| 301. The Renewal of Education: Synthesis and Analysis in Human Nature and Education

05 May 1920, Basel Translated by Ruth Pusch, Gertrude Teutsch Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| 301. The Renewal of Education: Synthesis and Analysis in Human Nature and Education

05 May 1920, Basel Translated by Ruth Pusch, Gertrude Teutsch Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

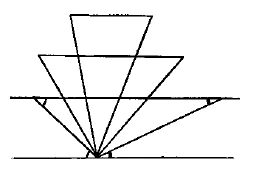

You have seen how spiritual science works toward using educational material as a means for raising children. The scientific forms of the instructional material are presented to the child in such a way that those forces within the child that prepare him or her for development are drawn out. If we are to work fruitfully with the instructional material we have, we need to pay attention to the course of activity of the child’s soul. If we look at the activity of a human soul, we see two things. The first is a tendency toward analysis and the second is a tendency toward synthesis. Everyone knows from logic or psychology what the essential nature of analysis and synthesis is. But it is important to comprehend these things not simply in their abstract form, as they are normally understood, but in a living way. We can recall what analysis is if we say to ourselves the following: if we have ten numbers or ten things, then we can imagine these ten things by imagining three, five, and two, and adding to it the idea that ten can be divided, or analyzed as three, five, and two. When working with synthesis, our concern is just the opposite: we simply add three, five, and two. As I said, in an objective, abstract, and isolated sense, everyone knows what analysis and synthesis are. But when we want to comprehend the life of the human soul, we find that the soul is continuously impelled to form syntheses. For example, we look at an individual animal out of a group of animals and we form a general concept, that of the species. In that case, we summarize, that is, we synthesize. Analysis is something that lies much deeper, almost in the unconscious. This is a desire to make multiplicity out of unity. Since this has been little taken into account, people have understood little of what human freedom represents in the soul. If the activity of the human soul were solely synthetic—that is, if human beings were connected with the external world in such a way that they could onlysynthesize, they could only form concepts of species and so forth—we could hardly speak of human freedom. Everything would be determined by external nature. In contrast, the soul aspect of all of our deeds is based upon analysis, which enables us to develop freedom in the life of pure thinking. If I am to find the sum of two and five and three, I have no freedom. There is a rule that dictates how much two and five and three are. On the other hand, if I have ten, then I can represent this number ten as nine plus one, or five plus five or three plus five plus two, and so forth. When analyzing, I carry out a completely free inner activity. When synthesizing, I am required by the external world to unfold the life in my soul in a particular way. In practical life, we analyze when, for example, we take a particular position and say we want to consider one thing or another from this perspective. In this case, we dissect everything we know about the thing into two parts. We analyze and separate everything and then put ourselves in a certain position. For instance, I could consider getting up early purely from the standpoint of, say, a greater inclination to do my work in the early morning. I could also consider getting up early from other perspectives. I might even go so far in my analysis that I have two or three perspectives. In this analytical activity in my soul, I am in a certain way free. Since we develop this analytical soul activity continuously and more or less unconsciously, we are free human beings. No one can overcome the difficulties in the question of human freedom who does not understand this analytical tendency in human beings. And yet it is just this analytical activity that is normally taken too little into account in teaching and education. We are more likely to take the view that the external world demands synthesis. Consequently synthesizing is what is primarily taken into account rather than analyzing. This is very significant. If, for example, you want to pursue the idea of beginning with dialect when teaching language, it is clear how necessary it is to analyze. The child already has a dialect language. When we have the child speak some sentences, we then need to analyze what already exists in those sentences in order to derive the rules of speech formation from them. We can also develop the analytical activity in instruction much further. I would like to draw your attention to something that you have probably already encountered in one form or another. What I am referring to is how, for example, when explaining letters we are not primarily involved in a synthetic but rather in an analytic activity. If I have a child say the word fish and then simply write the word on the blackboard, I attempt to teach the child the word without dividing it into separate letters. I might even attempt to have the child copy the word, assuming he or she has been drawing in the way I discussed previously. Of course the child has at this time no idea that there is an f-i-s-h within it. The child should simply imitate what I put on the board. Before I go on to the letters, I would often try to have the child copy complete words.Now I go on to the analysis. I would try to draw the child’s attention to how the word begins with f. Thus, I analyze the f in the context of the word. I then do the same with the i and so forth. Thus we work with human nature as it is when, instead of beginning with letters and synthesizing them into words, we begin with whole words and analyze them into letters. This is something we also need to take into account, particularly from the perspective of the development of the human soul in preparation for later life. As you all know, we suffer today under the materialistic view of the world. This perspective demands not only that we only accept material things as being valid. It also insists that we trace everything in the world back to the activities of atoms. It is unimportant whether we think of those atoms in the way people thought of them in the 1880s, that is, as small elastic particles made up of some unknown material, or whether we think of them as people do today—as electrical forces or electrical centers of force. What is important in materialism is material itself, and when the tools of materialism are transferred to our view of the spirit and soul, we think of them as being composed of tiny particles and depending upon the activities of those particles. Today we have come so far that we are no longer aware that we are working with hypotheses. Most people believe it is a proven scientific fact that atoms form the basis of phenomena in the external world. Why have people in our age developed such an inclination for atomism? Because they have developed insufficient analytical activities in children. If we were to develop in children those analytical activities that begin with unified word pictures and then analyze them into letters, the child would be able to activate its capacity to analyze at the age when it first wants to do so; it would not have to do so later by inventing atomic structures and so forth. Materialism is encouraged by a failure to satisfy our desire for analysis. If we satisfied the impulse to analyze in the way that I have described here, we would certainly keep people from sympathizing with the materialistic worldview. For this reason in the Waldorf School we always teach beginning not with letters, but with complete sentences. We analyze the sentence into words and the words into letters and then the letters into vowels. In this way we come to a proper