The Building Concept of the Goetheanum

GA 289

9 October 1920, Dornach

Translated by Steiner Online Library

2. The Artistic Impulses Underlying the Building Idea

In today's lecture, my task will be to contribute something to the understanding of what lies in the artistic impulses that carry the building idea of Dornach, in order to then develop this building idea in more detail in the next of these lectures. It will be necessary for me to say something about these artistic impulses, so to speak, because strong misunderstandings have spread about them.

The point is, and this is clear from what I said here eight days ago about the development of the Dornach building from our entire anthroposophical movement, that the Dornach building should in no way create something that could be called the carrying of abstract spirituality into what is actually artistic. The Dornach building should be created entirely by artistic forces. And this building should mark the beginning of a development towards this goal, so that what works in spiritual science as a spiritual being can also flow out, stream out into artistic forms, into artistic designs and so on. This is something that had to be fought for against certain tendencies that very easily run in the opposite direction, especially in such a movement as anthroposophy.

It is very easy for all kinds of mystifying elements to enter into such a movement. These elements push towards the abstract through a false mystification, and which actually – because the artistic element must express itself in the shaping and forming of the external – bypass this artistic element and strive towards the symbolic, towards the allegorical. They want to keep the spirit in its abstract form, so to speak, and see in the outwardly shaped and formed only a symbolic illustration of the spiritual.

This leads to a killing, a paralysis of everything truly artistic. In this direction, due to the penetration of false mysticism from the theosophical into the anthroposophical movement, one has had to experience all sorts of things. For example, a play like “Hamlet”, which is an artistic creation, was interpreted allegorically and mystically, so that one figure was understood as the spiritual self, the other as the astral body, and so on. There is endless allegorizing among those who would like to profess such a spiritual movement, and I once had to experience the following, for example: When I tried to discuss the well-known painting 'Melancholy' by Dürer in such a way that I traced everything that lives in this painting back to the chiaroscuro and showed how Dürer wanted to penetrate the secrets of the chiaroscuro, of the chiaroscuro, to contrast the light with the dark, the darkness with the light, in the most varied of ways, a voice was heard from the audience saying, “Yes, but can't we understand this picture on an even deeper level?” The deep interpretation was obviously sought in the fact that one wanted to extract from the artistically captured chiaroscuro an abstract-allegorical interpretation of what is depicted in the picture, which Dürer has already forbidden by placing the polyhedron in the picture to suggest how important it was to him to express the chiaroscuro variety that becomes visible when you compare differently directed surfaces, differently positioned surfaces of a polyhedron or the different surface layers of a sphere with any spreading light. That it is infinitely deeper to look into this working and weaving of light and darkness and to spread one's own spirit over this weaving of light and darkness, that for the one who feels artistically, it can be infinitely deeper than the abstract-intellectual allegorical interpretation of such images, such an interrupter had no understanding.

And so what is present in this building had to be seen as an initial, weak attempt, in many respects fought for in the face of those aspirations that strive towards allegory and symbolism. These can be seen sufficiently when one enters some particularly solemnly decorated rooms where Anthroposophical spiritual science is practised and sees that attempts are being made to begin with colours and all kinds of paintings and drawings, but that these attempts ultimately leads to nothing other than offending every artistic feeling by painting a hideous rose cross, when what matters is only the allegory of showing some symbolism in seven roses painted in a certain way on a cross. I must mention this so that, if anthroposophically oriented spiritual science is also to show its artistic fertility to the world, it is known that what is attempted artistically must not be confused with all the abominations that easily arise from symbolizing and allegorizing, especially on such mystical ground as I have indicated.

It is absolutely essential that the true spiritual scientist should realize through direct insight what the essence of the ideal consists in, so that he can find the transition from the ideal to what must be expressed in prose words, even though these prose words are only an inadequate means of revelation for the rich revelation of the spiritual world itself, and that this necessary prose presentation, which must also take on certain forms if it is to do justice to the spiritual world, is sharply contrasted with the actual artistic presentation, including that of the supersensible vision, which has nothing of symbolizing or allegorizing in it.

That is why I had to point out in the lecture I gave to you on declamation and recitation that it is nonsense to fantasize and allegorize all sorts of things into my mystery dramas that are actually anthroposophical theory. The point of the dramas is to be understood artistically; and I myself, if I may make this personal comment, suffer the most unspeakable pain when someone presents me with abstract concepts that are supposed to “explain” these mystery dramas. These mystery dramas have been seen and experienced down to the last word, down to the tone of voice, as they stand, and the one who introduces allegorization does not understand them. He cannot really bring out the measure of super-sensibility that lies in them, for he only imprints the intellectual concepts into what should actually be experienced in the artistic sense. And so it is with everything else that is to arise artistically from those impulses from which spiritual science itself arises.

I would like to say it clearly, although it may sound a little pedantic: no art can of course arise from spiritual science itself, as it is communicated in words; only allegory and symbolization can arise from it. But from those spiritual impulses that stand behind spiritual science, that drive spiritual science itself out of themselves like a branch, from those, as another branch from the same origin, artistic creation also arises. Therefore, those who understand spiritual science in the abstract and then want to translate it into art will never be able to create anything other than straw-like allegories or lifeless symbols.

It has been said many times that symbols and allegories can be found in this building. If you look at the building properly, you won't be able to find a single symbol or allegory in it. Everything is meant to be – although some things have been left in initial attempts – in such a way that it has flowed into the form, the design, the color. And because misunderstandings can easily arise in this regard, I would like to discuss a few artistic matters with you today, so that, as I said, I can get to the actual building idea next time and characterize it in very specific terms.

I would like to assume that, when we once had to perform that scene from the second part of Goethe's “Faust” in the carpentry workshop, in which the Kabirs appear, I tried to create the three Kabirs plastically from the supersensible vision that arises when one tries to penetrate the mysteries of Samothrace. So I tried to visualize these Kabirs in order to be able to bring them on stage. Now these three Kabirs were there in three dimensions. Then a personage who was very close to our movement wanted to give some other people an idea of these Kabirs, who could not see them here, or who wanted to have a souvenir of the way in which the Kabirs were vividly reconstructed here, and the question arose as to whether these Kabir sculptures should be photographed.

For someone who has a feeling for sculpture, however, every photograph of a sculpture is a killing of the actual sculptural work of art. And so I decided to simply reproduce these Kabir statues in a drawing, in chiaroscuro, that is, using a different technique. So from the outset they were conceived two-dimensionally on the surface, and so it was possible to photograph them and disseminate them through photography. So you see: if you really stand on the soil of those life forces that pulsate in spiritual science, then above all you acquire a truly artistic feeling for the artistic means you use, and you acquire emotionally, not intellectually, what lives in existence.

