| 214. Esoteric Development: Attainment of Supersensible Knowledge

20 Aug 1922, Oxford Translated by Gertrude Teutsch, Olin D. Wannamaker, Diane Tatum, Alice Wuslin Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| 214. Esoteric Development: Attainment of Supersensible Knowledge

20 Aug 1922, Oxford Translated by Gertrude Teutsch, Olin D. Wannamaker, Diane Tatum, Alice Wuslin Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

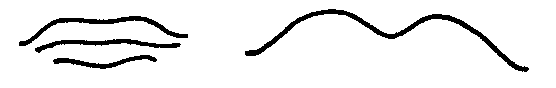

Translator Unknown, revised I should like to respond to the kind invitation to lecture this evening by telling you how, by means of direct investigation, it is possible to acquire the spiritual knowledge which we are proposing to study here in its application to education. I shall be dealing today with the methods whereby super-sensible worlds may be investigated and on another occasion it may be possible to deal with some of the actual results of super-sensible research. But apart from this, let me add by way of introduction that everything I propose to say will refer to the investigation of spiritual worlds, not to the understanding of the facts yielded by super-sensible knowledge. These facts have been investigated and communicated, and they can be grasped by healthy human intelligence, if this healthy intelligence will be unprejudiced enough not to base its conclusions wholly on what goes by the name of proof, logical deduction, and the like, in regard to the outer sense world. On account of these hindrances it is frequently stated that unless one is able oneself to investigate super-sensible worlds, one cannot understand the results of super-sensible research. We are dealing here with what may be called initiation-knowledge—that knowledge which in ancient periods of human evolution was cultivated in a somewhat different form from that which must be fostered in our present age. Our aim, as I have already said in other lectures, is to set out along the path of research leading to super-sensible worlds by means of the thinking and perception proper to our own epoch—not to revive what is old. And precisely in initiation-knowledge, everything depends upon one being able to bring about a fundamental reorientation of the whole human life of soul. Those who have acquired initiation-knowledge differ from those who have knowledge in the modern sense of the word, and not only by reason of the fact that initiation-knowledge is a higher stage of ordinary knowledge. It is, of course, acquired on the basis of ordinary knowledge, and this basis must be there. Intellectual thinking must be fully developed if one wishes to reach initiation-knowledge. But then a fundamental reorientation is necessary; for he who possesses initiation-knowledge must look at the world from an entirely different point of view from one without initiation-knowledge. I can express in a simple formula how initiation-knowledge principally differs from ordinary knowledge. In ordinary knowledge, we are conscious of our thinking, and of all those inner experiences whereby we acquire knowledge, as the subjects of this knowledge. We think, for example, and we believe that we are understanding something through our thoughts. When we conceive of ourselves as thinking beings, we are the subject. We seek for objects, in that we observe nature and human life, and in that we make experiments. We seek always for objects. Objects must press against us. Objects must yield themselves to us so that we may grasp them with our thoughts and apply our thinking to them. We are the subject; that which comes to us is the object. An entirely different orientation is brought about in a man who is reaching out for initiation-knowledge. He has to realize that, as man, he is the object, and he must seek for the subject to this human object. Therefore the complete reverse must begin. In ordinary knowledge we feel ourselves to be the subject and we seek the objects that are outside us. In initiation-knowledge we ourselves are the object and we seek for the subject—or rather in actual initiation-knowledge the subject appears of itself. But that is then a matter of a later stage of knowledge. So you see, even this rather theoretical definition indicates that in initiation-knowledge we must really take flight from ourselves, that we must become like the plants, the stones, the lightning and thunder which, to us, are objects. In initiation-knowledge we slip out of ourselves, as it were, and become the object which seeks for its subject. If I may use a somewhat paradoxical expression—in this particular connection in reference to thinking—in ordinary knowledge we think about things; in initiation-knowledge we must discover how our being is “thought” in the cosmos. These are nothing but abstract principles, but these abstract principles you will now find pursued everywhere in the concrete data of the initiation method. Now firstly—for today we are dealing only with the form of initiation-knowledge that is right and proper for the modern age—initiation-knowledge takes its start from thinking. The life of thought must be fully developed if one wishes to attain initiation-knowledge today. And a good training for this life of thought is to give deep study to the growth and development of natural science in recent centuries, especially in the nineteenth century. Human beings proceed in different ways when they embark upon the quest for scientific knowledge. Some of them absorb the teachings of science with a kind of naiveté, hearing how organic beings are supposed to have evolved from the simplest, most primitive forms, up to man. They formulate ideas about this evolution but pay little heed to their own being, to the fact that they themselves have ideas and in their very perception