| 291. Colour: The Hierarchies and the Nature of the Rainbow

04 Jan 1924, Dornach Translated by Harry Collison Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| Light is what distinguishes the paths of these Beings. Under certain circumstances when light appears somewhere, there also appears shadow, darkness, dark shadow. |

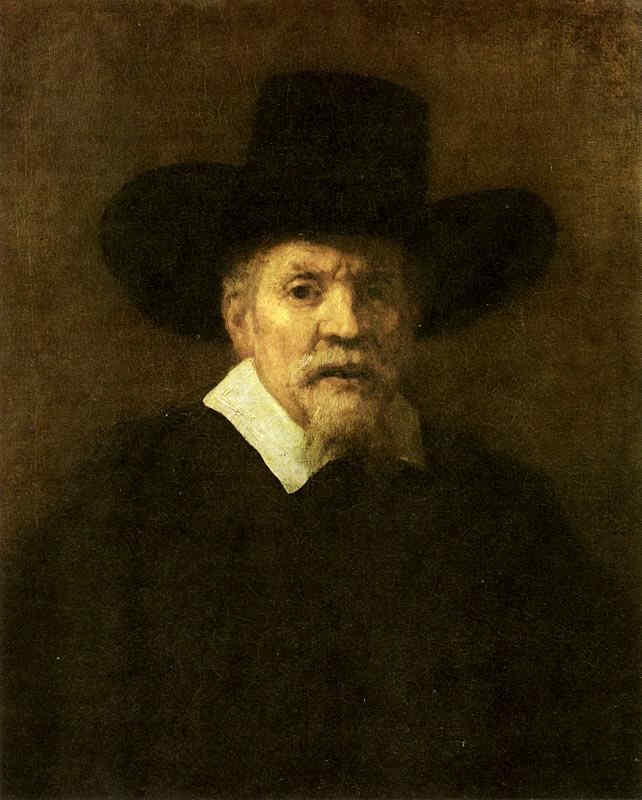

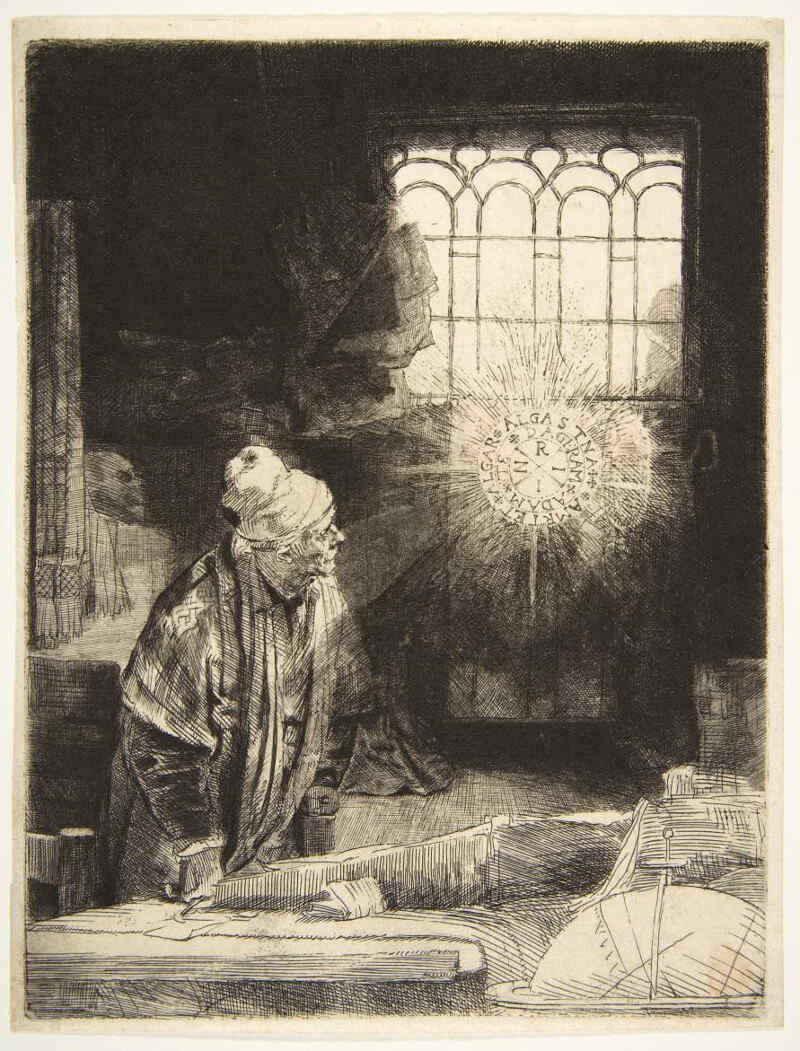

| One can say that in approaching the learned men of the eleventh, twelfth and thirteenth centuries, one must understand such things in this way. You cannot understand Albertus Magnus if you read him with modern knowledge, you must read him with the knowledge that such spiritual things were a reality to him and then only will you understand the meaning of his words and expressions. |

| What is this Fourth Hierarchy? It is man himself. But formerly one did not understand by it the remarkably odd being with two legs and the tendency to decay that wanders about the world now; for then the human being of the present day appeared to the scholar as an unusual kind of being. |

