelbar über der Gruppe, die im Osten des Baues gewissermaßen als der plastische Mittelpunkt dieses Baues hingestellt werden soll. Ein Motiv aus dem kleinen Kuppelraum (Abb. 66). Ich bitte, diese Motive in derselben Weise zu beurteilen wie diejenigen des großen Kuppelraumes, nur dass gedacht sind sechs Säulen an beiden Seiten; dadürch sind die ganzen Formüngen und Gestaltungen «ben andere.

Ein Kapitellmotiv des kleinen Kuppelraums (Abb. 58-63).

Das erste in der Ausmalung des kleinen Kuppelraumes, wenn man in denselben hineinkommt (Abb. 73). Natürlich, eine richtige Empfindung wird man von dem, was ich jetzt zeigen kann, erst haben, wenn man diese [fotografische] Nachbildung in ihren Mängeln empfindet, wenn man sich sagt: Was ist das eigentlich? Da müsste Farbe sein! Es ist natürlich auch Farbe, alles ist aus der Farbe herausgeholt.

Hier ein Kind, welches entgegenfliegt einer Art Faustfigur (Abb. 69). Das Kind ist rotgelb, die Faustfigur in Blau.

Hier Faust (Abb. 70), [hier] das Kind (Abb. 69). Diese Faustfigur stellt etwa dar die Zivilisation des fünfzehnten, sechzehnten Jahrhunderts, in der wir ja eigentlich noch immer alle drinnenstecken. Dasjenige allerdings, was sich von jener Zivilisation in der äußeren theoretischen Wissenschaft ausgestaltet, das ist im Grunde genommen nur Oberfläche. Derjenige, der sich in die Weltanschauung, die durch die neuere Naturwissenschaft heraufgekommen ist, mit seinem ganzen Menschen einlebt, der empfindet stark auf der einen Seite den Tod, auf der anderen Seite das knospende, keimende Leben. Diese zwei polarischen Gegensätze treten gerade aus der Naturanschauung der Gegenwart einem entgegen. Nehmen Sie nur das Folgende: So, wie wir die Natur beschreiben, verwenden wir dazu Begriffe, die im Grunde genommen von dem Toten, dem Mineralischen hergenommen sind. Unsere Naturforscher sehen ein Ideal darin, auch das pflanzliche, das tierische Leben nach dem Muster des Mineralischen zu denken, vielleicht sogar experimentell in diese Richtung arbeiten zu können. Der Todesgedanke tritt einem da sehr stark entgegen (Abb. 71). Demjenigen steht aber gegenüber, wenn wir in unser Selbstbewusstsein hineinforschen, dasjenige Leben, das polarisch entgegengesetzt ist dem Tod, das wir insbesondere empfinden, wenn wir unbeeinflusst von Erkenntnis das Kindesleben auf uns wirken lassen. Es ist durchaus der Empfindung entsprechend, dass hier eine Faustfigur auftritt, aus dem Blau heraus gemalt.

[Hier] das einzige Wort, das Sie im ganzen Bau finden: ICH (Abb. 72).

In dieser Zeit, in der diese Faustfigur in die moderne Zivilisation eintritt, lernt man das Ich als den abstrakten Inhalt des Selbstbewusstseins eigentlich erst so recht kennen. Sie wissen ja, ältere Sprachen haben noch in dem Verb das Ich darinnen. Herausgeschält, für sich hingestellt wird das Ich in diesem Zeitalter, wenn zu gleicher Zeit diese Kultur auftritt, deren politische Gegensätze ich soeben hingestellt habe. Das tritt einem als erstes Motiv in der Malerei der kleinen Kuppel entgegen.

Hier der Faust (Abb. 70), hier der Tod (Abb. 71) als der Gegensatz zu dem Kinde. Gerade das modernste Erkenntnis- und Geistesleben soll in dieses Motiv, aber aus der Farbe heraus, zum Vorschein kommen, aus dem gelbrötlichen Ton des Kindes, dem blauen Ton des Faust, dem bräunlich-schwärzlichen Ton dieses Skelettes.

Eine engelartige Figur über dem Faust (Abb. 74). Gewissermaßen ist überall unten eine Gestalt, die das mehr Menschliche darstellt, darüber eine Geistgestalt, der Inspirator, die inspirierende Gestalt.

Hier (Abb. 75) ein Bild herausgeboren aus der Empfindung der griechischen Kultur, also mehr in der Zeit zurückliegend. Die Faustfigur ist herausempfunden aus der neuzeitlichen Kultur, in der wir immer noch drinnenstehen. Hier eine Art Pallas-Athene-Figur, aus der griechischen Kultur empfunden, darüber die inspirierende Figur (Abb. 76).