| 18. The Riddles of Philosophy: The Radical World Conceptions

Translated by Fritz C. A. Koelln Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| They show most distinctly the direction in which these personalities advance because one can learn from them the change that has been wrought by the time interval that lies between them. Feuerbach went through Hegel's philosophy. He derived the strength from this experience to develop his own opposing view. He no longer felt disturbed by Kant's question of whether we are in fact entitled to attribute reality to the world that we perceive, or whether this world merely existed in our minds. |

| [ 4 ] To develop a world conception that was as much the opposite of Hegel's as that of Feuerbach, a personality was necessary that was as different from Hegel as was Feuerbach. |

| That thinking is destined to penetrate to the essence of things is a conviction he adopted from Hegel's world conception, but he does not, like Hegel, tend to let thinking lead to results and a thought structure. |

| 18. The Riddles of Philosophy: The Radical World Conceptions

Translated by Fritz C. A. Koelln Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

[ 1 ] At the beginning of the forties of the last century a man who had previously thoroughly and intimately penetrated the world conceptions of Hegel, now forcefully attacked them. This man was Ludwig Feuerbach (1804–1872). The declaration of war against the philosophy in which he had grown up is given in a radical form in his essay, Preliminary Theses for the Reformation of Philosophy (1842), and Principle of the Philosophy of the Future (1843). The further development of his thoughts can be followed in his other writings, The Essence of Christianity (1841), The Nature of Religion (1845), and Theogony (1857). In the activity of Ludwig Feuerbach a process is repeated in the field of the science of the spirit that had happened almost a century earlier (1759) in the realm of natural science through the activity of Caspar Friedrich Wolff. Wolff's work had meant a reform of the idea of evolution in the field of biology. How the idea of evolution was understood before Wolff can be most distinctly learned from the views of Albrecht von Haller, a man who opposed the reform of this conception most vehemently. Hailer, who is quite rightly respected by physiologists as one of the most significant spirits of this science, could not conceive the development of a living being in any other form than that in which the germ already contains all parts that appear in the course of life, but on a small scale and perfectly pre-formed. Evolution, then, is supposed to be an unfolding of something that was there in the first place but was hidden from perception because of its smallness, or for other reasons. If this view is consistently upheld, there is no development of anything new. What happens is merely that something that is concealed, encased, is continuously brought to the light of day. Hailer stood quite rigorously for this view. In the first mother, Eve, the whole human race was contained, concealed on a small scale. The human germs have only been unfolded in the course of world history. The same conception is also expressed by the philosopher Leibniz (1646–1716):

Wolff opposed this idea of evolution with one of his own in Theoria Generationis, which appeared in 1759. He proceeded from the supposition that the members of an organism that appear in the course of life have not existed previously but come into being at the moment they become perceptible as real new formations. Wolff showed that the egg contains nothing of the form of the developed organism but that its development constitutes a series of new formations. This view made the conception of a real becoming possible, for it showed how something comes into being that had not previously existed and that therefore “comes to be” in the true sense of the word. [ 2 ] Haller's view really denies becoming as it admits only a continuous process of becoming visible of something that had previously existed. This scientist had opposed the idea of Wolff with the peremptory decree, “There is no becoming” (Nulla est epigenesis). He had, thereby, actually brought about a situation in which Wolff s view remained unconsidered for decades. Goethe blames this encasement theory for the resistance with which his endeavors to explain living beings was met. He had attempted to comprehend the formations in organic nature through the study of the process of their development, which he understood entirely in the sense of a true evolution, according to which the newly appearing parts of an organism have not already had a previously concealed existence, but do indeed come into being when they appear. He writes in 1817 that this attempt, which was a fundamental presupposition of his essay on the metamorphosis of plants written in 1790, “was received in a cold, almost hostile manner, but such reluctance was quite natural. The encasement theory, the concept of pre-formation, of a successive development of what had existed since Adam's times, had in general taken possession even of the best minds.” One could see a remnant of the old encasement theory even in Hegel's world conception. The pure thought that appears in the human mind was to have been encased in all phenomena before it came to its perceptible form of existence in man. Before nature and the individual spirit, Hegel places his pure thought that should be, as it were, “the representation of God as he was according to his eternal essence before the creation” of the world. The development of the world is, therefore, presented as an unwrapping of pure thought. The protest of Ludwig Feuerbach against Hegel's world conception was caused by the fact that Feuerbach was unable to acknowledge the existence of the spirit before its real appearance in man, just as Caspar Friedrich Wolff had been unable to admit that the parts of the living organism should have been pre-formed in the egg. Just as Wolff saw spontaneous formations in the organs of the developed organism, so did Feuerbach with respect to the individual spirit of man. This spirit is in no way there before its perceptible existence; it comes into being only in the moment it appears. According to Feuerbach, it is unjustified to speak of an all-embracing spirit, of a being in which the individual spirit has its roots. No reason-endowed being exists prior to its appearance in the world that would shape matter and the perceptible world, and in this way cause the appearance of man as its visible afterimage. What exists before the development of the human spirit consists of mere matter and blind forces that form a nervous system out of themselves concentrated in the brain. In the brain something comes into existence that is a completely new formation, something that has never been before: the human soul, endowed with reason. For such a world conception there is no possibility to derive the processes and things from a spiritual originator because, according to this view, a spiritual being is a new formation through the organization of the brain. If man projects a spiritual element into the external world, then he imagines arbitrarily that a being like the one that is the cause of his own actions exists outside of himself and rules the world. Any spiritual primal being must first be created by man through his fantasy; the things and processes of the world give us no reason to assume its original existence. It is not the original spirit being that has created man after his image, but man has formed a fantasy of such a primal entity after his own image. This is Feuerbach's conviction. “Man's knowledge of God is man's knowledge of himself, of his own nature. Only the unity of being and consciousness is truth. Where God's consciousness is, there is also God's being: it is, therefore, in man” (The Essence of Christianity, 1841). Man does not feel strong enough to rest within himself; he therefore created an infinite being after his own image to revere and to worship. Hegel's world conception had eliminated all other qualities from the supreme being, but it had retained the element of reason. Feuerbach removes this element also and with this step he removes the supreme being itself. He replaces the wisdom of God completely by the wisdom of the world. As a necessary turning point in the development of world conception, Feuerbach declares the “open confession and admission that the consciousness of God is nothing but the consciousness of humanity,” and that man is “incapable of thinking, divining, imagining, feeling, believing, willing, loving and worshipping as an absolute divine being any other being than the human being.” There is an observation of nature and an observation of the spirit, but there is no observation of the nature of God. Nothing is real but the factual.