| 291. Colour: The Hierarchies and the Nature of the Rainbow

04 Jan 1924, Dornach Translated by Harry Collison Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

When I wrote my Occult Science, I was compelled to bring the evolution of the earth somewhat into line with present-day ideas. In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries one could have put it differently. For instance, in a certain chapter of this Occult Science the following might then have been found. One would have spoken otherwise of those beings whom one can describe as the beings of the first hierarchy: Seraphim, Cherubim, Thrones. One would have called the Seraphim those beings who make no differentiation between subject and object, who would not say: there are objects outside myself, but: the world is, and I am the world and the world is I—who know of their own existence only by means of an experience, of which man has a weak idea when some experience carries him away in glowing rapture. It is in fact sometimes difficult to explain to modern people what a glowing rapture is, for it was even understood better at the beginning of the nineteenth century than it is now. It still happened then that some poem or other, by this or that poet, was read, and the people acted through rapture—forgive my saying so, but it was so—as if they were mad! So much were they moved, so much were they suffused with warmth. Nowadays people are frozen just when one thinks they should be enraptured. And this rapture of the soul—which was experienced particularly in Central and Eastern Europe,—if raised as a unifying element into the consciousness gives one an idea of the inner life of the Seraphim. And we have to imagine the consciousness-element of the Cherubim as a completely purified element in the consciousness, full of light, so that thought becomes directly light, and illumines everything; and the element of the Thrones as bearing up the world in grace. One would then have said: the choir of Seraphim, Cherubim and Thrones act together, in such a way that the thrones constitute a nucleus, and the Cherubim radiate their own luminous nature from it. The Seraphim cover the whole in a mantle of rapture, which streams out into all space. But these are all beings: in the midst of the Thrones, round them the Cherubim, and in the periphery, the Seraphim. They are beings which mutually interplay and act and think and will and feel. And if a being possessing the necessary susceptibility had traveled through space where the thrones and Cherubim and Seraphim had thus formed a center, he would have felt warmth in different degrees and in different places; now higher, now lower warmth, but yet in a spiritual and psychic way; in such a way, however, that the psychic experience is at the same time a physical experience in our senses. Thus, when the being feels the warmth psychically, there really is present what you feel when you are in a heated room. Such a union of the begins of the First Hierarchy did exist once upon a time in the universe. And this formed the system and existence of the “Saturnian Age.” Warmth is just the expression of these beings. The warmth is nothing in itself, it is only the evidence that these beings exist. I should like to use a simile here which may perhaps help as an explanation. Suppose you are fond of somebody, you find his presence warms you. Suppose further there comes another man who has no heart at all and says: that person doesn't interest me in the least; I am interested only in the warmth which he spreads around. He does not say he is interested in the warmth the other sheds, but that nothing but the warmth interests him. He is talking nonsense, of course, for when the person who radiates warmth has gone, the warmth has gone also. It is there only when the person is there. In itself it is nothing. The person must be there for the warmth to be there. Thus Seraphim, Cherubim and Thrones must be there; otherwise warmth is not there either. It is merely the revelation of the Seraphim, Cherubim and Thrones. Now at the time of which I speak, what I have just described to you did in actual fact exist. When one spoke of the element of warmth one was understood to mean really Cherubim, Seraphim and Thrones. That was the Saturnian Age. Then one went further and said that only this highest hierarchy, the Seraphim, Cherubim and Thrones, has the might and the power to produce something of this kind in the Cosmos. And only by reason of the fact that this was done at the beginning of a terrestrial creation could evolution proceed. The Sun, as it were, of the Seraphim, Cherubim and Thrones was able to a certain extent to direct the course of it. And this happened in such a way that the Beings produced by the Seraphim, Cherubim and Thrones, the Beings of the Second Hierarchy—the Kyriotetes, Exusiai and Dynamis—now surged into this space created and warmed in this Saturnian life by the Seraphim, Cherubim and Thrones. Thus the younger—of course, the cosmically younger—Beings entered in; and theirs was the next influence. Whereas the Seraphim, Cherubim and Thrones revealed themselves in the element of warmth, the Beings of the Second Hierarchy were seen in the element of light. The Saturnian element is dark, but warm, and within the dark and gloomy world of the Saturnian existence arises light, precisely the thing that can appear through the sons of the Second Hierarchy , through the Exusiai, Dynamis and Kyriotetes. This is the case because the entry of the Second Hierarchy represents an inward illumination, which is connected with a densification of warmth. Air comes forth from the pure warmth-element, and in the revelation of the light we have the entry of the Second Hierarchy. But you must get this clear: Actually Beings press in. Light is present for a Being with the necessary powers of perception. Light is what distinguishes the paths of these Beings. Under certain circumstances when light appears somewhere, there also appears shadow, darkness, dark shadow. So shadow also arose through the entry of the Second Hierarchy in the form of light. What was this shadow? The air. And actually till the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries it was known what the air is. Today one knows only that the air consists of oxygen and nitrogen, etc. which means no more than if one says, for instance, that a watch is made of glass and silver—whereby nothing whatever is said about the watch. Similarly nothing whatever is said about the air as a cosmic phenomenon when you say it consists of oxygen and nitrogen. But a great deal is said if one knows that from the cosmic point of view air is the shadow of the light. So that with the entry of the Second Hierarchy into the Saturnian warmth, one actually has in fact the entry of light, and its shadow, air. And where that happens is Sun. In the thirteenth and twelfth centuries one would really have had to talk in this manner. The further stages of development are now conducted by the sons of the Third Hierarchy, the Archai, Archangels and Angels. These Beings bring into the luminous element with its shadow of air, introduced by the Second Hierarchy, another element resembling our desire, our urge to acquire something, our longing to have something. Hence it came about that, let us say, an Archai or Archangel-Being entered and found an element of light, or rather, a place of light. In this place it felt, by reason of its sensitiveness to light, the urge towards and desire for darkness. The Angel-Being carried the light into the darkness, or an Angel-Being carried the darkness into the light. These Beings became the intermediaries, the messengers between light and darkness. The result was that what formerly shone only in light, an trailed behind it, its shadow, the somber, airy darkness, now began to gleam in all colours, that light appeared in darkness, and darkness in light. It was the Third Hierarchy which conjured forth colour from out of light and darkness. Observe, you have here something as it were historically documented to put before your souls. In the time of Aristotle one still knew—supposing one had pondered within the Mysteries on the origin of colours—that the Beings of the Third Hierarchy had to do with this. Wherefore Aristotle expressed in his Colour-Harmony that colour was a combined effect of Light and Darkness. But this spiritual element was lost—that the First Hierarchy was responsible for warmth, the Second for light and its shadow, the air, and the Third or the shining forth of colour in a world continuity. And there remained nothing but the unfortunate Newtonian theory of Colour, over which the initiated have smiled up to the eighteenth century, and which then became an article of faith with those who were just expert physicists. In order to speak in the sense of this Newtonian theory, it is really necessary for one to have no knowledge at all of the spiritual world. And if one is still inwardly