The Building Concept of the Goetheanum

GA 289

16 October 1920, Dornach

Translated by Steiner Online Library

3. The Double Dome Room and Its Interior Design

It may be clear from the two observations already made here about the building idea of Dornach how this building idea has arisen out of the same life from which that is to arise which is meant here as spiritual science. But this building idea did not arise in such a way that, in the building, what lives in thought form, in idea form, in spiritual science, is to be found again, only in outwardly symbolic pictorial form. Rather, the building was to arise out of the feelings and perceptions that can be harbored by someone who feels inspired by this spiritual science. To some extent the intention was there: on the one hand, the spiritual-scientific impulse wants to express itself in the form of ideas. But that is not enough, that does not reveal its life in a complete way, and another branch must sprout from the common root. That is precisely the artistic branch, that is what manifests itself out of feeling and perception in the building idea of Dornach.

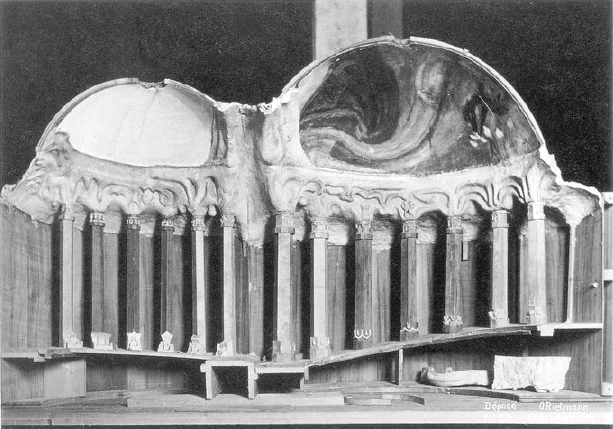

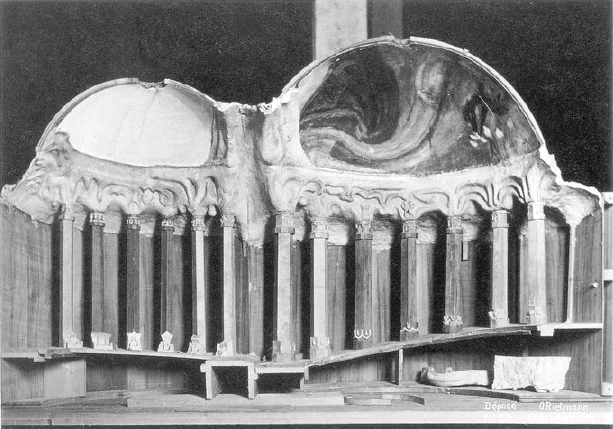

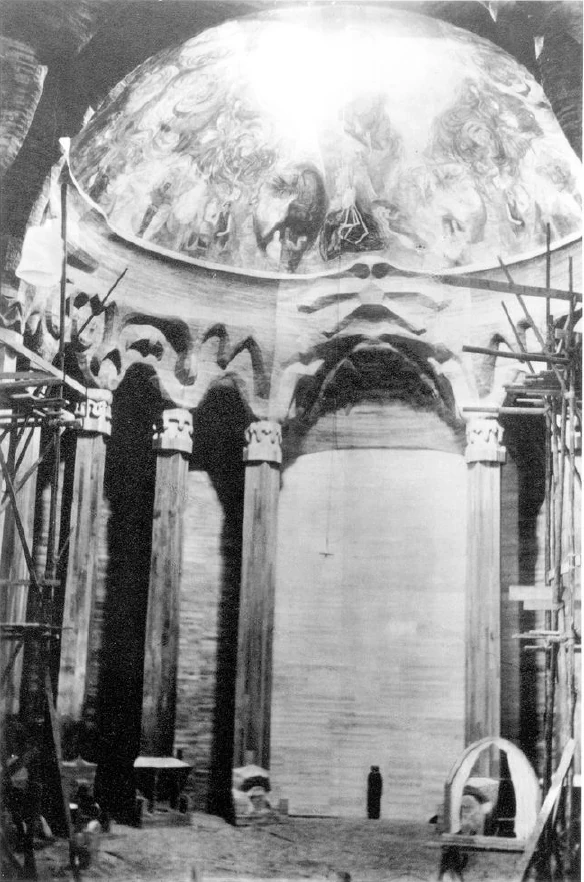

Those approaching this building from the outside will at first perceive a kind of duality: a larger dome structure as an auditorium; a smaller dome structure, which to a certain extent cuts through the larger one , as a space for performances, also conceived as the space towards which everything in the auditorium tends, and from which, in turn, everything that the auditorium is inclined to absorb should radiate. Our future development will depend on whether humanity is able to commit itself to a truly essential development in all its soul-forming aspects, to commit itself to development in such a way that one says to oneself: What one has inherited or acquired through ordinary life does not yet lead to what gives the human being a truly dignified existence. From a certain point onwards, the development of the inner life must be taken up in order to lead beyond what the outer consciousness alone can bring. But there must be something to meet what one is approaching and which one expects, as it were, from unknown depths of the spirit. And it is the feeling of this interaction between the receiving human being and the creating human being within himself that was then able to be lived out in the building idea of Dornach.

From the outset, wherever domed rooms of different sizes adjoin or even intersect, one cannot help but feel that a close interaction is taking place between the person to whom the one part is dedicated and the person to whom the other part is dedicated. To a certain extent, the aim was to evoke the sensation of a rhythm that exists between the larger and the smaller component. This lively sensation, or perhaps it would be better to say this invigoration of sensation through the forms of the building, could hardly be evoked by two rooms adjacent to one another in a different way. But now that is adapted to what interior design is and from which I would like to start initially.

You know that in the case of all the buildings that are actually designed to enclose something, we are dealing with a completely different architecture. Perhaps we can reach an understanding if we point to older building forms that draw their style, their architectural concept, from completely different premises. The Greek “temple is conceived as the dwelling of the god, and a Greek temple in which there is no statue of the god, of Zeus, Apollo or Athena, would not be a complete work of art. But how did this style actually come about? It arose, so to speak, from the idea of God acting from a specific point in the universe. It is intended to envelop the activity of this god; it is therefore conceived in its entirety as a covering, as an enclosure.

If we go a little further, skipping other architectural styles, to the architecture of the later Middle Ages, to the Gothic cathedral, we have to say that anyone entering a Gothic cathedral cannot feel that this building is complete if it is empty. A Gothic building that is not conceived as a temple but as a cathedral, that is, as a gathering and confluence of the faithful, is only complete when the faithful are assembled in it, when they are inside, just as a Greek temple is only complete when the statue of the god is inside. Accordingly, the entire Gothic architectural style is conceived in this way.

And now, penetrating into our times, one is led to say: the internalization of the human being is what must be the essential impulse of the present and the near future. Man himself, with his inwardly divine-spiritual essence, is at the center of all striving, but he kills this inner impulse of his modern striving if he does not find his way into the development in a living way. And it is from this feeling of the modern human being that the building idea here has arisen. The mere all-round principle of symmetry of Greek architecture, the enclosure, had to be dissolved, and the abstract idea of the upward striving of the crowd gathering in the cathedral also had to be dissolved. Closure had to be found, so to speak, in the upward infinity of the spherical form, development in the complete feeling for that which animates the individual form.