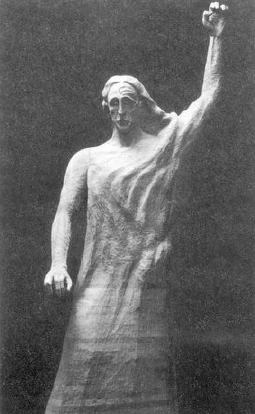

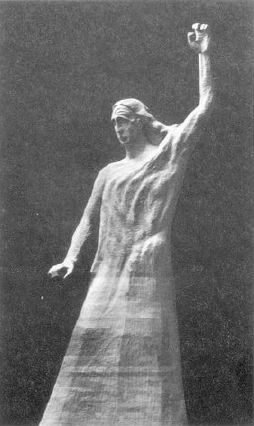

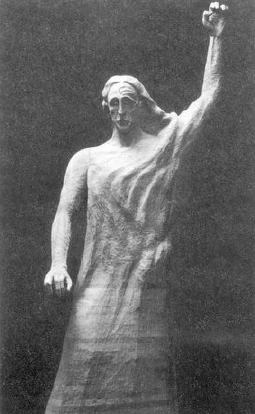

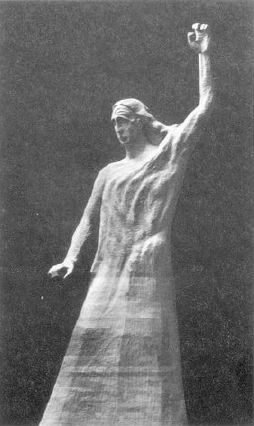

Let me mention the following example, which leads us more into the intimacies of the artistic empathy of the world process, which we then try to shape. Let us assume that one wanted to create a kind of sculptural representation of humanity, as I attempted in my sculptural group, which includes a figure similar to Christ (Figs. 94-98). If you want to create a sculpture of this representative of humanity, you would be led to feel quite differently about what is present in the formation of the head than about what is present in the rest of the human being's form, which lives outside the head.

In sculpting, you feel what appears as a huge difference in the human being. In sculpting, where one is dealing with the shaping of surfaces, one feels that a formative impulse must be at work in the head, which, as it were, pushes inwards, draws away from the outside, but which shapes from within; and one feels that in the rest of the human being, one encounters that which is shaped in precisely the opposite sense. It is not so important to say that one thing happens from within and the other from without – that would lead to an abstract, intellectual description again – but rather it is important to have the opposite feelings when developing any form out of the depths of the world process develops some form that can only be shaped from the inside out, or when one takes out a form that can only be shaped from the outside in, in which one can see, as it were, how the external world forces concentrate and shape from the outside in.

If one continues in this feeling and sensing, then one comes to understand how, through having different feelings for the head than for the rest of the organism, one experiences something as a sculptor that is neither gravity nor vertically acting buoyancy nor even spreading force. Pure spreading force is what we feel in the light. Gravity alone is what we feel in our own weight and experience in particular in the aging of the human being, if one can take a look at this aging in true introspection. Of these two forces, gravity and buoyancy, one senses a kind of interaction in such a way that, I would say, the buoyancy forces, those forces that tear the plastic away from the earthly, can be felt more in the head, and the forces that work upwards from the earth's gravity and, as it were, drive the body upwards, these are felt more in the shaping, in the plastic formation of the rest of the body.

But, my dear attendees, when one has really felt this, and – especially when one has metamorphosed this feeling into artistic creation – when one really lives not in an abstract idea, but in this feeling and endeavors to bring into the material that which one feels there, then one feels a strong difference... [gap in the shorthand]. For example, in sculpture there is something to be sensed, such as the balance of two forces, of which the sculptor himself need know nothing. Even someone who knows about such forces as spreading force, gravity and buoyancy force, completely forgets it in sculpting; it is none of his business there, he lives purely in feeling the spreading of the forces of the surface, in feeling how the surface expands in space, or in shaping the surface itself. If you have not appropriated anything abstractly conceptual – that is, if you can completely shed the cloak of the ideal when you immerse yourself in artistic creation – then, in a sense, you become a different person emotionally when you immerse yourself in artistic creation; then you also acquire a feeling for the diversity of artistic means of expression.

And when one moves from working with sculpture to working with painting, one comes to say to oneself: All that one has to say about sculpture in terms of the way in which forces acting vertically and in the direction of propagation interact, of heavy elements and light elements, all that one has to have put aside when dealing with color and its nuances in painting. Because there it is about creating not out of the line, not out of the form, but out of the color, so that one completely stops feeling differently towards the head than towards the rest of the organism, as the sculptor does. In painting, one feels that difference disappear that arose for the sculptor between the head and what is not the head in a human being. This completely balances out and becomes something completely different, an inner intensity that cannot be represented by a contrast of lines, but can only be represented by penetrating into the intensity of the color nuances, so that it is not possible to go into detail, for example, on what still stands out very strongly in sculpture.

And if you want to overcome it, you can only do so if you push the sculpture to a certain degree of consciousness, as I did with my central group for this building. But if you move on to painting, it is a matter of thoroughly rejecting any thinking in lines and moving on to the feeling that creates purely from color. And however strange it may seem to someone who speaks of a spiritualization of art in a falsely abstract sense, it must still be said: for someone who thinks in terms of painting, the most important thing is that there is a certain color nuance at a certain point on a certain surface and that, when one moves from this color nuance to another point on the surface, other color nuances are there. It is about creating from color.

In this creative process, however, the artist is supported by what I would call the experience of color, the experience of blue, the experience of yellow, the experience of red. What the artist has, in experiencing yellow and red as if they were attacking him, and experiencing blue as if he had to chase after it with his soul, as if he had to expand himself, is what transforms into creativity within him and what then gives him the opportunity to transform the sensation into what is to become a work of art. If, for example, one is faced with the task of painting any surface, then it is a matter of nuancing between so-called light, warm colors and dark, cold colors. If one has the color experience, one can create out of this color experience, just as the musician creates out of the sound experience. Then it is a matter of the form arising out of the color itself, so that one does not draw and then smear color into the spaces created by the drawing spaces that arise through drawing, smearing the color in, but rather it is a matter of starting from the color experience and allowing the line experience, the form, to arise from the color experience. That is why I said at one point in the first of my mystery dramas - that is, I had a character say it, to whom I put it in the mouth - that the form must be “the color's work”.

Fundamentally, we must be aware that all drawing and all thinking in drawing is actually a lie compared to painting. For example, when I see the blue sky, with the sea-green of the surface of the sea below, I have the blue of the sky above, the green of the sea below, and the line of the horizon simply arises from seeing, from the experience of color. And I am actually lying when I draw a horizon line that is not actually there (Fig. 114). This must now be thoroughly examined, otherwise one will not be able to enter into that world, which can be experienced through all the means of artistic expression, through the colors and their nuances, as well as through the concepts and ideas, if these concepts and ideas are really rooted in the spiritual and are not abstracted from ordinary human consciousness.

You see, here it is not so much a matter of expressing spiritual science in all kinds of forms, but rather of gaining impulses for artistic observation, which are just as necessary in the course of human development as spiritual science itself. But they are required as something special. It is the case that on the one hand there is the spiritual-scientific stream and on the other hand there is the artistic stream, which in a certain way must now also take on new forms. Therefore, I say to everyone who stands before this group, which is to become the central group here: One can feel something in the central figure like the Christ-figure, but it must be felt, it must not be thought that the name Christ is there. It will certainly not be written on the outside, but it does not even have to be thought, rather, the intuitive experience must take place within us, which draws our attention to how we must look at the matter, so that we develop reverence, develop high regard, develop the intuitive perception of the depths of the human being. So there should be nothing but feeling, nothing but experiencing in feeling, the same feelings that we experience, for example, when we immerse ourselves spiritually in the figure of Christ. But everything we experience spiritually when we immerse ourselves in the figure of Christ through spiritual science must not be carried over into what is formed plastically or pictorially. What is formed plastically or pictorially must be born out of form, out of line, out of surface. And this life in form, in line, in surface, in color, in word itself, is what later develops such forms, such painting, as it is to appear here in this building before you.