spurred by the spiritual world, as was the case with Goethe, one is utterly opposed to it. One states what is correct as Goethe did, then one storms dreadfully. Goethe was never so furious as on the occasion when he castigated Newton; he was simply furious about the wretched nonsense. We cannot understand such things today, simply because anyone who does not recognize the Newtonian teaching concerning colour is looked upon by the physicists as a fool. But it was not really the case that Goethe stood quite alone in his own time. He alone uttered these things, but even at the end of the eighteenth century the learned knew perfectly well that the origin of colour lay in the spiritual world. Air is the shadow of light. Just as when light radiates and, under certain circumstances, gives rise to deep shadow, so, if colour is present, and this colour works as a reality in the airy element, not merely as a reflection, not merely as a reflex-colour, but as a Reality; then the fluid, watery element arises from out of the real colour element. As air is the shadow of light, in cosmic thought, so water is the reflection, the creation of the element of colour in the Cosmos. You will say you don't understand this. But just try to grasp the real meaning of colour. Red—well—do you believe that red in its real nature is only the neutral surface on generally regards it? Surely Red is something which attacks one. I have often discussed it. Red makes one want to run away; it pushes one back. Violet-blue one wants to pursue; it continually evades one, and gets ever darker and darker. Everything lives in colours. They are a world of their own, and the psychic element feels in the colour-world the necessity for movement, if it follows colours with psychic experience. Today man stares at the rainbow. If one looks at it with the slightest imagination, one sees elemental beings active in it. They are revealed in remarkable phenomena. In the yellow certain of them are seen continually emerging from the rainbow, and moving across to the green. The moment they reach the underneath of the green, they are attracted to and disappear in it, to emerge on the other side. The whole rainbow reveals to an imaginative observer an outpouring and a disappearance of the spiritual. It reveals in fact something like a spiritual waltz. At the same time one notices that as these spiritual beings emerge in red-yellow, they do it with an extraordinary apprehension; and as they enter into the blue-violet, they do it with an unconquerable courage. When you look at the red-yellow, you see streams of fear, and when you look at the blue-violet you have the feeling that there is the seat of all courage and valor. Now imagine we have the rainbow in section. Then these being emerge in the red-yellow and disappear in the blue-violet; here apprehension, here courage, which disappears again. There the rainbow becomes dense and you can imagine the watery element arises from it. Spiritual beings exist in this watery element which are really a kind of copy of the beings of the Third Hierarchy. One can say that in approaching the learned men of the eleventh, twelfth and thirteenth centuries, one must understand such things in this way. You cannot understand Albertus Magnus if you read him with modern knowledge, you must read him with the knowledge that such spiritual things were a reality to him and then only will you understand the meaning of his words and expressions. In this way therefore air and water appear as a reflection of the Hierarchies. The Second Hierarchy enters in the form of light, the Third in the form of colour. But in order to enable this to be established, the lunar existence is created. And now comes the Fourth Hierarchy. I am speaking now with the thought of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Now the Fourth Hierarchy. We never speak of it; but in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries one spoke freely of it. What is this Fourth Hierarchy? It is man himself. But formerly one did not understand by it the remarkably odd being with two legs and the tendency to decay that wanders about the world now; for then the human being of the present day appeared to the scholar as an unusual kind of being. They spoke of primeval man before the Fall, who existed in such a form as to have as much power over the earth as Angeloi, Archangeloi and so on, had over the lunar existence; the Second Hierarchy over the solar existence; the First Hierarchy over the Saturnian existence. They spoke of man in his original terrestrial existence, and as the Fourth Hierarchy. And with this Fourth Hierarchy came—as a gift form the higher Hierarchies of something they first possessed, and preserved, and did not themselves require—Life. And life came into the colourful world which I have been sketchily describing to you. You will ask—But didn't things live before this? The answer you can learn from man himself. Your ego and your astral body have not life, but they exist all the same. The spiritual, the soul, does not require life. Life begins only with your etheric body; and this is something in the nature of an outer wrapping. It is thus that life appears only after the lunar existence, with the terrestrial existence, in that stage of evolution which belongs to our earth. The iridescent world became alive. It is not only then that Angeloi, Archangeloi, etc., felt a desire to bring light into darkness and darkness into light and so called forth the play of colours in the planets, but also they desired to experience this play of colour inwardly, and make it inward; to feel weakness and lassitude when darkness inwardly dominates over light, and activity when light dominates over darkness. For what happens when you r un? When you run it means that light dominates over the darkness in you; when you sit and are idle, the reverse happens. It is the effect of colour in the soul, the effect of colour iridescence. The iridescence of colour, permeated and shot with life, appeared with the coming of man, the Fourth Hierarchy. And at this moment of cosmic growth the forces which became active in the iridescence of colour began to form outlines. Life, which rounded off, smoothed and shaped the colours, called forth the hard crystal form; and we are in the terrestrial epoch. Such things as I have now explained to you were really the axioms of those medieval alchemists, occultists, Rosicrucians, etc., who, though scarcely mentioned today in history, flourished from the ninth and tenth up to the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, and whose stragglers, always regarded as oddities, existed into the eighteenth century and even into the beginning of the nineteenth. Only then were these things entirely covered up. The philosophical attitude to life of the time led to the following phenomenon: Suppose I have here a human being. I cease to have any interest in him, merely take off his clothes and hang them on a clothes-dummy with a knob at the top like a head, and thereafter take no more interest in the human being. I say to myself further: That is the human being, what does it matter to me that anything can be put into these clothes; the dummy is, as far as I am concerned, the human being. So it was with the elements of Nature. People are no longer interested that behind warmth of fire is the First Hierarchy, behind light and air is the Second, behind the so-called chemical ether, colour-ether, etc. and water is the Third, behind life and the earth is the Fourth, or Man. Out with the clothes-horse and hang the clothes on it! That is the first Act. The second begins then with the school of Kant!~ Here begins Kantianism, here one begins, having the clothes-horse with the clothes on it, to philosophize concerning what “the thing in itself” of these clothes might be. And the conclusion is that one cannot recognize “the thing in itself” of the clothes. Very perspicacious! Naturally, if you have removed the man first, you can philosophize about the clothes, and this leads to a very pretty speculation: the clothes-horse is there all right, and the clothes hanging on it, so one speculates either in the Kantian fashion—one cannot recognize “the thing in itself”—or in the manner of Helmholtz, saying: these clothes cannot surely have form. There must be crowds of tiny whirling specks of dust, or atoms, in them, which by their movement preserve the clothes in their form. Yes, this is the turn that later thought has taken. But it is abstract, and shadowy. All the same it is the kind of thought in which we live today; out of it we fashion the whole of our Natural Scientific principles. And when we deny that we think in terms of atoms, we are doing it all the more. For it will be a long time before it is admitted that it is unnecessary to weave a Dance of the Atoms into it, rather than simply to replace man into his clothes. But that is just what the resuscitation of Spiritual Science must attempt. |

