| 304a. Waldorf Education and Anthroposophy II: Educational Issues II

30 Aug 1924, London Translated by Ruth Pusch, Gertrude Teutsch, Roland Everett Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| Only when one knows the condition of the human being under the influence of these successively developing members, can one adequately guide the education and training of children. |

| He only imitated what his mother had done. When this example is understood, one knows that, in the case of young children, imitation is the thing that rules their physical and soul development. |

| Yet this inconvenience must be carried by the teacher with understanding and equanimity. The first step is for the children to learn to create resemblances of outer shapes, using color and form. |

| 304a. Waldorf Education and Anthroposophy II: Educational Issues II

30 Aug 1924, London Translated by Ruth Pusch, Gertrude Teutsch, Roland Everett Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

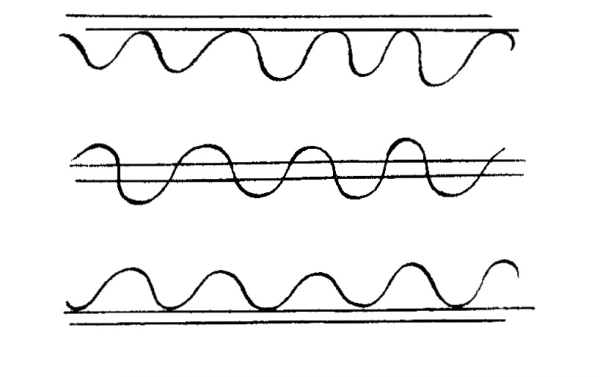

First I must thank Mrs. MacMillan and Mrs. Mackenzie for their kind words of greeting and for the beautiful way they have introduced our theme. Furthermore, I must apologize for speaking to you in German followed by an English translation. I know that this will make your understanding more difficult, but it is something I cannot avoid. What I have to tell you is not about general ideas on educational reform or formalized programs of education; basically, it is about the practice of teaching, which stands the test of time only when actually applied in classroom situations. This teaching has been practiced in the Waldorf school for several years now. It has shown tangible and noticeable results, and it has been recognized in England also; on the strength of this, it became possible, through the initiative of Mrs. Mackenzie, for me to give educational lectures in Oxford. This form of teaching is the result not only of what must be called a spiritual view of the world, but also of spiritual research. Spiritual research leads first to a knowledge of human nature, and, through that, to a knowledge of the “human being becoming,” from early childhood until death. This form of spiritual research is possible only when one acknowledges that the human being can look into the spiritual world when the necessary and relevant forces of cognition are developed. It is difficult to present in a short survey of this vast theme what normally needs to be acquired through a specific training of the human soul, with the goal of acquiring the faculty of perceiving and comprehending not just the material aspects of the human being and the sensory world, but also the spiritual element, so that this spiritual element may work in the human will. However, I will certainly try to indicate what I mean. One can strengthen and intensify inner powers of the soul, just as it is possible to research the sense-perceptible world by external experiments using instrumental aids such as the microscope, telescope, or other optical devices, through which the sense world yields more of its secrets and reveals more to our vision than in ordinary circumstances. By forging inner “soul instruments” in this way, it is possible to perceive the spiritual world in its own right through the soul’s own powers. One can then discover also the fuller nature of the human being, that what is generally understood of the human being in ordinary consciousness and through the so-called sciences is only a small part of the whole of human nature, and that beyond the physical aspect, a second human being exists. As I begin to describe this, remember that names do not matter, but we must have them. I make use of old names because they are known here and there from literature. Nevertheless, I must ask you not to be put off by these names. They do not stem from superstition, but from exact research. Nevertheless, there is no reason why one should not use other names instead. In any case, the second human member, which I shall call the etheric body, is visible when one’s soul forces have been sufficiently strengthened as a means for a deeper cognition (just as the physical senses, by means of microscope or telescope, can penetrate more deeply into the sense world). This etheric body is the first of the spiritual bodies linked with the human physical body. When studying the physical human being only from the viewpoint of conventional science, one cannot really understand how the physical body of the human being can exist throughout a lifetime. This is because, in reality, most physical substances in the body disappear within a period of seven to eight years. No one sitting here is the same, physically speaking, as the person of some seven or eight years ago! The substances that made up the body then have in the meantime been cast off, and new ones have taken their place. In the etheric body we have the first real supersensible entity, which rules and permeates us with forces of growth and nourishment throughout earthly life. The ether body is the first supersensible body to consider. The human being has an ether body, just as plants do, but minerals do not. The only thing we have in common with the minerals is a physical form. However, furnished with those specially developed inner senses and perceptions developed by powers of the soul, we come to recognize also a third sheath or member of the human being, which we call the astral body. (Again I must ask you not to be disturbed by the name.) The human being has an astral body, as do animals. We experience sensation through the astral body. An organism such as the plant, which can grow and nourish itself, does not need sensation, but human beings and animals can sense. The astral body cannot be designated by an abstract word, because it is a reality. And then we find something that makes the human being into a bearer of three bodies, an entity that controls the physical, etheric, and astral bodies. It is the I, the real inner spiritual core of the human being. So the four members are first the physical body, second the etheric body, third the astral body, and finally the human I-organization. Let those who are not aware of these four members of the human being—those who believe that external observation, such as in anatomy and physiology, encompasses the entire human being—try to find a world view! It is possible to formulate ideas in many ways, whether or not they are accepted by the world. Accordingly one may be a spiritualist, an idealist, a materialist, or a realist. It is not difficult to establish views of the world, because one only needs to formulate them verbally; one only needs to maintain a belief in one or another viewpoint. But unless one’s world views stem from actual realities and from real observations and experiences, they are of no use for dealing with the external aspect of the human being, nor for education. Let’s suppose you are a bridge builder and base your mechanical construction on a faulty principle: the bridge will collapse as the first train crosses it. When working with mechanics, realistic or unrealistic assumptions will prove right or wrong immediately. The same is true in practical life when dealing with human beings. It is very possible to digest world views from treatises or books, but one cannot educate on this basis; it is only possible to do so on the strength of a real knowledge of the human being. This kind of knowledge is what I want to speak about, because it is the only real preparation for the teaching profession. All external knowledge that, no matter how ingeniously contrived, tells a teacher what to do and how to do it, is far less important than the teacher’s ability to look into human nature itself and, from a love for education and the art of education, allow the child’s own nature to tell the teacher how and what to teach. Even with this knowledge, however—a knowledge strengthened by supersensible perception of the human being—we will find it impossible during the first seven years of the child’s life, from birth to the second dentition, to differentiate between the four human members or sheaths of which I have just spoken. One cannot say that the young child consists of physical body, etheric body, astral body and I, in the same way as in the case of an adult. Why not? A newborn baby is truly the greatest wonder to be found in all earthly life. Anyone who is open-minded is certain to experience this. A child enters the world with a still unformed physiognomy, an almost “neutral” physiognomy, and with jerky and uncoordinated movements. We may feel, possibly with a sense of superiority, that a baby is not yet suited to live in this world, that it is not yet fit for earthly experience. The child lacks the primitive skill of grasping objects properly; it cannot yet focus its eyes properly, cannot express the dictates of the will through limb movement. One of the most sublime experiences is to see gradually evolve, out of the central core of human nature, out of inner forces, that which gives the physiognomy its godlike features, what coordinates the limb movements to suit outer conditions, and so on. And yet, if one observes the child from a supersensible perspective, one cannot say that the child has a physical, etheric, and astral body plus an I, just as one cannot say that water in its natural state is composed of hydrogen and oxygen. Water does consist of hydrogen and oxygen, but these two elements are most intimately fused together. Similarly, in the child’s organism until the change of teeth, the four human members are so intimately merged together that for the time being it is impossible to differentiate between them. Only with the change of teeth, around the seventh year, when children enter primary education, does the etheric body come into its own as the basis of growth, nutrition, and so on; it is also the basis for imagination, for the forces of mind and soul, and for the forces of love. If one