inner understanding as the child grasps the meaning of what a sentence or word is. We awaken the child’s consciousness by analyzing sentences and words. When you accept a child as he is and see how he speaks a dialect, then it is not at all necessary to begin with the opposite method. Children understand the unity of sentences much more than we think. Children whose tendency to analyze is accepted develop a greater awareness than is generally the case in today’s population. We have sinned a great deal in education in regard to the awareness in people’s souls. We could actually say that we sleep not only in the time between falling asleep and awakening, nor are we simply awake during the period from awakening until falling asleep. To some extent during daily life we alternate continually between being awake and being asleep. The activity of inhaling and exhaling is at the same time an illumination and a darkening, though we may not notice it. We do not notice it because it occurs quite quickly and because the darkening and illumination are very weak. The rapidity of the process and the subtlety of the changes make this imperceptible. Nevertheless it is true that with every inhalation we go to sleep in a certain sense, and when we exhale, in a certain sense we awaken. In this sense wakefulness and sleeping continually alternate within us. This is also true of the mind. As a rule, with every analytical activity we awaken, and with every synthesizing activity we fall asleep. Of course this does not mean the ordinary states we are in during the night or day. Even so there is a relationship between analyzing and awakening and synthesizing and falling asleep. We therefore develop a tendency in the child to confront the world with a wakeful soul when we use the child’s desire to analyze, when we develop the individual details from unified things. This is something we must particularly take into account in teaching arithmetic. We often do not sufficiently consider the relationship of arithmetic to the child’s soul life. First of all we must differentiate between arithmetic and simple counting. Many people think counting represents a kind of addition, but that is not so. Counting is simply naming differing quantities. Of course, counting needs to precede arithmetic, at least counting up to a certain number. We certainly need to teach children how to count. But we must also use arithmetic to properly value those analytical forces that want to be developed in the child’s soul. In the beginning, we need to attempt, for instance, to begin with the number ten and then divide it in various ways. We need to show the children how ten can be separated into five and five, or into three and three and three and one. We can achieve an enormous amount in supporting what human nature actually strives for out of its inner forces when we do not teach addition by saying that the addends are on the left and the sum is on the right, but by saying that we have the sum on the left and the addends on the right. We should begin with analyzing the sum and then work backwards toward addition. If you wish, you can take this presentation as a daring statement. Nevertheless those who have achieved an unprejudiced view of the forces within human nature will recognize that when we place the sum on the left and the addends on the right, and then teach the child how to separate the sum in any number of ways, we support the child’s desire to analyze. Only afterward do we work with those desires that actually do not play a role within the soul, but instead are important with interactions of people within the external world. What a child analyzes out of a unity exists essentially only for herself. What is synthesized exists always for external human nature. Now you might say that what I had said previously regarding the concept of species, for example, is the result ofsyntheses. And that is true. However, we cannot understand the process of synthesizing as simply the creation of abstract concepts. Certainly people believe that when we form general concepts such as wolfor lamb, these are general concepts that develop only in our reasoning.This, however, is not the case. The things that exist outside of all substance, and which we comprehend in the idea of a wolf or lamb, are also real. If they were not real, if only material substance were real, then if we were to cage a wolf and feed it only lamb, after a period of time it would have to become like a lamb. Clearly this is something that will not happen because a wolf is something more than simply the matter out of which it is made. The additional aspect of which a wolf consists becomes clear to us through the concept that we form through synthesis. It is certainly also something that corresponds to an external reality. On the other hand, what we in the end separate out of something into various parts corresponds to something subjective in many cases, but particularly in those cases where our concern is to find a point of view. It is certainly a subjective activity when I separate the sum on the left into the addends so that I have the addends on the right. In that case, I have what needs to be on the right. If I have the sum on the left and then separate it into parts, then I can do the separation from various points of view and thus the addends can take on numerous forms. It is very important to develop this freedom of will in children. Similarly, in multiplication we should not attempt to begin with the factors and proceed to the product. Instead we should begin with the product and form the factors in many various ways. Only afterwards should we turn to the synthesizing activity. This way through arithmetic people may be able to develop the rhythmic activity within the life of the soul that consists of analyzing and synthesizing. In the way we teach arithmetic today, we often emphasize one side too strongly. For the soul, such overemphasis has the same effect as if we wereto heap breath upon breath upon the body and not allow it to exhale in the proper way. It is important to take the individuality of the human being into account in the proper way. This is what I mean when I speak of the fructification that education can experience through spiritual science. We need to become aware of what actually wants to develop out of the child’s individuality. First we need to know what can be drawn out of the child. At the outset children have a desire to be satisfied analytically; then they want to bring that analysis together through synthesis. We must take these things into account by looking at human nature. Otherwise even the best pedagogical principles—although they may be satisfying to use and we believe they are fulfilling all that is required—will never be genuinely useful because we do not actually try to look at the results of education in life. People are curiously short-sighted in their judgment. If you had lived during the 1870s, as I did, you would have heard in Prussia (and also from some people in Austria) that Prussia won the war with Austria in 1866 because the Austrian schools at an earlier time were worse than those in Prussia. It was actually the Prussian teachers who won. Since October 1918 I have not heard similar talk in Germany, although there would perhaps be reason to speak that way. But of course the talk in Germany would have to be the other way around. We can learn from such things. They show how people have too strong a tendency to form judgments not according to the facts, but according to their sympathies and antipathies, according to what they feel. This is because there are many things in human nature that are not developed, but actually demand to be developed as human forces. We will, however, always find our way if we take the rhythmic needs within the whole human being into account. We do that when we do not simply teach addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. When teaching addition, we should not simply expect answers to the question of