| 291. Titian's “Assumption of Mary”

09 Jun 1923, Dornach Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| A world emerges all by itself. Because if you understand color, then you understand an ingredient of the whole world. You see, Kant once said: Give me matter, and I will create a world out of it. |

| If Mary were down there, for example, one would not understand the purpose. If she were sitting among the apostles, yes, she could not look as she does in the middle between heaven and earth. |

| And if you accept that there is a relationship to the spiritual from the artistic point of view, you will understand that the artistic is something through which one can enter the spiritual world, both in creating and in enjoying. |

| 291. Titian's “Assumption of Mary”

09 Jun 1923, Dornach Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

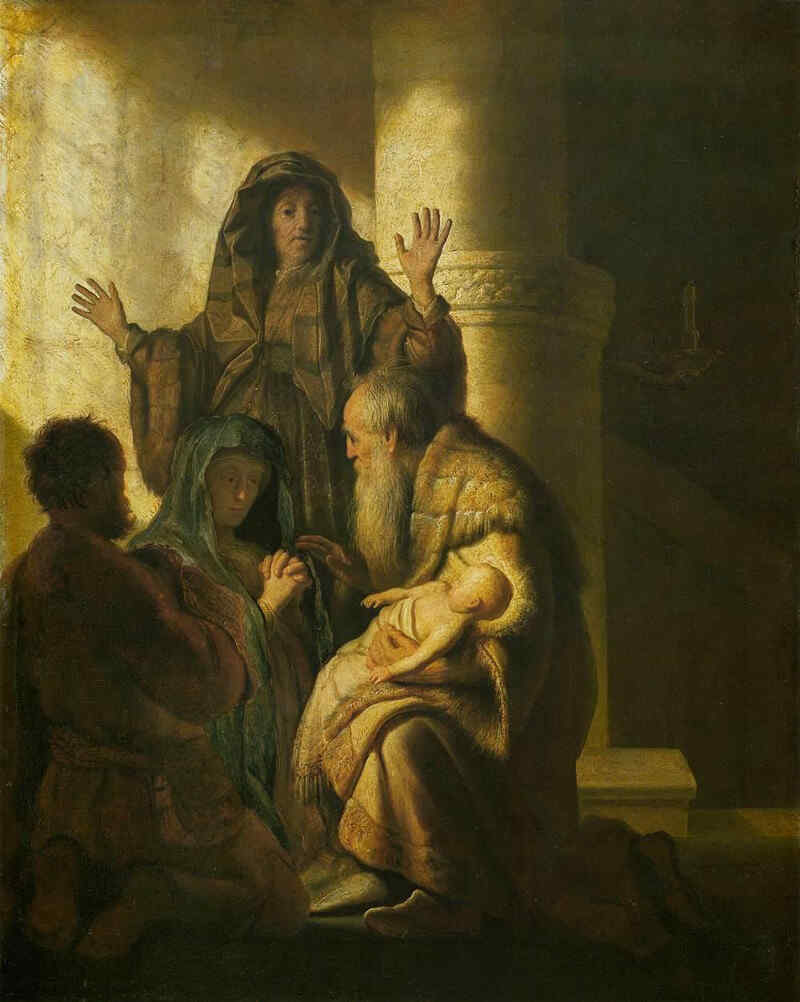

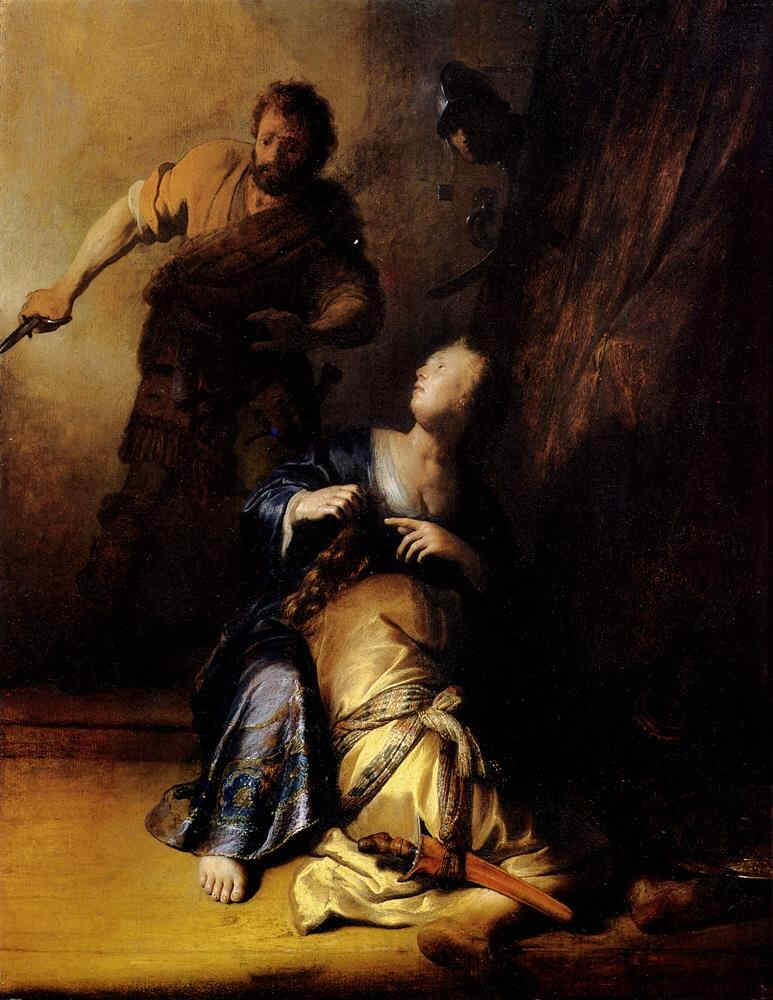

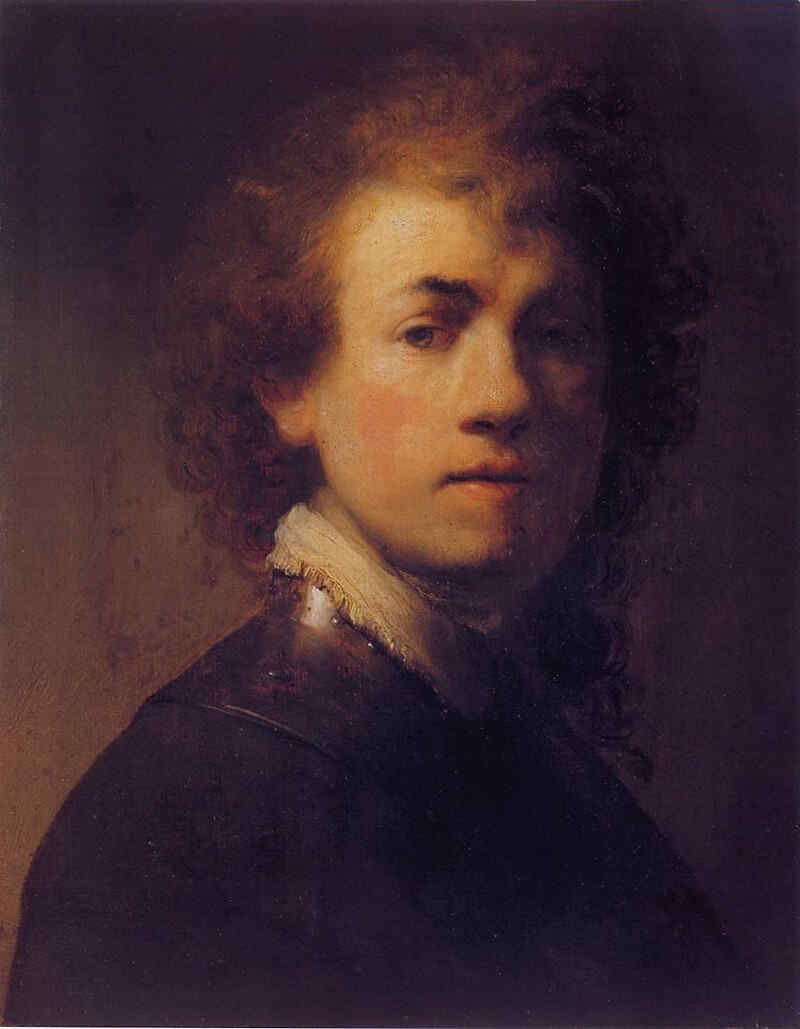

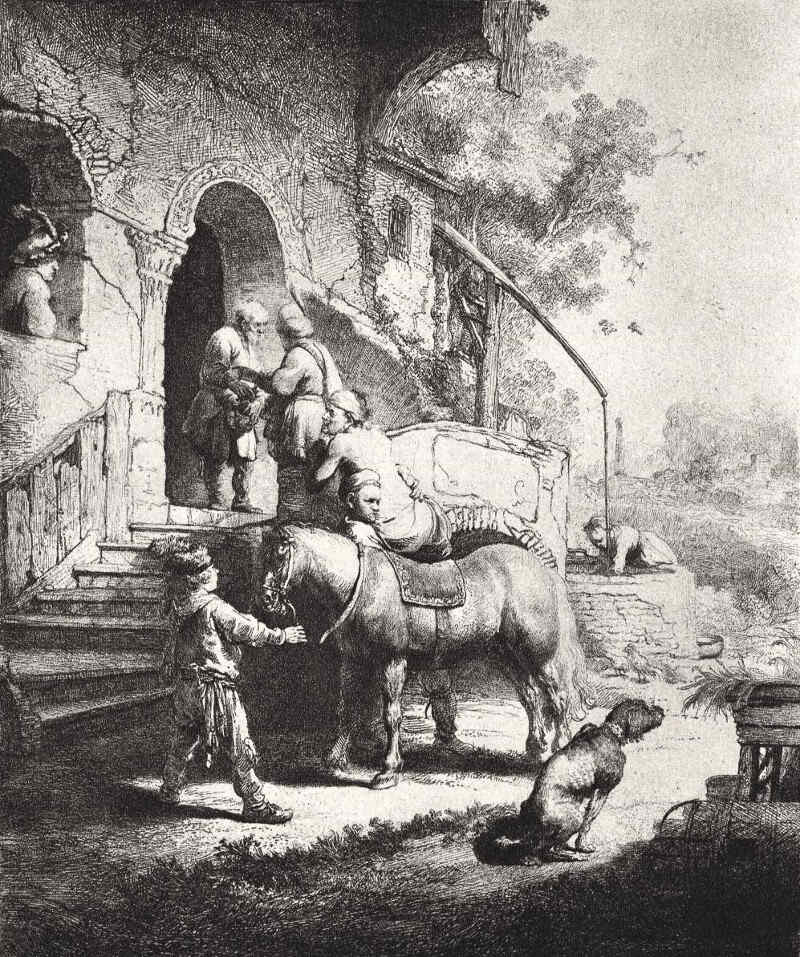

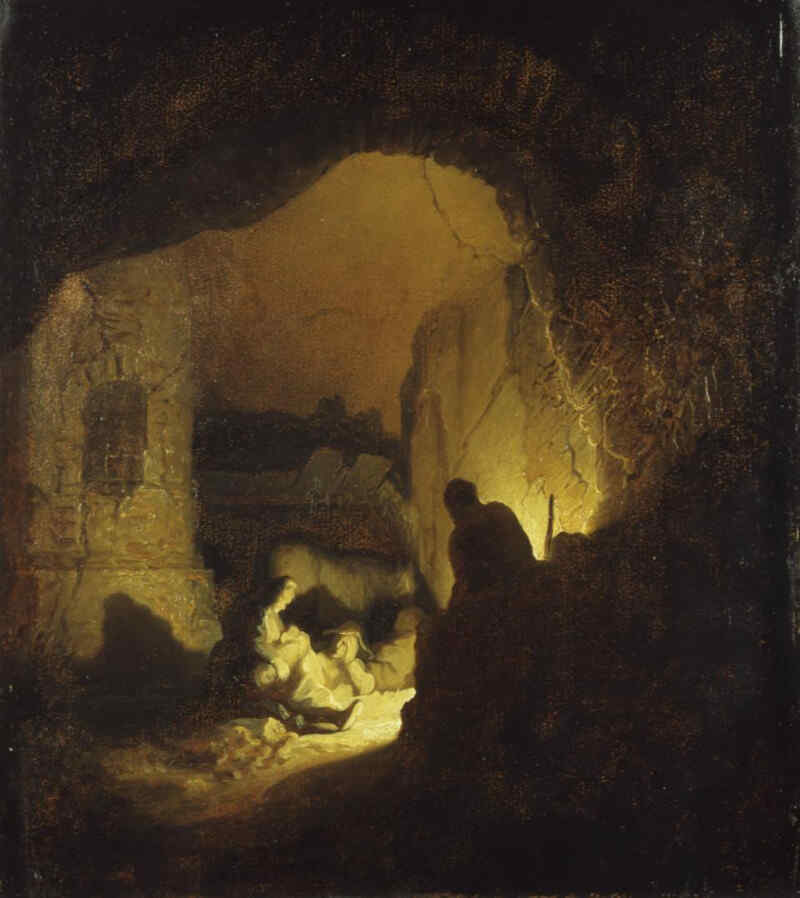

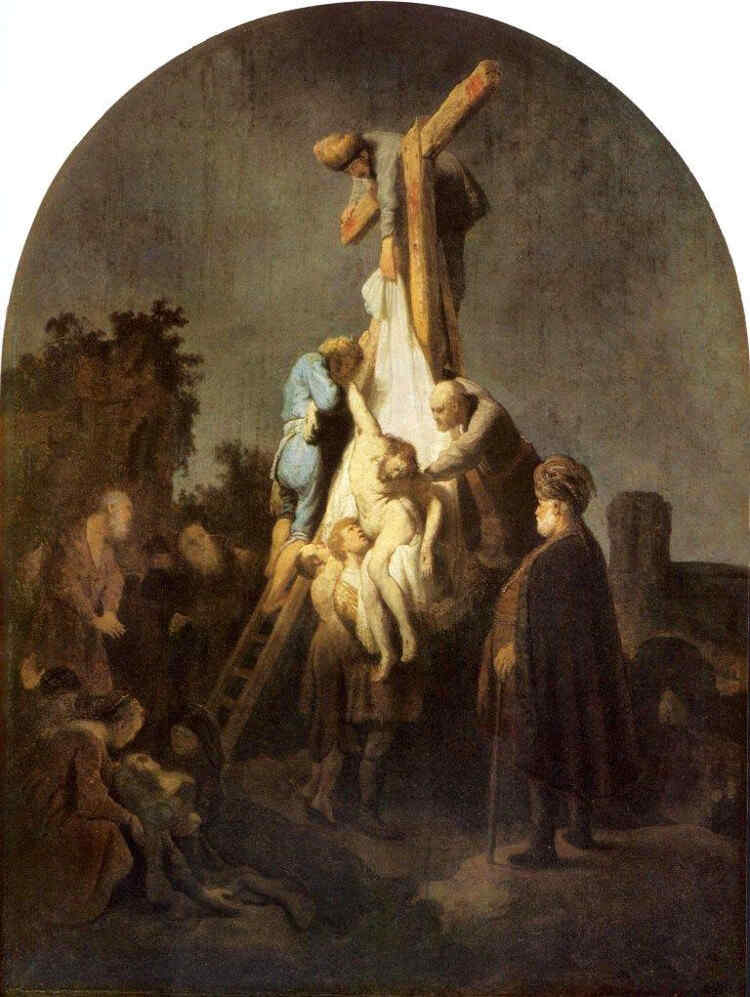

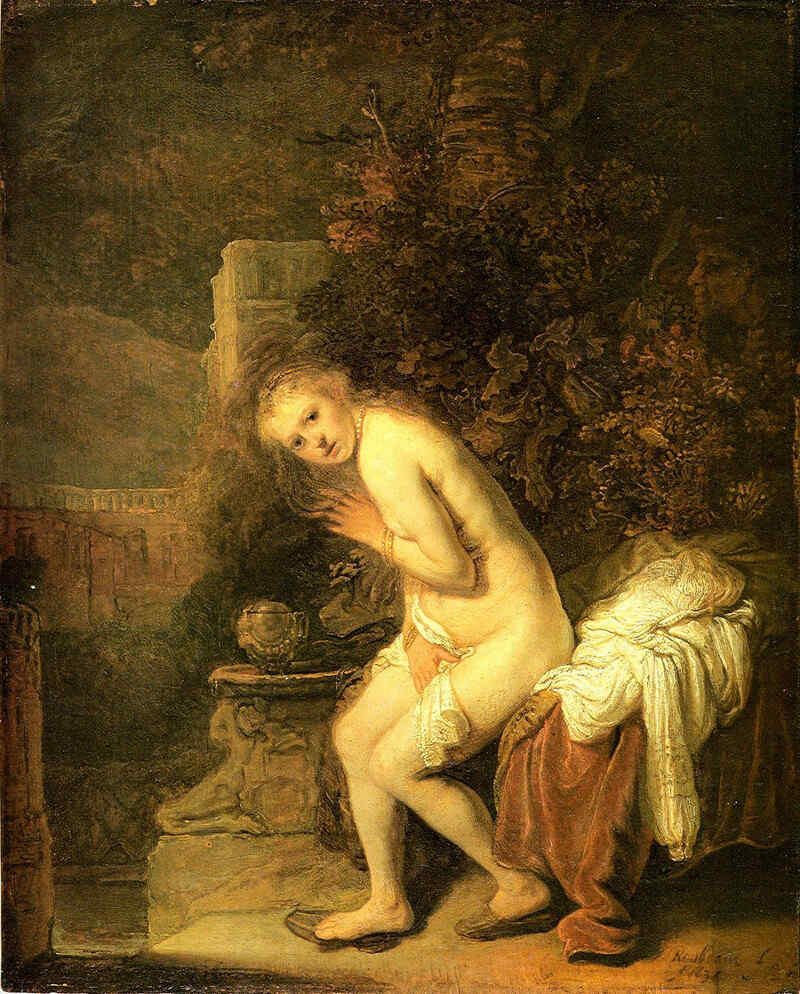

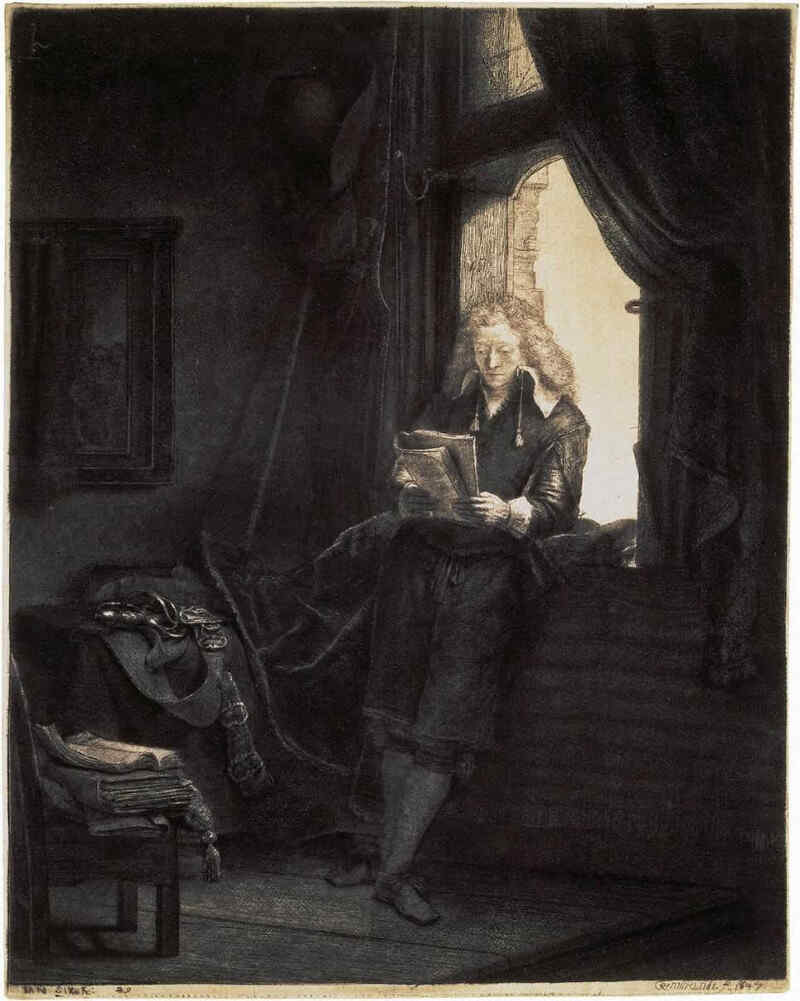

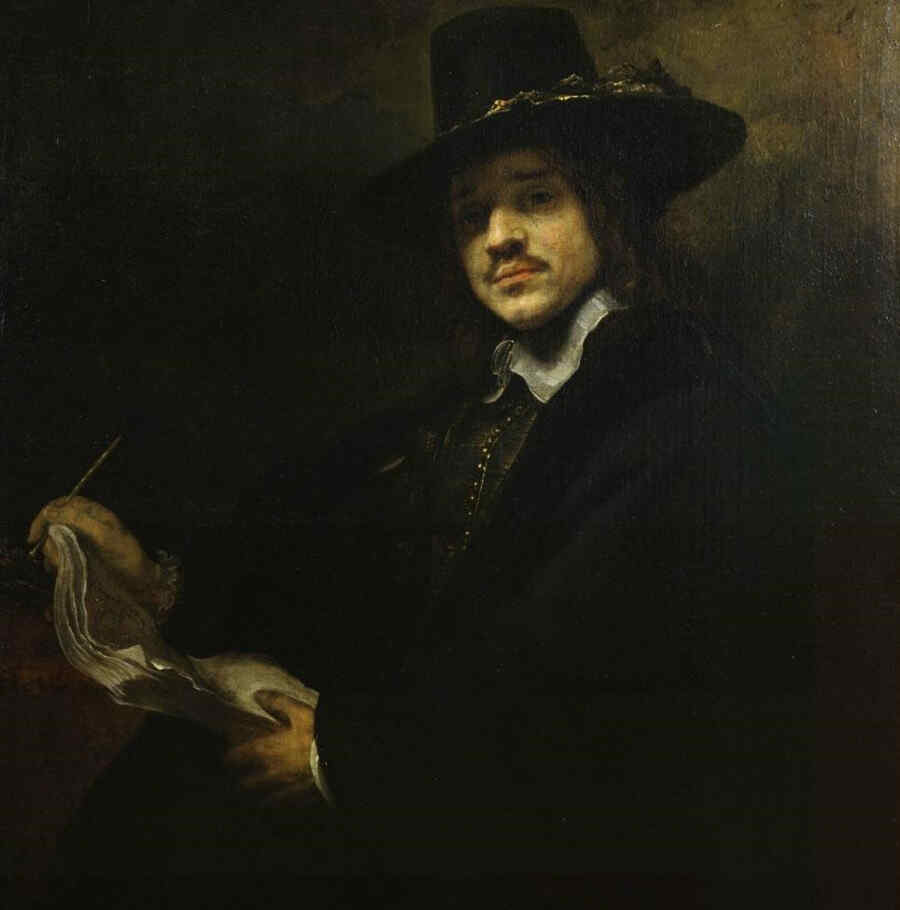

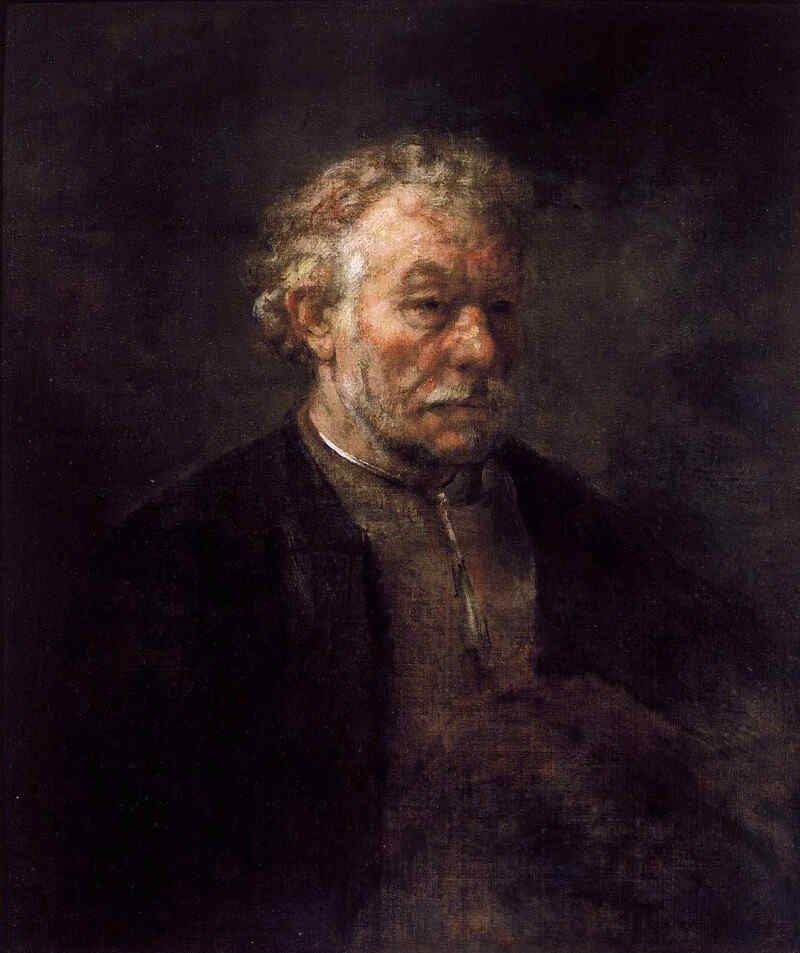

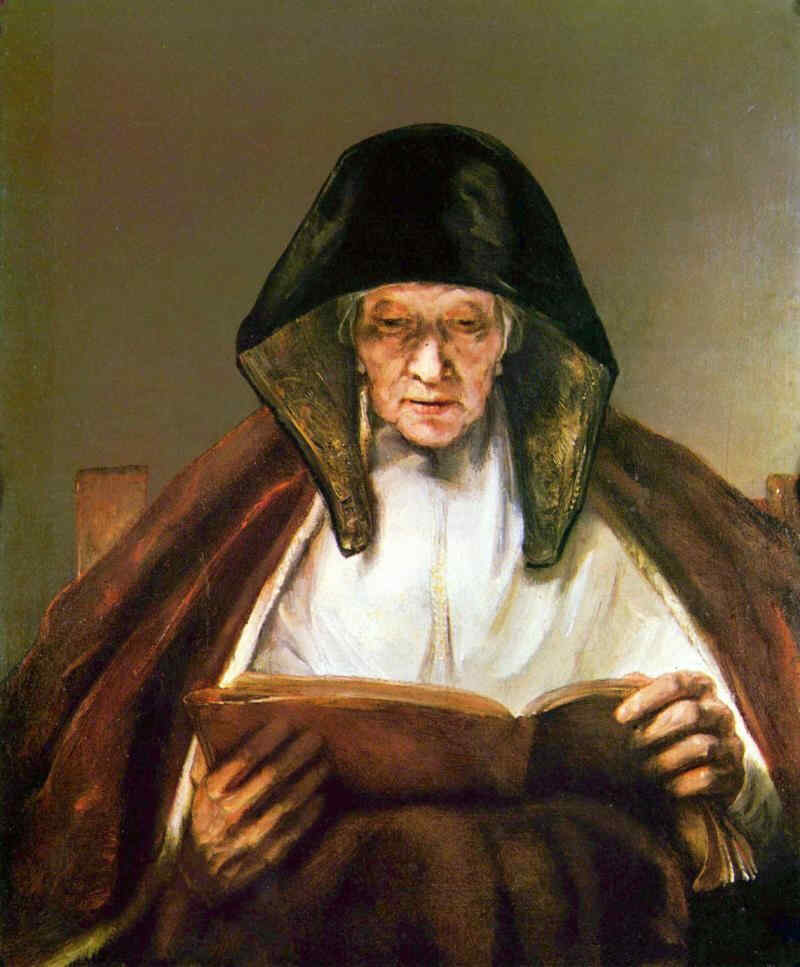

Today I would like to add a few words to the lectures I have given here in the last few days. In earlier lectures I often spoke of a genius of language. And you already know from my book 'Theosophy' how, when spiritual essence is spoken of in the anthroposophical context, real spiritual essence is meant, and so also in what is referred to as the genius of language, real spiritual essence for the individual languages is meant, into which man lives and which, as it were, gives him the strength from the spiritual worlds to express his thoughts, which initially exist as a dead inheritance of the spiritual world in him as an earthly being. Therefore, it is particularly appropriate in the anthroposophical context to seek a meaning in what appears as formations in language, a meaning that even comes from the spiritual worlds to a certain extent independently of man. Now, I have already pointed out the peculiar way in which we describe the actual element of the artistic, of beauty, and its opposite. We speak of the beautiful and speak of its opposite in the individual languages, of the ugly. If we were to describe the beautiful in a way that is entirely appropriate to the ugly, then, since the opposite of hate is love, we would have to speak not of the beautiful, but of the lovely. We would then have to say the lovely, that ugly. But we speak of the beautiful and the ugly and, based on the genius of language, make a significant distinction by designating the one and its opposite in this way. The beautiful, if we take it in the German language for the moment – a similar one would have to be found for other languages – is related as a word to that which shines. That which is beautiful shines, that is, carries its inner being to the surface. That is the essence of beauty: it does not hide, but brings its inner being to the surface, to the outer form. So that what is beautiful is that which reveals its inner being in its outer form, that which shines, that which radiates light, so that the light reveals what radiates out into the world, the essence. If we want to speak of the opposite of beauty in this sense, we have to say: that which hides itself, that which does not shine, that which withholds its essence and does not reveal to the outside world in its outer shell what it is. So when we speak of beauty, we are describing something objectively. If we were to speak just as objectively about the opposite of beauty, we would have to describe it with a word that means “that which hides itself, that which appears outwardly as other than it is.” But here we depart from the objective and approach the subjective, and then we describe our relationship to that which hides itself, and we find that we cannot love that which hides itself, we must hate it. That which shows us a different face than it is is the opposite of beauty. But we do not