observes a child of seven with supersensible vision, it is as if a supersensible etheric cloud were emerging, containing forces that were as yet little in control because, prior to the change of teeth, they were still deeply embedded in the physical organism and accustomed to working homogeneously within the physical body. With the coming of the second teeth they become freer to work more independently, sending down into the physical body only a portion of their forces. The surplus then works in the processes of growth, nutrition, and so on, but also has free reign in supporting the child’s life of imagination. These etheric forces do not yet work in the intellectual sphere, in thinking or ideas, but they want to appear on a higher level than the physical in a love for things and in a love for human beings. The soul has become free in the child’s etheric body. Having gone through the change of teeth the child, basically, has become a different being. Now another life period begins, from the change of teeth until puberty. When the child reaches sexual maturity, the astral body, which so far could be differentiated only very little, emerges. One notices that the child gains a different relationship to the outer world. The more the astral body is born, the greater the change in the child. Previously it was as if the astral body were embedded in the physical and etheric organization. Thus to summarize: First, physical birth occurs when the embryo leaves the maternal body. Second, the etheric body is born when the child’s own etheric body wrests itself free. Due to the emergence of the etheric body we can begin to teach the child. Third, the astral body emerges with the coming of puberty, which enables the adolescent to develop a loving interest in the outside world and to experience the differences between human beings, because sexual maturity is linked not only with an awakening of sexual love, but also with a knowledge gained through the adolescent’s immersion in all aspects of life. Fourth, I-consciousness is born only in the twenty-first or twenty-second year. Only then does the human being become an independent I-being. Thus, when speaking about the human being from a spiritual perspective, one can speak of four successive births. Only when one knows the condition of the human being under the influence of these successively developing members, can one adequately guide the education and training of children. For what does it mean if, prior to the change of teeth, the physical body, the etheric body, the astral body, and the I cannot yet be differentiated? It means that they are merged, like hydrogen and oxygen in water. This, in turn, means that the child really is as yet entirely a sense organ. Everything is related to the child in the same way a sense impression is related to the sense organ; whatever the child absorbs, is absorbed as in a sense organ. Look at the wonderful creation of the human eye. The whole world is reflected within the eye in images. We can say that the world is both outside and inside the eye. In the young child we have the same situation; the world is out there, and the world is also within the child. The child is entirely a sense organ. We adults taste sugar in the mouth, tongue, and palate. The child is entirely permeated by the taste. One only needs eyes to observe that the child is an organ of taste through and through. When looking at the world, the child’s whole being partakes of this activity, is surrendered to the visible surroundings. Consequently a characteristic trait follows in children; they are naturally pious. Children surrender to parents and educators in the same way that the eye surrenders to the world. If the eye could see itself, it could not see anything else. Children live entirely in the environment. They also absorb impressions physically. Let’s take the case of a father with a disposition to anger and to sudden outbursts of fury, who lives closely with a child. He does all kinds of things, and his anger is expressed in his gestures. The child perceives these gestures very differently than one might imagine. The young child perceives in these gestures also the father’s moral quality. What the child sees inwardly is bathed in a moral light. In this way the child is inwardly saturated by the outbursts of an angry father, by the gentle love of a mother, or by the influence of anyone else nearby. This affects the child, even into the physical body. Our being, as adults, enters a child’s being just as the candlelight enters the eye. Whatever we are around a child spreads its influence so that the child’s blood circulates differently in the sense organs and in the nerves; since these operate differently in the muscles and vascular liquids which nourish them, the entire being of the child is transformed according to the external sense impressions received. One can notice the effect that the moral and religious environment of childhood has had on an old person, including the physical constitution. A child’s future condition of health and illness depends on our ability to realize deeply enough that everything in the child’s environment is mirrored in the child. The physical element, as well as the moral element, is reflected and affects a person’s health or illness later. During the first seven years, until the change of teeth, children are purely imitative beings. We should not preconceive what they should do. We must simply act for them what we want them to do. The only healthy way to teach children of this age is to do in front of them what we wish them to copy. Whatever we do in their presence will be absorbed by their physical organs. And children will not learn anything unless we do it in front of them. In this respect one can have some interesting experiences. Once a father came to me because he was very upset. He told me that his five-year-old child had stolen. He said to me, “This child will grow into a dreadful person, because he has stolen already at this tender age.” I replied, “Let us first discover whether the boy has really stolen.” And what did we find? The boy had taken money out of the chest of drawers from which his mother habitually took money whenever she needed it for the household. The mother was the very person whom the boy imitated most. To the child it was a matter of course to do what his mother did, and so he too took money from the drawer. There was no question of his thieving, for he only did what was natural for a child below the age of the second dentition: he imitated. He only imitated what his mother had done. When this example is understood, one knows that, in the case of young children, imitation is the thing that rules their physical and soul development. As educators we must realize that during these first seven years we adults are instrumental in developing the child’s body, soul, and spirit. Education and upbringing during these first seven years must be formative. If one can see through this situation properly, one can recognize in people’s physiognomy, in their gait, and in their other habits, whether as children they were surrounded by anger or by kindness and gentleness, which, working into the blood formation and circulation, and into the individual character of the muscular system, have left lasting marks on the person. Body, soul, and spirit are formed during these years, and as teachers we must know that this is so. Out of this knowledge and impulse, and out of the teacher’s ensuing enthusiasm, the appropriate methods and impulses of feeling and will originate in one’s teaching. An attitude of dedication and self-sacrifice has to be the foundation of educational methods. The most beautiful pedagogical ideas are without value unless they have grown out of knowledge of the child and unless the teachers can grow along with their students, to the extent that the children may safely imitate them, thus recreating the teachers’ qualities in their own being. For the reasons mentioned, I would like to call the education of the child until the change of teeth “formative education,” because everything is directed toward forming the child’s body, soul, and spirit for all of earthly life. One only has to look carefully at this process of formation. I have quoted the example of an angry father. In the gesture of a passionate temperament, the child perceives inherent moral or immoral qualities. These affect the child so that they enter the physical constitution. It may happen that a fifty-year-old person begins to develop cataracts in the eyes and needs an operation. These things are accepted and seen only from the present medical perspective. It looks as if there is a cataract, and this is the way to treat it, and there the matter ends; the preceding course of life is not considered. If one were ready to do that, it would be found that a cataract can often be traced back to the inner shocks experienced by the young child of an angry father. In such cases, what is at work in the moral and religious sphere of the environment spreads its influence into the bodily realm, right down to the vascular system, eventually leading to health or illness. This often surfaces only later in life, and the doctor then makes a diagnosis based on current circumstances. In reality, we are led back to the fact that, for example, gout or rheumatism at the age of fifty or sixty can be linked to an attitude of carelessness, untidiness, or disharmony that ruled the environment of such a patient during childhood. These circumstances were absorbed by the child and entered the organic sphere. If one observes what a child has absorbed during the stage of imitation up to the change of teeth, one can recognize that the human being at this time is molded for the whole of life. Unless we learn to direct rightly the formative powers in the young human being, all our early childhood education is without value. We must allow for germination of the forces that control health and illness for all of earthly