what is the sum of so and so much. Instead we should expect answers to the question of how a sum can be separated in various ways. In contrast, the question with regard to subtraction is, from what number do we need to remove five in order to have the result be eight? In general, we need to pose all these kinds of questions in the opposite way to which they are posed in synthetic thinking when interacting with external world. Here we can place the teaching of arithmetic in parallel with teaching language, where we begin with the whole and then go on to the individual letters. In our Waldorf School it is very pleasing to see the efforts the children make when they take a complete word and try to find out how it sounds, how we pronounce it, what is in the middle, and so forth, and in that way go on to the individual letters. When we atomize or analyze in this way, children will certainly not have any inclination toward materialism or atomism such as everyone does today, because modern people have been taught only synthetic thinking in school and thus their need to be analytical, their need to separate, can only develop in their worldviews. We must, however, take something else into account. Human nature, as I mentioned yesterday, basically begins with activity and only then goes on to rest. Just as a baby begins by kicking and waving its arms and then becomes quiet, the entirety of human nature begins with activity and must learn how to come to rest. This process actually needs to be developed quite systematically. Thus what is important is that we, in a sense, educate people based upon their own movement. It is very easy to make an error in that regard today. I have already tried to show how important it is at the beginning of elementary school to work with the musical and singing elements. We need to work with the child’s musical needs as much as possible. Today, however, it would be very easy for an erroneous prejudice against these ideasto arise. If we look at the modern world—and most of you will have already noticed this—there are nearly as many methods of teaching singing as there are singing teachers. Of course each one always believes his or her own method is the best. If we simply apply these methods of teaching singing and music to adults, who are already beyond the age of development, we can allow them to pick and choose the method they want. Essentially all such methods begin with an erroneous position. They assume that we need to quiet the human organs in order to develop the activity that is desired. Thus, in a sense, the activity of the lungs, for example, must be quieted in order to develop that activity in the lungs which in this case, in singing, should predominate. However, just the opposite occurs within human nature. Nearly all methods of teaching singing that I have every seen actually begin with our modern materialism. They begin with the assumption that the human being is somehow mechanical and needs to be quieted in order to be able to develop the necessary activity. This assumption is something that can never be important when we genuinely see the nature of the human being. The proper method of teaching singing or developing a musical ear assumes that children normally hear properly,and then a desire develops within the child to imitate so that the imitation adjusts to that hearing. Thus the best method is for the teacher to sing to the children with a certain kind of love and to adjust to what is missing in them musically. In that way, the natural need of the students to imitate and have their mistakes corrected is awakened though what they hear from the teacher. However, in singing, children need to learn what instinctively results from quieting the organs. In the same way, speaking serves to regulate the human breathing rhythm. In school we need to work so that the children learn how to bring their speech into a peaceful regularity. We need to require that the children speak syllable for syllable, that they speak slowly and that they properly form the syllables so that nothing of the word is left out. The children need to grow accustomed to proper speech and verse, to well-formed speech, and develop a feeling rather than a conscious understanding of the rise and fall of the tones in verses. We need to speak to the children in the proper way so that they learn to hear. During childhood the larynx and neighboring organs adjust to the hearing. As I said, the methods common today may be appropriate for adults, as what results from those methods will be included or not included in one way or another by life itself. In school, however, we need to eliminate all such artificial methods. Here what is most needed is the natural relationship of the teacher to the student. The loving devotion of the child to the teacher should replace artificial methods. I would, in fact, say that intangible effects should be the basis of our work. Nothing would be more detrimental than if all the old aunts and uncles with their teaparty ideas of music and methods were to find their way into school. In school what should prevail is the spirit of the subject. But that can only occur when you, the teacher, are enveloped by the subject, not when you want to teach the subject to the children through external methods. If in the school education becomes more of an art such as we have been discussing, then I believe people will be less inclined to learn things according to some specific method than they are today. If children at the age of six or seven are taught music and singing in a natural way, later on they will hardly take any interest in the outrageous methods that play such a large role in modern society. In my opinion, modern education should also require the teacher to look objectively at everything in the artificiality of our age, and eliminate it through instruction during elementary school. There are many things—such as the methods I just mentioned—that are very difficult to overcome. The people who use such methods are fanatical and can see only how their methods may reform the world. In general, it is useless to try to discuss such things reasonably and objectively with these people. Such things can only be brought into their proper context by the next generation. Here is where we can make an impact. In regard to society it is always the next generation that accomplishes a great deal. The art of teaching and education consists not only of the methods used, but also of the perspective that results from the teacher’s interest in the general development of humanity. Teachers need to have a comprehensive interest in the development of humanity, and they need to have an interest in everything that occurs during the present time. The last thing a teacher should do is to limit his or her interests. The interests we develop for the cultural impulses of our age have an enlivening effect upon our entire attitude and bearing as teachers. You will excuse me when I say that much of what is properly felt to be pedantic in schools would certainly go away if the faculty were interested in the major events of life and if they would participate in public activities. Of course, people don’t like to see this, particularly in reactionary areas, but it is important for education not to simply have a superficial interest. A question was asked of me today that is connected with what I have just said. I was asked what the direction of language is, what we should do so that all of the words that have lost their meaning no longer form a hindrance to the development of thinking, so that a new spiritual life can arise. An English mathematician who attempted to form a mathematical description of all the ways of thinking recently said, in a lecture he gave on education, that style is the intellectual ethical aspect. I think this could be a genuine literary ideal. In order to speak or write ethically each person would need a particular vocabulary for himself, just as each people does now. In language as it is