Indeed, this can be summed up as follows. The phenomenon of thinking appears in the human organism as a new formation, but we are not justified to imagine that this thought had existed before its appearance in any form invisibly encased in the world. One should not attempt to explain the condition of something actually given by deriving it from something that is assumed as previously existing. Only the factual is true and divine, “what is immediately sure of itself, that-which directly speaks for and convinces of itself, that which immediately effects the assertion of its existence, what is absolutely decided, incapable of doubt, clear as sunlight. But only the sensual is of such a clarity. Only where the sensual begins does all doubt and quarrel cease. The secret of immediate knowledge is sensuality.” Feuerbach's credo has its climax in the words, “To make philosophy the concern of humanity was my first endeavor, but whoever decides upon a path in this direction will finally be led with necessity to make man the concern of philosophy.” “The new philosophy makes man, and with him nature as the basis of man, the only universal and ultimate object of philosophy; it makes an anthropology that includes physiology in it—the universal science.” Feuerbach demands that reason is not made the basis of departure at the beginning of a world conception but that it should be considered the product of evolution, as a new formation in the human organism in which it makes its actual appearance. He has an aversion to any separation of the spiritual from the physical because it can be understood in no other way than as a result of the development of the physical.

[ 3 ] Feuerbach drew attention to Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, a thinker who died in 1799 and who must be considered a precursor of a world conception that found expression in thinkers like Feuerbach. Lichtenberg's stimulating and thought-provoking conceptions were less fruitful for the nineteenth century probably because the powerful thought structures of Fichte, Schelling and Hegel overshadowed everything. They overshadowed the spiritual development to such a degree that ideas that were expressed aphoristically as strokes of lightning, even if they were as brilliant as Lichtenberg's, could be overlooked. We only have to be reminded of a few statements of this important person to see that in the thought movement introduced by Feuerbach the spirit of Lichtenberg experiences a revival.

If Lichtenberg had combined such original flashes of thought with the ability to develop a harmoniously rounded world conception, he could not have remained unnoticed to the degree that he did. In order to form a world conception, it is not only necessary to show superiority of mind, as Lichtenberg did, but also the ability to form ideas in their interconnection in all directions and to round them plastically. This faculty he lacked. His superiority is expressed in an excellent judgment concerning the relation of Kant to his contemporaries:

How akin in spirit Feuerbach could feel to Lichtenberg becomes especially clear if one compares the views of both thinkers with respect to the relation of their world conceptions to practical life. The lectures Feuerbach gave to a number of students during the winter of 1848 on The Nature of Religion closed with these words:

Whoever, like Feuerbach, bases all world conception on the knowledge of nature and man, must also reject all direction and duties in the field of morality that are derived from a realm other than man's natural inclinations and abilities, or that set aims that do not entirely refer to the sensually perceptible world. “My right is my lawfully recognized desire for happiness; my duty is the desire for happiness of others that I am compelled to recognize.” Not in looking with expectation toward a world beyond do I learn what I am to do, but through the contemplation of this one. Whatever energy I spend to fulfill any task that refers to the next world, I have robbed from this world for which I am exclusively meant. “Concentration on this world” is, therefore, what Feuerbach demands. We can read similar expressions in Lichtenberg's writings. But just such passages in Lichtenberg are always mixed with elements that show how rarely a thinker who lacks the ability to develop his ideas in himself harmoniously succeeds in following an idea into its last consequences. Lichtenberg does, indeed, demand concentration on this world, but he mixes conceptions that refer to the next even into the formulation of this demand.

Comparisons like this one between Lichtenberg and Feuerbach are significantly instructive for the historical evolution of man's world conception. They show most distinctly the direction in which these personalities advance because one can learn from them the change that has been wrought by the time interval that lies between them. Feuerbach went through Hegel's philosophy. He derived the strength from this experience to develop his own opposing view. He no longer felt disturbed by Kant's question of whether we are in fact entitled to attribute reality to the world that we perceive, or whether this world merely existed in our minds. Whoever upholds the second possibility can project into the true world behind the perceptual representations all sorts of motivating forces for man's actions. He can admit a supernatural world order as Kant had done. But whoever, like Feuerbach, declares that the sensually perceptible alone is real must reject every supernatural world order. For him there is no categorical imperative that could somehow have its origin in a transcendent world; for him there are only duties that result from the natural drives and aims of man. [ 4 ] To develop a world conception that was as much the opposite of Hegel's as that of Feuerbach, a personality was necessary that was as different from Hegel as was Feuerbach. Hegel felt at home in the midst of the full activity of his contemporary life. To influence the actual life of the world with his philosophical spirit appeared to him a most attractive task. When he asked for his release from his professorship at Heidelberg in order to accept another chair in Prussia, he confessed that he was attracted by the expectation of finding a sphere of activity where he was not entirely limited to mere teaching, but where it would also be possible for him to affect the practical life. “It would be important for him to have the expectation of moving, with advancing age, from the precarious function of teaching philosophy at a university to another activity and to become useful in such a capacity.” A man who has the inclinations and convictions of a thinker must live in peace with the shape that the practical life of his time has taken on. He must find the ideas reasonable by which this life is permeated. Only from such a conviction can he derive the enthusiasm that makes him want to contribute to the consolidation of its structure. Feuerbach was not kindly inclined toward the life of his time. He preferred the restfulness of a secluded place to the bustle of what was for him “modern life.” He expresses himself distinctly on this point:

From his seclusion Feuerbach believed himself to be best able to judge what was not natural with regard to the shape that the actual human life assumed. To cleanse life from these illusions, and what was carried into it by human illusions, was what Feuerbach considered to be his task. To do this he had to keep his distance from life as much as possible. He searched for the true life but he could not find it in the form that life had taken through the civilization of the time. How sincere he was with his “concentration on this world” is shown by a statement he made concerning the March revolution. This revolution seemed to him a fruitless enterprise because the conceptions that were behind it still contained the old belief in a world beyond.