life. With the change of teeth, the etheric body emerges, controlling the forces of digestion, nutrition, and growth, and it begins to manifest in the realm of the soul through the faculty of fantasy, memory, and so on. We must be clear about what we are educating during the years between the second dentition and puberty. What are we educating in the child during this period? We are working with the same forces that effect proper digestion and enable the child to grow. They are transformed forces of growth, working freely now within the soul realm. What do nature and the spiritual world give to the human being through the etheric body’s forces of growth? Life—actual life itself! Since we cannot bestow life directly as nature does during the first seven years, and since it is our task to work on the liberated etheric body in the soul realm, what should we, as teachers, give the child? We should give life! But we cannot do this if, at such an early stage, we introduce finished concepts to the child. The child is not mature enough yet for intellectual work, but is mature enough for imagery, for imagination, and for memory training. With the recognition of what needs to be done at this age, one knows that everything taught must have the breath of life. Everything needs to be enlivened. Between the change of teeth and puberty, the appropriate principle is to bestow life through all teaching. Everything the teacher does, must enliven the student. However, at just this age, it is really too easy to bring death with one’s teaching. As correctly demanded by civilization, our children must be taught reading and writing. But now consider how alien and strange the letters of the alphabet are to a child. In themselves letters are so abstract and obscure that, when the Europeans, those so-called superior people, came to America (examples of this exist from the 1840s), the Native Americans said: “These Europeans use such strange signs on paper. They look at them and then they put what is written on paper into words. These signs are little devils!” Thus said the Native Americans: “The Palefaces [as they called the Europeans] use these little demons.” For the young child, just as for the Indians, the letters are little demons, for the child has no immediate relationship to them. If we introduce reading abstractly right away, we kill a great deal in the child. This makes no sense to anyone who can see through these matters. Consequently, educational principles based on a real knowledge of the human being will refer to the ancient Egyptian way of writing. They still put down what they had actually seen, making a picture of it. These hieroglyphics gave rise to our present letters. The ancient Egyptians did not write letters, they painted pictures. Cuneiform writing has a similar origin. In Sanskrit writing one can still see how the letters came from pictures. You must remember that this is the path humanity has gone on its way to modern abstract letters, to which we no longer have an immediate relationship. What then can we do? The solution is to not plague children at all with writing and reading from the time they begin school. Instead, we have them draw and paint. When we guide children in color and form by painting, the whole body participates. We let children paint the forms and shapes of what they see. Then the pictures are guided into the appropriate sounds. Let’s take, for example, the English word fish. By combining the activity of painting and drawing with a brush, the child manages to make a picture of a fish. Now we can ask the child to pronounce the word fish, but very slowly. After this, one could say, “Now sound only the beginning of the word: ‘F.’” In this way the letter F emerges from the picture that was painted of the fish. One can proceed in a similar way with all consonant sounds. With the vowels, one can lead from the picture to the letters by taking examples from a person’s inner life of feeling. In this way, beginning at the age of seven or eight, children learn a combined form of painting and drawing. Teachers can hardly relax during this activity, because painting lessons with young children inevitably create a big mess, which always has to be cleaned up at the end of the lesson. Yet this inconvenience must be carried by the teacher with understanding and equanimity. The first step is for the children to learn to create resemblances of outer shapes, using color and form. This leads to writing. In learning to write, the child brings the whole body into movement, not just one part. Only the head is involved when we read, which is the third step, after writing. This happens around the ninth year, when the child learns to read through the activity of writing, which was developed from painting. In doing this, the child’s nature gives us the cue, and the child’s nature always directs us in how to proceed. This means that teachers are forced to become different human beings. They can’t learn their lessons and then apply them abstractly; they must instead stand before the class as whole human beings, and for everything they do, they must find images; they must cultivate their imagination. The teachers can then communicate their intentions to the students in imperceptible ways. The teachers themselves have to be alert and alive. They will reach the child to the extent that they can offer imaginative pictures instead of abstract concepts. It is even possible to bring moral and religious concepts through the medium of pictures. Let us assume that teachers wish to speak to children about the immortality of the human soul. They could speak about the butterfly hidden in a chrysalis. A small hole appears in the chrysalis, and the butterfly emerges. Teachers could talk to children as follows: The butterfly, emerging from the chrysalis, shows you what happens when a person dies. While alive, the person is like the chrysalis. The soul, like the butterfly, flies out of the body only at death. The butterfly is visible when it leaves the chrysalis. Although we cannot see the soul with our eyes when a person dies, it nevertheless flies into the spiritual world like a butterfly from the chrysalis. There are, however, two ways teachers can proceed. If they feel inwardly superior to the children, they will not succeed in using this simile. They may think they are very smart and that the children’s ignorance forces them to invent something that gets the idea of immortality across, while they themselves do not believe this butterfly and chrysalis “humbug,” and consider it only a useful ploy. As a result they fail to make any lasting impression on the children; for here, in the depths of the soul, forces work between teacher and child. If I, as the teacher, believe that spiritual forces in nature, operating at the level of the newly-emerged butterfly, provide an image of immortality, if I am fully alive in this image of the butterfly emerging from the chrysalis, then my comparison will work strongly on the child’s soul. This simile will work like a seed, and grow properly in the child, working beneficently on the soul. This is an example of how we can keep our concepts mobile, because it would be the greatest mistake to approach a child directly with frozen intellectual concepts. If one buys new shoes for a three-year-old, one would hardly expect the child to still be wearing them at nine. The child would then need different, larger shoes. And yet, when it comes to teaching young children, people often act exactly like this, expecting the student to retain unchanged, possibly until the age of forty or fifty, what was learned at a young age. They tend to give definitions, meant to remain unchanged like the metaphorical shoes given to a child of three, as if the child would not outgrow their usefulness later in life! The point is that, when educating we must allow the soul to grow according to the demands of nature and the growing physical body. Teachers can give a child living concepts that grow with the human being only when they acquire the necessary liveliness to permeate all their teaching with imagination. We need education that enlivens the human being during the years between the change of teeth and puberty. The etheric body can then become free. For example, take the word mouth. If I pronounce only the first letter, “M,” I can transform this line as picture of a mouth to this:  Similarly, I can find other ways to use living pictures to bridge the gap to written letters of the alphabet. Then, if the intellect (which is meant to be developed only at puberty) is not called on too soon, the ideas born out of the teacher’s imagination will grow with the child. Definitions are poison to the child. This always brings to mind a definition that once was made in a Greek philosophers’ school. The question, “What is a human being?” received the answer, “A human being is a creature with two legs and no feathers.” The following day, a student of the school brought a goose whose feathers had been plucked out, maintaining that this was a human being—a creature with two legs and without feathers. (Incidentally, this type of definition can sometimes be found in contemporary scientific literature. I know that in saying this I am speaking heresy, but roughly speaking, this is the kind of intellectual concept we often offer children.) We need rich, imaginative concepts, that can grow with the child, concepts that allow growth forces to remain active even when a person reaches old age. If children are taught only abstract concepts, they will display signs of aging early in life. We lose fresh spontaneity and stop making human progress. It is a terrifying experience when we realize we have not grown up with fantasy, with images, with pictures that grow and live and are suited to the etheric body, but instead we grew up merely with those suited to abstraction, to intellectualism—that is, to death. When we recognize that the etheric body really exists, that it is a living reality—when