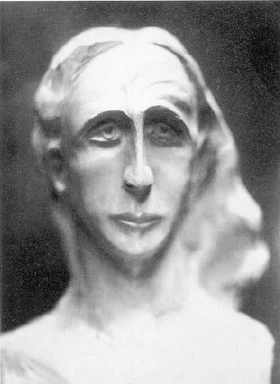

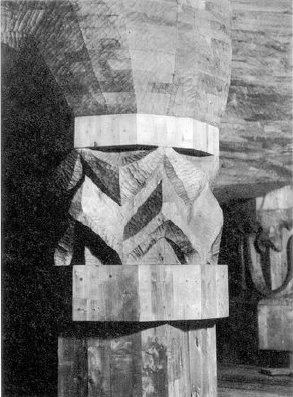

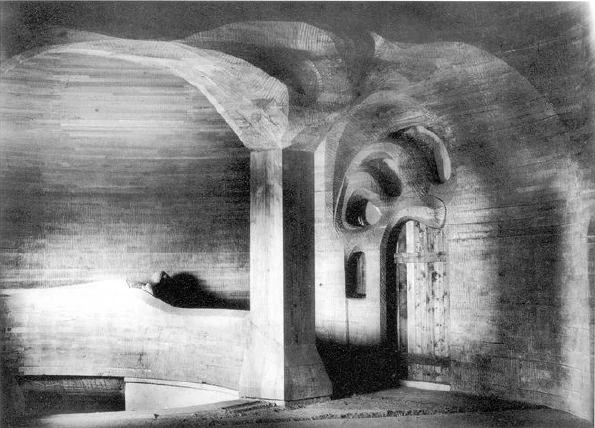

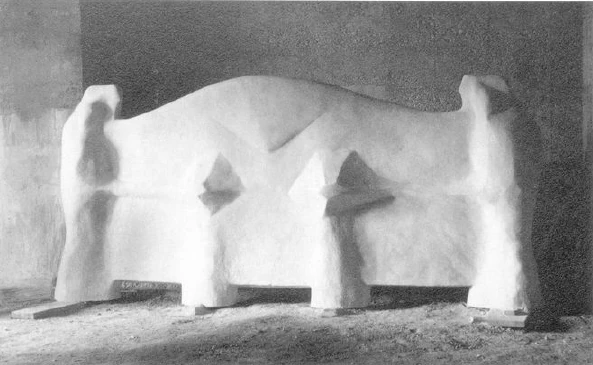

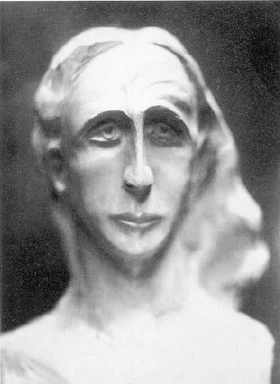

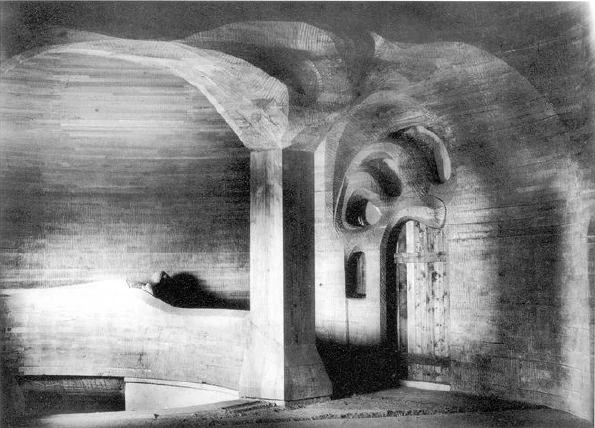

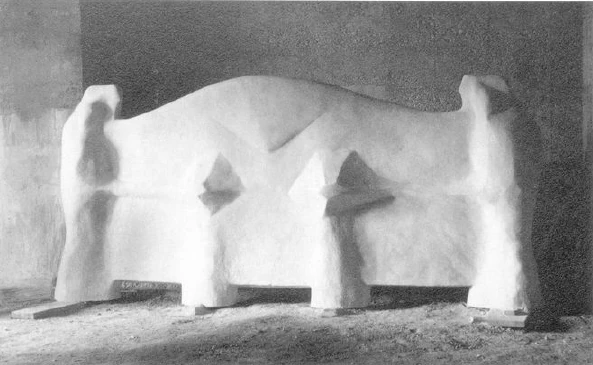

It is perhaps partly due to external motives that part of this building is a wooden structure; it could just as easily be a concrete structure, but not, for example, a marble building. Now that it is a wooden building, I only need to speak about the peculiarity as a wooden building, which essentially presents the interior design. When working with wood as a material for architecture, for sculpture, one notices that this work in wood is something quite different from working in marble, for example, or in any material that reveals itself on the surface like marble or stone. This will be particularly apparent when the central group in the right light is seen standing in this small domed room on the east side (Fig. 92). It has become a sculptural wooden group in keeping with the overall interior design. So it was worked in wood. Of course, it was he who made a model first, since no single person can work on a nine-and-a-half-meter-high wooden group. I would not have been surprised if the people who saw this model, which was made in plasticine, had actually found it hideous, especially the central figure, the representative of humanity himself. For it goes without saying that the final design in wood must already have been present in the plasticine version.

But now, when working on stone – or on a surface that can resemble stone – one is obliged to carve out the form from the raised parts, from what bulges out of the plane, what confronts one from the plane; one is therefore obliged, so to speak, to place it on the plane, on the surface. When working with wood, you have to avoid working on the wood itself and instead work out of the wood. One must work not towards the convex but towards the concave. With stone and everything that resembles stone, it is that which emerges from the surface, the convex, that is effective. With everything that is made of wood, it is that which withdraws from the surface, that which is thus, as it were, cut out, hollowed out of the wood.

Therefore, it is necessary – and I ask you to visualize the whole type, let us say, of the Roman Caesar heads, which can be seen everywhere in casts in museums, in relation to what I am about to say – therefore, when you sculpt the human form out of a stone-like material, you have to work the whole thing out from the face, from the head, and the rest of the human form that is not the head is actually, artistically speaking, just an appendix to the head. One must not, so to speak, sin against the natural forms of the human head, and one must shape the entire organism of the limbs and trunk out of what is laid down in the head. All this is required, for example, of marble, all this is required of stone.

If one works in wood, then one has the necessity to work in the opposite sense. You have to work from the whole human figure, from the movement of the limbs, from the feeling of the torso. You can dare to shape an upward arm movement, a downward arm movement in such a way that it continues in an asymmetrical forehead, as was attempted with this group. This was only possible because it is a wood group, because when you work in wood, you bring out the hollows in the material and do not place what is raised on the surface. Only by being completely immersed in the material, with all one's feelings, especially in the human form, can such a treatment of the material emerge.

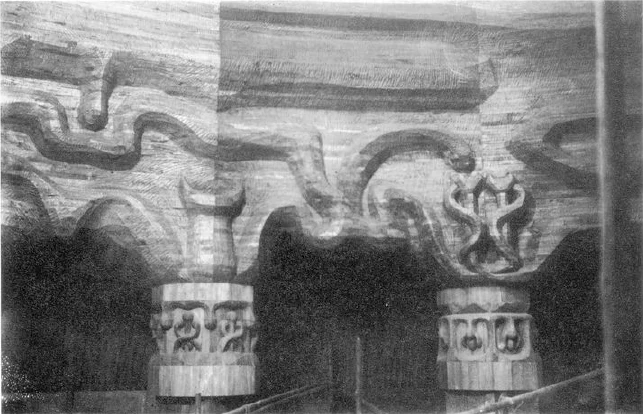

And what is most vividly apparent when the human form is sculpted is apparent in the overall treatment of the wood here in this interior design. In stone, the progression of the columns from the simplest capital and pedestal forms to the more complicated middle forms, and then back to the simple forms again, would represent the dissolution of the symmetry on all sides into a developmental metamorphic progression. In stone, all of this would be nonsense; because stone demands to be more comprehensive, stone demands symmetry on all sides. Only wood allows for the development that was attempted here. As I said, it could also have been done in concrete, which, due to its nature, overcomes stone; only the form would look somewhat different. But wood allows for the introduction of development into the shape of the capital.

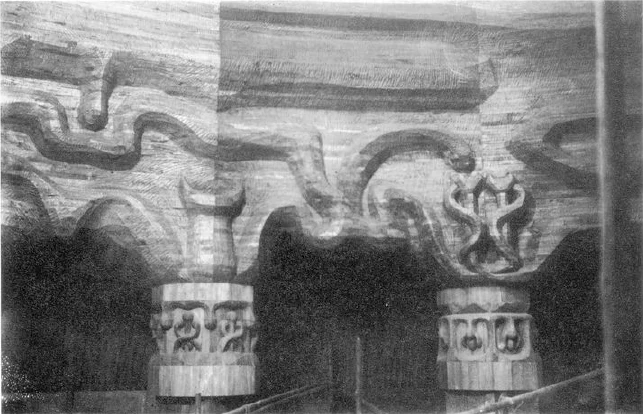

And here I would like to say that the underlying idea was to implement Goethe's concept of metamorphosis in the purely artistic. One must, however, completely immerse oneself in the creative powers of nature and create forms out of the creative powers of nature if one dares to attempt to progress from the simplest capital forms, which you can find here at the two columns at the entrance, to ever more complicated forms. But that came about all by itself, that came about for the senses, that was not contrived. Those personalities who in earlier times were often led here in this building were told: this column means this, that column means that; they were spoken of Mercury, Mars columns and the like, and in these things, which actually only serve an abstract understanding, one has seen the main thing. The main thing is not in that. The main thing is how the second capital motif - but now for artistic perception - emerges from the first with the same necessity as the higher-lying leaf or blossom emerges from the lower-lying leaf according to the principle of natural growth, or the petal from the leaf. When forming such a concept, one looks at nature theoretically. Here it is a matter of having nothing to do with theory, but of experiencing the development as one form arises from the other. I may say: everything that you see here in the way of capitals and architraves is felt to be absolutely pure, and anyone who speculates about it, who makes symbolic interpretations about it, misunderstands the whole thing.

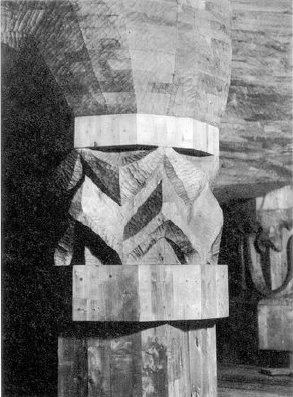

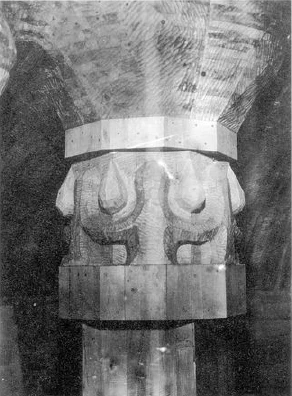

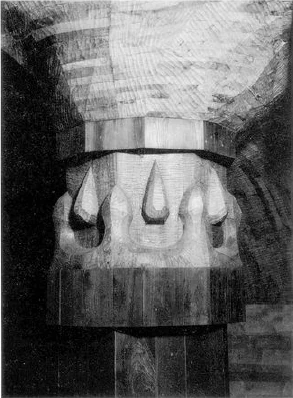

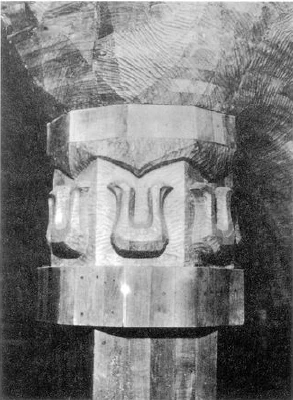

But it is strange how, when you are working, this interweaving with the creative powers of nature brings surprises. When I was working on the model for this building (Fig. 22), I merely had the feeling that one capital would emerge from the other, that the next architrave motif would always emerge from the previous metamorphosis, and so on with the base motifs and so on. It soon became clear to me that this developmental impulse does not lead to a progression from the simpler to the more complicated, but that the most complicated is achieved right in the middle, as you can see here on the central columns, and that, in turn, when you have taken complexity to its ultimate height, to its culmination, you are compelled to move on to something simpler. Therefore, you do not see here, for example, an abstract development that starts with the simplest and progresses to the most complicated, so that the last would be the most complicated, but you see the greatest complication of the motifs in the middle.

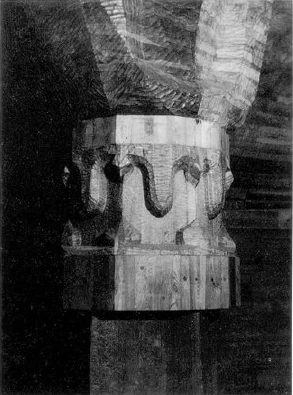

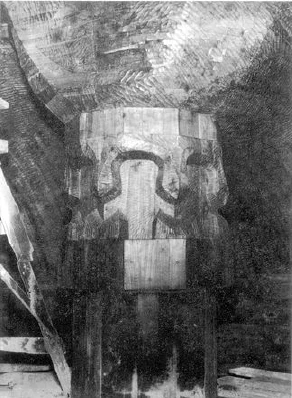

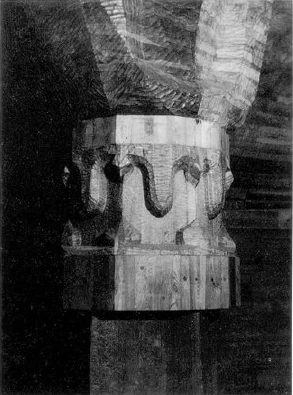

And then I may also reveal to you here that it was certainly not intended from the outset to be a staff of Mercury entwined by snakes (Figs. 41, 42). No, that arose out of the artistic experience as something that cannot be otherwise if one ascends to the complicated in development and then has to turn around in order to descend again into the simpler. Likewise, I was surprised, for example, when – having arrived at the seventh column – I found that the sublimities of the first column, if you think of it as being turned inside out like a glove – not geometrically, but artistically turned inside out — fit exactly into the cavities of the last column; how, in turn, the same is the case with the second and sixth columns, as it is with the third and fifth columns, and the fourth column is in the middle.