What I have said now has little to do with the building itself, but only with the artistic attitude and artistic feeling that underlies the entire building idea of Dornach. It should always be borne in mind that it is at the beginning of the development of that architectural style, that artistic language of form, which can be expected to flourish in a special way in the future. Because I would not rebuild this building in the same way a second time. Not because I consider the artistic attitude on which it is based to be misguided – that is not the case – but because everything that is alive is also constantly evolving, so that a second time all those mistakes would be avoided and everything that could be said in terms of impulses for perfection could be taken into account. But I see all this myself and take it much more seriously than those who often call themselves critics of the building. I know the mistakes very well today and know what could be avoided if the building were to be rebuilt, and what could be brought into it if it were to be rebuilt. And it is necessary that all the details of the building idea from Dornach be taken up in this way.

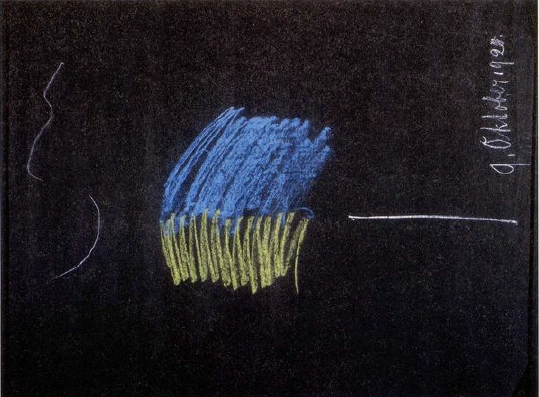

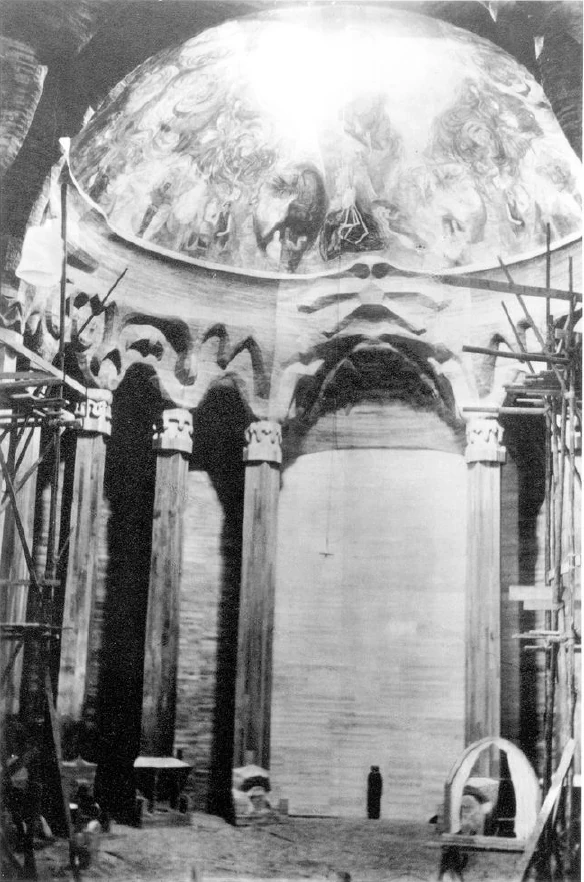

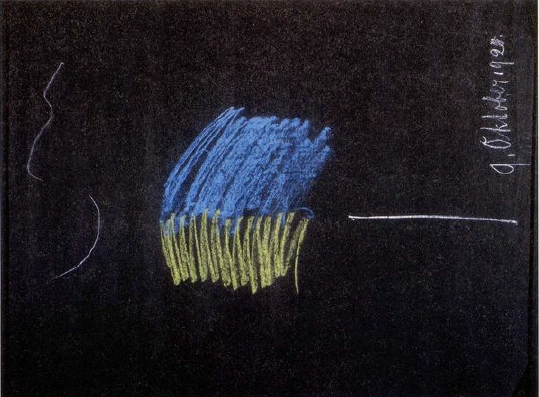

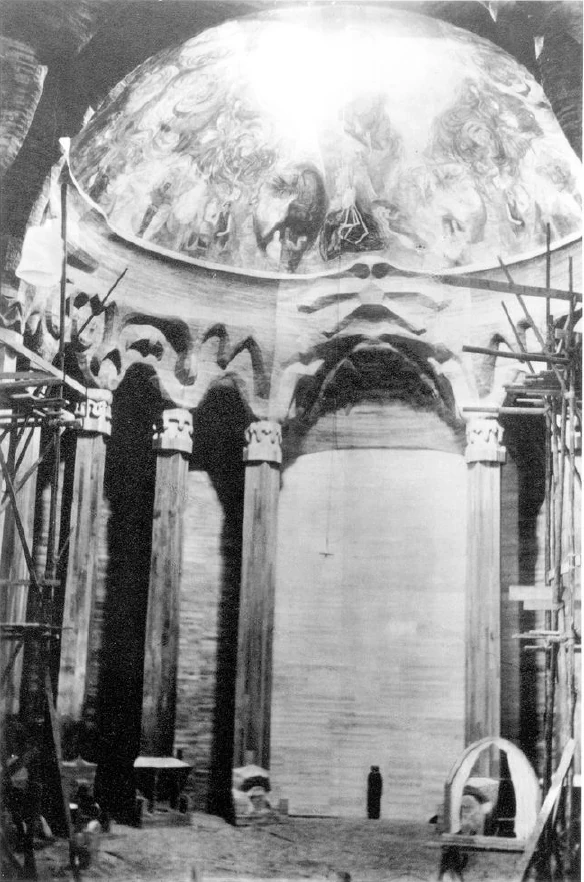

To take one detail, I would like to mention the small dome (Fig. 57). Later, at the end of this hour, we will raise the curtain and you can then take a look at the small dome. Above all, I would like this small dome to be understood in such a way that nothing abstract is fantasized into it. For in this small dome, in which I myself am essentially involved – this is of course not to say anything special about the also in turn initial and in many respects perhaps amateurish in the painting of this small dome – an attempt has been made to paint really out of color, out of the color experience. In fact, this color experience should be understood in such a way that one sees, above all, the color nuance at a particular point. It could not be a matter of, for example, at a certain point where, let us say, the blue was to be emphasized, where the blue was experienced according to its position near the opening, further away from the center, contrasting with the color effects in the center, of thinking of a fist (Fig. 70) and paint it there because one feels a kinship of the nature of the fist with the blue color, but it could only be a matter of developing the color experience of the blue at this point and then letting the form, the shape, the essence arise out of the color. It had to become what it is there out of necessity.

From this you can see that it is not important to the person who originally gave rise to the idea of forming a figure out of the color experience of blue at this point, which then leads the feeling back to the sixteenth century, reminiscent of the Faust figure, but rather that it is important to him to give birth to form and essence out of the living color. And if, in the end, interpretations are attributed to the works, then one must be aware that these are interpretations from the outside, that they may help one or another subjectivity to experience this or that; but I myself prefer it if you completely forget, when facing this small dome, that there is something Faustian, something Apollonian ( Fig. 76) or of any doppelgänger (Fig. 84) and the like, and that you first surrender to the pure color experience from which the whole is born, and that you are initially just as indifferent to whether there is a Faust crouching there or some other figure, just as the person who wanted to create from the color was indifferent to whether this figure emerged. It just came out because the world lives in color.