Only a personality who is convinced that he carries within him the harmony of life that man needs can, in the face of the deep hostility that existed between him and the real world, utter the hymns in praise of reality that Feuerbach expressed. Such a conviction rings out of words like these:

Only a personality like this could search for all those forces in man himself that the others wanted to derive from external powers. [ 5 ] The birth of thought in the Greek world conception had had the effect that man could no longer feel himself as deeply rooted in the world as had been possible with the old consciousness in the form of picture conceptions. This was the first step in the process that led to the formation of an abyss between man and the world. A further stage in this process consisted in the development of the mode of thinking of modern natural science. This development tore nature and the human soul completely apart. On the one side, a nature picture had to arise in which man in his spiritual-psychical essence was not to be found, and on the other, an idea of the human soul from which no bridge led into nature. In nature one found law-ordered necessity. Within its realm there was no place for the elements that the human soul finds within: The impulse for freedom, the sense for a life that is rooted in a spiritual world and is not exhausted within the realm of sensual existence. Philosophers like Kant escaped the dilemma only by separating both worlds completely, finding a knowledge in the one, and in the other, belief. Goethe, Schiller, Fichte, Schelling and Hegel conceived the idea of the self-conscious soul to be so comprehensive that it seemed to have its root in a higher spirit nature. In Feuerbach, a thinker arises who, through the world picture that can be derived from the modern mode of conception of natural science, feels compelled to deprive the human soul of every trait contradictory to the nature picture. He views the human soul as a part of nature. He can only do so because, in his thoughts, he has first removed everything in the soul that disturbed him in his attempt to acknowledge it as a part of nature. Fichte, Schelling and Hegel took the self-conscious soul for what it was; Feuerbach changes it into something he needs for his world picture. In him, a mode of conception makes its appearance that is overpowered by the nature picture. This mode of thinking cannot master both parts of the modern world picture, the picture of nature and that of the soul. For this reason, it leaves one of them, the soul picture, completely unconsidered. Wolff's idea of “new formation” introduces fruitful thought impulses to the nature picture. Feuerbach utilizes these impulses for the spirit-science that can only exist, however, by not admitting the spirit at all. Feuerbach initiates a trend of modern philosophy that is helpless in regard to the most powerful impulse of the modern soul life, namely, man's active self-consciousness. In this current of thought, that impulse is dealt with, not merely as an incomprehensible element, but in a way that avoids the necessity of facing it in its true form, changing it into a factor of nature, which, to an unbiased observation, it really is not. [ 6 ] “God was my first thought, reason my second and man my third and last one.” With these words Feuerbach describes the path along which he had gone, from a religious believer to a follower of Hegel's philosophy, and then to his own world conception. Another thinker, who, in 1834, published one of the most influential books of the century, The Life of Jesus, could have said the same thing of himself. This thinker was David Friedrich Strauss (1808– 1874). Feuerbach started with an investigation of the human soul and found that the soul had the tendency to project its own nature into the world and to worship it as a divine primordial being. He attempted a psychological explanation for the genesis of the concept of God. The views of Strauss were caused by a similar aim. Unlike Feuerbach, however, he did not follow the path of the psychologist but that of the historian. He did not, like Feuerbach, choose the concept of God in general in its all-embracing sense for the center of his contemplation, but the Christian concept of the “God incarnate,” Jesus. Strauss wanted to show how humanity arrived at this conception in the course of history. That the supreme divine being reveals itself to the human spirit was the conviction of Hegel's world conception. Strauss had accepted this, too. But, in his opinion, the divine idea, in all its perfection, cannot realize itself in an individual human being. The individual person is always merely an imperfect imprint of the divine spirit. What one human being lacks in perfection is presented by another. In examining the whole human race one will find in it, distributed over innumerable individuals, all perfection's belonging to the deity. The human race as a whole, then, is God made flesh, God incarnate. This is, according to Strauss, the true thinker's concept of Jesus. With this viewpoint Strauss sets out to criticize the Christian concept of the God incarnate. What, according to this idea, is distributed over the whole human race, Christianity attributes to one personality who is supposed to have existed once in the course of history.

Supported by careful investigations concerning the historical foundation of the Gospels, Strauss attempts to prove that the conceptions of Christianity are a result of religious fantasy. Through this faculty the religious truth that the human race is God incarnate was dimly felt, but it was not comprehended in clear concepts but merely expressed in poetic form, in a myth. For Strauss, the story of the Son of God thus becomes a myth in which the idea of humanity was poetically treated long before it was recognized by thinkers in the form of pure thought. Seen from this viewpoint, all miraculous elements of the history of Christianity become explainable without forcing the historian to take refuge in the trivial interpretation that had previously often been accepted. Earlier interpretations had often seen in those miracles intentional deceptions and fraudulent tricks to which either the founder of the religion himself had allegedly resorted in order to achieve the greatest possible effect of his doctrine, or which the apostles were supposed to have invented for this purpose. Another view, which wanted to see all sorts of natural events in the miracles, was also thereby eliminated. The miracles are now seen as the poetic dress for real truths. The story of humanity rising above its finite interests and everyday life to the knowledge of divine truth and reason is represented in the picture of the dying and resurrected saviour. The finite dies to be resurrected as the infinite. [ 7 ] We have to see in the myths of ancient peoples a manifestation of the picture consciousness of primeval times out of which the consciousness of thought experience developed. A feeling for this fact arises in the nineteenth century in a personality like Strauss. He wants to gain an orientation concerning the development and significance of the life of thought by concentrating on the connection of world conception with the mythical thinking of historical times. He wants to know in what way the myth-making imagination still affects modern world conception. At the same time, he aspires to see the human self-consciousness rooted in an entity that lies beyond the individual personality by thinking of all humanity as a manifestation of the deity. In this manner, he gains a support for the individual human soul in the general soul of humanity that unfolds in the course of historical evolution. [ 8 ] Strauss becomes even more radical in his book, The Christian Doctrine in the Course of Its Historical Development and Its Struggle with Modern Science, which appeared in the years 1840 and 1841. Here he intends to dissolve the Christian dogmas in their poetic form so as to obtain the thought content of the truths contained in them. He now points out that the modern consciousness is incompatible with the consciousness that clings to the old mythological picture representation of the truth.