we know it not just in theory but from observing a developing child—then we will experience the second golden principle of education, engraved in our hearts. The golden principle during the first seven years is: Mold the child’s being in a manner worthy of human imitation, and thus cultivate the child’s health. During the second seven years, from the change of teeth to puberty, the guiding motive or principle of education should be: Enliven the students, because their etheric bodies have been entrusted to your care. With the coming of puberty, what I have called the astral body is freed in a new kind of birth. This is the very force that, during the age of primary education until the beginning of puberty, was at the base of the child’s inmost human forces, in the life of feeling. This force then lived undifferentiated within the latent astral body, still undivided from the physical and etheric bodies. This spiritual aggregate is entrusted to the quality of the teachers’ imaginative handling, and to their sensitive feeling and tact. As the child’s astral body is gradually liberated from the physical organization, becoming free to work in the soul realm, the child is also freed from what previously had to be present as a natural faith in the teacher’s authority. What I described earlier as the only appropriate form of education between the change of teeth and puberty has to come under the auspices of a teacher’s natural authority. Oh! It is such great fortune for all of life when, at just this age, children can look up to their teachers as people who wield natural authority, so that what is truth for the teacher, is also very naturally truth to the students. Children cannot, out of their own powers, discriminate between something true and something false. They respect as truth what the teacher calls the truth. Because the teacher opens the child’s eyes to goodness, the child respects goodness. The child finds truth, goodness, and beauty in the world through venerating the personality of the teacher. Surely no one expects that I, who, many years ago, wrote Intuitive Thinking as a Spiritual Path: A Philosophy of Freedom, would stand for the principle of authoritarianism in social life. I am saying here that the child, between the second dentition and puberty, has to experience the feeling of a natural authority from the adults in charge, and that, during these years, everything the student receives must be truly alive. The educator must be the unquestioned authority at this age, because the human being is ready for freedom only after having learned to respect and venerate the natural authority of a teacher. Only after reaching sexual maturity, when the astral body has become the means for individual judgments, can the student form judgments instead of accepting those of the teacher. Now what must be considered the third principle of education comes into its own. The first one I called “the formative element,” the second one “the enlivening element.” The third element of education, which enters with puberty, can be properly called “an awakening education.” Everything taught after puberty must affect adolescents so that their emerging independent judgment appears as a continual awakening. If one attempts to drill subjects into a student who has reached puberty, one tyrannizes the adolescent, making the student into a slave. If, on the other hand, one’s teaching is arranged so that, from puberty on, adolescents receive their subject matter as if they were being awakened from a sleep, they learn to depend on their own judgments, because with regard to making their own judgments, they were indeed asleep. The students should now feel they are calling on their own individuality, and all education, all teaching, will be perceived as a stimulus and awakener. This can be realized when teachers have proceeded as I have indicated for the first two life periods. This last stage in education will then have a quality of awakening. And if in their style, posture, and presentation, teachers demonstrate that they are themselves permeated with the quality of awakening, their teaching will be such that what must come from those learning will truly come from them. The process should reach a kind of dramatic intensification when adolescents inwardly join with active participation in the lessons, an activity that proceeds very particularly from the astral body. Appealing properly in this way to the astral body, we address the immortal being of the student. The physical body is renewed and exchanged every seven years. The etheric body gives its strength as a dynamic force and lasts from birth, or conception, until death. What later emerges as the astral body represents, as already mentioned, the eternal kernel of the human being, which descends to Earth, enveloping itself with the sheaths of the physical and etheric bodies before passing again through the portal of death. We address this astral body properly only when, during the two previous life periods, we have related correctly to the child’s etheric and physical bodies, which the human being receives only as an Earth dweller. If we have educated the child as described so far, the eternal core of the human individuality, which is to awaken at puberty, develops in an inwardly miraculous way, not through our guidance, but through the guidance of the spiritual world itself. Then we may confidently say to ourselves that we have taken the right path in educating children, because we did not force the subject matter on them; neither did we dictate our own attitude to them, because we were content to remove the hurdles and obstacles from the way so that their eternal core could enter life openly and freely. And now, during the last stage, our education must take the form of awakening the students. We make our stand in the school saying, “We are the cultivators of the divine-spiritual world order; we are its collaborators and want to nurture the eternal in the human being.” We must be able to say this to ourselves or feel ashamed. Perhaps, sitting there among our students are one or two geniuses who will one day know much more than we teachers ever will. And what we as teachers can do to justify working with students, who one day may far surpass us in soul and spirit, and possibly also in physical strength, is to say to ourselves: Only when we nurture spirit and soul in the child—nurture is the word, not overpower—only when we aid the development of the seed planted in the child by the divine-spiritual world, only when we become “spiritual midwives,” then we will have acted correctly as teachers. We can accomplish this by working as described, and our insight into human nature will guide us in the task. Having listened to my talk about the educational methods of the Waldorf school, you may wonder whether they imply that all teachers there have the gift of supersensible insight, and whether they can observe the births of the etheric and astral bodies. Can they really observe the unfolding of human forces in their students with the same clarity investigators use in experimental psychology or science to observe outer phenomena with the aid of a microscope? The answer is that certainly not every teacher in the Waldorf school has developed sufficient clairvoyant powers to see these things with inward eyes, but it isn’t necessary. If we know what spiritual research can tell us about the human being’s physical, etheric, and astral bodies and about the human I-organization, we need only to use our healthy soul powers and common sense, not just to understand what the spiritual investigator is talking about, but also to comprehend all its weight and significance. We often come across very strange attitudes, especially these days. I once gave a lecture that was publicly criticized afterward. In this lecture I said that the findings of a clairvoyant person’s investigations can be understood by anyone of sane mind who is free of bias. I meant this literally, and not in any superstitious sense. I meant that a clairvoyant person can see the supersensible in the human being just as others can see the sense-perceptible in outer nature. The reply was, “This is what Rudolf Steiner asserted, but evidently it cannot be true, because if someone maintains that a supersensible spiritual world exists and that one can recognize it, one cannot be of sane mind; and if one is of sane mind, one does not make such an assertion....” Here you can see the state of affairs in our materialist age, but it has to be overcome. Not every Waldorf teacher has the gift of clairvoyance, but every one of them has accepted wholeheartedly and with full understanding the results of spiritual-scientific investigation concerning the human being. And each Waldorf teacher applies this knowledge with heart and soul, because the child is the greatest teacher, and while one cares for the child, witnessing the wonderful development daily, weekly, and yearly, nothing can awaken the teacher more to the needs of education. In educating the child, in the daily lessons, and in the daily social life at school, the teachers find the confirmation for what spiritual science can tell them about practical teaching. Every day they grow into their tasks with increasing inner clarity. In this way, education and teaching in the Waldorf school are life itself. The school is an organism, and the teaching faculty is its soul, which, in the classrooms, in regular common study, and in the daily cooperative life within the school organism, radiates care for the individual lives of the students in all the classes. This is how we see the possibility of carrying into our civilization what human nature itself demands in these three stages of education—the formative education before the change of teeth, the life-giving education between the change of teeth and puberty, and the awakening education after puberty, leading students into full life, which itself increasingly awakens the human individuality.