But one must not take the starting point from the linear or symbolic boundaries of the being; rather, one must take the starting point from painting from the color experience, from moving in color, so that the color and especially the color harmonization and disharmonization come to life as such. One will then see that one narrows one's view of the world if one tries to translate the intellectually abstract world view — even one that arises as spiritual science — simply symbolically, allegorically into color or into form. Rather, one will see that when one immerses oneself in color, the whole richness of the life of color overflows one and that in this immersion in the world of color one has, that one still discovers a new world. While with every allegory you only bring the world you already have into the colorful world, if you start from the colored experience itself, you discover a new world that is as creative in itself as the world you have in mind when you summarize the external natural fact in abstractions or in natural laws.

In this description – because everything artistic, when it is discussed, must be described – I had to show you how an attempt has been made here in this building, not to secretly incorporate anything into the plastic forms, into the color nuances, but to experience the secrets of these worlds ourselves, which give us the means to express them artistically. And when one experiences the secrets of these worlds, then one gradually frees oneself from all straw-like allegorizing and straw-like symbolizing. In painting, for example, one learns to overcome the line, even in the representation of the copperplate engraving or the woodcut, and to allow form to arise purely out of the contrast between light and dark. It is out of such experiences, not out of abstract thought, that the building idea of Dornach has come into being, out of what can be experienced in colour, in form, in surface, what can be felt as that which strives upwards, freeing itself from burdens, as that which works downwards, bearing burdens, bringing them to life within itself.

All this is here in architecture, sculpture, painting, even in the window panes - the nature of which I will also discuss next time - felt, experienced, not thought; because all abstract thinking is the death of art. The life of art is born only out of form, out of color, out of the burdened, out of the carrying, out of the rounded, out of the angular – I now mean “rounded” and “angular” as a verb. And when one can live in the round, in the angular, in the burden, in the carrying, in the arching, in the covering and opening, in the plastically rounding, in the surface giving, in the expressing the interior in the exterior through the special surface treatment, when one can experience what arises like beings in the waves from the surface of the sea, when one experiences from the living colors, then the forms are formed in such a way that they are a creation of the color. Then there is truly no allegorization, no symbolization; then, alongside that world of abstraction or the merely non-sensuous spiritual, a completely new world arises, a world that Goethe called the sensuous-suprasensible world. This world is not, however, killed by the merely intellectual, and it is brought to life when one knows how to set the spirit within oneself in motion, not by going so far in the contemplation of the external that the sensual contemplation leads to the linking of thoughts, but in such a way that one sees the supersensible directly in the external, in the sensual. When the inner life, which in Expressionism always seeks to give rise to thought, is restrained to such an extent that it does not reach thought, but remains in the mere experience of the formative, of that which permeates the surface with the intensity of color and when the world is experienced in this way, as it can only be experienced in the element of sensation, not in the element of thought, then this experience can truly provide the stimulus for a new art.

2. Die den Baugedanken Tragenden Künstlerischen Impulse

In diesem heutigen Vortrage wird es meine Aufgabe sein, einiges beizutragen zum Verständnis dessen, was in den künstlerischen Impulsen liegt, die den Baugedanken von Dornach tragen, um dann in dem nächsten dieser Vorträge diesen Baugedanken genauer auszuführen. Es wird schon nötig sein, dass ich gewissermaßen auch über diese künstlerischen Impulse einiges spreche aus dem Grunde, weil ja gerade über diese Impulse starke Missverständnisse sich verbreitet haben.

Es handelt sich ja darum - und das geht wohl schon hervor aus dem, was ich vor acht Tagen hier gesagt habe über das Herausentwickeln des Dornacher Baues aus unserer ganzen anthroposophischen Bewegung-, dass durch diesen Dornacher Bau in keiner Weise etwas geschaffen werden sollte, was ein Hineintragen abstrakter Geistigkeit in das eigentlich Künstlerische genannt werden müsste. Es sollte der Dornacher Bau durchaus aus künstlerischen Kräften selbst geschaffen werden. Und es sollte durch diesen Bau - wenigstens für eine Entwicklungsrichtung nach diesem Ziele hin - der Anfang gemacht werden, um das, was in der Geisteswissenschaft als Geistiges wirkt, auch ausfließen, ausströmen zu lassen in künstlerische Formen, in künstlerische Gestaltungen und so weiter. Das ist ja etwas, was geradezu erkämpft werden musste gegen gewisse Bestrebungen, die im entgegengesetzten Sinne sehr leicht gerade in einer solchen Bewegung laufen, wie es die anthroposophische ist.

In eine solche Bewegung kommen sehr leicht herein allerlei mystifizierende Elemente. die durch ein falsches Mystifizieren nach dem Abstrakten hin drängen, und die eigentlich - weil ja das Künstlerische in dem Gestalten und Bilden des Äußeren sich darleben muss — gerade an diesem Künstlerischen vorbeigehen und nach dem Symbolischen, nach dem Allegorischen hinstreben. Sie möchten gewissermaßen den Geist in seiner abstrakten Gestalt behalten, und in dem, was äußerlich gestaltet und gebildet wird, nur eine symbolische Veranschaulichung des Geistigen haben.

Mit so etwas erreicht man eine Ertötung, eine Lähmung alles wirklich Künstlerischen. Nach dieser Richtung hat man ja, durch das Hereindringen falscher Mystik aus der theosophischen in die anthroposophische Bewegung, alles Mögliche erleben müssen. Man hat erlebt, dass zum Beispiel eine Dichtung wie «Hamlet», die doch eine künstlerische Schöpfung ist, allegorisch mystisch ausgedeutet wurde, sodass die eine Gestalt aufgefasst wurde als das Geistselbst, die andere als der astralische Leib und so weiter. Ein Allegorisieren ohne Ende ist vielfach vorhanden unter denen, die sich zu einer solchen Geistesbewegung bekennen möchten, und ich habe zum Beispiel einmal Folgendes erleben müssen: Als ich versuchte, das bekannte Bild «Die Melancholie» von Dürer in der Weise zu besprechen, dass ich alles das, was in diesem Bilde lebt, zurückführte auf das Helldunkel und zeigte, wie es Dürer darauf ankam, in die Geheimnisse des Helldunkels einzudringen, das Finstere mit dem Hellen, die Finsternis mit dem Lichte wirklich in der mannigfaltigsten Weise zu kontrastieren, ertönte aus dem Zuhörerraum eine Stimme, die sagte: Ja, kann man denn dieses Bild nicht noch tiefer auffassen? Die tiefe Auffassung suchte man offenbar darin, dass man aus dem künstlerisch erfassten Helldunkel sich herausschälen wollte eine abstrakt-allegorische Ausdeutung desjenigen, was auf dem Bilde dargestellt ist, was Dürer schon dadurch verboten hat, dass er das Polyeder hineingestellt hat in das Bild, um anzudeuten, wie es ihm darauf ankomme, jene Helldunkel-Mannigfaltigkeit zum Ausdrucke zu bringen, die dann anschaulich wird, wenn man verschieden gerichtete Flächen, verschieden gestellte Flächen eines Polyeders oder die verschiedenen Flächenlagen einer Kugel gegenüberstellt irgendeinem sich ausbreitenden Lichte. Dass es unendlich viel tiefer ist, in dieses Wirken und Weben des Lichtes und der Dunkelheit hineinzuschauen und den eigenen Geist auszubreiten über dieses Weben von Hell und Dunkel, dass das für den, der künstlerisch empfindet, unendlich viel tiefer sein kann als die abstrakt-verstandesmäßige allegorische Ausdeutung solcher Bilder, dafür hatte ein solcher Zwischenrufer kein Verständnis.