of outer processes are themselves unfolding a life of thought. But there are some who cannot accept the whole body of scientific knowledge without turning a critical eye upon themselves, and they will certainly come to the point of asking: “What am I myself really doing when I follow the progress of beings from the imperfect to the perfect stage?” Or again, they must ask themselves: “When I am working at mathematics I evolve thoughts purely out of myself. Mathematics in the real sense is a web which I spin out of my own being. I then bring this web to bear upon things in the outer world and it fits them.” Here we come to what I must say is the great and tragic question that faces the thinker: “How do matters stand regarding thinking itself—this thinking that I apply with all knowledge?” Not for all our contemplation shall we discover how matters really stand regarding thought itself, for the simple reason that thinking there remains at the same level. All that we do is to revolve around the axle which we have already formed for ourselves. We must perform something with thinking, by means of what I have described as meditation in my book, Knowledge of the Higher Worlds and its Attainment. One should not have any “mystical” ideas in connection with meditation, nor indeed imagine that it is an easy thing. Meditation must be something completely clear, in the modern sense. Patience and inner energy of soul are necessary for it, and, above all, it is connected with an act that no man can do for another, namely, to make an inner resolve and then hold to it. When he begins to meditate, man is performing the only completely free act there is in human life. Within us we have always the tendency to freedom and we have, moreover, achieved a large measure of freedom. But if we think about it, we shall find that we are dependent for one upon heredity, for another upon education, and for a third upon our life. And ask yourself where we would be if we were suddenly to abandon everything that has been given us by heredity, education, and life in general. If we abandoned all this suddenly, we would be faced with a void. But suppose we undertake to meditate regularly, in the morning and evening, in order to learn by degrees to look into the super-sensible world. That is something which we can, if we like, leave undone any day; nothing would prevent that. And, as a matter of fact, experience teaches that the greater number of those who enter upon the life of meditation with splendid resolutions abandon it again very soon. We have complete freedom in this, for meditation is in its very essence a free act. But if we can remain true to ourselves, if we make an inner promise—not to another, but to ourselves—to remain steadfast in our resolve to meditate, then this in itself will become a mighty force in the soul. Having said this, I want to speak of meditation in its simplest forms. Today I can deal only with principles. We must place at the center of our consciousness an idea or combination of ideas. The particular content of the idea or ideas is not the point, but in any case, it must be something that does not represent any actual reminiscences or memories. That is why it is well not to take the substance of a meditation from our own store of memories but to let another, one who is experienced in such things, give the meditation. Not, of course, because he has any desire to exercise “suggestion,” but because in this way we may be sure that the substance of the meditation is something entirely new for us. It is equally good to take some ancient work which we know we have never read before, and seek in it some passage for meditation. The point is that we not draw the passage from the subconscious or unconscious realms of our own being which are so apt to influence us. We cannot be sure about anything from these realms because it will be colored by all kinds of remains from our past life of perception and feeling. The substance of a meditation must be as clear and pure as a mathematical formula. We will take this sentence as a simple example: “Wisdom lives in the light.” At the outset, one cannot set about testing the truth of this. It is a picture. But we are not to concern ourselves with the intellectual content of the words—we must contemplate them inwardly, in the soul, we must repose in them with our consciousness. At the beginning, we shall be able to bring to this content only a short period of repose, but the time will become longer and longer. What is the next stage? We must gather together the whole human life of soul in order to concentrate all the forces of thinking and perception within us upon the content of the meditation. Just as the muscles of the arm grow strong if we use them for work, so are the forces of the soul strengthened by being constantly directed to the same content, which should be the subject of meditation for many months, perhaps even years. The forces of the soul must be strengthened and invigorated before real investigation in the super-sensible world can be undertaken. If one continues to practice in this way, there comes a day, I would like to call it the great day, when one makes a certain observation. One observes an activity of soul that is entirely independent of the body. One realizes too that whereas one's thinking and sentient life were formerly dependent on the body—thinking on the nerve-sense system, feelings on the circulatory system, and so on—one is now involved in an activity of soul and spirit that is absolutely free from any bodily influence. And gradually one notices that one can make something vibrate in the head—something which remained before totally unconscious. One now makes the remarkable discovery of where the difference lies