now, the art of drama only develops the words, but seldom develops general human concepts. How can we transform language so that in the future the individual thought or feeling, as well as the generality of the individual concept, becomes audible or visible? Or should language simply disappear and be replaced by something else in the future? Now that is certainly quite a collection of questions! Nevertheless I want to go into them a little today; tomorrow and the next day I will speak about them in more detail. It is necessary to look into how more external relationships to language exist in our civilized languages, since they are in a certain way more advanced than external relationships that exist in other languages. There is, for example, something very external in translation by taking some text in one language and looking up the words in a dictionary. When working this way you will in general not achieve what exists in the language beyond anything purely external. Language is not simply permeated by reason; it is directly experienced, directly felt. For that reason, people would become terribly externalized if everyone were to speak some general language like Esperanto. I am not prejudiced; I have heard wonderful-sounding poems in Esperanto. But much of what lives in a language in regard to the feelings, the life of the language, would be lost through such a universal language. This is also something that is always lost when we simply translate one language word for word into another using a dictionary. We therefore need to say that in one sense the man who spoke about that here was quite correct, although it is not good to make such things into formulas. It is not good to try to formulate thoughts mathematically or to do other things that are only of interest in the moment. What we can say, though, is that it is important for us to try to imbue our language with spirit. Our language, like all civilized languages, has moved strongly into clichés. For that reason, it is particularly good to work with dialect. Dialects, where they are spoken, are more alive than so-called standard language. A dialect contains much more personal qualities: it contains secret, intimate qualities. People who speak in dialect speak more accurately than those who speak standard language. In dialect, it is more difficult to lie than it is in standard language. That assertion may appear paradoxical to you, but it is nevertheless true in a certain sense. Of course I am not saying there are no bald-faced liars who speak dialect. But it is true that such people must be much worse than they would need to be if they were to lie only in educated, standard language. There you do not need to be as bad in order to lie, because the language itself enables lying more than when you speak in dialect. You need to be a really bad person if you are to lie in dialect because people love the words in dialect more than they do those of standard language. People are ashamed to use words in dialect as clichés, whereas the words in standard language can easily be used as clichés. This is something that we need to teach people in general—that there are genuine experiences in the words. Then we need to bring life into the language as well. Today hardly anyone is interested in trying to bring life into language. I have tried to do that in my books in homeopathic doses. In order to make certain things understandable, I have used in my books a concept that has the same relationship to force as water flowing in a stream does to the ice on top of the stream. I used the word kraften (to work actively, forcefully). Usually we only have the word Kraft, meaning “power” or “force.” We do not speak of kraften. We can also use similar words. If we are to bring life into language, then we also need a syntax that is alive, not dead. Today people correct you immediately if you put the subject somewhere in the sentence other than where people are accustomed to having it. Such things are still just possible in German, and you still have a certain amount of freedom. In the Western European languages—well, that is just terrible, everything is wrong there. You hear all the time that you can’t say that, that is not English, or that is not French. But, to say “that is not German” is not possible. In German you can put the subject anywhere in the sentence. You can also give an inner life to the sentence in some way. I do not want to speak in popular terms, but I do want to emphasize the process of dying in the language. A language begins to die when you are always hearing that you cannot say something in one way or another, that you are speaking incorrectly. It may not seem as strange but it is just the same as if a hundred people were to go to a door and I were to look at them and decide purely according to my own views who was a good person and who was a bad person. Life does not allow us to stereotype things. When we do that, it appears grotesque. Life requires that everything remain in movement. For that reason, syntax and grammar must arise out of the life of feeling, not out of dead reasoning. That perspective will enable us to continue with a living development of language. Goethe introduced much dialect into language. It is always good to enliven written language with dialect because it enables words to be felt in a warmer, more lively way. We should also consider that a kind of ethical life is brought into language. (This, of course, does not mean that we should be humorless in our speech. Friedrich Theodore Vischer2 wrote a wonderful book about the difference between frivolity and cynicism. It also contains a number of remarks about language usage and about how to live into language.) When teaching language, we have a certain responsibility to use it also as a training for ethics in life. Nevertheless there needs to be some feeling; it should not be done simply according to convention. We move further and further away from what is alive in language if we say, as is done in the Western European languages, that one or another turn of phrase is incorrect and that only one particular way of saying things is allowed. |

| 301. The Renewal of Education: Rhythm in Education

06 May 1920, Basel Translated by Ruth Pusch, Gertrude Teutsch Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| 301. The Renewal of Education: Rhythm in Education

06 May 1920, Basel Translated by Ruth Pusch, Gertrude Teutsch Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

If we look again at the three most important phases of elementary school, then we see that they are: first, from entering elementary school at about the age of six or seven until the age of nine; then second, from the age of nine until about the age of twelve; and finally from twelve until puberty. The capacity to reason independently only begins to occur when people have reached sexual maturity, even though a kind of preparation for this capacity begins around the age of twelve. For this reason, the third phase of elementary school begins about the age of twelve. Every time a new phase occurs in the course of human life, something is born out of human nature. I have previously noted how the same forces—which become apparent as the capacity to remember, the capacity to have memories, and so forth—that appear at about the age of seven have previously worked upon the human organism up until that age. The most obvious expression of that working is the appearance of the second set of teeth. In a certain sense, forces are active in the organism that later become important during elementary school as the capacity to form thoughts. They are active but hidden. Later they are freed and become independent. The forces that become independent we call the forces of the etheric body. Once again at puberty other forces become independent which guide us into the external world in numerous ways. Hidden within that system of forces is also the capacity for independent reasoning. We can therefore say that the actual medium