Und so musste das, was in diesem Bau vorhanden ist als ein anfänglicher, schwacher Versuch, in vieler Beziehung gewissermaßen erkämpft werden gegen jene Bestrebungen, die nach dem Allegorisieren, nach dem Symbolisieren hingehen. Diese kann man ja genügend erleben, wenn man in einzelne besonders feierlich hergerichtete Lokale, in denen anthroposophische Geisteswissenschaft getrieben wird, kommt und sieht, dass man da versucht, mit Farben und mit allerlei Malereien und Zeichnungen allerhand zu beginnen, aber dass dieses Beginnen zuletzt doch zu nichts anderem führt, als dass jedes künstlerische Gefühl beleidigt wird durch das Malen eines scheußlichen Rosenkreuzes, bei dem es nur auf die Allegorie ankommt, in sieben in einer gewissen Weise an ein Kreuz hingemalten Rosen irgendeine Symbolik zu zeigen. Ich muss das erwähnen, damit, wenn anthroposophisch orientierte Geisteswissenschaft auch ihre künstlerische Fruchtbarkeit vor der Welt zeigen soll, man wisse, dass nicht verwechselt werden darf dasjenige, was künstlerisch versucht wird, mit all den Scheußlichkeiten, die aus dem Symbolisieren und Allegorisieren zuweilen gerade auf einem solchen mystischen Boden leicht erwachsen, auf den ich da hingedeutet habe.

Es handelt sich durchaus darum, dass gerade dem wahren Geisteswissenschafter durch unmittelbare Anschauung klar wird, worin das Wesen des Ideellen besteht, sodass er den Übergang finden kann von dem Ideellen zu dem, was sich in Prosaworten nun einmal aussprechen muss, trotzdem diese Prosaworte nur ein ungenügendes Offenbarungsmittel für die reiche Offenbarung der geistigen Welt selber sind, und dass sich ihm gegenüber dieser notwendigen Prosadarstellung - die aber auch gewisse Formen annehmen muss, wenn sie der geistigen Welt gerecht werden will - scharf abhebt die eigentliche künstlerische Darstellung, auch die der übersinnlichen Anschauung, die nichts von Symbolisieren oder Allegorisieren in sich hat.

Deshalb musste ich in dem Vortrage, den ich über Deklamation und Rezitation vor Ihnen zu halten hatte, darauf hinweisen, dass es ein Unfug ist, wenn man zum Beispiel in meine Mysteriendramen alles Mögliche, was eigentlich anthroposophische Theorie ist, nun in diese Mysteriendramen hineinphantasiert und hineinallegorisiert. Bei den Dramen handelt es sich durchaus darum, sie künstlerisch zu verstehen; und ich selber, wenn ich diese persönliche Bemerkung machen darf, erleide die unsäglichsten Schmerzen, wenn mir jemand abstrakte Begriffe entgegenbringt, die diese Mysteriendramen «erklären» sollen. Diese Mysteriendramen sind angeschaut, sind bis auf das einzelne Wort, bis auf den Tonfall so erlebt, wie sie dastehen, und derjenige; der da Allegorisierung hineinbringt, der versteht sie eben nicht der kann auch nicht dasjenige Maß von Übersinnlichkeit, das in ihnen liegt, wirklich herausholen — denn er prägt.nur die verstandesmäßigen Begriffe in das hinein, was eigentlich im künstlerischen Sinne erlebt werden sollte. Und so ist es mit allem Übrigen, was an Künstlerischem hervorgehen soll aus jenen Impulsen, aus denen die Geisteswissenschaft selber hervorgeht.

Ich möchte es einmal deutlich sagen, obzwar das etwas pedantisch klingen wird: Aus der Geisteswissenschaft selber, so wie sie in Worten mitgeteilt wird, kann natürlich keine Kunst hervorgehen; da kann nur Allegorisieren und Symbolisieren hervorgehen. Aber aus denjenigen geistigen Impulsen, die hinter der Geisteswissenschaft stehen, die diese Geisteswissenschaft selber wie einen Ast aus sich hervortreiben, aus denen geht dann hervor, als ein anderer Ast aus demselben Ursprung, auch ein künstlerisches Schaffen. Daher werden diejenigen, welche die Geisteswissenschaft abstrakt auffassen und sie dann in Kunst übersetzen wollen, niemals etwas anderes schaffen können als stroherne Allegorien oder leblose Symbole.

Man hat vielfach gesagt, in diesem Bau seien Symbole zu finden, Allegorien zu finden. Kein einziges Symbol, keine einzige Allegorie wird man, wenn man den Bau richtig anschaut, in ihm entdecken können, sondern alles soll so sein — gewiss ist manches in anfänglichen Versuchen stehen geblieben -, dass es in die Form, in die Gestaltung, in die Farbe ausgeflossen ist. Und daher, weil so leicht Missverständnisse nach dieser Richtung sich bilden, möchte ich mich über einiges Künstlerische heute mit Ihnen verständigen, um, wie gesagt, zum eigentlichen Baugedanken dann das nächste Mal zu kommen und diesen ganz konkret zu charakterisieren.

Ich möchte davon ausgehen, dass, als wir einmal drüben in der Schreinerei aufzuführen hatten jene Szene aus dem zweiten Teil des Goethe’schen «Faust», in welchem die Kabiren vorkommen, ich versuchte, die drei Kabiren plastisch nachzuschaffen aus der übersinnlichen Anschauung, die sich ergibt, wenn man eben versucht, in die Mysterien von Samothrake einzudringen. Ich versuchte also plastisch diese Kabiren darzustellen, um sie auf die Bühne bringen zu können, nun waren diese drei Kabiren plastisch da. Dann entstand bei einer unserer Bewegung ganz nahestehenden Persönlichkeit der Wunsch, von diesen Kabiren auch einigen anderen Leuten eine Vorstellung zu geben, die sie nicht hier sehen können, oder die ein Andenken haben wollen an die Art und Weise, wie hier die Kabiren plastisch rekonstruiert sind, und da stand man vor der Frage, ob diese Kabiren-Plastiken nun fotografiert werden sollen.

Für den [aber], der plastisch-künstlerisches Gefühl hat, ist jede Fotografie einer Plastik eine Ertötung des eigentlichen plastischen Kunstwerkes. Und so entschloss ich mich dazu, einfach nun in einer Zeichnung, in Helldunkel, also in anderer Technik, diese Kabiren wiederzugeben. Da waren sie also auf der Fläche von vornherein flächenhaft künstlerisch gedacht, da konnte man sie fotografieren, das konnte man durch Fotografie verbreiten. Sie sehen also: Steht man wirklich auf dem Boden jener Lebekräfte, die in der Geisteswissenschaft pulsieren, dann eignet man sich vor allen Dingen ein wirklich künstlerisches Gefühl für die künstlerischen Mittel an, deren man sich bedient, und man eignet sich gefühlsmäßig, nicht verstandesmäßig, dasjenige an, was im Dasein lebt.