These views of Strauss produced an enormous uproar. It was deeply resented that those representing the modern world conception were no longer satisfied in attacking only the basic religious conceptions in general, but, equipped with all scientific means of historical research, attempted to eliminate the irrelevancy about which Lichtenberg had once said that it consisted of the fact that “human nature had submitted even to the yoke of a book.” He continued:

Strauss was discharged from his position as a tutor at the Seminary of Tuebingen because of his book, The Life of Jesus, and when he then accepted a professorship in theology at the University of Zurich, the peasants came to meet him with threshing flails in order to make the position of the dissolver of the myth impossible and to force his retirement. [ 9 ] Another thinker, Bruno Bauer (1809–1882), in his criticism of the old world conception from the standpoint of the new, went far beyond the aim that Strauss had set for himself. He held the same view as Feuerbach, that man's nature is also his supreme being and any other kind of a supreme being is only an illusion created after man's image and set above himself. But Bauer goes further and expresses this opinion in a grotesque form. He describes how he thinks the human ego came to create for itself an illusory counter-image, and he uses expressions that show they are not inspired by the wish for an intimate understanding of the religious consciousness as was the case with Strauss. They have their origin in the pleasure of destruction. Bauer says:

Bruno Bauer is a personality who sets out to test his impetuous thinking critically against everything in existence. That thinking is destined to penetrate to the essence of things is a conviction he adopted from Hegel's world conception, but he does not, like Hegel, tend to let thinking lead to results and a thought structure. His thinking is not productive, but critical. He would have felt a definite thought or a positive idea as a limitation. He is unwilling to limit the power of critical thought by taking his departure from a definite point of view as Hegel had done.

This is the credo of the Critique of World Conception to which Bruno Bauer confesses. This “critique” does not believe in thoughts and ideas but in thinking alone. “Only now has man been discovered,” announces Bauer triumphantly, for now man is bound by nothing except his thinking. It is not human to surrender to a non-human element, but to work everything out in the melting pot of thinking. Man is not to be the afterimage of another being, but above all, he is to be “a human being,” and he can become human only through his thinking. The thinking man is the true man. Nothing external, neither religion nor right, neither state nor law, etc., can make him into a human being, but only his thinking. The weakness of a thinking that strives to reach the self-consciousness but cannot do so is demonstrated in Bauer. [ 10 ] Feuerbach had declared the “human being to be man's supreme being; Bruno Bauer maintained that he had discovered it for the first time through his critique of world conception; Max Stirner (1806–1856) set himself the task of approaching this “human being” completely without bias and without presupposition in his book, The Only One and His Possession, which appeared in 1845. This is Stirner's judgment:

Stirner opposes the view of Feuerbach with his violent contradiction:

The individual human ego does not consider itself from its own standpoint but from the standpoint of a foreign power. A religious man claims that there is a divine supreme being whose afterimage is man. He is possessed by this supreme being. The Hegelian says that there is a general world reason and it realizes itself to reach its climax in the human ego. The ego is therefore possessed by this world reason. Feuerbach maintains that there is a nature of the human being and every particular person is an individualized afterimage of this nature. Every individual is thereby possessed by the idea of the “nature of humanity.” For only the individual man is really existing, not the “generic concept of humanity” by which Feuerbach replaces the divine being. If, then, the individual man places the “genus man” above himself, he abandons himself to an illusion, just as much as when he feels himself dependent on a personal God. For Feuerbach, therefore, the commandments the Christian considers as given by God, and which for this reason he accepts as valid, change into commandments that have their validity because they are in accordance with the general idea of humanity. Man now judges himself morally by asking the question: Do my actions as an individual correspond to what is adequate to the nature of humanity in general? For Feuerbach says:

There are, then, general human powers, and ethics is one of them. It is sacred in and for itself; the individual has to submit to it. The individual is not to will what it decides out of its own initiative, but what follows from the direction of the sacred ethics. The individual is possessed by this ethics. Stirner characterizes this view as follows:

But such a supreme being is also thinking, which has been elevated to be God by the critique of world conception. Stirner cannot accept this either.

Every thought is also produced by the individual ego of an individual, even the thought of one's own being, and when man means to know his own ego and wants to describe it according to its nature, he immediately brings it into dependence on this nature. No matter what I may invent in my thinking, as soon as I determine and define myself conceptually, I make myself the slave of the result of the definition, the concept. Hegel made the ego into a manifestation of reason, that is to say, he made it dependent on reason. But all such generalities cannot be valid with regard to the ego because they all have their source in the ego. They are caused by the fact that the ego is deceived by itself. It is really not dependent, for everything on which it could depend must first be produced by the ego. The ego must produce something out of itself, set it above itself and allow it to turn into a spectre that haunts its own originator.

In reality, no thinking can approach what lives within me as “I.” I can reach everything with my thinking; only my ego is an exception in this respect. I cannot think it; I can only experience it. I am not will; I am not idea; I am that no more than the image of a deity. I make all other things comprehensible to myself through thinking. The ego I am. I have no need to define and to describe myself because I experience myself in every moment. I need to describe only what I do not immediately experience, what is outside myself. It is absurd that I should also have to conceive myself as a thought, as an idea, since I always have myself as something. If I face a stone, I may attempt to explain to myself what this stone is. What I am myself, I need not explain; it is given in my life. Stirner answers to an attack against his book:

Stirner, in an essay written in 1842, The Untrue Principle of Our Education, or Humanism and Realism, had already expressed his conviction that thinking cannot penetrate as far as the core of the personality. He therefore considers it an untrue educational principle if this core of the personality is not made the objective of education, but when knowledge as such assumes this position in a one-sided way.