between the sleeping and waking states. This difference lies in the fact that when one is awake, something vibrates in the whole human organism, with the single exception of the head. That which is in movement in the other parts of the organism is at rest in the head. You will understand this better if I call your attention to the fact that as human beings we are not, as we are accustomed to think, made up merely of this robust, solid body. We are really made up of approximately ninety per cent fluid, and the proportion of solid constituents immersed and swimming in these fluids is only about ten per cent. Nothing absolutely definite can be said about the amount of solid constituents in man. We are composed of approximately ninety per cent water—if I may call it that—and through a certain portion of this water pulsates air and warmth. If you thus picture man as being to a lesser extent solid body and to a greater extent water, air, and the vibrating warmth, you will not find it so very unlikely that there is something still finer within him—something which I will now call the etheric body. This etheric body is finer than the air—so fine and ethereal indeed that it permeates our being without our knowing anything of it in ordinary life. It is this etheric body which in man's waking life is full of inner movement, of regulated movement in the whole of the human organism, with the exception of the head. The etheric body in the head is inwardly at rest. In sleep it is different. Sleep commences and then continues in such a way that the etheric body begins to be in movement also in the head. In sleep, then, the whole of our being—the head as well as the other parts of the organism—is permeated by an inwardly moving etheric body. And when we dream, perhaps just before waking, we become aware of the last movements in the etheric body. They present themselves to us as dreams. When we wake up in a natural way we are still aware of these last movements of the etheric body in the head. But, of course, when there is a very sudden waking, it cannot be so. One who continues for a long time in the method of meditation which I have indicated is gradually able to form pictures in the tranquil etheric body of the head. In the book, Knowledge of the Higher Worlds and Its Attainment, I have called these pictures Imaginations. And these Imaginations, which are experienced in the etheric body independently of the physical body, are the first super-sensible impressions that we can have. They enable us, apart altogether from our physical body, to behold, as in a picture, the actions and course of our life back to the time of birth. A phenomenon that has often been described by people who have been at the point of drowning, namely that they see their life backwards in a series of moving pictures, can be deliberately and systematically cultivated so that one can see all the events of the present earthly life. The first thing that initiation-knowledge gives is the view of one's own life of soul, and it proves to be altogether different from what one generally supposes. One usually supposes in the abstract that this life of soul is something woven of ideas. If one discovers it in its true form, one finds that it is something creative, that it is that which, at the same time, was working in our childhood, forming and molding the brain, and is permeating our whole organism and producing in it a plastic, form-building activity, kindling each day our waking consciousness and even our digestive processes. We see this inwardly active principle in the organism of man as the etheric body. It is not a spatial body but a time-body. Therefore you cannot describe the etheric body as a form in space if you realize your doing so would be the same thing as painting a flash of lightning. If you paint lightning, you are, of course, painting an instant—you are holding an instant fast. The same principle applies to the etheric body of man. In truth, we have a physical space-body and a time-body, an etheric body which is always in motion. We cannot speak intelligently of the etheric body until we have discovered in actual experience that it is a time-body which comes before us in an instant as a continuous tableau of events stretching back to birth. This is what we can first discover in the way of the super-sensible abilities in ourselves. The effect of these inner processes upon the evolution of the soul, which I have described, manifests itself above all in the complete change of mood and disposition of soul in the man who is reaching out for initiation-knowledge. Please do not misunderstand me. I do not mean that he who is approaching initiation suddenly becomes an entirely transformed person. On the contrary, modern initiation-knowledge must leave a man wholly in the world, capable of continuing his life as when he began. But in the hours and moments dedicated to super-sensible investigation, man becomes, through initiation-knowledge, completely different from what he is in ordinary life. Above all, I would like now to emphasize an important moment which distinguishes initiation-knowledge. The more a man presses forward in his experience of the super-sensible world, the more he feels that the influences from his own corporeality are disappearing, that is to say regarding those things in which this corporeality takes part in ordinary life. Let us ask ourselves, for a moment, how our judgments occur in life. We develop as children, and grow up. Sympathy and antipathy take firm root in our life: sympathy and antipathy with appearances in nature, and, above all, with other human beings. Our body takes part in all this. Sympathy and antipathy—which to a large extent have their basis actually in physical processes—enter