Ich will als Beispiel Folgendes erwähnen, was uns schon mehr in die Intimitäten des künstlerischen Nachfühlens des Weltenprozesses hineinführt, das wir dann zu gestalten versuchen. Nehmen wir an, man wollte so eine Art Menschheitsrepräsentanten plastisch hinstellen, wie ich es in meiner plastischen Gruppe versuchte, wo eine Christus-ähnliche Figur vorhanden ist (Abb. 94-98). Da würde man, wenn man diesen Menschheitsrepräsentanten plastisch hinstellen will, im plastischen Schaffen einfach dazu geführt werden, ganz anders zu fühlen gegenüber dem, was in der Kopfbildung vorhanden ist, als gegenüber dem, was in der übrigen Gestaltung des Menschen vorhanden ist, die außerhalb des Kopfes lebt.

Im plastischen Gestalten erfühlt man dasjenige, was an dem Menschen als ein gewaltiger Unterschied auftritt. Man fühlt da in diesem plastischen Gestalten, wo man es zu tun hat mit dem Formen von Flächen, dass im Haupte eine Gestaltung wirken muss, die gewissermaßen nach innen drängt, die abzieht von dem Äußeren, die aber von innen heraus gestaltet; und man fühlt, dass an dem übrigen Menschen einem dasjenige entgegentritt, was gerade im entgegengesetzten Sinne gestaltet. Es kommt gar nicht so sehr darauf an, dass man sagt, das eine geschieht von innen, das andere von außen - das würde schon wieder hinführen zu einer abstrakten, verstandesmäßigen Beschreibung -, sondern es kommt darauf an, dass man die entgegengesetzten Gefühle hat, wenn man aus den Tiefen des Weltprozesses heraus irgendeine Form entwickelt, die sich nur von innen nach außen gestalten lässt, oder wenn man herausnimmt eine Form, die sich nur von außen nach innen gestalten lässt, der man es gewissermaßen ansieht, wie die äußeren Weltenkräfte sich konzentrieren und von außen nach innen gestalten.

Wenn man nun in diesem Empfinden und Fühlen weitergeht, dann kommt man dazu, einzusehen, wie man — dadurch, dass man als plastischer Künstler dem Haupte gegenüber andere Empfindungen hat als dem übrigen Organismus gegenüber - etwas erlebt, was weder Schwerkraft, noch vertikal wirkende Auftriebskraft, noch auch ausgebreitete Kraft ist. Die reine ausgebreitete Kraft ist die, die wir im Lichte empfinden. Die reine Schwerkraft ist jene, die wir an unserem eigenen Gewichte empfinden und die wir namentlich erleben im Altern des Menschen, wenn man auf dieses Altern einen Blick wirklicher Selbstschau werfen kann. Von diesen beiden Kräften, Schwerkraft und Auftriebskraft, verspürt man eine Art Zusammenwirken so, dass, ich möchte sagen, die Auftriebskräfte, diejenigen Kräfte, die das Plastische vom Irdischen losreißen, sich mehr erfühlen lassen im Haupte, und diejenigen Kräfte, welche von der Erdenschwere heraufwirken und gewissermaßen den Leib herauftreiben, die fühlt man mehr bei der Gestaltung, bei der plastischen Herausbildung des übrigen Leibes.

Aber, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, wenn man das dann wirklich erfühlt hat, und — namentlich wenn man dieses Gefühl metamorphosiert hat in künstlerisches Schaffen — wenn man wirklich nicht in einer abstrakten Vorstellung, sondern in diesem Erfühlen lebt und sich bemüht, in den Stoff dasjenige hineinzubringen, was man da fühlt, dann empfindet man eben einen starken Unterschied ... [Lücke im Stenogramm]. Zum Beispiel ist in der Plastik etwas zu erfühlen wie ein Ausgleich von zwei Kräften, von denen der Plastiker selbst gar nichts zu wissen braucht. Selbst derjenige, der etwas weiß von solchen Kräften wie ausgebreitete Kraft, Schwerkraft und Auftriebskraft, vergisst es vollständig im plastischen Schaffen; da geht es ihn nichts an, da lebt er rein im Erfühlen der Ausdehnung der Kräfte der Fläche, im Erfühlen desjenigen, wie die Fläche sich im Raume ausdehnt, oder in der Gestaltung der Fläche selber. Hat man sich nichts abstrakt Begriffliches angeeignet - das heißt, kann man den Rock des Ideellen vollständig ausziehen, wenn man sich in das künstlerische Schaffen hineinlebt -, dann wird man in gewisser Weise, indem man sich hineinlebt in das künstlerische Schaffen, ein anderer seelischer Mensch; dann eignet man sich auch ein Gefühl an für die Verschiedenheit der künstlerischen Ausdrucksmittel.

Und wenn man übergeht vom Wirken an der Plastik zum Wirken in der Malerei, dann kommt man dazu, sich zu sagen: All das, was man gegenüber der Plastik sagen muss von der Art des Zusammenwirkens von in vertikaler und in Ausbreitungsrichtung wirkenden Kräften, von Schwereelement und Lichtelement, all das muss man wieder abgelegt haben, wenn man es in der Malerei mit der Farbe und ihren Nuancierungen zu tun hat. Denn da handelt es sich darum, nicht aus der Linie, nicht aus der Form, sondern aus der Farbe heraus zu schaffen, sodass man da völlig aufhört, wie der Plastiker dem Haupte gegenüber anders zu fühlen als gegenüber dem übrigen Organismus. In der Malerei fühlt man jenen Unterschied verschwinden, der sich dem Plastiker ergeben hat zwischen dem Haupte und dem, was nicht Haupt ist am Menschen. Es gleicht sich das vollständig aus und wird zu etwas ganz anderem, zu einem innerlich Intensiven, das gar nicht dargestellt werden kann durch einen Gegensatz der Linien, sondern nur dargestellt werden kann durch ein Hineindringen in das Intensive der Farbennuancierung, sodass da gar nicht eingegangen werden kann zum Beispiel auf dasjenige, was in der Plastik noch sehr stark hervortritt.

Und will man es überwinden, so kann man es nur dann überwinden, wenn man die Plastik doch in einem gewissen Grade bis zur Bewusstheit treibt, wie es in meiner Mittelpunktsgruppe für diesen Bau geschehen ist. Aber geht man in die Malerei hinüber, so handelt es sich darum, dass man gründlich ablehne irgendein Denken in Linien und dass man übergeht zu dem Gefühl, das rein aus der Farbe heraus schafft. Und so sonderbar es dem erscheinen wird, der in einem falsch abstrakten Sinn von einer Vergeistigung der Kunst redet, so muss doch gesagt werden: Für den, der malerisch denkt, handelt es sich vor allen Dingen darum, dass an einer bestimmten Stelle einer bestimmten Fläche irgendeine Farbennuance ist und dass, wenn man von dieser Farbennuance zu einer anderen Stelle der Fläche übergeht, andere Farbennuancen da sind. Um das Schaffen aus der Farbe heraus handelt es sich.