The personality of the individual human being can alone contain the source of his actions. The moral duties cannot be commandments that are given to man from somewhere, but they must be aims that man sets for himself. Man is mistaken if he believes that he does something because he follows a commandment of a general code of sacred ethics. He does it because the life of his ego drives him to it. I do not love my neighbor because I follow a sacred commandment of neighborly love, but because my ego draws me to my neighbor. It is not that I am to love him; I want to love him. What men have wanted to do they have placed as commandments above themselves. On this point Stirner can be most easily understood. He does not deny moral action. What he does deny is the moral commandment. If man only understands himself rightly, then a moral world order will be the result of his actions. Moral prescriptions are a spectre, an idée fixe, for Stirner. They prescribe something at which man arrives all by himself if he follows entirely his own nature. The abstract thinkers will, of course, raise the objection, “Are there not criminals?” These abstract thinkers anticipate general chaos if moral prescriptions are not sacred to man. Stirner could reply to them, “Are there not also diseases in nature? Are they not produced in accordance with eternal unbreakable laws just as everything that is healthy?” As little as it will ever occur to any reasonable person to reckon the sick with the healthy because the former is, like the latter, produced through natural laws, just as little would Stirner count the immoral with the moral because they both come into being when the individual is left to himself. What distinguishes Stirner from the abstract thinkers, however, is his conviction that in human life morality will be dominating as much as health is in nature, when the decision is left to the discretion of individuals. He believes in the moral nobility of human nature, in the free development of morality out of the individuals. It seems to him that the abstract thinkers do not believe in this nobility, and he is, therefore, of the opinion that they debase the nature of the individual to become the slave of general commandments, the corrective scourges of human action. There must be much evil depravity at the bottom of the souls of these “moral persons,” according to Stirner, because they are so insistent in their demands for moral prescriptions. They must indeed be lacking love because they want love to be ordered to them as a commandment that should really spring from them as spontaneous impulse. Only twenty years ago it was possible that the following criticism could be made in a serious book:

This only proves how easily Stirner can be misunderstood as a result of his radical mode of expression because, to him, the human individual was considered to be so noble, so elevated, unique and free that not even the loftiest thought world was supposed to reach up to it. Thanks to the endeavors of John Henry Mackay, we have today a picture of his life and his character. In his book, Max Stirner, His Life and His Work (Berlin, 1898), he has summed up the complete result of his research extending over many years to arrive at a characterization of Stirner who was, in Mackay's opinion, “The boldest and most consistent of all thinkers.” [ 11 ] Stirner, like other thinkers of modern times, is confronted with the self-conscious ego, challenging comprehension. Others search for means to comprehend this ego. The comprehension meets with difficulties because a wide gulf has opened up between the picture of nature and that of the life of the spirit. Stirner leaves all that without consideration. He faces the fact of the self-conscious ego and uses every means at his disposal to express this fact. He wants to speak of the ego in a way that forces everyone to look at the ego for himself, so that nobody can evade this challenge by claiming that the ego is this or the ego is that. Stirner does not want to point out an idea or a thought of the ego, but the living ego itself that the personality finds in itself. [ 12 ] Stirner's mode of conception, as the opposite pole to that of Goethe, Schiller, Fichte, Schelling and Hegel, is a phenomenon that had to appear with a certain necessity in the course of the development of mode2rn world conception. Stirner became aware of the self-conscious ego with an inescapable, piercing intensity. Every thought production appeared to him in the same way in which the mythical world of pictures is experienced by a thinker who wants to seize the world in thought alone. Against this intensely experienced fact, every other world content that appeared in connection with the self-conscious ego faded away for Stirner. He presented the self-conscious ego in complete isolation. [ 13 ] Stirner does not feel that there could be difficulties in presenting the ego in this manner. The following decades could not establish any relationship to this isolated position of the ego. For these decades are occupied above all with the task of forming the nature picture under the influence of the mode of thought of natural science. After Stirner had presented the one side of modern consciousness, the fact of the self-conscious ego, the age at first withdraws all attention from this ego and turns to the picture of nature where this “ego” is not to be found. [ 14 ] The first half of the nineteenth century had born its world conception out of the spirit of idealism. Where a bridge is laid to lead to natural science, as it is done by Schelling, Lorenz Oken (1779–1851) and Henrik Steffens (1773–1845), it is done from the viewpoint of the idealistic world conception and in its interest. So little was the time ready to make thoughts of natural science fruitful for world conceptions that the ingenious conception of Jean Lamarck pertaining to the evolution of the most perfect organisms out of the simple one, which was published in 1809, drew no attention at all. When in 1830 Geoffroy de St. Hilaire presented the idea of a general natural relationship of all forms of organisms in his controversy with Couvier, it took the genius of Goethe to see the significance of this idea. The numerous results of natural science that were contributed in the first half of the century became new world riddles for the development of world conception when Charles Darwin in 1859, opened up new aspects for an understanding of nature with his treatment of the world of living organisms. |

| 322. The Boundaries of Natural Science: Lecture II

28 Sep 1920, Dornach Translated by Frederick Amrine, Konrad Oberhuber Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| It drew on the one hand certain materialistic and on the other hand certain positive theological conclusions from Hegel's thought. And even if one considers the Hegelian center headed by the amiable Rosenkranz, even there one cannot find Hegel's philosophy as Hegel himself had conceived it. |

| In two phenomena above all we notice the uselessness of Hegelianism for social life. One of those who studied Hegel most intensively, who brought Hegel fully to life within himself, was Karl Marx. And what is it that we find in Marx? A remarkable Hegelianism indeed! Hegel up upon the highest peak of the conceptual world—Hegel upon the highest peak of Idealism—and the faithful student, Karl Marx, immediately transforming the whole into its direct opposite, using what he believed to be Hegel's method to carry Hegel's truths to their logical conclusions. |

| 322. The Boundaries of Natural Science: Lecture II

28 Sep 1920, Dornach Translated by Frederick Amrine, Konrad Oberhuber Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