of the human capacity for reason, the forces within the human being that give rise to reasoning, are basically born only at the time of puberty, and have slowly been prepared for that birth beginning at the age of twelve. When we know this and can properly honor it, then we also become aware of the responsibility we take upon ourselves if we accustom people to forming independent judgments too soon. The most damaging prejudices in this regard prevail at the present time. People want to accustom children to forming independent judgments as early as possible. I previously said that we should relate to children until puberty in such a way that they recognize us as an authority, that they accept something because someone standing next to them who is visibly an authority requests it and wants it. If we accustom children to accepting the truth simply because we as authorities present it to them, we will prepare them properly for having free and independent reasoning later in life. If we do not want to serve as an authority figure for the child and instead try to disappear so that everything has to develop out of the child’s own nature, we are demanding a capacity for reason too early, before what we call the astral body becomes free and independent at puberty. We would be working with the astral body by allowing it to act upon the physical nature of the child. In that way we will impress upon the child’s physical body what we should actually only provide for his soul. We are preparing something that will continue to have a damaging effect throughout the child’s life. There is quite a difference between maturing to free judgment at the age of fourteen or fifteen—when the astral body, which is the carrier of reasoning, has become free after a solid preparation—than if we have been trained in so-called independent judgment at too early an age. In the latter case, it is not our astral aspect, that is, our soul, which is brought into independent reasoning, but our physical body instead. The physical body is drawn in with all its natural characteristics, with its temperament, its blood characteristics, and everything that gives rise to sympathy and antipathy within it, with everything that provides it with no objectivity. In other words, if a child between the ages of seven and fourteen is supposed to reason independently, the child reasons out of that part of human nature which we later can no longer rid ourselves of if we are not careful to see that it is cared for in a natural way, namely, through authority, during the elementary school period. If we allow children to reason too early, it will be the physical body that reasons throughout life. We then remain unsteady in our reasoning, as it depends upon our temperament and all kinds of other things in the physical body. If we are prepared in a way appropriate to the physical body and in a way that the nature of the physical body requires—that is, if we are brought up during the proper time under the influence of authority—then the part of us that should reason becomes free in the proper way and later in life we will be able to achieve objective judgment. Therefore the best way to prepare someone to become a free and independent human being is to avoid guiding the child toward freedom at too early an age. This can cause a great deal of harm if it is not used properly in education. In our time it is very difficult to become sufficiently aware of this. If you talk about this subject with people today who are totally unprepared and who have no good will in this regard, you will find yourself simply preaching to deaf ears. Today we live much more than we believe in a period of materialism, and it is this age of materialism that needs to be precisely recognized by teachers. They need to be very aware of how much materialism is boiling up within modern culture and modern attitudes. I would now like to describe this matter from a very different perspective. Something remarkable happened in European civilization around 1850, although it was barely noticed: a direct and basic feeling for rhythm was to a very large extent lost. Hence we now have people a few generations later who have entirely lost this feeling for rhythm. Such people are completely unaware of what this lack of rhythm means in raising children. In order to understand this, we need to consider the following. In life people alternate between sleeping and being awake. People think they understand the state called wakefulness because they are aware of themselves. During this time, through sense impressions they gain an awareness of the external world. But they do not know the state between falling asleep and awakening. In modern life, people have no awareness of themselves then. They have few, if any, direct conscious perceptions of the external world. This is therefore a state in which life moves into something like a state of unconsciousness. We can easily gain a picture of the inner connections between these two states only when we recognize two polar opposites in human life that have great significance for education. I am referring here to drawing and music, two opposites I have already mentioned and which I would like to consider from a special point of view again today. Let us first look at drawing, in which I also include painting and sculpting. While doing so, let us recall everything in regard to drawing that we consider to be important to the child from the beginning of elementary school. Drawing shows us that, out of his or her own nature, the human being creates a form we find reflected in the external world. I have already mentioned that it is not so important to hold ourselves strictly to the model. Instead we need to find a feeling for form within our own nature. In the end, we will recognize that we exist in an element that surrounds us during our state of wakefulness in the external world, in everything that we do forming spatially. We draw lines. We paint colors. We sculpt shapes. Lines present themselves to us, although they do not exist in nature as such. Nevertheless they present themselves to us through nature, and the same is true of colors and forms. Let us look at the other element, which we can call musical, that also permeates speech. Here we must admit that in what is musical we have an expression of the human soul. Like sculpting and drawing, everything that is expressed through music has a very rudimentary analogy to external nature. It is not possible to simply imitate with music that which occurs naturally in the external world, just as it is not possible, in a time where a feeling for sculpting or drawing is so weak, to simply imitate the external world. We must ask ourselves then if music has no content. Music does have its own content. The content of music is primarily its melodic element. Melodies need to come to us. When many people today place little value upon the melodic element, it is nothing more than a characteristic of our materialistic age. Melodies simply do not come to people often enough. We can well compare the melodic element with the sculptural element. It is certainly true that the sculptural element is related to space. In the same way the melodic element is related to time. Those who have a lively feeling for this relationship will realize that the melodic element contains a kind of sculpting. In a certain way, the melodic element corresponds to what sculpting is in the external world. Let us now look at something else. You are all acquainted with that flighty element in the life of our souls that becomes apparent in dreams. If we concern ourselves objectively with that element of dreaming, we slowly achieve a different view of dreams than the ordinary one. The common view of dreams focuses upon the content of the dream, which is what commonly interests most people. But as soon as we concern ourselves objectively with this wonderful and mysterious world of dreams, the situation becomes different. Someone might talk about the following dream.