Der Künstler wird allerdings in diesem Schaffen unterstützt durch das, was ich das Erlebnis an der Farbe nennen möchte, das Erlebnis an dem Blau, das Erlebnis an dem Gelb, das Erlebnis an dem Rot. Was der Künstler hat, indem er das Gelb, das Rot so erlebt, als ob es ihn attackiere, das Blau so erlebt, als ob er ihm nachlaufen müsste mit seiner Seele, als ob er sich selber hinausweiten müsste, das ist das, was sich in ihm umwandelt zum Schaffen, und was ihm dann eben die Möglichkeit gibt, die Empfindung umzugestalten in das, was Kunstwerk werden soll. Wenn man zum Beispiel vor der Aufgabe steht, irgendeine Fläche auszumalen, so wird es sich ja darum handeln, dass man zu nuancieren hat zwischen sogenannten hellen, warmen Farben und dunklen, kalten Farben. Hat man das Farbenerlebnis, kann man aus diesem Farbenerlebnis heraus schaffen, wie der Musiker aus dem Tonerlebnis heraus schafft, dann handelt es sich darum, dass aus der Farbe selbst heraus die Form entsteht, sodass man nicht zeichnet und dann in die Linienräume, die durch das Zeichnen entstehen, die Farbe hereinschmiert, sondern darum handelt es sich, dass man schon ursprünglich von dem Farbenerlebnis ausgeht und dass sich einem aus dem Farbenerlebnis heraus das Linien erlebnis, die Form erst ergibt. Deshalb sagte ich in dem ersten meiner Mysteriendramen an einer Stelle - das heißt, ich ließ eine Persönlichkeit sagen, der ich das in den Mund legte -, dass die Form «der Farbe Werk» sein müsse.

Im Grunde genommen - man muss sich dessen bewusst sein - ist alles Zeichnen und alles Denken im Zeichnen gegenüber der Malerei eigentlich verlogen. Denn sehe ich zum Beispiel den blauen Himmel, darunter das Meeresgrün der Fläche des Meeres, so habe ich oben das Blau des Himmels, unten das Grün des Meeres, und die Linie des Horizontes entsteht einfach aus dem Sehen, aus dem Farbenerlebnis. Und ich lüge eigentlich, wenn ich eine Horizontlinie hinzeichne, die eigentlich gar nicht da ist (Abb. 114). Das muss nun wirklich einmal in gründlicher Weise angeschaut werden, sonst kommt man nämlich nicht hinein in jene Welt, die erlebt werden kann an allen künstlerischen Ausdrucksmitteln, an den Farben und ihren Nuancierungen, ebenso wie an den Begriffen und Ideen, wenn diese Begriffe und Ideen wirklich drinnenstehen im Geistigen und nicht herausabstrahiert sind aus dem gewöhnlichen menschlichen Bewusstsein.

Sie sehen, hier kommt es weniger darauf an, etwa Geisteswissenschaft in allerlei Formen zum Ausdrucke zu bringen, sondern hier kommt es darauf an, für das künstlerische Anschauen Impulse zu gewinnen, die im Entwicklungsgang der Menschheit ebenso gefordert werden wie die Geisteswissenschaft selber. Aber sie werden als etwas Besonderes gefordert. Es ist so, dass einerseits die geisteswissenschaftliche Strömung geht und dass daneben die künstlerische Strömung geht, die in einer gewissen Weise nun auch ihrerseits neue Formen annehmen muss. Daher sage ich jedem, der vor jene Gruppe tritt, die hier Mittelpunktsgruppe werden soll: Man kann an der mittleren Figur so etwas empfinden wie die Christus-Gestalt, aber es muss empfunden werden, es darf nicht gedacht werden, dass der Christus-Name dort steht. Er wird äußerlich schon ganz gewiss nicht darauf stehen, aber er braucht nicht einmal gedacht zu werden, sondern es muss nur jenes Empfindungserlebnis ablaufen in uns, welches uns aufmerksam macht, wie wir die Sache so anschauen müssen, dass wir die Verehrung entwickeln, dass wir die Hochschätzung entwickeln, dass wir die Empfindung von den Tiefen des Menschenwesens entwickeln. Also lauter Empfinden, lauter Erleben in Empfindungen soll da sein, dieselben Empfindungen, die wir etwa erleben, wenn wir uns geistgemäß vertiefen in die Christus-Gestalt. Aber all das, was wir geistgemäß erleben, wenn wir uns durch Geisteswissenschaft selbst in die Christus-Gestalt vertiefen, darf nicht herübergetragen werden in dasjenige, was plastisch oder malerisch gestaltet wird. Was plastisch oder malerisch gestaltet wird, das ist aus der Form, aus der Linie, aus der Fläche heraus zu gebären. Und dieses Leben in der Form, in der Linie, in der Fläche, in der Farbe, im Worte selbst, das ist es, was im Weiteren solche Formen ausbildet, solch eine Malerei ergibt, wie sie hier in diesem Bau vor Sie hintreten sollen.

Was ich jetzt gesagt habe, hat nicht viel zu tun mit dem Bau als solchem, sondern nur mit der künstlerischen Gesinnung und künstlerischen Empfindung, die dem ganzen Baugedanken von Dornach zugrunde liegt, wobei man immer berücksichtigen muss, dass er im Anfange der Entwicklung jenes Baustiles, jener künstlerischen Formensprache steht, von der man sich erst versprechen kann, dass sie in der Zukunft in besonderer Weise gedeihe. Denn ein zweites Mal würde ich diesen Bau nicht wiederum in derselben Weise aufführen. Nicht deshalb, weil ich die ihm zugrunde liegende künstlerische Gesinnung etwa für verfehlt halte — das ist nicht der Fall -, sondern weil alles das, was lebendig ist, sich eben auch fortgestaltet, weil ein zweites Mal alle jene Fehler vermieden würden und alles, was man in Bezug auf Vervollkommnungsimpulse sagt, beachtet werden könnte. Aber all das sehe ich selber und nehme es viel genauer als gerade jene, die sich oftmals Kritiker des Baues nennen. Ich kenne heute die Fehler sehr gut und weiß, was man vermeiden könnte, wenn man den Bau noch einmal aufführen würde, und was in ihn hineinzubringen wäre, wenn er noch einmal aufgeführt würde. Und notwendig ist es, dass alle Einzelheiten des Baugedankens von Dornach so aufgefasst werden.

Um von einer Einzelheit auszugehen, möchte ich die kleine Kuppel (Abb. 57) erwähnen. Später, am Ende dieser Stunde, werden wir den Vorhang aufmachen, und Sie können dann sich die kleine Kuppel etwas anschauen. Ich möchte vor allen Dingen diese kleine Kuppel so aufgefasst wissen, dass ganz und gar nichts Abstraktes in sie hineinphantasiert werde. Denn in dieser kleinen Kuppel, an der ich selbst wesentlich beteiligt bin — damit ist natürlich nicht etwas Besonderes gesagt über das auch wiederum Anfängliche und in vieler Beziehung vielleicht dilettantisch zu Nennende in der Malerei dieser kleinen Kuppel -, ist einmal versucht worden, nun wirklich aus der Farbe, aus dem Farbenerlebnis heraus zu malen. Tatsächlich soll dieses Farbenerlebnis so aufgefasst werden, dass man vor allen Dingen die Farbennuance an einer bestimmten Stelle sieht. Es konnte sich nicht darum handeln, dass zum Beispiel an einer bestimmten Stelle, wo besonders, sagen wir, durch das Blau gewirkt werden sollte, wo das Blau erlebt worden ist nach seiner Lage nahe der Öffnung, weiter weg von der Mitte, kontrastierend mit den Farbenwirkungen in der Mitte, da etwa einen Faust (Abb. 70) auszudenken und ihn dorthin zu malen, weil man eine Verwandtschaft des Faustwesens mit der blauen Farbe empfindet, sondern es konnte sich nur darum handeln, das Farbenerlebnis des Blaus an dieser Stelle zu entwickeln und dann die Form, die Gestalt, die Wesenheit aus der Farbe heraus entstehen zu lassen. Die musste mit Notwendigkeit so werden, wie sie da ist.