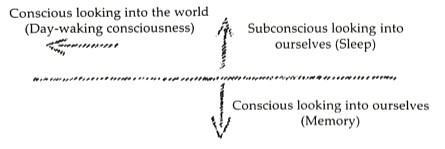

It must be answered, not to meet a human “need to know” but to meet man's universal need to become fully human. And in just what way one can strive for an answer, in what way the ignorabimus can be overcome to fulfil the demands of human evolution—this shall be the theme of our course of lectures as it proceeds. To those who demand of a cycle of lectures with a title such as ours that nothing be introduced that might interfere with the objective presentation of ideas, I would like, since today I shall have to mention certain personalities, to say the following. The moment one begins to represent the results of human judgment in their relationship to life, to full human existence, it becomes inevitable that one indicate the personalities with whom the judgments originated. Even in a scientific presentation, one must remain within the sphere in which the judgment arises, within the realm of human struggling and striving toward such a judgment. And especially since the question we want above all to answer is: what can be gleaned from modern scientific theories that can become a vital social thinking able to transform thought into impulses for life?—then one must realize that the series of considerations one undertakes is no longer confined to the study and the lecture halls but Stands rather within the living evolution of humanity. Behind everything with which I commenced yesterday, the modern striving for a mathematical-mechanical world view and the dissolution of that world view, behind that which came to a climax in 1872 in the famous speech by the physiologist, du Bois-Reymond, concerning the limits of natural science, there stands something even more important. It is something that begins to impress itself upon us the moment we want to begin to speak in a living way about the limits of natural science. A personality of extraordinary philosophical stature still looks over to us with a certain vitality out of the first half of the nineteenth century: Hegel. Only in the last few years has Hegel begun to be mentioned in the lecture halls and in the philosophical literature with somewhat more respect than in the recent past. In the last third of the nineteenth century the academic world attacked Hegel outright, yet one could demonstrate irrefutably that Eduard von Hartmann had been quite right in claiming that during the 1880s only two university lecturers in all of Germany had actually read him. The academics opposed Hegel but not on philosophical grounds, for as a philosopher they hardly knew him. Yet they knew him in a different way, in a way in which we still know him today. Few know Hegel as he is contained, or perhaps better said, as his world view is contained, in the many volumes that sit in the libraries. Those who know Hegel in this original form so peculiar to him are few indeed. Yet in certain modified forms he has become in a sense the most popular philosopher the world has ever known. Anyone who participates in a workers' meeting today or, even better, anyone who had participated in one during the last few decades and had heard what was discussed there; anyone with any sense for the source of the mode of thinking that had entered into these workers' meetings, who really knew the development of modern thought, could see that this mode of thinking had originated with Hegel and flowed through certain channels out into the broadest masses. And whoever investigated the literature and philosophy of Eastern Europe in this regard would find that the Hegelian mode of thinking had permeated to the farthest reaches of Russian cultural life. One thus could say that, anonymously, as it were, Hegel has become within the last few decades perhaps one of the most influential philosophers in human history. On the other hand, however, when one perceives what has come to be recognized by the broadest spectrum of humanity as Hegelianism, one is reminded of the portrait of a rather ugly man that a kind artist painted in such a way as to please the man's family. As one of the younger sons, who had previously paid little attention to the portrait, grew older and really observed it for the first time, he said: “But father, how you have changed!” And when one sees what has become of Hegel one might well say: “Dear philosopher, how you have changed!” To be sure, something extraordinary has happened regarding this Hegelian world view. Hardly had Hegel himself departed when his school fell apart. And one could see how this Hegelian school appropriated precisely the form of one of our new parliaments. There was a left wing and a right wing, an extreme left and an extreme right, an ultra-radical wing and an ultra-conservative wing. There were men with radical scientific and social views, who felt themselves to be Hegel's true spiritual heirs, and on the other side there were devout, positive theologians who wanted just as much to base their extreme theological conservatism on Hegel. There was a center for Hegelian studies headed by the amiable philosopher, Karl Rosenkranz, and each of these personalities, every one of them, insisted that he was Hegel's true heir. What is this remarkable phenomenon in the evolution of human knowledge? What happened was that a philosopher once sought to raise humanity into the highest realms of thought. Even if one is opposed to Hegel, it cannot be denied that he dared attempt to call forth the world within the soul in the purest thought-forms. Hegel raised humanity into ethereal heights of thinking, but strangely enough, humanity then fell right back down out of those heights. It drew on the one hand certain materialistic and on the other hand certain positive theological conclusions from Hegel's thought. And even if one considers the Hegelian center headed by the amiable Rosenkranz, even there one cannot find Hegel's philosophy as Hegel himself had conceived it. In Hegel's philosophy one finds a grand attempt to pursue the scientific method right up into the highest heights. Afterward, however, when his followers sought to work through Hegel's thoughts themselves, they found that one could arrive thereby at the most contrary points of view. Now, one can argue about world views in the study, one can argue within the academies, and one can even argue in the academic literature, so long as worthless gossip and Barren cliques do not result. These offspring of Hegelian philosophy, however, cannot be carried out of the lecture halls and the study into life as social impulses. One can argue conceptually about contrary world views, but within life itself these contrary world views do not fight so peaceably. One must use just such a paradoxical expression in describing such a phenomenon. And thus there stands before us in the first half of the nineteenth century an alarming factor in the evolution of human cognition, something that has proved itself to be socially useless in the highest degree. With this in mind we must then raise the question: how can we find a mode of thinking that can be useful in social life? In two phenomena above all we notice the uselessness of Hegelianism for social life. One of those who studied Hegel most intensively, who brought Hegel fully to life within himself, was Karl Marx. And what is it that we find in Marx? A remarkable Hegelianism indeed! Hegel up upon the highest peak of the conceptual world—Hegel upon the highest peak of Idealism—and the faithful student, Karl Marx, immediately transforming the whole into its direct opposite, using what he believed to be Hegel's method to carry Hegel's truths to their logical conclusions. And thereby arises historical materialism, which is to be for the masses the one world view that can enter into social life. We thus are confronted in the first half of the nineteenth century with the great Idealist, Hegel, who lived only in the Spirit, only in his ideas, and in the second half of the nineteenth century with his student, Karl Marx, who contemplated and recognized the reality of matter