When we look at the child properly, the following thoughts may stimulate us: In our teaching and educating we should really become priests, because what we meet in children reveals to us, in the form of outer reality and in the strongest, grandest, and most intense ways, the divine-spiritual world order that is at the foundation of outer physical, material existence. In children we see, revealed in matter in a most sublime way, what the creative spiritual powers are carrying behind the outer material world. We have been placed next to children in order that spirit properly germinates, grows, and bears fruit. This attitude of reverence must underlie every method. The most rational and carefully planned methods make sense only when seen in this light. Indeed, when our methods are illuminated by the light of these results, the children will come alive as soon as the teacher enters the classroom. Teaching will then become the most important leaven and the most important impulse in our present stage of evolution. Those who can clearly see the present time with its tendency toward decadence and decline know how badly our civilization needs revitalization. School life and education can be the most revitalizing force. Society should therefore take hold of them in their spiritual foundations; society should begin with the human being as its fundamental core. If we start with the child, we can provide society and humanity with what the signs of the times demand from us in our present stage of civilization, for the benefit of the immediate future. |

| 305. Spiritual Ground of Education: The Necessity for a Spiritual Insight

16 Aug 1922, Oxford Translated by Daphne Harwood Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| Mackenzie, the organiser of this conference, in particular, and to the whole committee who undertook to arrange the lectures here. I feel deep gratitude because this makes it possible to give expression to what, in a sense, is indeed a new thing in the environment of that revered antiquity which alone can sponsor it. |

| Conviction, when the isolation of our worldly life and worldly outlook makes us ask: “What is the eternal, super-sensible reality underlying the world of sense-perception?” We may have beliefs as to what we were before birth in the womb of divine, super-sensible worlds. |

| Perhaps it will take the form of a great love and attachment felt for some grown-up person. But we must understand how rightly to observe what is happening in the child at this critical time. The child suddenly finds himself isolated. |