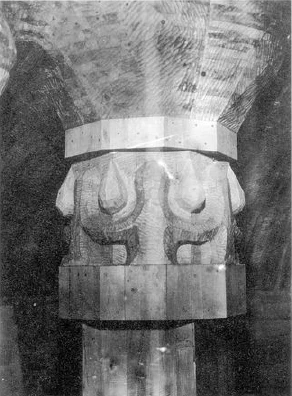

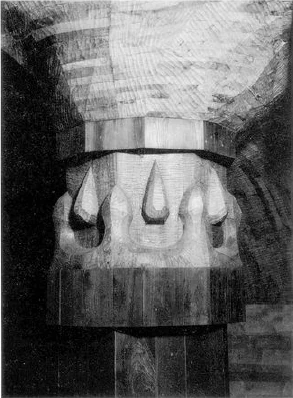

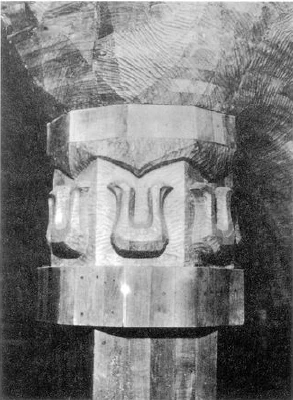

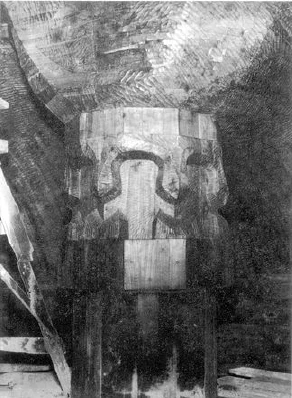

It was not a case of pursuing some abstract, mystical principle of seven from the outset; rather, just as the tone scale is a seven-part entity, here the columns had to be formed in such a way that, so to speak, an octave of feeling in the form is fulfilled in a seven-part structure. For the eighth would be the octave; there it has to merge into the other kind of feeling, which one then finds in the small domed room, which contains something that accommodates development as an absorption. Therefore, the capital motifs of the small dome (Figs. 58-63) are not presented in their developed form as they are here, but are rather presented as a single entity, so to speak, opening its arms to what hastens towards it as a development.

But all this is not said beforehand, because beforehand one is dealing with something else, with life in form, with life in the plane itself. This is said afterwards, to give some indication of what has been created. Nothing here has grown out of any newer theoretical world view, not even out of the world of ideas of spiritual science itself. And I believe that it can be achieved, at least to a certain extent, that those who enter this building have the feeling: here, for the time being, one can forget everything one has absorbed in one's head in the way of spiritual-scientific ideas and thoughts. There is no need to talk about it, but one can feel it, feel it from the forms and from the treatment of the forms.

So that one can feel something like this: When you enter a Greek temple, you feel the encompassing nature of this Greek temple. The stone form reigns in wisdom. From the macrocosm comes the wisdom that builds this macrocosm, pushes through the wall, as it were, and works in the stone's sublimity, in the convexities, and there encompasses the externally resting God, who is only active in the spirit for the world. One could feel in a similar way that which is striven for in a Gothic building. It is the community with its group soul, which, by being gathered in the cathedral, actually has around it that which it itself has built, bricked, chiseled, carpentered, and so on. When one enters a Gothic cathedral, one always has the feeling that, in contrast to the Greek temple, which arose from a purely aristocratic way of thinking, the Gothic cathedral is the product of a class-conscious thinking, of the structure of medieval life, which expresses itself through the search for humanity, which also expresses itself in its forms in this search for humanity.

Those people who cannot bring themselves to look at it impartially speak of the Temple of Dornach. What has been built here is the opposite of any temple. There is nothing temple-like here, nothing that can be related to a church or a cathedral. And anyone who speaks of the temple of Dornach is only expressing how they have remained with Greek architecture in their whole feeling, not even having progressed to the Gothic. Here, however, what had to be tackled was that which creates forms that are basically only the continuation of what is spoken here, what is played here, what is declaimed here, what is artistically presented here. And just as the speaker stands here at the lectern, just as the organ sounds from above, just as the recitative tones vibrate through the room, so that which originates from the word, from the sound, from the thought must continue to speak through the framing, through the enclosure, which is not an enclosure but only continues the spoken, the sounded word. In the Greek temple we are dealing with an enclosure; here we are dealing with a self-expression. Therefore, above all, the whole form must be such that it lovingly embraces what is happening here, but that it does not close it off, but that this building stands as a symbol that what is being worked on here in Dornach should reach out to all of humanity.

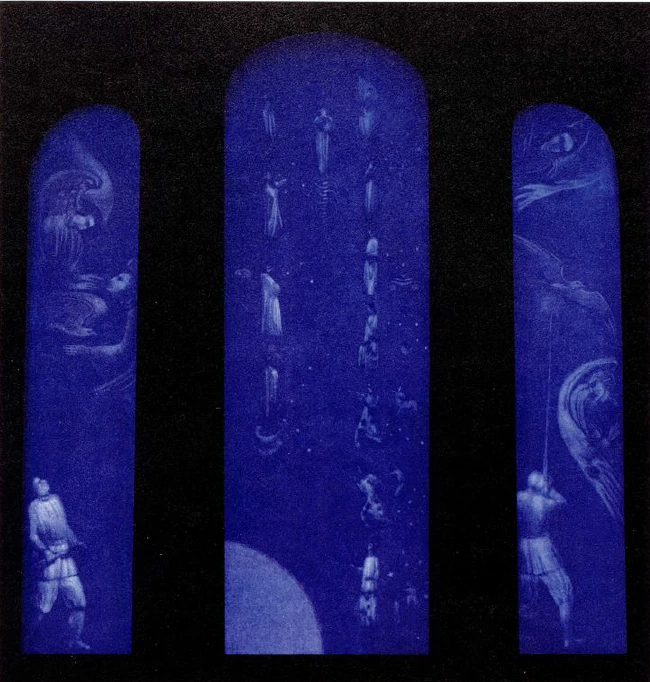

If you study the columns here, together with the back wall, which signifies enclosure, you will see that The whole can now be felt in such a way that nowhere does one have the feeling of being enclosed and speaking only to the wall; rather, one has the feeling that one is speaking and the forms of the wall, these capitals, these architraves, these column forms absorb the vibrations of the word and actually want to carry them out into the world. They do not want to close off, but want to be artistically transparent. And just as the wood here is cut in such forms that make the wood artistically permeable, so it is suggested in these windows, I would say in a more natural material way, how what is here inside should be connected with the outside. These windows are not works of art in themselves; these windows, whose technique is essentially a glass etching technique, are only works of art when sunlight shines through them, when a connection is created between what has been scratched out of the glass and the sunlight shining through. That doesn't close, that lets the sun in, that is the living mediator with the whole, with the light that floods the cosmos, and is only something if you look at it in connection with this light.

If you approach it in such an artistic way, then you can also dare to develop the motifs that are in these windows.

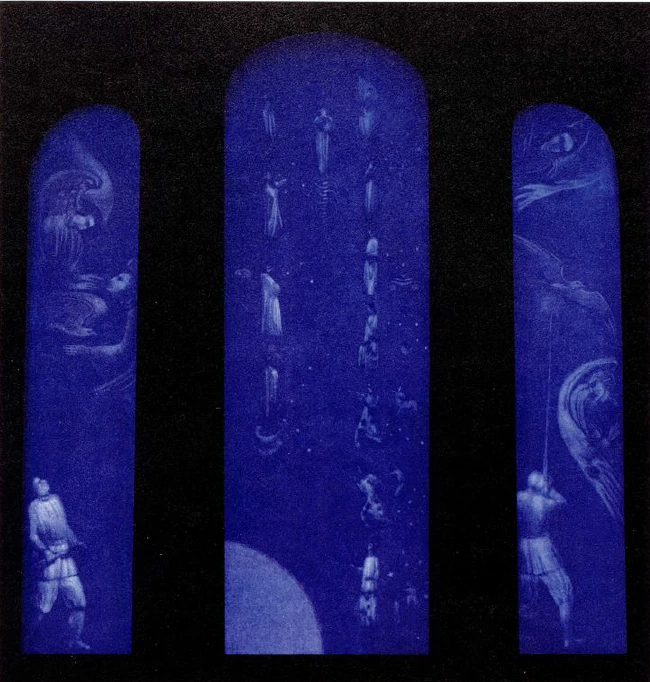

I cannot go into details, of course, but I would refer you to that blue window there (Fig. 111), where you can see the human form in both casement windows, the human form in two situations. In one case, all the qualities that live in the hunter when he aims at the animal he wants to shoot live in the person. In what has been scratched out of the glass, you will find the entire inner life of the person depicted, you will find everything that lives in him poured into the figurative. When you come to a certain stage of inner experience, you cannot help but give shape to what lives inside as passion. And if you then think of the metamorphosis as having progressed, the whole picture shows the following in the right-hand window: the person has progressed from intending to shoot the bird down to actually doing it: he has taken aim and is shooting. What happened earlier is transformed into the other part, which is then scraped out of the glass and together with the sunlight gives the work of art. In this way, each individual window could be treated. But the point here is not to come up with more interpretations, but to surrender to what is on the glass, to feel it. Precisely when one strives for the art of interpretation, one overlooks the actual artistic intention therein.