describe it, so to speak, from the same background of our being; we describe it from our emotion as that which is hateful to us because it hides itself, because it does not reveal itself. If we listen carefully to language, then the genius of language can reveal itself to us. And we must ask ourselves: What are we actually striving for when we strive for the beautiful, in the broadest sense, through art? What are we actually striving for? The mere fact that we have to choose a word for the beautiful that comes from us, from the genius of language – for the opposite we do not go out of ourselves, we remain within ourselves, remain with our emotions, with hatred – the mere fact that we have to go out of ourselves shows that in the beautiful there is a relationship to the spiritual that is outside of us. For what seems? That which we see with our senses does not need to shine for us, it is there. That which shines for us, that is, which radiates in the sensual and announces its essence in the sensual, is the spiritual. So, when we speak objectively of the beautiful as beautiful, we grasp the artistically beautiful from the outset as a spiritual that reveals itself through art in the world. It is the task of art to grasp what appears, the radiance, the revelation of that which, as spirit, permeates and lives through the world. And all real art seeks the spiritual. Even when art, as it may, wants to depict the ugly, the repulsive, it does not want to depict the sensual repulsive, but the spiritual that announces its essence in the sensual repulsive. The ugly can become beautiful when the spiritual reveals itself in the ugly. But it must be so, the relationship to the spiritual must always be there if an artistic work is to have a beautiful effect. Now, let us look at a single art form from this point of view, let us say painting. We have considered it in the last few days, in so far as painting reveals the spiritual essence through the color grasped, that is, through the radiance of the color. One may say that in those times when one had a real inner knowledge of color, one also surrendered to the genius of speech in the right way in order to place color in a worldly relationship. If you go back to ancient times, when there was an instinctive clairvoyance for these things, you will find, for example, metals that were felt to reveal their inner essence in their color, but were not named after earthly things. There is a connection between the names of the metals and the planets, because, if I may put it this way, people would have been ashamed to describe what is expressed through color only as an earthly thing. In this sense, color was regarded as a divine-spiritual element that is only conferred on earthly things in the sense in which I explained it here a few days ago. When gold was perceived in the color of gold, then one saw in gold not only an earthly thing, but one saw in the color of gold the sun announcing itself from the cosmos. Thus one saw in advance something going beyond the earth, even when perceiving the color of an earthly thing. Only by going up to the living things, one attributed their own color to the living things, because the living things approach the spirit, so there spiritual is also allowed to shine. And with the animals one felt that they have their own colors, because spiritual-soul in them appears directly. But now you can go back to older times, when people felt artistically not outwardly but inwardly. You see, you don't get any painting at all. It's almost foolish to say, to paint a tree green, to paint a tree – to paint a tree and paint it green, that is not painting; because it is not painting for the very reason that whatever one accomplishes in imitating nature, nature is always more beautiful, more essential. Nature is always more full of life. There is no reason to imitate what is out there in nature. But then, real painters don't do that either. Real painters use the object to, let's say, make the sun shine on it, or to observe some color reflection from the surroundings, to capture the interweaving and interlacing of light and dark over an object. So the object you paint is actually only