alone, who saw in everything ideal only ideology. If one but takes up into one's feeling this turnabout of conceptions of world and life in the course of the nineteenth century, one feels with all one's soul the need to achieve an understanding of nature that will serve as a basis for judgments that are socially viable. Now, if we turn on the other hand to consider something that is not so obviously descended from Hegel but can be traced back to Hegel nonetheless, we find still within the first half of the nineteenth century, but carrying over into the second half, the “philosopher of the ego,” Max Stirner. While Karl Marx occupies one of the two poles of human experience mentioned yesterday, the pole of matter upon which he bares all his considerations, Stirner, the philosopher of the ego, proceeds from the opposite pole, that of consciousness. And just as the modern world view, gravitating toward the pole of matter, becomes unable to discover consciousness within that element (as we saw yesterday in the example of du Bois-Reymond), a person who gravitates to the opposite pole of consciousness will not be able to find the material world. And so it is with Max Stirner. For Max Stirner, no material universe with natural laws actually exists. Stirner sees the world as populated solely by human egos, by human consciousnesses that want only to indulge themselves to the full. “I have built my thing on nothing”—that is one of Max Stirner's maxims. And on these grounds Stirner opposes even the notion of Providence. He says for example: certain moralists demand that we should not perform any deed out of egoism, but rather that we should perform it because it is pleasing to God. In acting, we should look to God, to that which pleases Him, that which He commands. Why, thinks Max Stirner, should I, who have built only upon the foundation of ego-consciousness, have to admit that God is after all the greater egoist Who can demand of man and the world that all should be performed as it suits Him? I will not surrender my own egoism for the sake of a greater egoism. I will do what pleases me. What do I care for a God when I have myself? One thus becomes entangled and confused within a consciousness out of which one can no longer find the way. Yesterday I remarked how on the one hand we can arrive at clear ideas by awakening in the experience of ideas when we descend into our consciousness. These dreamlike ideas manifest themselves like drives from which we cannot then escape. One would say that Karl Marx achieved clear ideas—if anything his ideas are too clear. That was the secret of his success. Despite their complexity, Marx's ideas are so clear that, if properly garnished, they remain comprehensible to the widest circles. Here clarity has been the means to popularity. And until it realizes that within such a clarity humanity is lost, humanity, as long as it seeks logical consequences, will not let go of these clear ideas. If one is inclined by temperament to the other extreme, to the pole of consciousness, one passes over onto Stirner's side of the scale. Then one despises this clarity: one feels that, applied to social thinking, this clarity makes man into a cog in a social order modeled on mathematics or mechanics—but into that only, into a mere cog. And if one does not feel oneself cut out for just that, then the will that is active in the depths of human consciousness revolts. Then one comes radically to oppose all clarity. One mocks all clarity, as Stirner did. One says to oneself: what do I care about anything else? What do I care even about nature? I shall project my own ego out of myself and see what happens. We shall see that the appearance of such extremes in the nineteenth century is in the highest degree characteristic of the whole of recent human evolution, for these extremes are the distant thunder that preceded the storm of social chaos we are now experiencing. One must understand this connection if one wants at all to speak about cognition today. Yesterday we arrived at an indication of what happens when we begin to correlate our consciousness to an external natural world of the senses. Our consciousness awakens to clear concepts but loses itself. It loses itself to the extent that one can only posit empty concepts such as “matter,” concepts that then become enigmatic. Only by thus losing ourselves, however, can we achieve the clear conceptual thinking we need to become fully human. In a certain sense we must first lose ourselves in order to find ourselves again out of ourselves. Yet now the time has come when we should learn something from these phenomena. And what can one learn from these phenomena? One can learn that, although clarity of conceptual thinking and perspicuity of mental representation can be won by man in his interaction with the world of sense, this clarity of conceptual thinking becomes useless the moment we strive scientifically for something more than a mere empiricism. It becomes useless the moment we try to proceed toward the kind of phenomenalism that Goethe the scientist cultivated, the moment we want something more than natural science, namely Goetheanism. What does this imply? In establishing a correlation between our inner life and the external physical world of the senses we can use the concepts we form in interaction with nature in such a way that we try not to remain within the natural phenomena but to think on beyond them. We are doing this if we do more than simply say: within the spectrum there appears the color yellow next to the color green, and on the other side the blues. We are doing this if we do not simply interrelate the phenomena with the help of our concepts but seek instead, as it were, to pierce the veil of the senses and construct something more behind it with the aid of our concepts. We are doing this if we say: out of the clear concepts I have achieved I shall construct atoms, molecules—all the movements of matter that are supposed to ex-ist behind natural phenomena. Thereby something extraordinary happens. What happens is that when I as a human being confront the world of nature [see illustration], I use my concepts not only to create for myself a conceptual order within the realm of the senses but also to break through the boundary of sense and construct behind it atoms and the like I cannot bring my lucid thinking to a halt within the realm of the senses. I take my lesson from inert matter, which continues to roll on even when the propulsive force has ceased. My knowledge reaches the world of sense, and I remain inert. I have a certain inertia, and I roll with my concepts on beyond the realm of the senses to construct there a world the existence of which I can begin to doubt when I notice that my thinking has only been borne along by inertia.  It is interesting to note that a great proportion of the philosophy that does not remain within phenomena is actually nothing other than just such an inert rolling-on beyond what really exists within the world. One simply cannot come to a halt. One wants to think ever farther and farther beyond and construct atoms and molecules—under certain circumstances other things as well that philosophers have assembled there. No wonder, then, that this web one has woven in a world created by the inertia of thinking must eventually unravel itself again. Goethe rebelled against this law of inertia. He did not want to roll onward thus with his thinking but rather to come strictly to a halt at this limit [see illustration: heavy line] and to apply concepts within the realm of the senses. He thus would say to himself: within the spectrum appear to me yellow, blue, red, indigo, violet. If, however, I permeate these appearances of color with my world of concepts while remaining within the phenomena, then the phenomena order themselves of their own accord, and the phenomenon of the spectrum teaches me that when the darker colors or anything dark is placed behind the lighter colors or anything light, there appear the colors which lie toward