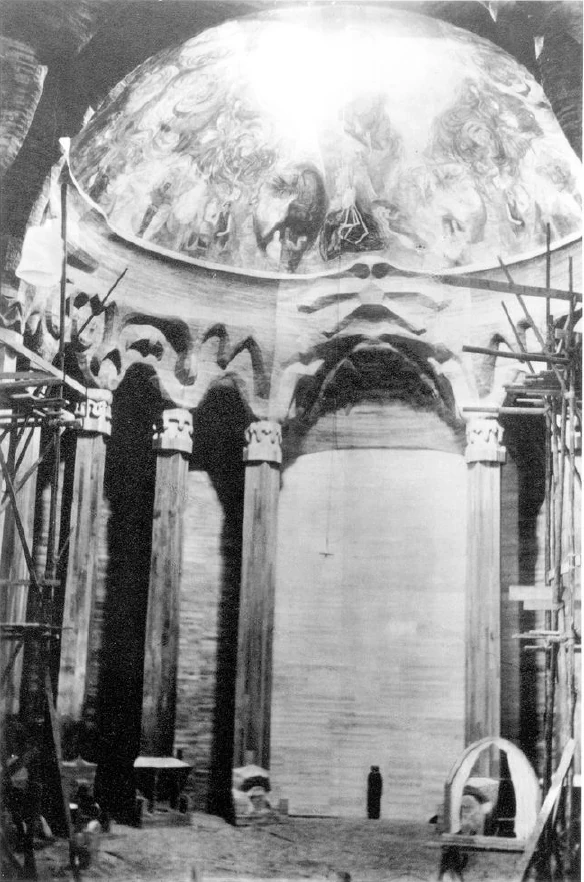

And when you look at this dome painting (Fig. 57) and see how everything that is painted in the small dome is brought out of the color, then you will also have the aspiration there to feel your way out of the closed space into the cosmos. It is painted in such a way that the painting on the surface is suspended, as if you are entering through a portal into a living thing. If you have a vivid sense of color, you can draw that out of the color. Of course, there are people who would prefer to see naturalistic figures up there; that would spare them the discomfort of first having to feel things. Because what you can feel in a beautifully—what we call “beautifully”—painted naturalistic human figure is something you have felt since childhood, and it is comfortable to see it again. But when you come here, you don't have the opportunity to rediscover what you have felt since childhood and say that it resembles this or that, but rather, here you have to, so to speak, go through all the that you have gone through in your entire life, in order to grasp in a lively way what emerges from the colors and the forms – which are, after all, the work of the color; they want to be nothing else – and to have the feeling: it does not shut you out, it carries what you feel here out into the whole world, it connects you with the world. Nothing about this building is conceived as anything other than an organic formation.

It was certainly a daring move to transfer mechanical forms of construction into the organic. If you want to develop something organic, everything has to be so that it could not be any different at the place where it occurs. Take something as insignificant as a human earlobe, which is certainly something very insignificant in the human organism. But according to the nature of the human organism, this earlobe, with its very specific shape, must form at this location here, and of course a similar organ could not develop, say, at the tip of the little finger or elsewhere. Each has its shape in its own place.

This has been developed here as a building idea. Everything you see formed here (Fig. 27) has been thought out from the whole, has been thought and felt into the place where it stands. The column is dissolved in such a way that one can see the supporting function of the dissolved column in its form. If you see any motif outside at the entrance, you will see from its forms: This is towards the entrance. If you step a few steps further inside, what the column has to bear is no longer there in the same way. But if you go from the outside world into what such a column structure has to bear, the load-bearing and pushing of the whole structure against each column structure should be felt and, in turn, the relief against the outside world. What we are seeking here is an inner dynamism that strives towards life. And we live in a time when such a metamorphosis must be striven for in all fields of human endeavor, as was rightly felt in the past.

I am reminded of Schlegel, who, looking at the past forms that the “Renaissance men” repeatedly wanted to bring back, coined the beautiful phrase: “Architecture is frozen music.” It is a beautiful phrase for everything that has gone before in architecture, and an extraordinarily apt one. One has the feeling that music lives in these building thoughts. How could one see more beautifully than in the building forms of the Greek temple! How could one feel Bach, prophetically foresaw, differently than in the forms of the Gothic cathedral! The fugue already lives in the pointed arch. There it was frozen, and Friedrich Schlegel was right to call architecture, which he knew, frozen music.

But today we live in a momentous moment of human development. We live in the moment when all creativity must take on a different form. And so we must also thaw and melt the frozen form of architecture. But it would dissolve into the indefinite if it were not imbued with soul in the melting process. And so we must have, alongside the frozen music, a thawing music that looks at us and demands: Give me soul! That, you see, is something of the building idea at Dornach, which spoke out of the development of humanity: thaw me, I am the frozen music! But I would melt into nothingness if, in thawing, the soul, the soul that is intensely moved within, did not lead into all forms. Not mere symmetry-proportionality should live in the forms, not merely that which one capital places in symmetry and proportionality next to the other, but living, intense movement, which allows one capital to grow out of the other like one petal of a flower out of another, metamorphosically transforming the form.

I know all the arguments that can be used against this transfer of the idea of construction from the dynamic-mathematical to the organic-living, and I understand every one of the artists who cling to the old in this direction; I feel for them. But a start had to be made sometime with what time, from its depths, demands of us humans in the present and for the near future. And so only those who experience it as a need of their own soul, which has struggled to meet the demands of the present and the near future, will feel this structure. Of course, there is still a lot that is imperfect, and if it were to be performed a second time, this building would look quite different. But nevertheless, you can see from the attempt, at least, how the attempt has been made down to the smallest detail to transfer the dynamical-mathematical into the organic.

Take a look at the radiators (Fig. 26). See how they are created from an organic, living elementary form, as if certain forces, which mysteriously work in the earth's interior, wanted to continue to work over the earth's surface. A few days ago, you were given a hint here as to how electricity continues to work in a mysterious way in the earth, when what is only transmitted through a wire is closed to the power circuit through the earth line, as it were, the whole earth replaces in its powers what would have to be there in a second wire line. Oh, there is much that is mysterious in the earth. But what is mysterious in the earth can be unraveled, not intellectually but intuitively. When it is shaped into forms, which should not be slavish imitations of animal or plant forms, but which are quite independent forms, then one perceives them as being alive. You can then form a wide, low stove screen and make the shape differently than if you were making a narrow, tall stove screen. You have the metamorphosing principle within you; it passes into the creative hand.

Of course, these are all things that people of the present day may still find repulsive. Let them do it. Those who cling to the old have always found what has emerged as something new repulsive. But such an experiment must be ventured some time. Here it was not even ventured out of the abstract, but it was undertaken because a second, an artistic branch wanted to emerge from the same roots from which spiritual science itself emerged. And I would like to emphasize once again: you will not find a single symbol in this room. If anything here appears to you as a symbol, it could at most be the five-petalled flower leaf at the back in the small domed room (Figs. 55 above, 57), which could appear to you as something that is meant to be symbolic when the curtain is raised later. Just as the five petals do not symbolize a pentagram, nothing here is meant to be symbolic. But everything has been so carefully thought out that every detail, every artistic line, is derived from the form of the whole.

If I have been permitted to characterize the building idea of Dornach in this way, it must be understood that I must at the same time add that what I have said is only the beginning of an attempt. And you can be sure of this: those who are working on this building, those from whom this building idea has arisen, do not think of it in an immodest way. They think about it in such a way that they would certainly retain the impulse, principle and style, the essentials, but create something completely different after they have learned what can be learned in the process of creating this building. A lot could be learned here. Because you truly do not learn more thoroughly than when you are forced to let what lives in your soul flow into concrete action. It is relatively easy to contrive abstract ideals with great perfection. But if one is compelled, already at the very first steps that an idea, an impulse inwardly takes in the soul, to shape this idea, this impulse in such a way that it can weave in the outer material, so that the work in which it embodies itself, does not become allegorical, then it requires something quite different in inner experience, then it requires a growing together with the world thought, with the world impulses, with that which lives in the world.

Therefore, the Greeks, who were able not only to think about the world but also to feel it, took the word “cosmos”, with which they designated the universe, not from theory but from feeling. In the word “cosmos” lies the sense of beauty that is aroused in us when we look at the outer universe. But today, anyone who carries the thought of building in reality in their soul must be able to experience and grasp human development itself in a cosmic artistic way. We place ourselves in the sight of the portal of a Greek temple. We enter the temple. We experience the forms that surround us as a fence around the image of the god. We feel something like wisdom cast in form, that wisdom that flows through the whole world and that once had to emerge artistically in external forms, that had to be felt and that was felt in the highest way when the temple was created as the dwelling place of the Greek god.

We must have a different material from the stone that allows us to shape world wisdom in its sublimity; we must have a different material when we work from the innermost being of the modern human being; for a different force must radiate out into the universe than wisdom is. We receive wisdom; it radiates towards us from what we place on the surface in terms of sublimity, of convexities. When we stand before the soft wood, we hollow into it that which lives in us, and we give something of ourselves to the cosmos. But as human beings, if we do not want to sin against the whole spirit of the world, we must carry nothing into it but what is carried into the universe on the stream of love.

And anyone who can feel artistically, feels when he shapes the marble out of the flat surface, how wisdom comes over him in his consciousness when he carries out the building idea of the marble. The person who executes such a building idea as the one here feels that he must create what can be created by carving into the soft wood, what can live in the concavity, in true devotion to the greatness of the universe. One may only carve into it if one carves into it with love for the universe. No one should actually be able to form a surface with a relief without being overwhelmed by the wisdom of the universe. No one should dare to commit the sin of imprinting their own human essence on the material, of hollowing out the material, who does not do it with love for the universe. These, however, are the two poles of all human development: idea or wisdom and love. When we read Goethe's sayings in prose, it sounds to us like a fundamental solution to the riddle of the world when Goethe says: The highest that man can feel is the harmony of idea and love.

We are aware that this harmony has been achieved here, for the time being only, I would almost say haltingly, in what we have now been able to do. But according to the intentions from which its idea has flowed, this structure does not want to be anything other than a germ. But a germ must not be judged only by what it initially presents itself as; a germ must be judged by what can grow out of it. These courses have been organized to help get this germ growing. And we have called you here because you are part of this building idea from Dornach. For whatever I might relate to you about the building idea of Dornach, it would all have to be unfinished, because this building idea can only be completed by those who have felt it going out into the world and - each in his own place - accomplishing that to which this building idea, with all that can be cultivated in the building, is to be the germ. I can only speak to you of something unfinished.

To complete what is intended here, that cannot be done in Dornach, not by those who would work here, however fully; that can only be done effectively by you, by going out into the world and completing what can be hinted at here but must remain unfinished. You are not called upon to admire or evaluate the building, but to complete it, to be the further material in which the world spirit itself works, in which it is freely grasped by you so that in today's social distress, in today's decisive moment in world history, something may be done for the further development of humanity that leads not to barbarism but to a new, luminous ascent of human development. We would like the walls, columns, windows and domed spaces to speak to you: become the fulfillers of the architectural vision of Dornach! For it is in this sense that we have truly counted on you.