quite naturally into all these things. The moment he who is approaching initiation rises into the super-sensible world, he passes into a realm where sympathy and antipathy connected with his bodily nature become more and more foreign to him. He is removed from that with which his corporeality connects him. And when he wishes again to take up ordinary life he must, as it were, deliberately invest in his ordinary sympathies and antipathies, which otherwise occurs quite as a matter of course. When one wakes in the morning, one lives within one's body, one develops the same love for things and human beings, the same sympathy or antipathy which one had before. If one has tarried in the super-sensible world and wishes to return to one's sympathies and antipathies, then one must do it with a struggle, one must, as it were, immerse oneself in one's own corporeality. This removal from one's own corporeality is one of the signs that one has actually made headway. Wide-hearted sympathies and antipathies gradually begin to unfold in one who is treading the path to initiation. In one direction, spiritual development shows itself very strongly, namely in the working of the memory and the power of remembering during initiation-knowledge. We experience ourselves in ordinary life. Our memory, our recollection, is sometimes a little better, sometimes a little worse, but we earn these memories. We have experiences, and we remember them later. This is not so with what we experience in the super-sensible worlds. This we can experience in greatness, in beauty, and in significance—it is experienced, then it is gone. And it must be experienced again if it is again to stand before the soul. It does not impress itself in the memory in the ordinary sense. It impresses itself only if one can first, with all effort, bring what one sees in the super-sensible world into concepts, if one can transfer one's understanding to the super-sensible world. This is very difficult. One must be able to think there, but without the help of the body. Therefore one's concepts must be well grounded in advance, one must have developed before a logical, orderly mind and not always be forgetting one's logic when looking into the super-sensible world. People possessed of primitive clairvoyant faculties are able to see many things; but they forget logic when they are there. And so it is precisely when one has to communicate super-sensible truths to others that one becomes aware of this transformation in the memory in reference to spiritual truths. This shows us how much our physical body is involved in the practice of memory, not of thought but of memory, which indeed always plays over into the super-sensible. If I were to say something personal, it would be this: when I give a lecture, it is different from when others give lectures. In others, what is said is usually drawn from the memory; what one learns, what one thinks, is usually developed out of the memory. But he who is really unfolding super-sensible truths must at that very moment bring them to birth. I can give the same lecture thirty, forty, or fifty times, and for me it is never the same. Of course this may happen in other cases too; but at all events the power to be independent of ordinary memory is very greatly enhanced when this inner stage of development is reached. What I have now related to you concerns the ability to bring form into the etheric body in the head. This then makes it possible for a man to see the time-body, the etheric body, stretching back to his birth, bringing about a very particular frame of mind vis-à-vis the cosmos. One loses one's own corporeality, so to speak, but one gradually becomes accustomed to the cosmos. The consciousness expands, as it were, into the wide spaces of the ether. One no longer contemplates a plant without plunging into its growing. One follows it from root to blossom; one lives in its saps, in its flowering, in its fruiting. One can steep oneself in the life of animals as revealed by their forms, but above all in the life of other human beings. The slightest trait perceived in other human beings will lead one into the whole life of the soul, so that during these super-sensible perceptions one feels not within but outside oneself. But one must always be able to return. This is essential, for otherwise one is an inactive, nebulous mystic, a dreamer—not a knower of the super-sensible worlds. One must be able to live in these higher worlds, but at the same time be able to bring oneself back again, so as to stand firmly on one's own two feet. That is why in speaking of these things I state emphatically that for me as for a good philosopher a knowledge of how shoes and coats are sewn is almost more important than logic. A true philosopher should be a practical human being. One must not be thinking about life if one does not stand within it as a really practical human being. And in the case of one who is seeking super-sensible knowledge this is still more necessary. Knowers of the super-sensible cannot be dreamers or fanatics—people who do not stand firmly on their own two feet. Otherwise one loses oneself because one must really come out of oneself. But this coming-out-of-oneself must not lead to losing oneself. The book, Occult Science, an Outline, was written from such a knowledge as I have described. Then the question is whether one can carry this super-sensible knowledge further. This occurs through further cultivating one's meditation. To begin with, one rests with the meditation upon certain definite ideas or a combination of ideas and thereby strengthens one's life of soul. But this is not enough to enter the super-sensible world fully. Another exercise is necessary. Not only is it necessary to rest with