ever the reason for doing so. Of course you never paint, say, a flower that is standing in front of the window, but you paint the light that shines in through the window and that you see in the same way as you see it through the flower. So you actually paint the colored light of the sun. You capture that. And the flower is only the reason for capturing that light. When you approach the human being, you can do it even more spiritually. Taking a human forehead and painting it like a human forehead – as you believe you see a human forehead – is actually nonsense, it is not painting. But how a human forehead is exposed to the sun's rays as they fall, how a dull light appears in the highlight, how the chiaroscuro plays – all that, in other words, that the subject provides the occasion for, that passes in the moment, and that one must now relate to a spiritual, to capture with color and brush, that is the task of the painter. If you have a sense of painting, when you see an interior, for example, it is not at all about looking at the person kneeling in front of an altar. I once visited an exhibition with someone. We saw a person kneeling in front of an altar. You saw him from behind. The painter had set himself the task of capturing the sunlight streaming in through a window just as it would fall on the man's back. Yes, the man who was with me to look at the picture said: I would prefer to see the man from the front! Yes, that's right, there is only a material, not an artistic interest. He wanted the painter to express what kind of person it is and so on. But you are only entitled to do that if you want to express what can be perceived through color. If I want to depict a person on a hospital bed, in a particular illness, and I study the color of the face in order to capture the appearance of the illness through the senses, then that can be artistic. If I also want to depict, let's say, in totality, to what extent the whole cosmos comes to expression in human incarnate, in human flesh color, that can also be artistic. But if I were to imitate Mr. Lehmann, as he sits there in front of me, firstly I wouldn't succeed, would I, and secondly it's not an artistic task. What is artistic is the way the sun shines on him, how the light is deflected by his bushy eyebrows. So that's what matters, how the whole world affects the being I paint. And the means by which I achieve this is chiaroscuro, is color, is capturing a moment that is actually passing and fixing it in the way I described yesterday. In times not so far removed from our own, people felt these things very keenly, as they could not imagine representing a Mary, a Mother of God, without a transfigured face, that is, without a face overwhelmed by the light and which emerges from the ordinary human condition through the overwhelming of the light. She could not be depicted in any other way than in a red robe and a blue mantle, because only in this way is the Mother of God placed in the right way in earthly life: in the red robe with all the emotions of the earthly, , the soul in the blue cloak, which envelops her with the spiritual, and in the transfigured face, the spiritualized, which is overwhelmed by the light as the revelation of the spirit. But this is not grasped in a truly artistic way as long as one only feels it as I have just expressed it. I have now, so to speak, translated it into the inartistic. One only feels it artistically in the moment when one creates out of the red and out of the blue and out of the light, by experiencing the light in its relationship to the colors and to the darkness as a world unto itself, so that one actually has nothing but the color, and the color says so much that one can get out of the color and the light-dark the Virgin Mary. But then you have to know how to live with color, color has to be something you live with. Color has to be something that has emancipated itself from the heavy material. Because the heavy material actually resists color if you want to use it artistically. That is why it goes against the whole idea of painting to work with palette colors. They always become so that they still show a heaviness when you have applied