3. Der Doppelkuppelraum Und Seine Innenarchitektur

Es wird vielleicht aus den beiden Betrachtungen, die hier bereits gegeben worden sind über den Baugedanken von Dornach, hervorgehen, wie dieser Baugedanke entsprungen ist aus demselben Leben, aus dem das hervorgehen soll, was hier als Geisteswissenschaft gemeint ist. Aber nicht so ist dieser Baugedanke entsprungen, dass gewissermaßen in dem Bau das noch einmal gefunden werden soll, nur in äußerlich symbolisch bildlicher Form, was in Gedankenform, in Ideenform in der Geisteswissenschaft lebt, sondern der Bau sollte hervorgehen aus den Gefühlen und Empfindungen, die derjenige hegen kann, welcher zu dieser Geisteswissenschaft sich angeregt fühlt. Gewissermaßen war vorhanden die Intention: Auf der einen Seite will sich ausleben der geisteswissenschaftliche Impuls in Ideenform. Aber das erschöpft ihn nicht, das offenbart sein Leben nicht auf eine vollständige Art, und es muss ein anderer Ast aus der gemeinsamen Wurzel heraussprossen. Das ist eben der künstlerische Ast, das ist das, was aus Gefühl und Empfinden heraus sich im Baugedanken von Dornach manifestiert.

Wer von außen sich diesem Bau nähert, wird ihn zunächst empfinden müssen als eine Art von Zweiheit: ein größerer Kuppelbau als Zuschauerraum; ein kleinerer Kuppelbau, der gewissermaßen den größeren durchschneidet, als Raum für Aufführungen, auch gedacht als der Raum, zu dem alles hintendiert, was im Zuschauerraum ist, und von dem gewissermaßen all das wiederum ausstrahlen soll, was der Zuschauerraum geneigt ist aufzunehmen. Unsere künftige Entwicklung wird ja davon abhängen, ob die Menschheit in der Lage ist, sich selber in ihrer ganzen Seelenartung zu einer wirklich wesenhaften Entwicklung zu bekennen, so zu der Entwicklung sich zu bekennen, dass man sich sagt: Was man ererbt oder durch das gewöhnliche Leben erzogen hat, das führt noch nicht zu dem, was dem Menschen ein wahrhaft menschenwürdiges Dasein gibt. Von einem bestimmten Punkt an muss die Entwicklung des Innern aufgenommen werden, um über dasjenige hinwegzuführen, was das äußere Bewusstsein allein bringen kann. Es muss aber etwas dem entgegenkommen, dem man sich da nähert und das man gewissermaßen aus unbekannten Geistestiefen heraus erwartet. Und das Empfinden dieses Zusammenwirkens des aufnehmenden Menschen und des in sich schaffenden Menschen, das ist es, was sich dann ausleben konnte in dem Baugedanken von Dornach.

Man wird ja von vornherein da, wo verschieden große Kuppelräume aneinandergrenzen und sich sogar durchschneiden, das Gefühl haben, dass eine innige Wechselwirkung stattfindet zwischen demjenigen, dem der eine, und demjenigen, dem der andere Bauteil gewidmet ist. Gewissermaßen wurde gesucht, die Empfindung hervorzurufen von einem Rhythmus, der zwischen dem größeren und dem kleineren Bauteil besteht. Durch zwei in anderer Weise aneinandergrenzende Räume würde kaum diese lebendige Empfindung, oder vielleicht besser gesagt, diese Belebung der Empfindung durch die Formen des Baues hervorgerufen werden können. Dem aber ist nun dasjenige angepasst, was Innenarchitektur ist und von dem ich zunächst ausgehen möchte.

Sie wissen, dass bei all den Bauten, welche eigentlich so gedacht sind, dass sie wirklich etwas umschließen, man es mit einer ganz anderen Architektur zu tun hat. Man wird vielleicht sich verständigen können, wenn man etwa hinweist auf ältere Bauformen, die ihren Stil, eben ihren Baugedanken, aus ganz anderen Voraussetzungen herausziehen. Der griechische "Tempel ist gedacht als das Wohnhaus des Gottes, und ein griechischer Tempel, in dem nicht die Götterstatue wäre, der Zeus, der Apollon, die Athena, wäre eben nicht ein vollständiges Kunstwerk. Aber wie ist dieser Stil nun eigentlich zustande gekommen? Er ist gewissermaßen entsprungen aus dem Gedanken des im Weltenall von einem bestimmten Punkte aus wirksamen Gottes. Er hat zu umhüllen die Wirksamkeit dieses Gottes; er ist daher in seiner ganzen Form als Umhüllung, als Umschließung gedacht.

Geht man ein wenig weiter, andere Baustile überspringend, zu dem Bau des späteren Mittelalters, zu dem gotischen Dom, so wird man sagen müssen, dass derjenige, der einen gotischen Dom betritt, nicht fühlen kann, dass dieser Bau vollendet ist, wenn er leer ist. Der gotische Bau, der nicht als Tempel, der als Dom gedacht ist, das heißt als Zusammenschluss und Zusammenfluss der gläubigen Menschenmenge, der gotische Dom ist nur vollständig, wenn in ihm die gläubige Menge versammelt ist, wenn sie drinnen ist, so wie der griechische Tempel nur vollendet ist, wenn die Statue des Gottes drinnen ist. Darnach ist wiederum dieser ganze Baustil der Gotik gedacht.

Indem man nun herüberdringt in unsere Zeiten, kommt man dazu, sich zu sagen: Die Verinnerlichung des Menschen, das ist dasjenige, was der wesentliche Impuls der Gegenwart und der nächsten Zukunft sein muss. Der Mensch selbst mit seiner innerlich göttlich-geistigen Wesenheit tritt in den Mittelpunkt alles Strebens, aber er ertötet diesen inneren Impuls seines neuzeitlichen Strebens, wenn er nicht in lebendiger Art sich in die Entwicklung hineinfindet. Und diesem Empfinden des modernen Menschenwesens ist der Baugedanke hier entsprungen. Aufgelöst musste werden das bloße allseitige Symmetrieprinzip des Griechentums, die Umschließung, und aufgelöst musste auch werden das abstrakte Vorstellen des Aufstrebens der sich im Dome zusammenfindenden Menge. Abschluss musste gewissermaßen gefunden werden in der Unendlichkeitsform des Kugeligen nach oben, Entwicklung in dem ganzen Erfühlen desjenigen, was die einzelne Form beseelt.

Es ist im Grunde genommen vielleicht teilweise aus äußerlichen Motiven entsprungen, dass ein Teil dieses Baues ein Holzbau ist; er könnte ebenso gut ein Betonbau sein, aber nicht zum Beispiel ein Marmorbau. Nun, da er ein Holzbau ist, habe ich ja nur nötig, ü Eigentümlichkeit als Holzbau zu sprechen, der ja im Wesentlichen die Innenarchitektur darbietet. Man merkt bei dem Arbeiten mit Holz als Material des Architektonischen, des Plastischen, dass diese Arbeit in Holz etwas ganz anderes ist als etwa die Arbeit in Marmor oder überhaupt in einem Material, das sich seiner Oberfläche nach so offenbart wie der Marmor oder der Stein. Man wird das insbesondere gewahr werden, wenn man einmal jene Mittelpunktsgruppe im rechten Lichte sehen wird, die da in diesem einen kleinen Kuppelraum an der Ostseite stehen wird (Abb. 92). Sie ist entsprechend der ganzen Innenarchitektur eine plastische Holzgruppe geworden. Sie wurde also in Holz gearbeitet. Selbstverständlich war er seine es, da ja nicht eine einzelne Persönlichkeit an einer neuneinhalb Meter hohen Holzgruppe arbeiten kann, dass zuerst ein Modell gemacht wurde. Ich hätte mich nicht gewundert, wenn die Menschen, die dieses Modell, das in Plastilin ausgeführt war, eigentlich scheußlich gefunden hätten, insbesondere scheußlich gefunden hätten die Mittelfigur, den Menschheitsrepräsentanten selber. Denn selbstverständlich musste in der Plastilinbearbeitung die zuletzt im Holze stattfindende Ausgestaltung schon vorschweben.

Nun hat man aber, indem man auf Stein - oder auf ein solches Aussehen, wie es der Stein darbieten kann — hinarbeitet, die Notwendigkeit, herauszuarbeiten die Form aus den Erhabenheiten, aus dem, was sich herauswölbt aus der Ebene, was einem entgegentritt aus der Ebene; man hat also die Notwendigkeit, gewissermaßen auf die Ebene, auf die Fläche aufzusetzen. Wenn man in Holz arbeitet, hat man die Notwendigkeit, nicht auf das Holz aufzusetzen, sondern aus dem Holze herauszuholen. Man hat hinzuarbeiten nicht auf das Konvexe, sondern auf das Konkave. Beim Stein und bei alledem, was steinähnlich ist, wirkt dasjenige, was heraustritt aus der Fläche, das Konvexe. Bei alledem, was aus Holz ist, wirkt dasjenige, was zurücktritt aus der Fläche, was also gewissermaßen herausgeschnitten, herausgehöhlt wird aus dem Holze.

Daher ist es notwendig — und ich bitte Sie, einmal sich zu vergegenwärtigen die ganze Art, sagen wir, der römischen Cäsarenköpfe, die ja überall in Abgüssen in Museen zu sehen sind, auf das hin, was ich jetzt sagen werde -, daher hat man, wenn man plastisch die Menschengestalt herausarbeitet aus einem steinähnlichen Material, die Notwendigkeit, das Ganze aus dem Antlitz, aus dem Kopfe herauszuarbeiten und die übrige Menschengestalt, die nicht Kopf ist, ist eigentlich, künstlerisch ausgebildet, nur ein Anhang des Kopfes. Man darf gewissermaßen nicht sündigen gegen die Naturformen des menschlichen Hauptes, und man muss herausgestalten den ganzen Gliedmaßen- und Rumpforganismus aus dem, was veranlagt ist im Haupte. Das alles fordert zum Beispiel der Marmor, das alles fordert der Stein.