| 305. Spiritual Ground of Education: The Necessity for a Spiritual Insight

16 Aug 1922, Oxford Translated by Daphne Harwood Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

My first words shall be to ask your forgiveness that I cannot speak to you in the language of this country. But as I lack practise I must needs formulate things in the language I can use. Any disadvantage this involves will be made good, I trust, in the translation to follow. In the second place, allow me to say that I feel extra-ordinarily grateful to the distinguished committee which enables me to hold these lectures at this gathering in Oxford. I feel it an especial honour to be able to give these lectures here, in this venerable town. It was here, in this town, that I myself experienced the grandeur of ancient tradition, twenty years ago. And now that I am about to speak of a method of education which in a sense may be called new, I should like to say: In our day novelty is sought by many simply qua novelty, but whoever strives for a new thing in any sphere of human culture must first win the right to do so by knowing how to respect what is old. Here in Oxford I feel how the power of what lives in these old traditions inspires everything. And one who can feel this has perhaps the right also to speak of what is new. For a new thing, in order to maintain itself, must be rooted in the venerable past. Perhaps it is the tragedy and the great failing of our age that there is a constant demand for this new thing and that new thing, while so few people are inclined worthily to create the new from out of the old. Therefore, I feel such deep thankfulness to Mrs. Mackenzie, the organiser of this conference, in particular, and to the whole committee who undertook to arrange the lectures here. I feel deep gratitude because this makes it possible to give expression to what, in a sense, is indeed a new thing in the environment of that revered antiquity which alone can sponsor it. I am equally grateful for the very kind words of introduction which Principal Jacks spoke in this place yesterday. And now I have already indicated, perhaps, the stand-point from which these lectures will be given: what will be said here concerning education and teaching is based on that spiritual-scientific knowledge which I have made it my life's work to develop. This spiritual science was cultivated to begin with for its own sake; in recent years friends have come forward to carry it also into particular domains of practical life. Thus it was Emil Molt, of Stuttgart, who having acquaintance with the work in spiritual science going forward at the Goetheanum—(in Dornach, Switzerland)—wished to see it applied in the education of children at school. And this led to the founding of the Waldorf School in Stuttgart. The pedagogy and didactic of the Waldorf School in Stuttgart was founded in that spiritual life which, I hold, must lead to a renewal of education in conformity with the spirit of our age: a renewal of education along the lines demanded by the spirit of the age, by the tasks and the stage of human development which belong to this epoch. The education and curriculum in question is based entirely upon knowledge of man. A knowledge of man which spans man's whole being from his birth to his death. But a knowledge which aims at comprising all the super-sensible part of man's being between birth and death, all that bears lasting witness that man belongs to a super-sensible world. In our age we have spiritual life of many kinds, but above all a spiritual life coming down to us from ancient times, a spiritual life handed down by tradition. Alongside of this spiritual life and in ever diminishing contact with it, we have the life that flows to us from the magnificent discoveries of modern natural science. In an age which includes the life-time of the great natural scientists, the leading spirits in natural science, we cannot, when speaking of spiritual life neglect the potent contribution to knowledge of man made by natural science itself. Now this natural science can give us insight into the bodily nature of man, can give us insight into bodily, physio-logical functions during man's physical life. But this same natural science conducted as it is by experiment with external tools, by observation with external senses has not succeeded, for all its great progress, in reaching the essentially spiritual life of man. I do not say this in disparagement. It was the great task of natural science as systematised, for example, by such a personality as Huxley—it was the great service it rendered that for once it looked at nature with complete disregard of everything spiritual in the world. Neither, therefore, can the knowledge of man we have in psychology and anthropology help us to a practical grasp of what is spiritual. We have, in our modern civilisation a life of the spirit, and the various religious denominations maintain and spread this life of the spirit. But this spiritual culture is not capable of giving answers to man's questions as to the nature of that eternity and immortality, the super-sensible life, to which he belongs. It cannot give us conviction. Conviction, when the isolation of our worldly life and worldly outlook makes us ask: “What is the eternal, super-sensible reality underlying the world of sense-perception?” We may have beliefs as to what we were before birth in the womb of divine, super-sensible worlds. We may form beliefs as to what our souls will have to go through after passing the portal of death. And we may formulate such beliefs into a cult. This can warm our hearts and cheer our spirits. We can say to ourselves: “Man is a greater being in the whole universe than in this physical life between birth and death.” But what we achieve in this way remains a belief, it remains a thing we think and feel. It is becoming increasingly difficult to put in practice the great findings and tenets of natural science while still holding such spiritual beliefs. We know of the spirit, we no longer understand how to use the spirit, how to do anything with it, how to permeate our work and daily life with spirit. What domain of life most calls for a dealing with the spirit? The domain of teaching and education. In education we must comprehend man as a whole; and man in his totality is body, soul and spirit. We must be able to deal with spirit if we would educate. In all ages it has been incumbent on man to take account of the spirit and work by its power: now above all, because we have made such advances in external science, this summons to work with the spirit is the most urgent. Hence the social question to-day is first and foremost a question of education. For to-day we may justly ask: What must we do to give rise to social organisation and social institutions less tragic than those of the present day, less full of menace? We can give ourselves no answer but this: First we must place into practical life, into the social community, men who are educated from out of the spirit, by means of a creative activity of the spirit. The kind of knowledge we are describing pre-supposes a continuous doing in life, a dealing with life; hence it must seek out the spirituality within life and make this the basis of education throughout the differing life-epochs. For in a child the spirit is closer to the body than it is in the adult. We can see in a child how physical nature is formed plastically by the spirit. What precisely is the brain of a child when it is first born, according to our modern natural science? It is something like the clay which a sculptor takes up when he prepares a model. And now let us look at the brain of a seven year old child when we begin his primary education; it has become a wonderful work of art, but a work of art which must be worked upon further, worked upon right up to the end of school life. Hidden spiritual powers are working at the moulding of the human body. And we as educators are called upon to contribute to that work. Are called upon not only to observe the bodily nature, but—while we must never neglect the bodily nature—to observe in this bodily nature how the spirit is at work upon it. We are called upon to work with the unconscious spirit—to link ourselves not only with the natural, but with the divine ordering of the world. When we confront education earnestly it is demanded of us not only to acknowledge God for the peace of our soul, but to will God's will, to act the intentions of God. To do this however, we need a spiritual basis for education. Of this spiritual basis for education I will speak to you in the following days. We must feel when we observe child life how necessary it is to have a spiritual insight, a spiritual vision if we are adequately to follow what takes place in the child day by day, what takes place in his soul, in his spirit. We should consider how child life in its very earliest days and weeks differs totally from later childhood, let alone adulthood. We should call to mind what a large proportion of sleep a child needs in the early days of its life. And we must ask ourselves what takes place in that interchange between spirit and body when a child in early childhood needs nearly 22 hours sleep? The current attitude to such things, both in philosophy and practical life, is: Well it is not possible to see into the soul of a child, any more than one can see into the soul of an animal or of a plant; here we encounter limits of human knowledge. The spiritual view which we are here representing does not say: Here are limits of human knowledge, of human cognition. It says: We must bring forth from the depths of human nature powers of cognition equal to observing man's complete nature, body, soul and spirit; just as we can observe the arrangement of the human eye or the human ear in physiology. If in