Daraus ersehen Sie, dass es dem, der ursprünglich die Veranlassung gegeben hat, hier an dieser Stelle aus dem Farbenerlebnis des Blaus heraus gerade eine Gestalt zu formen, die dann das Empfinden zurückführt ins sechzehnte Jahrhundert, die erinnert an die Faustgestalt, nicht darauf ankommt, die Faustgestalt an diese Stelle hinzusetzen, sondern dass es ihm darauf ankommt, aus der lebendigen Farbe heraus Form und Wesenheit gebären zu lassen. Und wenn zuletzt irgendwelche Interpretationen in die Dinge hineingetragen werden, so muss man sich bewusst sein, dass das von außen hineingetragene Interpretationen sind, dass sie ja helfen können der einen oder der anderen Subjektivität, dies oder jenes zu erleben; aber mir selbst ist es am allerliebsten, wenn Sie dieser kleinen Kuppel gegenüber ganz vergessen, dass da irgendetwas von einem Faustischen, von einem Apollohaften (Abb. 76) oder von irgendeinem Doppelgänger (Abb. 84) und dergleichen ist, und sich zunächst dem reinen Farbenerlebnis, aus dem das Ganze herausgeboren ist, hingeben und es Ihnen zunächst ebenso gleichgültig ist, ob da ein Faust hockt oder irgendein anderer, so wie es demjenigen, der aus der Farbe heraus schaffen wollte, selber gleichgültig war, dass diese Figur herauskam. Sie kam eben heraus, weil in der Farbe die Welt lebt.

Den Ausgangspunkt muss man aber nicht nehmen von der linienhaften oder symbolischen Begrenzung des Wesens, sondern den Ausgangspunkt muss man bei der Malerei nehmen von dem Farbenerlebnis, von dem Sich-Bewegen in der Farbe, damit die Farbe und namentlich die Farbenharmonisierung und - disharmonisierung als solche lebendig werden. Man wird dann sehen, dass man sich die Welt verengt, wenn man das verstandesmäßig Abstrakte der Weltanschauung — auch derjenigen, die sich als Geisteswissenschaft ergibt - versucht, einfach symbolisch, allegorisch ins Farbige umzusetzen oder ins Formenhafte. Man wird vielmehr sehen, dass, wenn man in die Farbe sich hineinlebt, der ganze Reichtum des Farbenlebens einen überströmt und dass man in diesem Hineinleben in die Farbenwelt eben das hat, dass man noch eine neue Welt entdeckt. Während man mit jedem Allegorisieren nur die Welt, die man schon hat, hineinträgt auch in das Farbige, entdeckt man, wenn man vom farbigen Erlebnis selber ausgeht, eine neue Welt, die aus sich heraus so schöpferisch ist wie diejenige Welt, die man im Sinne hat, wenn man die äußere Naturtatsache in Abstraktionen ‚oder in Naturgesetzen zusammenfasst.

Ich musste Ihnen in dieser Umschreibung - denn alles Künstlerische, wenn es besprochen wird, muss ja umschrieben werden -, ich musste Ihnen in dieser Umschreibung zeigen, wie hier in diesem Bau versucht worden ist, nicht irgendetwas in die plastischen Formen, in die Farbennuancierungen hineinzugeheimnissen, sondern wie versucht worden ist, die Geheimnisse dieser Welten, die uns die Mittel geben zum künstlerischen Darstellen, selbst zu erleben. Und wenn man die Geheimnisse dieser Welten erlebt, dann kommt man erst allmählich ab von all dem strohernen Allegorisieren, von all dem strohernen Symbolisieren. Man lernt zum Beispiel in der Malerei die Linie zu überwinden, ja selbst noch bei der Darstellung des Kupferstiches oder des Holzschnittes die Linie zu überwinden und lediglich aus der Kontrastierung des Hell-Dunkels heraus die Form entstehen zu lassen. Aus einem solchen Erleben, nicht aus einem abstrakten Gedanken heraus, ist zusammengeflossen der Baugedanke von Dornach, aus dem, was an Farbe, an Formen, an Flächen erlebt werden kann, was empfunden werden kann als das Hinaufstrebende, sich von den Lasten Befreiende, als das Hinunterwirkende, das Lastende in sich zum Leben Bringende.

All das ist hier in Architektur, Plastik, Malerei, bis in die Fensterscheiben hinein - von deren Wesen ich auch das nächste Mal werde zu sprechen haben -, bis in diese Fensterscheiben hinein empfunden, erlebt, nicht gedacht; denn jedes abstrakte Denken ist der Tod der Kunst. Das Leben der Kunst wird allein herausgeboren aus Form, aus Farbe, aus dem Lasten, aus dem Tragen, aus dem Runden, aus dem Eckigen - ich meine jetzt «Runden» und «Eckigen» als Verbum. Und wenn man so leben kann in dem Runden, in dem Eckigen, in dem Lasten, in dem Tragen, in dem Sich-Wölben, in dem Zudeckenden und Sich-Öffnenden, in dem sich plastisch Rundenden, in dem Flächengebenden, in dem das Innere im Äußeren durch die besondere Flächengebung Ausdrückenden, wenn man erleben kann dasjenige, was heraufsteigt wie Wesen in den Wellen aus der Meeresfläche, wenn man aus den lebendigen Farben erlebt, dann bilden sich die Formen so, dass sie Schöpfung der Farbe sind. Dann entsteht wahrhaftig nicht Allegorisierung, nicht Symbolisierung, dann entsteht neben jener Welt der Abstraktion oder des bloß unsinnlichen Geistigen eine ganz neue Welt, eine Welt, die Goethe die sinnlich-übersinnliche Welt nannte. Diese Welt wird aber ertötet von dem bloß Gedanklichen, und sie wird belebt, wenn man den Geist in sich in Tätigkeit zu versetzen weiß, indem man im Anschauen des Äußeren nicht so weit geht, dass das sinnliche Anschauen zu Gedankenverknüpfungen führt, sondern so, dass man das Übersinnliche unmittelbar in dem Äußeren, dem Sinnlichen sieht. Wenn das Innere, das sich im Expressionismus immer heraufbilden will zum Gedanken, so gezügelt wird, dass es nicht bis zum Gedanken kommt, sondern wenn es stehen bleibt im bloßen Erleben des Formenden, des die Fläche mit der Intensität der Farbe Durchdringenden, und wenn die Welt so erlebt wird, wie sie nur erlebt werden kann im Elemente der Empfindung, nicht im Elemente des Gedankens, dann kann aus diesem Erleben heraus wirklich die Anregung gegeben werden zu einer neuen Kunst.