Arbeitet man in Holz, dann hat man die Notwendigkeit, gerade im entgegengesetzten Sinne zu arbeiten. Da hat man zu arbeiten aus der ganzen menschlichen Figur, aus der Bewegung der Gliedmaßen, aus dem Sich-Erfühlen des Rumpfes. Da darf man wagen, eine Armbewegung nach aufwärts, eine Armbewegung nach abwärts so zu gestalten, dass sie sich fortsetzt in einer asymmetrischen Stirn, wie es versucht worden ist bei dieser Gruppe. Das ist nur möglich geworden dadurch, dass die Gruppe eine Holzgruppe ist, dadurch, dass man, wenn man in Holz arbeitet, herausholt aus dem Material die Höhlung und nicht aufsetzt auf die Fläche dasjenige, was die Erhabenheit ist. Nur aus einem absoluten Drinnenstehen mit seinem ganzen Fühlen, vor allen Dingen in der Menschengestalt, kann ein solches Bearbeiten des Materials hervorgehen.

Das aber, was dann, wenn man plastisch die Menschengestalt arbeitet, am anschaulichsten hervortritt, tritt hervor in der ganzen Behandlung des Holzmaterials hier bei dieser Innenarchitektur. In Stein ausgeführt wäre das Fortschreiten der Säulen von den einfachsten Kapitell- und Sockelformen zu dem mittleren Komplizierten, dann wiederum das Zurückgehen zu dem Einfachen, also die Auflösung der allseitigen Symmetrie in einen entwicklungsgemäßen metamorphosischen Fortgang, in Stein wäre das alles ein Unsinn; denn der Stein fordert, dass er ein Umfassenderes ist, der Stein fordert die allseitige Symmetrie heraus. Allein das Holz gestattet dasjenige, was hier versucht wurde auszubauen. Wie gesagt, es hätte auch in Beton ausgeführt werden können, der ja durch seine Eigenart eben den Stein überwindet, nur würde dann die Form etwas anders aussehen. Aber das Holz gestattet, Entwicklung hineinzubringen in die Kapitellgestalt.

Und da möchte ich sagen, lag zugrunde die Umsetzung des Goethe’schen Metamorphosegedankens in das rein Künstlerische. Man muss allerdings sich ganz hineinleben in die schaffenden Mächte der Natur und muss herausschaffen die Formen aus den schaffenden Mächten der Natur, wenn man den Versuch wagt, aus den einfachsten Kapitellformen, die Sie hier bei den zwei Säulen am Eingange finden, zu immer komplizierteren Formen vorzuschreiten. Aber das hat sich ganz von selbst ergeben, das hat sich für die Empfindung ergeben, das ist nicht ausgeklügelt. Denjenigen Persönlichkeiten, welche in früheren Zeiten oftmals hier in diesem Bau geführt worden sind, denen ist gesagt worden: Die eine Säule bedeutet das, die andere Säule bedeutet das; denen ist gesprochen worden von Merkur-, Marssäule und dergleichen, und man hat in diesen Dingen, die eigentlich nur einer abstrakten Verständigung dienen, die Hauptsache gesehen. Die Hauptsache liegt nicht darin. Die Hauptsache liegt darin, wie das zweite Kapitellmotiv - aber jetzt für das künstlerische Empfinden - mit einer ebensolchen Notwendigkeit aus dem ersten hervorgeht, wie das höher gelegene Blatt oder die Blüte nach dem Prinzip des Naturwachstums hervorgeht aus dem tiefer gelegenen Blatt oder eben das Blütenblatt aus dem Laubblatt. Beim Formen eines solchen Begriffs sieht man die Natur theoretisch an. Hier handelt es sich darum, nichts von Theorie zu haben, sondern die Entwicklung zu erleben, wie die eine Form aus der anderen entspringt. Ich darf sagen: Alles das, was Sie hier an Kapitellen und Architraven sehen, ist durchaus rein empfunden, und derjenige, der darüber spekuliert, der darüber symbolische Interpretationen macht, der missversteht das Ganze.

Es ist aber merkwürdig, wie einem, wenn man selbst arbeitet, dieses Verwobensein mit den schaffenden Mächten der Natur Überraschungen bringt. Ich habe, als ich das Modell zu diesem Bau ausarbeitete (Abb. 22), lediglich im Gefühl gehabt, das eine Kapitell aus dem anderen hervorgehen zu lassen, das nächste Architravmotiv immer aus der vorhergehenden Metamorphose hervorgehen zu lassen, ebenso die Sockelmotive und so weiter. Da hat sich mir zunächst ergeben, dass jener Entwicklungsimpuls nicht dazu führt, dass immer nur von dem Einfacheren zu dem Komplizierteren fortgeschritten werde, sondern dass man das Komplizierteste eben gerade in der Mitte erreicht, wie Sie hier an den mittleren Säulen sehen, und dass man wiederum, wenn man gewissermaßen die Kompliziertheit bis zur äußersten Höhe getrieben hat, bis zur Kulmination getrieben hat, genötigt ist, ins Einfachere überzugehen. Daher sehen Sie hier nicht etwa in abstrakter Art eine solche Entwicklung angestrebt, die mit dem Einfachsten beginnt und zu dem Komplizierten vorschreitet, sodass das Letzte das Komplizierteste wäre, sondern Sie sehen die größte Komplikation der Motive in der Mitte.

Und dann darf ich Ihnen auch hier noch verraten, dass gewiss nicht etwa von vornherein angestrebt worden ist ein von Schlangen umwundener Merkurstab (Abb. 41, 42). Nein, das hat sich dem künstlerischen Erleben ergeben als etwas, was nicht anders sein kann, wenn man in der Entwicklung zu dem Komplizierten heraufsteigt und dann umkehren muss, um wiederum ins Einfachere hinunterzukommen. Ebenso war ich zum Beispiel überrascht, als — angekommen bei der siebenten Säule - ich fand, wie sich die Erhabenheiten der ersten Säule, wenn man sie wie einen Handschuh umgestülpt sich denkt - nicht geometrisch, aber künstlerisch umgestülpt —, genau in die Höhlungen der letzten Säule hineinpassen; wie wiederum bei der zweiten und sechsten Säule dasselbe der Fall ist, wie bei der dritten und fünften Säule dasselbe der Fall ist, und die vierte Säule in der Mitte steht.

Es ist nicht von vornherein irgendein abstrakt mystisches Prinzip der Siebenheit verfolgt worden; sondern gleich dem, wie man die Tonskala als eine siebengliedrige Wesenheit hat, mussten hier die Säulen so ausgebildet werden, dass gewissermaßen eine Oktave des Fühlens in der Form sich in einer Siebenheit vollendet. Denn das achte würde die Oktave sein; da hat es überzugehen in die andere Art des Empfindens, die man dann im kleinen Kuppelraume findet, der etwas enthält, was der Entwicklung als ein Aufnehmen entgegenkommt. Daher sind die Kapitellmotive der kleinen Kuppel (Abb. 58-63) nicht in ihrer Entwicklungsform gehalten wie hier, sondern sie sind mehr so gehalten, dass sie gewissermaßen das Glied eines einzigen Wesenhaften sind, das demjenigen, was als Entwicklung ihm zueilt, gleichsam die Arme erschließt.

Das alles sagt man sich aber nicht vorher, denn vorher hat man es mit etwas anderem zu tun, mit dem Leben in der Form, mit dem Leben in der Fläche selber. Das sagt man hinterher, um dasjenige, was geschaffen worden ist, einigermaßen anzudeuten. Nichts ist hier herausgewachsen aus irgendeiner neueren theoretischen Weltanschauung, nicht einmal aus der Ideenwelt der Geisteswissenschaft selber. Und es kann, ich glaube wenigstens bis zu einem gewissen Grade, erreicht werden, dass derjenige, der diesen Bau betritt, das Gefühl hat: Hier kann man zunächst all das, was man in den Kopf aufgenommen hat von geisteswissenschaftlichen Ideen und Gedanken, vergessen. Man braucht nicht darüber zu reden, sondern man kann es erfühlen, erfühlen aus den Formen und aus der Behandlung der Formen.

Sodass man etwa so empfinden kann: Wer den griechischen Tempel betritt, er fühlt das Umfassende dieses griechischen Tempels. Die Steinform waltet in Weisheit. Aus dem Makrokosmos heraus kommt die diesen Makrokosmos aufbauende Weisheit, stößt sich gewissermaßen durch die Ummauerung durch, arbeitet in den Stein-Erhabenheiten, in den Konvexitäten, und umschließt da den äußerlich ruhenden, nur im Geiste für die Welt tätigen Gott. Dasjenige, was mit einem gotischen Bau angestrebt wird, man könnte es in einer ähnlichen Weise empfinden. Es ist die Gemeinde mit ihrem Gruppenseelenhaften, die eigentlich, indem sie versammelt ist in dem Dom, dasjenige um sich hat, was sie selber gebaut, gemauert, gemeißelt, geschreinert und so weiter hat. Man hat immer das Gefühl, wenn man einen gotischen Dom betritt, dass man es, im Gegensatz zu dem griechischen Tempel, der aus einem rein aristokratischen Denken entsprungen ist, zu tun hat beim gotischen Dom mit einem Stände-Denken, mit der Gliederung des mittelalterlichen Lebens, das sich ausspricht durch das Suchen nach dem Menschtum, das auch in seinen Formen dieses Suchen nach dem Menschtum durchaus ausdrückt.

Diejenigen Menschen, die durchaus nicht sich entschließen können, so etwas unbefangen anzusehen, sprechen von dem Tempel von Dornach. Das Gegenteil irgendeines Tempels ist das, was hier aufgebaut worden ist. Nichts Tempelhaftes ist hier, nichts irgendwie, was auch nur mit der Kirche, mit dem Domhaften in eine Beziehung gebracht werden kann. Und wer vom Tempel von Dornach spricht, der drückt damit nur aus, wie er mit seinem ganzen Empfinden stehen geblieben ist bei der griechischen Architektur, noch nicht einmal bis zur Gotik vorgedrungen ist. Hier aber musste das in Angriff genommen werden, was Formen schafft, welche im Grunde genommen nur die Fortsetzung desjenigen sind, was hier gesprochen, was hier musiziert, was hier deklamiert, was hier etwa sonst künstlerisch dargestellt wird. Und so der Redner hier auf dem Pulte steht, wie oben die Orgel ertönt, wie die rezitatorischen Töne durch den Raum vibrieren, so muss dasjenige, was da aus dem Worte, aus dem Tone, aus dem Gedanken stammt, weitersprechen durch die Umrahmung, durch die Einfassung hindurch, die keine Einfassung ist, sondern die nur fortsetzt das gesprochene, das getönte Wort. Wir haben es im griechischen Tempel mit einer Einfriedigung zu tun; wir haben es hier mit einem Sich-Aussprechen zu tun. Daher muss vor allem die ganze Form so sein, dass sie liebevoll aufnimmt, was hier geschieht, dass sie es aber nicht abschließt, sondern dass dieser Bau dasteht als ein Wahrzeichen dafür, dass dasjenige, was hier in Dornach erarbeitet wird, hinausdringen soll in die ganze Menschheit.