ordinary life we have not so far got this knowledge owing to our natural scientific education, we must set about building it up. Hence I shall have to speak to you of the development of a knowledge which can guarantee a genuine insight into the inner texture of child life. And devoted and unprejudiced observation of life itself goes far to bring about such an insight. We look at a child. If our view is merely external we cannot actually find any definite points of development from birth on to about the twentieth year. We look upon everything as a continuous development. It is not so for one who comes to the observation of child life equipped with the knowledge of which I shall have to speak in the next few days. Then the child is fundamentally a different being up to his seventh year or eighth year,—when the change of teeth sets in—from what he is later in life, from the change of teeth to about the fourteenth year, to puberty. And infinitely significant problems confront us when we endeavour to sink deep into the child's life and to ask. How does the soul and spirit work upon the child up to the change of teeth? How does the soul and spirit work upon the child when we have to educate and teach him in the elementary or primary school? How must we ourselves co-operate here with the soul and spirit? We see for example how speech is developed instinctively during the first period of a child's life up to the change of teeth,—instinctively as far as the child is concerned, and instinctively as regards his surroundings. Nowadays we devote a good deal of thought to the question of how a child learns to speak (I will not go into the historical aspect of the origin of speech to-day.) But how does a child actually learn to speak? Has he some kind of instinct whereby he makes his own the sounds he hears about him? Or does he derive the impulse for speech from some other kind of connection with his surroundings? If, however, one looks more closely into the life of a child one can observe that all speech and all learning to speak rests upon the imitation of what the child observes in his surroundings by means of his senses—observes unconsciously. The whole life of the child up to his seventh year is a continuous imitation of what takes place in his environment. And the moment a child perceives something, whether it be a movement, or whether it be a sound, there arises in him the impulse of an inward gesture, to re-live what has been perceived with the whole intensity of his inner nature. We only understand a child when we contemplate him as we should contemplate the eye or the ear of an older person. For the child is entirely sense-organ (i.e. a child up to the seventh year). His blood is driven through his body in a far livelier way than in later life. We can perceive by means of a fine physiology what the development of our sense-organs, for example the eye, depends on Blood preponderates in the process of development of the eye, in the very early years. Then, later, the nerve life in the senses preponderates more and more. For the development of the organism of the senses in man is a development from blood circulation to nerve activity. It is possible to acquire a delicate faculty for perceiving how the life of the blood gradually goes over into the life of the nerves. And as it is with a single sense (e.g. the eye), so it is with the whole human being. The child needs so much sleep because it is entirely sense-organ. Because it could not otherwise endure the dazzle and noise of the outer world. Just as the eye must shut itself against the dazzling sunlight, so must this sense-organ: child—for the child is entirely sense-organ—shut itself off against the world, so must it sleep a great deal. For whenever it is confronted with the world, it has to observe, to hold inward converse. Every sound of speech arises from an inward gesture. What I am now saying from out of a spiritual knowledge is—let me say—open to-day to scientific demonstration. There is a scientific discovery—and, forgive the personal allusion, but this discovery has dogged me all through my life and is just as old as I am myself, it was made in the year in which I was born. Now the discovery is to the effect that human speech depends on the left parietal con-volution of the brain. This is developed plastically in the brain. But the whole of this development takes place during childhood by means of these plastic forces of which I have spoken. And if we contemplate the whole connection which exists between the gestures of the right arm, and the right hand (which preponderate in normal children), we shall see how speech forms itself from out of gesture by imitation of the environment through an inner, secret connection between blood, nerves and the convolution of the brain: (of left-handed children and their relation to the generality of children I shall have something to say later; they form an exception, but they prove very well how what builds up the power of speech is bound up with every single gesture of the right arm and hand, even down to minutest details). If we had a more delicate physiology than our physiology of to-day, we should be able to discover for each time of life, not only the passive but the active principle. Now the active principle is particularly lively in this great organ of sense, the child. Thus a child lives in its environment in the manner in which, in later years our eye dwells in its environment. Our eye is especially formed from out the general organisation of the head. It lies, that is, in a cavity apart, so that it can participate in the life of the outer world. In the same way the child participates in the life of the outer world, lives entirely within the external world—does not yet feel itself—but lives entirely in the outer world. We develop nowadays a form of knowledge, called intellectual knowledge, which is entirely within us. It is the form of knowledge appropriate to our civilisation. We believe that we can comprehend the outer world, but the thoughts and the logic to which alone we grant cognitive value dwell within ourselves. And a child lives entirely outside of himself. Have we the right to believe that with our intellectual mode of knowledge we can ever participate in that experience of the outer world which the child has?—the child who is all sense-organ? This we cannot do. This we can only hope to achieve by a cognition which can go right out of itself, which can enter into the nature of all that lives and moves. Intuitional cognition is the only cognition which can do this. Not intellectual knowledge which leaves us within ourselves; which makes us ask of every idea: is it logical? No, but a knowledge by means of which the spirit penetrates into the depths of life itself—intuitional knowledge. We must consciously acquire an intuitional knowledge, then only shall we be practical enough to do with spirit what has to be accomplished with the child in his earliest years. Now, as the child gradually accomplishes the changing of teeth, when in place of the inherited teeth there appear those which have been formed during the first period of life (1-7)—there comes about a change in the child's whole life. Now no longer is he entirely sense-organ, but he is given up to a more psychical element than that of the sense impressions. The child of primary school age now no longer absorbs what he observes in his surroundings, but rather that which lives in what he observes. The child enters upon the stage which must be based mainly on the principle of authority, the authority a child meets with in his educators or teachers. Do not let us deceive ourselves into thinking that a child between seven and fourteen, whom we are educating, does not adopt from us the judgments we give expression to. If we compel a child to listen to a judgment expressed in a certain phrase, we are giving him something which rightly belongs only to a later age. What the true nature of the child demands of us is to be able to believe in us, to have the instinctive feeling: ‘Here stands one beside me who tells me something. He can tell things because he is so connected with the whole world that he can tell. For me he is the mediator between myself and the whole universe. This is how the child confronts his teacher and educator—not of course outspokenly but instinctively. For the child the adult is the mediator between the divine world and himself in his helplessness. And only when the educator is conscious that he must be such an authority as a matter of course, that he must be such as the child can look up to in a perfectly natural way, can he be a true educator. Hence we have found in the course of our Waldorf School teaching and our Waldorf School education that the question of education is principally a question of teachers. What must the teacher: be like in order to be a natural authority, the mediator between the divine order of the world and the child? Well, what has the child become? Between the 7th and 14th or 15th year from being sense-organ the child has become all soul. Not spirit as yet—not such that he sets the highest value on logical connections, on intellect; this would cause inner ossification in his soul. It is far more significant for a child between seven and fourteen years to tell him about a thing in a kindly, loving way, than to demonstrate by proof. Kindly humour and geniality in a lesson have far more value than logic. For the child does not yet need logic. For the child does not yet need logic. The child needs us, needs our humanity. Hence in the Waldorf School we set the greatest importance on the teachers of children from seven to fourteen years being able to give them what is appropriate to their age with artistic love and loving art. For it is fundamental to the education of which we are speaking that