definite ideas, concentrating one's whole soul upon them, but one must be able, at will, to drive these ideas out of one's consciousness again. Just as in material life one can look at some object and then away from it, so in super-sensible development one must learn to concentrate on some idea and then to drive it entirely away. Even in ordinary life this is far from easy. Think how little a man has under his control, to be always impelled by his thoughts. They will often haunt him day in and day out, especially if they are unpleasant. He cannot get rid of them. This is a still more difficult thing to do when we have accustomed ourselves to concentrate upon a particular thought. A thought content upon which we have concentrated begins finally to hold us fast and we must exert every effort to drive it away. But after long practice we shall be able to throw the whole retrospective tableau of life back to birth, this whole etheric body, which I have called the time-body, entirely out of our consciousness. This, of course, is a stage of development towards which we must bring ourselves. We must first mature. By the sweeping away of ideas upon which we have meditated, we must acquire the power to rid ourselves of this colossus, this giant in the soul. This terrible specter of our life between the present moment and birth stands there before us—and we must do away with it. If we eliminate it, a “more wakeful consciousness”—if I may so express it—will arise in us. Consciousness is fully awake but is empty. And then it begins to be filled. Just as the air streams into the lungs when they need it, so there streams into this empty consciousness, in the way I have described, the true spiritual world. This is Inspiration. It is an in-streaming not of some finer substance but of something that is related to substance as negative is to positive. That which is the reverse of substance now pours into a human nature which has become free from the ether. It is important that we can become aware that spirit is not a finer, more ethereal substance. If we speak of substance as positive (we might also speak of it as negative, but that is not the point; these things are relative)—then we speak of spirit as being the negative to the positive. Let me put it thus: suppose I have the large sum of five shillings in my possession. I give one shilling away and then have four shillings left. I give another away—three shillings left, and so on until I have no more. But then I can make debts. If I have a debt of a shilling, then I have less than no shilling! If, through the methods that I have described, I have eliminated the etheric body, I do not enter into a still finer ether, but into something that is the reverse of the ether, as debts are the reverse of assets. Only now I know through experience what spirit is. The spirit pours into us through Inspiration; the first thing that we now experience is what was with our soul and with our spirit in a spiritual world before birth, or rather before conception. This is the pre-existent life of our soul-spirit. Before reaching this point we saw in the ether back to our birth. Now we look beyond conception and birth, out into the world of soul and spirit, and behold ourselves as we were before we came down from spiritual worlds and acquired a physical body from the line of heredity. In initiation-knowledge these things are not philosophical truths that one thinks out: they are experiences, but experiences which have to be earned by means of the preparations I have now indicated. The first truth that comes to us when we have entered the spiritual world is that of the pre-existence of the human soul and the human spirit respectively, and we learn now to behold the eternal directly. For many centuries European humanity has had eyes for only one aspect of eternity—namely, the aspect of immortality. Men have asked only this: what becomes of the soul when it leaves the body at death? This question is the egotistical privilege of men, for men take an interest in what follows death from an egotistical basis. We shall presently see that we can speak of immortality too, but at all events men usually speak of it from an egotistical basis. They are less interested in what preceded birth. They say to themselves: “We are here now. What went before has only worth in knowledge.” But one will not win true worth in knowledge unless one also directs one's attention to existence as it was before birth, or rather, before conception. We need a word in modern parlance with which to complete the idea of eternity. For we should not speak only of immortality; we should speak also of Ungeborenheit—Unborn-ness—a word difficult to translate. Eternity has these two aspects: immortality and unborn-ness. And initiation-knowledge discovers unborn-ness before immortality. A further stage along the path to the super-sensible world can be reached if we now try to make our activity of soul and spirit still freer of the support from the body. To this end we now gradually guide the exercises in meditation and concentration to become exercises for the will. As a concrete example, let me lead you to a simple exercise for strengthening the will. It will help you to be able to study the principle here involved. In ordinary life we are accustomed to think with the course of the world. We let things come to us as they happen. That which comes to us earlier, we think of first, and that which comes to us later, we think of later. And even if we do not think with the course of time in more logical thought, there is always in the background the tendency to keep to the outward, actual course of events. Now in order to exercise our forces of spirit and soul we must get free of the outer cause of things. A