them to the surface. You can't live with the palette color either. You can only live with liquid color. And in the life that develops between the person and the color when he has the color liquid, and in the peculiar relationship that he has when he now applies the liquid color to the surface, a color life develops, one actually grasps from out of the color, the world is grasped out of the color. Only then does the picturesque emerge, when you grasp the radiance, the revelation, the radiance of the color as a living thing, and only then do you actually create the shape on the surface from the radiating life. A world emerges all by itself. Because if you understand color, then you understand an ingredient of the whole world. You see, Kant once said: Give me matter, and I will create a world out of it. Well, you could have given it to him long ago, the matter, you can be quite sure that he would not have made a world out of it, because no world can be created out of matter. But more can be created out of the undulating tools of colors. A world can be created from them, because every color has its immediate, I would say personal and intimate relationship to some spiritual aspect of the world. And today, with the exception of the primitive beginnings made in Impressionism and so on, and especially in Expressionism, but these are just beginnings, the concept of painting, the activity of painting, has been more or less lost to us in the face of the general materialism of the time. For the most part today, one does not paint, but rather one imitates shapes by means of a kind of drawing and then paints the surface. But these are painted surfaces, they are not painted, they are not born out of color and light and dark. But one must not misunderstand the matter. If someone goes wild and simply tinkers with the colors next to each other, believing that he is achieving what I have called overcoming drawing, then he is not at all achieving what I meant. For by overcoming the drawing I do not mean having no drawing, but to get the drawing out of the color, to give birth to it out of the color. And the color already gives the drawing, one must only know how to live in the color. This living in the colored then leads the real artist to be able to disregard the rest of the world and give birth to his works of art out of the colored. You can go back, for example, to Titian's “Assumption of Mary”. There you have a work of art that, I might say, consists of the transgression of the old principles of art. There is no longer the living experience of color that one still has with Raphael, but especially with Leonardo; but there is still a kind of tradition present that prevents one from growing too strongly out of this life in color. Experience this “Assumption of Mary” by Titian. When you look at it, you can see that the green cries out, the red cries out, the blue cries out. Yes, but then look at the individual colors. If you take the interaction of the individual colors even in Titian, you still have an idea of how he lived in the colors and how he really gets all three worlds out of the colors in this case. Just look at the wonderful gradation of the three worlds. Below are the apostles who experience the event of the Assumption of Mary. Look at how he manages to capture them in color. You can see how they are bound to the earth in the colors, but you don't feel the heaviness of the colors; instead, you only feel the darkness of the colors at the bottom of Titian's painting, and in the darkness you experience the apostles' being tied to the earth. In the way Mary is treated in color, you experience the intermediate realm. She is still connected to the earth. If you have the opportunity, look at the picture and see how the dull darkness from below is incorporated as a color in the coloring of Mary, and how then the light predominates, how the uppermost, the third realm already receives in full light, I would like to say, the head of Mary, shining with full light, lifting up the head, while the feet and legs are still bound down by the color. Observe how the lower realm, the intermediate realm and the heavenly realm, this reception of Mary