one should know the human being, that one should know what each age demands of us in respect of education and instruction. What is demanded by the first year? What is demanded up to the seventh year? What is required of the primary school period? The way of educating children up to the tenth year must be quite different, and different again must be the way we introduce them to human knowledge between 10 and 14. To have in our souls a lively image of the child's nature in every single year, nay, in every single week,—this constitutes the spiritual basis of education. Thus we can say: As the child is an imitator, a ‘copy-cat’ in his early years, so, in his later years he becomes a follower, one who develops in his soul according to what he is able in his psychic environment to experience in soul. The sense organs have now become independent. The soul of the child has actually only just come into its own. We must now treat this soul with infinite tenderness. As teacher and educator we must come into continually more intimate contact with what is happening day by day in the child's soul. In this introductory talk to-day I will indicate only one thing. There is, namely, for every child a critical point during the age of school attendance; roughly between the 9th and 11th year there is a critical moment, a moment which must not be over-looked by the teacher. In this age between the 9th and 11th year there comes for every child—if he is not abnormal—the moment when he says to himself: ‘How can I find my place within the world?’ One must not suppose that the question is put just as I have said it. The question arises in indefinite feelings, in unsatisfied feelings. The question shows itself in the child's having a longing for dependence on a grown-up person. Perhaps it will take the form of a great love and attachment felt for some grown-up person. But we must understand how rightly to observe what is happening in the child at this critical time. The child suddenly finds himself isolated. He seeks something to hold on to. Up till now he has accepted authority as a matter of course. Now he begins to ask: What is this authority? Our finding or not finding the right word to say at this moment will make an enormous difference to the whole of the child's later life. It is enormously important that the physician observing a childish illness should say to himself: What is going on in the organism are processes of development which are not significant only for the child—if they do not go rightly in the child the man will suffer the effects when he is old. Similarly must we realise that the ideas, sensations or will impulses we give the child must not be formulated in stiff concepts which the child has only to heed and learn: the ideas, the impulses and sensations which we give the child must be alive as our limbs are alive. The child's hand is small. It must grow of its own accord, we may not constrain it. The ideas, the psychic development of the child are small and delicate, we must not confine them within hard limits as if we assumed that the child must retain them in thirty years' time when grown-up—in the same form as in childhood. We must so form the ideas we bring the child that they can grow. The Waldorf School does not aim at being a school, but a preparatory school; for every school should be a preparatory school to the great school of manhood, which is life itself. We must not learn at school for the sake of performance, but we must learn at school in order to be able to learn further from life. Such must be the basis of what may be called a spiritual physiological pedagogy and didactics. One must have a sense and feeling for bringing to the child living things that can continue with him into later life. For that which is fostered in a child often dwells in the depths of the child's soul imperceptibly. In later life it comes out. One can make use of an image—it is only by way of image, but it rests upon a truth: There are people who at a certain time of their lives have a beneficent influence upon their fellow men. They can—if I may use the expression—bestow blessing. There are such people,—they do not need to speak, they only need to be there with their personality which blesses. The whole course of a man's life is usually not observed, otherwise notice would be taken of the upbringing of such people—of people like this who later have the power of blessing; it may have been the conscious deed of some one person, or it may have been unconscious on the part of teacher and educator:—Such people have been brought up as children to learn reverence, to learn, in the most comprehensive meaning of the word, to pray—to look up to something;—and hence they could will down to something. If one has learned at first to look up, to honour, to be entirely surrounded by authority, then one has the possibility to bless, to work down, oneself to become an authority, an unquestioned authority. These are the things which must not merely live as precepts in the teacher, but must pass into him, become part of his being—going from his head continuously into his arms. So that a man can do deeds with his spirit, not merely think thoughts. These things must come to life in the teacher. In the next few days I will show how this can come about in detail throughout each single year of school life between seven, and fourteen. But before all things I wanted to explain to-day how a certain manner of inner life, not merely an outlook on life but an inner attitude must form the basis of education. Then, when the child has outgrown the stage of authority, when he has attained puberty and through this has physio-logically quite a different connection with the outer world than before, he also attains in soul and body (in his bodily life in its most comprehensive sense) a quite different relation-ship to the world than he had earlier. This is the time of the awakening of Spirit in Man. This now is the time when the human being seeks out the rational and logical aspect in all verbal expression. Only now can we hope to appeal with any success to the intellect in our education and instruction. It is immensely important that we do not consciously or unconsciously call upon the intellect prematurely, as people are so prone to do to-day. And now let us ask ourselves: What is happening when we observe how the child takes on authority, everything that is to guide and lead his soul. For a child does not listen to us in order to check and prove what we say. Unconsciously the child takes up as an inspiration what works upon his soul, what, through his soul, builds and influences his body. And we can only rightly educate when we understand the wonderful, unconscious inspiration, which holds sway in the whole life of a child between seven and fourteen, when we can work into the continuous process of inspiration. To do this we' must acquire still another power of spiritual cognition, we must add to Intuition, Inspiration itself. And when we have led the child on its way as far as the 14th year we make a peculiar discovery. If we attempt to give the child things that we have conceived logically—we become wearisome to him. To begin with he will listen, when we thus formulate every-thing in a logical way; but if the young man or maiden must re-think our logic after us, he will gradually become weary. Also in this period we, as teachers need something besides pure logic. This can be seen from a general example. Take a scientist such as Ernst Haeckel who lived entirely in external nature. He was himself tremendously interested in all his microscopic studies, in all he built up. If this is taught to pupils, they learn it but they cannot develop the same interest for it. We as teachers must develop something different from what the child has in himself. If the child is coming into the domain of logic at the age of puberty, we (in our turn) must develop imagery, imagination. If we ourselves can pour into picture form the subjects we have to give the children, if we can give them pictures, so that they receive images of the world and the work and meaning of the world, pictures which we create for them, as in a high form of art—then they will be held by what we have to tell them. So that in this third period of life we are directed to Imagination, as in the other two to Intuition and Inspiration. And we now have to seek for the spiritual basis which can make it possible for us as teachers to work from out of Imagination, Inspiration and Intuition—which can make it possible not merely to think of spirit, but to act with spirit. This is what I wished to say to you by way of introduction. |

| 305. Spiritual Ground of Education: Spiritual Disciplines of Yesterday: Yoga

17 Aug 1922, Oxford Translated by Daphne Harwood Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| I have been informed that there was something difficult to understand in what I spoke about yesterday. In particular that difficulties had arisen from my use of the words “Spiritual” and “spiritual cognition.” |

| Mind, Intellect, is copy, reflection, passivity itself:—that thing within us which enables us, when we are older, to understand the world. If intellect, if mind were active we should not be able to understand the world. Mind has to be passive so that the world may be understood through it. |

| Thus he came to experience how in the brain, breath unites with the material process which under-lies thinking, which underlies intellectual activity. He searched into this union between thinking and breathing and finally experienced how thought, which is for us an abstract thing, pervades the whole body on the tide of the breath. |

| 305. Spiritual Ground of Education: Spiritual Disciplines of Yesterday: Yoga

17 Aug 1922, Oxford Translated by Daphne Harwood Rudolf Steiner |

|---|