Wenn Sie daher studieren, was hier an Säulen, mit der Rückwand zusammen, die Umschließung bedeutet, so werden Sie sehen: Es kann nun das Ganze wiederum so empfunden werden, dass man nirgends das Gefühl hat, man sei eingeschlossen und man rede nur bis zur Wand hin; sondern man hat das Gefühl: Man redet, und die Formen der Wand, diese Kapitelle, diese Architrave, diese Säulenformen nehmen auf die Schwingungen des Wortes und wollen sie eigentlich hinaustragen in die Welt, wollen nicht abschließen, sondern wollen künstlerisch durchsichtig sein. Und wie das Holz hier in solchen Formen geschnitten ist, die das Holz künstlerisch durchlässig machen, so ist angedeutet in diesen Fenstern, ich möchte sagen auf eine mehr naturhaft materielle Weise, wie dasjenige, was hier im Innern ist, zusammenhängen soll mit dem Äußeren. Diese Fenster sind für sich ja keine Kunstwerke; diese Fenster, deren Technik im Wesentlichen eine Glasradiertechnik ist, sind nur dann Kunstwerke, wenn das Sonnenlicht durch sie hindurchscheint, wenn eine zwischen demjenigen, was aus dem Glase herausgekratzt worden ist, und dem durchscheinenden Sonnenlichte. Das schließt nicht ab, das lässt die Sonne herein, das ist der lebendige Vermittler mit dem Ganzen, mit dem Lichte, das den Kosmos durchflutet, und ist nur etwas, wenn man es in Zusammenhang mit diesem Lichte betrachtet.

Geht man so künstlerisch empfindend vor, dann darf man es auch wagen, die Motive auszubilden, die in diesen Fenstern sind.

Ich kann natürlich auf Einzelheiten nicht eingehen, aber ich verweise Sie auf jenes blaue Fenster dort (Abb. 111), wo Sie in den beiden Flügelfenstern die menschliche Gestalt sehen, die menschliche Gestalt in zwei Situationen. Das eine Mal leben im Menschen alle jene Eigenschaften, die im Jäger leben, wenn er anlegt auf das Tier, welches er herunterschließen will. In dem, was ausgekratzt ist aus dem Glase, finden Sie dieses ganze Innere des Menschen dargestellt, finden Sie alles das, was in ihm lebt, in das Figurale gegossen. Man kann, wenn man zu einer bestimmten Etappe innerlichen Erlebens kommt, nicht anders, als Gestalt geben dem, was als Leidenschaft im Innern lebt. Und wenn Sie sich dann wiederum metamorphosisch fortgeschritten denken das ganze Bild, so haben Sie Folgendes im rechten Flügel: Der Mensch ist fortgeschritten von der Absicht, den Vogel herunterzuschießen, zu der Ausführung der Tat: Er hat angelegt, er schießt. Was früher vorgegangen ist, verwandelt sich in das andere, was dann im rechten Fenster aus dem Glase herausgekratzt ist und mit dem Sonnenlichte zusammen erst das Kunstwerk gibt. So würde jedes einzelne Fenster behandelt werden können. Aber es handelt sich hier nicht darum, dass man wiederum mit Interpretationskünsten kommt, sondern dass man sich dem, was auf dem Glas ist, empfindend hingibt. Gerade wenn man Interpretationskünste anstrebt, so übersieht man die eigentliche künstlerische Absicht darin.

Und wenn Sie diese Kuppelmalerei ansehen (Abb. 57), wenn Sie sich ansehen, wie aus der Farbe herausgeholt ist alles dasjenige, was in die kleine Kuppel hineingemalt ist, dann werden Sie auch da das Bestreben haben, hinauszuempfinden aus dem abgeschlossenen Raum in den Kosmos. Da ist so gemalt, dass die Malerei auf der Fläche sich selber aufhebt, dass man eintritt wie durch eine Pforte in ein Lebendiges. Das kann man aus der Farbe hervorholen, wenn man lebendige Farbenempfindung hat. Es gibt natürlich Menschen, die da droben lieber naturalistische Figuren sehen würden; dadurch würde ihnen die Unbequemlichkeit erspart, die Dinge erst zu empfinden. Denn das, was man an einer schönen — was man so «schön» nennt — naturalistisch gemalten Menschenfigur empfinden kann, das hat man ja von Kindheit an schon empfunden, und es ist bequem, das wiederzusehen. Wenn man aber hierherkommt, dann hat man nicht Veranlassung, dasjenige, was man seit der Kindheit empfunden hat, hier wiederzufinden und zu sagen, das sei ja dem oder jenem ähnlich, sondern hier handelt es sich darum, gewissermaßen in kurzer Zeit alle jene Lebendigkeit im Innern durchzumachen, die man sein ganzes Leben lang durchgemacht hat, um so in Lebendigkeit aufzufassen, was aus den Farben und aus den Formen herauskommt - die ja der Farbe Werk sind; nichts anderes wollen sie sein -, und die Empfindung zu haben: Es schließt einen nicht ab, es trägt dasjenige, was man hier empfindet, in die ganze Welt hinaus, es verbindet einen mit der Welt. Nichts ist hier an diesem Bau anders gedacht denn als eine organische Bildung.

Das ist allerdings ein Wagnis gewesen, die mechanischen Bauformen überzuführen in das Organische. Indem man ein Organisches ausbilden will, muss alles so sein, dass es an dem Orte, wo es vorkommt, nicht anders sein könnte. Nehmen Sie nur so etwas Unbedeutendes wie ein menschliches Ohrläppchen, das ist gewiss am menschlichen Organismus etwas sehr Unbedeutendes. Nach dem aber, wie der ganze Organismus eines Menschen ist, muss sich an diesem Orte hier dieses ganz bestimmt gestaltete Ohrläppchen bilden, und es könnte sich natürlich nicht ein ähnliches Organ, sagen wir, an der Spitze des kleinen Fingers oder anderswo entwickeln. An seinem Orte hat jedes seine Form.

Das ist hier als Baugedanke entwickelt worden. Alles, was Sie hier (Abb. 27) geformt sehen, ist herausgedacht aus dem Ganzen, ist hingedacht und hinempfunden an den Ort, wo es gerade steht. Die Säule ist aufgelöst so, dass man der aufgelösten Säule in ihrer Form das Tragende ansieht. Wenn Sie draußen am Eingang irgendein Motiv sehen, so werden Sie seinen Formen ansehen: Dies ist gegen den Eingang zu. Treten Sie ein paar Schritte weiter hinein, so ist das, was die Säule zu tragen hat, nicht mehr in derselben Weise da. Wenn Sie aber von der Außenwelt her hereingehen in das, was ein solches Säulengebilde zu tragen hat, es müsste das Lastende und Schiebende des ganzes Baues gegen jede Säulengliederung hin empfunden werden und wiederum das Entlastende gegen die Außenwelt zu. Eine innere Dynamik, die ins Leben strebt, das ist es, was hier gesucht worden ist. Und wir leben einmal in einer Zeit, in welcher auf allen Gebieten des menschlichen Schaffens eine solche Metamorphose dessen angestrebt werden muss, was mit Recht früher empfunden worden ist.

Ich muss zurückdenken an Schlegel, der - hinblickend auf die vergangenen Bauformen, welche die «Renaissance-Menschen» immer wieder heraufholen möchten - das schöne Wort geprägt hat: «Die Baukunst ist eine gefrorene Musik.» Ein schönes Wort für all das, was in der Baukunst vorangegangen ist, und ein außerordentlich treffendes Wort. Man hat das Gefühl, dass in diesen Baugedanken eine Musik lebt. Wie könnte man schöner Musik schauen als in den Bauformen des griechischen Tempels! Wie könnte man Bach, prophetisch vorausgeschaut, anders empfinden als in den Formen des gotischen Domes! Die Fuge, sie lebt schon im Spitzbogen. Da war sie eingefroren, und Friedrich Schlegel hatte recht, die Baukunst, die er kannte, eine gefrorene Musik zu nennen.

Aber wir leben heute in einem bedeutungsvollen Momente des menschlichen Werdens. Wir leben in dem Momente, wo alles Schaffen andere Gestalt annehmen muss. Und so müssen wir auch die gefrorene Form der Baukunst zum Auftauen, zum Schmelzen bringen. Aber sie würde in das Unbestimmte zerfließen, wenn sie bei diesem Schmelzen nicht durchseelt würde. Und so müssen wir einfach zu der gefrorenen Musik eine auftauende Musik haben, die uns anschaut, fordernd: Gib mir Seele! Das, sehen Sie, ist etwas von dem Baugedanken von Dornach, was da aus der Menschheitsentwicklung heraus sprach: Taue mich auf, ich bin die gefrorene Musik! Aber ich würde ins Nichts zerfließen, wenn im Auftauen nicht in alle Formen die bewegte Seele, die innerlich intensiv bewegte Seele hineinführe. Nicht bloße Symmetrie-Proportionalität soll in den Formen leben, nicht bloß das, was das eine Kapitell in Symmetrie und Proportionalität neben das andere stellt, sondern lebendige, intensive Bewegung, die das eine Kapitell aus dem anderen hervorwachsen lässt wie ein Blumenblatt aus dem anderen, die Form metamorphosisch verwandelnd.

Ich weiß alles, was man gegen dieses Überführen des Baugedankens aus dem DynamischMathematischen in das Organisch-Lebendige haben kann, und ich verstehe jeden der von den am Alten hängenden Künstlern nach dieser Richtung gemacht wird; ihn nachfühlen. Aber es musste einmal ein Anfang gemacht werden mit dem, was die Zeit aus ihren Tiefen heraus von uns Menschen in der Gegenwart und für die nächste Zukunft fordert. Und so wird auch nur derjenige diesen Bau fühlen, der, indem er ihn erlebt, ihn als ein Bedürfnis seiner eigenen Seele erlebt, die sich zu den Forderungen der Gegenwart und nächsten Zukunft durchgerungen hat. Gewiss, es ist noch vieles unvollkommen, und ein zweites Mal aufgeführt, würde dieser Bau ganz anders aussehen. Aber trotzdem können Sie wenigstens an dem Versuch sehen, wie bis ins Kleinste hinein versucht ist, das DynamischMathematische ins Organische überzuführen.