the blue end of the spectrum. And conversely, if I place light behind dark, there appear the colors which lie toward the red end of the spectrum. What was it that Goethe was actually seeking to do? Goethe wanted to find simple phenomena within the complex but above all such phenomena as allowed him to remain within this limit [see illustration], by means of which he did not roll on into a realm that one reaches only through a certain mental inertia. Goethe wanted to adhere to a strict phenomenalism. If we remain within phenomena and if we strive with our thinking to come to a halt there rather than allow ourselves to be carried onward by inertia, the old question arises in a new way. What meaning does the phenomenal world have when I consider it thus? What is the meaning of the mechanics and mathematics, of the number, weight, measure, or temporal relation that I import into this world? What is the meaning of this? You know, perhaps, that the modern world conception has sought to characterize the phenomena of tone, color, warmth, etc. as only subjective, whereas it characterizes the so-called primary qualities, the qualities of weight, space, and time, as something not subjective but objective and inherent in things. This conception can be traced back principally to the English philosopher, John Locke, and it has to a considerable extent determined the philosophical basis of modern scientific thought. But the real question is: what place within our systematic science of nature as a whole do mathematics, do mechanics—these webs we weave within ourselves, or so it seems at first—what place do these occupy? We shall have to return to this question to consider the specific form it takes in Kantianism. Yet without going into the whole history of this development one can nonetheless emphasize our instinctive conviction that measuring or counting or weighing external objects is essentially different from ascribing to them any other qualities. It certainly cannot be denied that light, tones, colors, and sensations of taste are related to us differently from that which we could represent as subject to mathematical-mechanical laws. For it really is a remarkable fact,a fact worthy of our consideration: you know that honey tastes sweet, but to a man with jaundice it tastes bitter—so we can say that we stand in a curious relationship to the qualities within this realm—while on the other hand we could hardly maintain that any normal man would see a triangle as a triangle, but a man with jaundice would see it as a square! Certain differentiations thus do exist, and one must be cognizant of them; on the other hand, one must not draw absurd conclusions from them. And to this very day philosophical thinking has failed in the most extraordinary way to come to grips with this most fundamental epistemological question. We thus see how a contemporary philosopher, Koppelmann, overtrumps even Kant by saying, for example—you can read this on page 33 of his Philosophical Inquiries [Weltanschauungsfragen]: everything that relates to space and time we must first construct within by means of the understanding, whereas we are able to assimilate colors and tastes directly. We construct the icosahedron, the dodecahedron, etc.: we are able to construct the standard regular solids only because of the organization of our understanding. No wonder, then, claims Koppelmann, that we find in the world only those regular solids we can construct with our understanding. One thus can find Koppelmann saying almost literally that it is impossible for a geologist to come to a geometer with a crystal bounded by seven equilateral triangles precisely because—so Koppelmann claims—such a crystal would have a form that simply would not fit into our heads. That is out-Kanting Kant. And thus he would say that in the realm of the thing-in-itself crystals could exist that are bounded by seven regular triangles, but they cannot enter our head, and thus we pass them by; they do not exist for us. Such thinkers forget but one thing: they forget—and it is just this that we want to indicate in the course of these lectures with all the forceful proofs we can muster—that the natural order governing the construction of our head also governs the construction of the regular polyhedrons, and it is for just this reason that our head constructs no other polyhedrons than those that actually confront us in the external world. For that, you see, is one of the basic differences between the so-called subjective qualities of tone, color, warmth, as well as the different qualities of touch, and that which confronts us in the mechanical-mathematical view of the world. That is the basic difference: tone and color leave us outside of ourselves; we must first take them in; we must first perceive them. As human beings we stand outside tone, color, warmth, etc. This is not entirely the case as regards warmth—I shall discuss that tomorrow—but to a certain extent this is true even of warmth. These qualities leave us initially outside ourselves, and we must perceive them. In formal, spatial, and temporal relationships and regarding weight this is not the case. We perceive objects in space but stand ourselves within the same space and the same lawfulness as the objects external to us. We stand within time just as do the external objects. Our physical existence begins and ends at a definite point in time. We stand within space and time in such a way that these things permeate us without our first perceiving them. The other things we must first perceive. Regarding weight, well, ladies and gentlemen, you will readily admit that this has little to do with perception, which is somewhat open to arbitrariness: otherwise many people who attain an undesired corpulence would be able to avoid this by perception alone, merely by having the faculty of perception. No, ladies and gentlemen, regarding weight we are bound up with the world entirely objectively, and the organization by means of which we stand within color, tone, warmth, etc. is powerless against that objectivity. So now we must above all pose the question: how is it that we arrive at any mathematical-mechanical judgment? How do we arrive at a science of mathematics, at a science of mechanics? How is it, then, that this mathematics, this mechanics, is applicable to the external world of nature, and how is it that there is a difference between the mathematical-mechanical qualities of external objects and those that confront us as the so-called subjective qualities of sensation, tone, color, warmth, etc.? At the one extreme, then, we are confronted with this fundamental question. Tomorrow we shall discuss another such question. Then we shall have two starting-points from which we can proceed to investigate the nature of science. Thence we shall proceed to the other extreme to investigate the formation of social judgments. |

| 70b. Ways to a Knowledge of the Eternal Forces of the Human Soul: The World View Of German Idealism. A Consideration Regarding Our Fateful Times

25 Nov 1915, Stuttgart Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| He who stands as it were as the first cornerstone of this newer Central European, this newer spiritual world-view development is much misunderstood: Kant. It often seems to people as if Kant had wanted to put forward a world-view of doubt, a world-view of uncertainty. |

| The most alien thing to the times in which Kant lived and the culture from which Kant emerged would be the British view of today, as expressed in the British world view: that truth should have no other source [than the expediency for which external phenomena are to be summarized]. |

| From the individual spirit, from the individual ego, Hegel wants to go to the world spirit, which is connected at one point with the individual spirit of man. |

| 70b. Ways to a Knowledge of the Eternal Forces of the Human Soul: The World View Of German Idealism. A Consideration Regarding Our Fateful Times

25 Nov 1915, Stuttgart Rudolf Steiner |

|---|