A third or a fourth person could tell still other stories. The pictures are quite different. One person dreams about climbing a mountain, another about going into a cave, and a third about still something else. It is not the pictures that are important. The pictures are simply woven into the dream. What is important is that the person experiences a kind of tension into which they fall when they are unable to solve something that can first be solved upon awakening. It is this moving into a state of tension, the occurrence of the tension, of becoming tense that is expressed in the various pictures. What is important is that human beings in dreams experience increasing and decreasing tension, resolution, expectations, and disappointments, in short, that they experience inner states of the soul that are then expressed in widely differing pictures. The pictures are similar in their qualities of increase and decrease. It is the state of the soul that is important, since these experiences are connected to the general state of the soul. It is totally irrelevant whether a person experiences one picture or another during the night. It is not unimportant, however, whether one experiences a tension and then its resolution or first an expectation and then a disappointment, since the person’s state of mind on the next day depends upon it. It is also possible to experience a dream that reflects the person’s state of soul that has resulted from a stroke of fate or from many other things. In my opinion, it is the ups and downs that are important. That which appears, that forms the picture at the edge of awakening, is only a cloak into which the dream weaves itself. When we look more closely at the world of dreams, and when we ask ourselves what a human being experiences until awakening, we will admit that until we awaken, these ups and downs of feeling clothe themselves in pictures just at the moment of awakening. Of course, we can perceive this in characteristic dreams such as this one:

Thus the entire picture of the dream flashed through his head at that moment. However, what was clothed in those pictures is a lasting state of his soul. Now you need to seriously compare what lies at the basis of these dreams—the welling up and subsiding of feelings, the tension and its resolution or perhaps the tendency toward something which then leads to some calamity and so forth. Compare that seriously with what lies at the basis of the musical element and you will find in those dream pictures only something that is irregular (not rhythmic). In music, you find something that is very similar to this welling up and subsiding and so forth. If you then continue to follow this path, you will find that sculpture and drawing imitate the form in which we find ourselves during ordinary life from awakening until falling asleep. Melodies, which are connected to music, give us the experiences of an apparently unconscious state, and they occur as reminiscences of such in our daily lives. People know so little about the actual origins of musical themes because they experience what lives in musical themes only during the period from falling asleep till awakening. This exists for human beings today as a still-unconscious element, though revealed through forming pictures in dreams. However, we need to take up this unconscious element that prevails in dreams and which also prevails as melody in music in our teaching, so that we rise above materialism. If you understand the spirit of what I have just presented, you will recognize how everywhere there has been an attempt to work with this unconscious element. I have done that first by showing how the artistic element is necessary right from the very beginning of elementary school. I have insisted that we should use the dialect that the children speak to reveal the content of grammar, that is, we should take the children’s language as such and accept it as something complete and then use it as the basis for presenting grammar. Think for a moment about what you do in such a case. In what period of life is speech actually formed? Attempt to think back as far as you can in the course of your life, and you will see that you can remember nothing from the period in which you could not speak. Human beings learn language in a period when they are still sleeping through life. If you then compare the dreamy world of the child’s soul with dreams and with how melodies are interwoven in music, you will see that they are similar. Like dreaming, learning to speak occurs through the unconscious, and is something like an awakening at dawn. Melodies simply exist and we do not know where they come from. In reality, they arise out of this sleep element of the human being. We experience a sculpting with time from the time we fall asleep until we awaken. At their present stage of development human beings are not capable of experiencing this sculpting with time. You can read about how we experience that in my book How to Know Higher Worlds. That is something that does not belong to education as such. From that description, you will see how necessary it is to take into account that unconscious element which has its effect during the time the child sleeps. It is certainly taken into account in our teaching of music, particularly in teaching musical themes, so that we must attempt to exactly analyze the musical element to the extent that it is present in children in just the same way as we analyze language as presented in sentences. In other words, we attempt to guide children at an early age to recognize themes in music, to actually feel the melodic element like a sentence. Here it begins and here it stops; here there is a connection and here begins something new. In this regard, we can have a wonderful effect upon the child’s development by bringing an understanding of the not-yet-real content of music. In this way, the child is guided back to something that exists in human nature but is almost never seen. Nearly everyone knows what a melody is and what a sentence is. But a sentence that consists of a subject, a predicate, and an object and which is in reality unconsciously a melody is something that only a few people know. Just as we experience the rising and subsiding of feelings as a rhythm in sleeping, which we then become conscious of and surround with a picture, we also, in the depths of our nature, experience a sentence as music. By conforming to the outer world, we surround what we perceive as music with something that is a picture. The child writes the essay—subject, predicate, object. A triplet is felt at the deepest core of the human being. That triplet is used through projecting the first tone in a certain way upon the child, the second upon writing, and the third upon the