good exercise—and one which is at the same time an exercise for the will—is to try to think back over our day's experiences, not as they occurred from morning to evening, but backwards, from evening to morning, entering as much as possible into details. Suppose in this backward review we come to the moment when, during the day, we walked up a staircase. We think of ourselves at the top step, then at the one before the top, and so on, down to the bottom. We go down that staircase backwards in thought. To begin with we will only be in the position to visualize episodes of the day in this backward order, say from six o'clock to three o'clock, or from twelve to nine, and so on to the moment of waking. But gradually we shall acquire a kind of technique by means of which, in the evening or the next morning, we are actually in a position to let a retrospective tableau of the experiences of the day or the day before pass before our soul in pictures. If we are in the position—and we will arrive at it—to free ourselves completely from the kind of thought which follows three-dimensional reality, we will see what a tremendous power our will becomes. We will reach this also if we can arrive at the position where we can experience the notes of a melody backwards, or visualize a drama in five acts, beginning with the fifth, then the fourth, and so on, to the first act. Through all such exercises we strengthen the power of will, for we invigorate it inwardly and free it from its bondage to events in the material world. Here again, exercises I have indicated in previous lectures can be appropriate if we take stock of ourselves and realize that we have acquired this or that habit. We now take ourselves firmly in hand and apply an iron will in order within two years or so to have changed this particular habit into a different one. To take only a simple example: something of a man's character is contained in his handwriting. If we strain ourselves to acquire a handwriting bearing no resemblance to what it was before, this takes a strong inner force. Now this second handwriting must become quite as much a habit, just as fluent as the first. That is only a trivial matter but there are many things whereby the fundamental direction of our will may be changed through our own efforts. Gradually we bring it to the point where not only is the spiritual world received in us as Inspiration, but actually our spirit, freed from the body, is submerged in other spiritual beings outside of us. For true spiritual knowledge is a submerging in spiritual beings who are spiritually all around us when we look back at physical phenomena. If we would know the spiritual, we must first, as it were, get outside ourselves. I have already described this. But then we must also acquire the ability to sink ourselves into things, namely into spiritual things and spiritual beings. We can do this only after we also practice such initiation exercises as I have described, bringing us to the point where our own body is no longer a disturbing element but where we can submerge ourselves in the spirituality of things, where the colors of the plants no longer merely appear to us, but where we plunge into the colors themselves; where we do not only color the plants, but see them color themselves. Not only do we know that the chicory blossom growing by the wayside is blue, when we contemplate it; but we can submerge ourselves inwardly in the blossom itself, in the process whereby it becomes blue. And from that point we can extend our spiritual knowledge more and more. Various symptoms will indicate that these exercises have really been the means of progress. I will mention two, but there are many. The first lies in the fact that we receive a way of viewing the moral world completely different from before. For pure intellectualism, the moral world has something unreal about it. Of course, if a man has abided by the laws of decent behavior in the age of materialism, he will feel it incumbent upon him to do what is right according to well-worn tradition. But even if he does not admit it, he thinks to himself: when I do what is right, there is not so much taking place as when lightning strikes through space or when thunder rolls across the sky. He does not think it real in the same sense. But when one lives within the spiritual world one becomes aware that the moral world-order not only has the reality of the physical world, but has a higher reality. Gradually one learns to understand that this whole age with its physical constituents and processes may perish, may disintegrate, but that the moral influences which flow out of us strongly endure. The reality of the moral world dawns upon us. The physical and the moral world, “being” and “becoming,” become one. We actually experience that the world has moral laws as objective laws. This increases responsibility in relation to the world. It gives us a totally different consciousness—a consciousness of which present-day humanity stands in sore need. For modern mankind looks back to the earth's beginning, where the earth is supposed to have been formed out of a primeval mist. Life is thought to have arisen out of the same mist, then man himself, and from man—as a Fata Morgana—the world of ideas. Mankind looks ahead to a death of warmth, to a time when all that mankind lives within must become submerged in a great tomb, and they need a knowledge of the moral world-order which can only be received fundamentally through fully obtaining spiritual knowledge. This I can only indicate. But the other aspect is that one cannot reach this Intuitive knowledge, this submerging in outer things, without passing through intense suffering, much more intense than the pain of which I had to speak when I