Sehen Sie sich die Heizkörper (Abb. 26) an. Sehen Sie sich an, wie sie aus einer organisch-lebendigen Elementarform heraus geschaffen sind, so wie wenn gewisse Kräfte, die geheimnisvoll im Erdeninnern wirken, über die Oberfläche der Erde hin weiterwirken wollten. Hier wurde Ihnen vor einigen Tagen ein Hinweis gegeben, wie in der Erde auf geheimnisvolle Weise die Elektrizität weiterwirkt, wenn man das, was nur durch einen Draht vermittelt ist, zum Stromkreislauf schließt durch die Erdleitung, wie gewissermaßen die ganze Erde in ihren Kräften dasjenige ersetzt, was in einer zweiten Drahtleitung da sein müsste. Oh, in dieser Erde ruht viel Geheimnisvolles drinnen. Aber das, was geheimnisvoll in der Erde drinnen ist, man kann es - nicht verstandesmäßig, aber empfindend - enträtseln. Wenn man es umschafft zu Formen, die allerdings nicht sklavische Nachahmungen von Tier- oder Pflanzenformen sein sollen, sondern die ganz selbstständige Formen sind, dann bekommt man sie so, dass man sie lebendig empfindet. Man kann dann einen breiten, niedrigen Ofenschirm bilden und macht dabei die Form anders, als wenn man einen schmalen, hohen Ofenschirm macht. Man hat das metamorphosierende Prinzip in sich; es geht in die schaffende Hand über.

Selbstverständlich sind das alles Dinge, die der Mensch der Gegenwart vielleicht noch als ihn abstoßend empfindet. Er mag es tun. Diejenigen, die am Alten hängen, haben immer das, was sich hereingestellt hat als etwas Neues, abstoßend empfunden. Aber solch ein Versuch muss eben einmal gewagt werden. Hier wurde er nicht einmal aus dem Abstrakten heraus gewagt, sondern er wurde unternommen, weil eben ein zweiter, ein künstlerischer Ast aus denselben Wurzeln hervorgehen wollte, aus denen die Geisteswissenschaft selber hervorgegangen ist. Und ich möchte es noch einmal betonen: Kein einziges Symbolum finden Sie hier in diesem Raum. Wenn Ihnen irgendetwas hier als Symbolum erscheint - es könnte Ihnen höchstens, wenn später der Vorhang aufgemacht wird, das fünfblättrige Blumenblatt da hinten im kleinen Kuppelraum (Abb. 55, 57) wie etwas erscheinen, was symbolisch gemeint sei -, doch nichts ist symbolisch gemeint. Ebenso wenig, wie die Blumenblüte in ihrer Fünfzahl symbolisch ein Pentagramm darstellt, ebenso wenig ist hier irgendetwas symbolisch gemeint. Organisch aber, bis zu diesem Orgelraum (Abb. 28-30) dahinten, ist alles so versucht, dass jede Einzelheit, jede künstlerische Linie aus der Form des Ganzen heraus gedacht ist.

Wenn dieser Baugedanke von Dornach hier von mir so charakterisiert werden durfte, so darf das selbstverständlich nicht anders sein, als dass ich zu gleicher Zeit hinzusetze, es sei das hier ja nur der Anfang eines Versuches. Und Sie können überzeugt sein davon: Diejenigen, die hier an diesem Bau arbeiten, diejenigen, aus denen dieser Baugedanke entsprungen ist, die denken nicht unbescheiden darüber. Die denken darüber so, dass sie ganz gewiss zwar beibehalten Impuls, Prinzip und Stil, das Wesentliche also, auf was es ankommt, doch etwas ganz anderes schaffen würden, nachdem sie gelernt haben, was im Schaffen an diesem Bau gelernt werden kann. Gelernt konnte hier viel werden. Denn man lernt wahrhaftig nicht gründlicher, als wenn man gezwungen ist, das, was in der Seele lebt, in die konkrete Tat ausfließen zu lassen. Abstrakte Ideale aushecken, das kann man mit einer großen Vollkommenheit verhältnismäßig leicht. Ist man aber genötigt, schon bei den allerersten Schritten, welche eine Idee, ein Impuls innerlich in der Seele annehmen, diese Idee, diesen Impuls so auszugestalten, dass er im äußeren Material weben kann, damit das Werk, in welchem er sich verkörpert, nicht strohern allegorisch wird, dann fordert das etwas ganz anderes im inneren Erleben, dann fordert das eben Verwachsensein mit dem Weltgedanken, mit den Weltimpulsen, mit demjenigen, was in der Welt lebt.

Deshalb nahmen die Griechen, die über die Welt nicht bloß denken, sondern auch empfinden konnten, das Wort «Kosmos», mit dem sie das Weltenall bezeichneten, nicht von der Theorie, sondern von der Empfindung her. In dem Worte «Kosmos» liegt ja die Schönheitsempfindung, die in uns erregt wird, wenn wir das äußere Weltall betrachten. Aber derjenige, der heute einen Baugedanken in Realität in seiner Seele trägt, der muss miterleben können und auch kosmisch künstlerisch ergreifen können die Menschheitsentwicklung selber. Wir versetzen uns hinein in den Anblick des Portals eines griechischen Tempels. Wir treten ein in den Tempel. Wir erleben die Formen, die uns da umgeben, als Umfriedung des Gottesbildes. Wir empfinden etwas wie in Form gegossene Weisheit, jene Weisheit, welche die ganze Welt durchströmt und die einmal in äußeren Formen künstlerisch herauskommen musste, die empfunden werden musste und die wohl in höchster Art empfunden wurde, als der Tempel als Wohnhaus des griechischen Gottes geschaffen worden ist.

Ein anderes Material müssen wir haben als den Stein, der uns in seinen Erhabenheiten ausgestalten lässt die Weltenweisheit, ein anderes Material müssen wir haben, wenn wir aus dem Innersten des modernen Menschen heraus arbeiten; denn da muss eine andere Kraft ins Weltenall hinausstrahlen, als es die Weisheit ist. Die Weisheit empfangen wir; die strahlt uns entgegen aus dem, was wir der Fläche an Erhabenheiten, an Konvexitäten aufsetzen. Stehen wir dem weichen Holz gegenüber, dann höhlen wir hinein in das weiche Holz dasjenige, was in uns selber lebt, da übergeben wir dem Kosmos etwas von uns. Wir dürfen aber als Menschen, wenn wir nicht sündigen wollen wider den ganzen Geist des Weltenbaues, nichts anderes hineintragen, als das, was auf dem Strome der Liebe in das Weltenall hineingetragen wird.

Und derjenige, der künstlerisch empfinden kann, empfindet, wenn er aus der Fläche heraus für den Marmor formt, wie die Weisheit ihn überkommt in seinem Bewusstsein, wenn er den Baugedanken des Marmors ausführt. Derjenige, der einen solchen Baugedanken wie den hiesigen ausführt, empfindet, dass er in wirklicher Ergebenheit gegen die Größe des Weltenalls das bilden muss, was sich bilden lässt, wenn man in das weiche Holz hineinhöhlt, was in der Konkavität leben kann. Da hineinhöhlen darf man nur, wenn man in Liebe zum Weltenall hineinhöhlt. Niemand dürfte eigentlich eine Erhabenheit auf einer Fläche ausbilden, ohne überwältigt zu sein von dem weisheitsvollen Gehalt des Weltenalls. Niemand darf es wagen, die Sünde zu begehen, dem Stoff das eigene menschliche Wesen einzuprägen, den Stoff auszuhöhlen, der es nicht in Liebe zum Weltenall tut. Das aber sind die zwei Pole aller Menschheitsentwicklung: Idee oder Weisheit und Liebe. Es klingt uns entgegen aus Goethes Sprüchen in Prosa wie eine Grundlösung des Weltenrätsels, wenn Goethe sagt: Das Höchste, das der Mensch empfinden kann, ist der Zusammenklang von Idee und Liebe.

Dass dieser Zusammenklang hier zunächst nur, ich möchte sagen, wie stotternd erreicht worden ist in dem, was wir jetzt konnten, das ist uns bewusst. Aber es möchte dieser Bau nach den Intentionen, aus denen sein Gedanke geflossen ist, auch nichts anderes sein als ein Keim. Ein Keim aber darf nicht nur nach dem beurteilt werden, als was er sich zunächst darstellt, ein Keim muss beurteilt werden nach dem, was aus ihm herauswachsen kann. Damit einmal ein Anfang gemacht werde zu dem Wachsen dieses Keimes, sind diese Kurse veranstaltet worden. Und wir haben Sie gerufen aus dem Grunde, weil Sie Teile dieses Dornacher Baugedankens sind. Denn was ich Ihnen auch erzählen könnte über den Baugedanken von Dornach, es müsste alles ein Unfertiges sein, weil dieser Baugedanke nur vollendet wird dadurch, dass diejenigen, die ihn empfunden haben, hinausgehen in die Welt und - jeder an seinem Ort - dasjenige vollbringen, wozu dieser Baugedanke mit allem, was in dem Bau gepflegt werden kann, der Keim sein soll. Ich kann Ihnen nur von etwas Unvollendetem sprechen.

Fertig machen dasjenige, was hier gewollt ist, das kann man nicht in Dornach, das können nicht jene, die selbst noch so vollendet hier arbeiten würden; das können wirksam Sie, indem Sie hinausgehen in die Welt und vollenden, was hier zwar angedeutet, aber doch unvollendet bleiben muss. Nicht zur Bewunderung, nicht zur Bewertung des Baues sind Sie aufgerufen, sondern zur Fertigstellung dieses Baues, dazu, dass Sie das weitere Material sein mögen, in welchem der Weltengeist selber arbeitet, in welchem er von Ihnen in Freiheit ergriffen wird, auf dass in der heutigen sozialen Not, in dem heutigen entscheidenden weltgeschichtlichen Augenblicke, das getan werde für die Weiterentwicklung der Menschheit, was nicht zur Barbarei, sondern zu einem neuen lichtvollen Aufstieg der Menschheitsentwicklung führt. Das möchte man, dass die Wände, die Säulen, die Fenster, die Kuppelräume zu Ihnen sprechen: Werden Sie die Vollender des Baugedankens von Dornach! Denn in diesem Sinne haben wir wahrhaft auf Sie gerechnet.