essay. Just as these three are felt and then surrounded with pictures (which, however, correspond to reality and are not felt as they are in dreams), the sentence lives in our higher consciousness; whereas in our deepest unconsciousness, something musical, a melody, lives. When we are aware that, at the moment we move from the sense-perceptible to the supersensible, we must rid ourselves of the sense-perceptible content, and in its place experience what eludes us in music—the theme whose real form we can experience in sleep—only then can we consider the human being as a whole. Only then do we become genuinely aware of what it means to teach language to children in such a living way that the child perceives a trace of melody in a sentence. This means we do not simply speak in a dry way, but instead in a way that gives the full tone, that presents the inner melody and subsides through the rhythmic element. Around 1850 European people lost that deeper feeling for rhythm. Before that, there was still a certain relationship to what I just described. If you look at some treatises that appeared around that time about music or about the musical themes from Beethoven and others, then you will see how at about that time those who were referred to as authorities in music often cut up and destroyed in the most unimaginable ways what lived in music. You will see how that period represents the low point of experiencing rhythm. As educators, we need to be aware of that, because we need to guide sentences themselves back to rhythm in the school. If we keep that in mind, over a longer period of time we will begin to recognize the artistic element of teaching. We would not allow the artistic element to disappear so quickly if we were required to bring it more into the content. All this is connected with a question that was presented to me yesterday and which I can more thoroughly discuss in this connection. The question was, “Why is it not possible to teach proper handwriting to those children who have such a difficult time writing properly?” Those who might study Goethe’s handwriting or that of other famous people will get the odd impression that famous people often have very strange handwriting. In education, we certainly cannot allow a child to have sloppy handwriting on the grounds that the child will probably someday be a famous person and we should not disturb him. We must not allow that to influence us. But what is actually present when a child writes in such a sloppy manner? If you make some comparisons, you will notice that sloppy handwriting generally arises from the fact that such children have a rather unmusical ear, or if not that, then a reason that is closely related to it. Children write in a sloppy way because they have not learned to hear precisely: they have not learned to hear a word in its full form. There may be different reasons why children do not hear words correctly. The child may be growing up in a family or environment where people speak unclearly. In such a case, the child does not learn to hear properly and will thus not be able to write properly, or at least not very easily. In another case, a child may tend to have little perception for what he or she hears. In that case, we need to draw the child’s attention to listening properly. In other situations it is the teacher who is responsible for the child’s poor handwriting. Teachers should pay attention to speaking clearly and also to using very descriptive language. They do not have to speak like actors, making sure to enunciate the ending syllable. But they must accustom themselves to living into each syllable, so that the syllables are clearly spoken and children will be more likely to repeat the syllables in a clear way. When you speak in a clear and complete way, you will be able to achieve a great deal with regard to proper handwriting for some children. All this is connected with the unconscious, with the dream and sleep element, since the sleep element is simply the unconscious element. It is not something we should teach to children in an artificial way. What is the basis of listening? That is normally not discussed in psychology. In the evening we fall asleep and in the morning we awake; that is all we know. We can think about it afterward by saying to ourselves that we are not conscious during that period. Conventional, nonspiritual science is unaware of what occurs to us from the time we fall asleep until we awaken. However, the inner state of our soul is no different when we are listening than when we are sleeping. The only difference is that there is a continual movement from being within ourselves to being outside ourselves. It is extremely important that we become aware of this undulation in the life of our souls. When I listen, my attention is turned toward the outer world. However, while listening, there are moments where I actually awaken within myself. If I did not have those moments, listening would be of absolutely no use. While we are listening or looking at something, there is a continual awakening and falling asleep, even though we are awake. It is a continual undulation—waking, falling asleep, waking, falling asleep. In the final analysis, our entire relationship to the external world is based upon this capacity to move into the other world, which could be expressed paradoxically as “being able to fall asleep.” What else could it mean to listen to a conversation than to fall asleep into the content of the conversation? Understanding is awakening out of the conversation, nothing more. What that means, however, is that we should not attempt to reach what should actually be developed out of the unconsciousness, out of the sleeping or dreaming of the human being in a conscious way. For that reason, we should not attempt to teach children proper handwriting in an artificial way. Instead we should teach them by properly speaking our words and then having the child repeat the words. Thus we will slowly develop the child’s hearing and therefore writing. We need to assume that if a child writes in a sloppy way, she does not hear properly. Our task is to support proper hearing in the child and not to do something that is directed more toward full consciousness than hearing is. As I mentioned yesterday, we should also take such things into account when teaching music. We must not allow artificial methods to enter into the school where, for instance, the consciousness is mistreated by such means as artificial breathing. The children should learn to breathe through grasping the melody. The children should learn to follow the melody through hearing and then adjust themselves to it. That should be an unconscious process. It must occur as a matter of course. As I mentioned, we should have the music