characterized Imaginative knowledge, when I said that through one's own efforts one must find the way back into one's sympathies and antipathies—and that inevitably means pain. But now pain becomes a cosmic experiencing of all suffering that rests upon the ground of existence. One can easily ask why the Gods or God created suffering. Suffering must be there if the world is to arise in its beauty. That we have eyes—I will use popular language here—is simply due to the fact that to begin with, in a still undifferentiated organism, the organic forces were excavated which lead to sight and which, in their final metamorphosis, become the eye. If we were still aware today of the minute processes which go on in the retina in the act of sight, we should realize that even this is fundamentally the existence of a latent pain. All beauty is grounded in suffering. Beauty can only be developed from pain. And one must be able to feel this pain, this suffering. Only through this can we really find our way into the super-sensible world, by going through this pain. To a lesser degree, and at a lower stage of knowledge, this can already be said. He who has acquired even a little knowledge will admit to you: for the good fortune and happiness I had in life, I have my destiny to thank; but only through pain and suffering have I been able to acquire my knowledge. If one realizes this already at the beginning of a more elementary knowledge, it can become a much higher experience when one becomes master of oneself, when one reaches out through the pain that is experienced as cosmic pain to the stage of “neutral” experience in the spiritual world. One must work through to a point where one lives with the coming-into-existence and the essential nature of all things. This is Intuitive knowledge. But then one is also completely within an experience of knowledge that is no longer bound to the body; thus one can return freely to the body, to the material world, to live until death, but now fully knowing what it means to be real, to be truly real in soul and spirit, outside the body. If one has understood this, then one has a picture of what happens when the physical body is abandoned at death, and what it means to pass through the gate of death. Having risen to Intuitive knowledge, one has foreknowledge, which is also experience, of the reality that the soul and spirit pass into a world of soul and spirit when the body is abandoned at death. One knows what it is to function in a world where no support comes from the body. Then, when this knowledge has been embodied in concepts, one can return again to the body. But the essential thing is that one learns to live altogether independently of the body, and thereby acquires knowledge of what happens when the body can no longer be used, when one lays it aside at death and passes over into a world of soul and spirit. And again, what results from initiation-knowledge on the subject of immortality is not a philosophical speculation but an experience—or rather a pre-experience—if I may so express myself. One knows what one will then be. One experiences, not the full reality, but a picture of reality, which in a certain way corresponds with the full reality of death. One experiences immortality. Here too, you see, experience is drawn into and becomes part of knowledge. I have tried now to describe to you how one rises through Imagination to Inspiration and Intuition, and how one finally through this becomes acquainted with one's full reality. In the body one learns to perceive oneself, so long as one remains within that body. The soul and spirit must be freed from the body, for then one becomes for the first time a whole man. Through what we perceive through the body and its senses, through the ordinary thinking which, arising from the sense-experiences, is bound up with the body, especially with the nerve-sense system, one becomes acquainted with only a limb of man. We cannot know the whole, full man unless we have the will to rise to the modes of knowledge which come out of initiation-science. Once again I would like to emphasize: if these things are investigated, everyone who approaches the results with an unprejudiced mind can understand them with ordinary, healthy human reason—just as he can understand what astronomers or biologists have to say about the world. The results can be tested, and indeed one will find that this testing is the first stage of initiation-knowledge. For initiation-knowledge, one must first have an inclination towards truth, because truth, not untruth and error, is one's object. Then one who follows this path will be able, if destiny makes it possible, to penetrate further and further into the spiritual world during this earthly life. In our day, and in a higher way, the call inscribed over the portal of a Greek temple must be fulfilled: “Man, know thyself!” Those words were not a call to man to retreat into his inner life but a demand to investigate into the being of man: into the being of immortality = body; into the being of unborn-ness = immortal spirit; and into the mediator between the earth, the temporal, and the spirit = soul. For the genuine, the true man consists of body, soul, and spirit. The body can know only the body; the soul can know only the soul; the spirit can know only the spirit. Thus we must seek to find active spirit within us in order to be able to perceive the spirit also in the world. |

| 214. The Mystery of the Trinity: Meditation: The Path to Higher Knowledge

20 Aug 1922, Oxford Translated by James H. Hindes Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| 214. The Mystery of the Trinity: Meditation: The Path to Higher Knowledge

20 Aug 1922, Oxford Translated by James H. Hindes Rudolf Steiner |

|---|