teachers hold off on such things until the children are older, when they will be less influenced by them. Children should be taught about the melodic element in an unconscious way through a discussion of the themes. The artificial methods I mentioned have just as bad an effect as it would have to teach children drawing by showing them how to hold their arms instead of giving them a feeling for line. It would be like saying to a child, “You will be able to draw an acanthus leaf if you only learn to hold your arm in such and such a way and to move it in such and such a way.” Through this and similar methods, we do nothing more than to simply consider the human organism from a materialistic standpoint, as a machine that needs to be adjusted so it does one thing properly. If we begin from a spiritual standpoint, we will always make the detour through the soul and allow the organism to adjust itself to what is properly felt in the soul. We can therefore say that if we support the child in the drawing element, we give the child a relationship to its environment, and if we support the child in the musical element, then we give the child a relationship to something that is not in our normal environment, but in the environment we exist in from the time of falling asleep until awakening. These two polarities are then combined when we teach grammar, for instance. Here we need to interweave a feeling for the structure of a sentence with an understanding of how to form sentences. We need to know such things if we are to properly understand how beginning at approximately the age of twelve, we slowly prepare the intellectual aspect of understanding, namely, free will. Before the age of twelve, we need to protect the child from independent judgments. We attempt to base judgment upon authority so that authority has a certain unconscious effect upon the child. Through such methods we can have an effect unbeknownst to the child. Through this kind of relationship to the child, we already have an element that is very similar to the musical dreamlike element. Around the age of twelve, we can begin to move from the botanical or zoological perspective toward the mineral or physical perspective. We can also move from the historical to the geographical perspective. It is not that such things should only begin at the age of twelve, but rather before then they should be handled in such a way that we use judgment less and feeling more. In a certain sense, before the age of twelve we should teach children history by presenting complete and rounded pictures and by creating a feeling of tension that is then resolved. Thus, before the age of twelve, we will primarily take into account how we can reach the child’s feeling and imagination through what we teach about history. Only at about the age of twelve is the child mature enough to hear about causality in history and to learn about geography. If you now look at what we should teach children, you will feel the question of how we are to bring the religious element into all this so that the child gains a fully rounded picture of the world as well as a sense of the supersensible. People today are in a very difficult position in that regard. In the Waldorf School, pure externalities have kept us from following the proper pedagogical perspective in this area. Today we are unable to use all of what spiritual science can provide for education in our teaching other than to apply the consequences of it in how we teach. One of the important aspects of spiritual science is that it contains certain artistic impulses that are absorbed by human beings so that they not only simply know things, but they can do things. To put it in a more extreme way, people therefore become more adept; they can better take up life and thus can also exercise the art of education in a better way. At the present time, however, we must refrain from bringing more of what we can learn from spiritual science into education than education can absorb. We were not able to form a school based upon a particular worldview at the Waldorf School. Instead from the very beginning I stipulated that Protestant teachers would teach the Protestant religion. Religion is taught separately, and we have nothing to do with it. The Protestant teacher comes and teaches the Protestant religion, just as the Catholic religion is taught by the Catholic priest or whomever the Catholic Church designates, the rabbi teaches the Jews, and so forth. At the present time we have been unable to bring more of spiritual science in other than to provide understanding for our teaching. The Waldorf School is not a parochial school. Nevertheless the strangest things have occurred. A number of people have said that because they are not religious, they will not send their children to the Protestant, Catholic, or Jewish religion teachers. They have said that if we do not provide a religion teacher who teaches religion based solely upon a general understanding, they will not send their children to religion class at all. Thus those parents who wanted an anthroposophically oriented religion class to a certain extent forced us to provide one. This class is given, but not because we have a desire to propagate anthroposophy as a worldview. It is quite different to teach anthroposophy as a worldview than it is to use what spiritual science can provide in order to make education more fruitful. We do not attempt to provide the content. What we do attempt to provide is a capacity to do. A number of strange things then occurred. For example, a rather large number of children left the other religion classes in order to join ours. That is something we cannot prohibit. It was very uncomfortable for me, at least from the perspective of retaining a good relationship to the external world. It was also quite dangerous, but that is the way it is. From the same group of parents we hear that the teaching of other religions will soon cease anyway. That is not at all our intent, as the Waldorf School is not intended as a parochial school. Today nowhere in the civilized world is it possible to genuinely teach out of the whole. That will be possible only when through the threefold social organism cultural life becomes independent. So long as that is not the case, we will not be able to provide the same religious instruction for everybody. Thus what we have attempted to do is to make education more fruitful through spiritual science. |

| 301. The Renewal of Education: Teaching History and Geography

07 May 1920, Basel Translated by Ruth Pusch, Gertrude Teutsch Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| 301. The Renewal of Education: Teaching History and Geography

07 May 1920, Basel Translated by Ruth Pusch, Gertrude Teutsch Rudolf Steiner |

|---|