by God the Father, is truly gradated in the inner experience of color. You can say that in order to understand this picture, one must actually forget everything else and look only at the color, because the three-tiered nature of the world is brought out of the color here, not conceptually, not intellectually, but entirely artistically. And one can say: It is really the case that, in order to grasp the world in a painterly way, it is necessary to grasp this world of radiant shine, of radiant revelation in chiaroscuro and in color, in order to emphasize, on the one hand, what is earthly-material, to emphasize the artistic aspect of this earthly-material aspect, and yet, on the other hand, not to let it rise to the spiritual. For if it were allowed to reach the spiritual plane, it would no longer be appearance, but wisdom. But wisdom is no longer artistic; wisdom lifts it up into the uncreated realm of the divine. One would therefore like to say: In the case of the real artist, who depicts something like Titian in his “Assumption of Mary”, when one looks at this reception of Mary, or rather of Mary's head by God the Father, one has the feeling that one should no longer go further in the treatment of the light. It is a very fine line. The moment you start going further, you fall into intellectualism, which is unartistic. You can no longer add a line, I might say, to what is only hinted at in the light, not in the contour. Because the moment you go too far into the contour, it becomes intellectualized, that is, inartistic. Towards the top, the picture is in fact in danger of being inartistic. Painters after Titian also fell prey to this danger. Look at the angels up to Titian. When we go up to the heavenly region, we come to the angels. Look at how carefully the transition from color is avoided. You can still say that the angels in the pre-Titian period, and in a sense in Titian, are just clouds. If you cannot do that, if you cannot distinguish between being and appearance, even in the uncertainty, when you have already fully arrived at the being, at the being of the spiritual, then it ceases to be artistic. If you go back to the 17th century, it will be different. There, materialism itself is already having an effect on the representation of the spiritual. There you can already see all the angels, I might say, painted with a certain non-artistic, but routine verve in all possible foreshortenings, to which you can no longer say: Couldn't they also be clouds? Yes, here reflection is already at work, here the artistic aspect already comes to an end. And again, look at the apostles below, and you will get the feeling that, in fact, only Mary is artistic in the “Ascension of Mary”. Above, there is a danger that it turns into pure wisdom, into the formless. If one really achieves this, holding the formless and making it formless, then, I would say, on one side, towards one pole, there is the perfection of the artistic, because it is boldly artistic, because one ventures to the abyss where art ends, where one lets the colors blur from the light, where, if one wanted to go further, one could only begin to draw. But drawing is not painting. So there, towards the top, one approaches the realm of wisdom. And one is all the greater an artist the more one can still incorporate the wisdom into the sensual, the more one, if I want to express myself in concrete terms again, the more one can still incorporate the wisdom into the sensual, the more one, if I want to express myself in concrete terms again, the more one can still incorporate the possibility that the angels one paints can still be addressed as concentrated clouds that shimmer in the light in such and such a way and the like. But if we start at the bottom of the picture and go up through the actual beauty, Mary herself, who is really floating up into the realm of wisdom, then Titian is able to depict her beautifully because she has not yet arrived, but is just floating up. It all appears in such a way that one has the feeling that if she swings up a little more, she will have to enter into wisdom. Art has nothing more to say there. But if we go down a little further, we come to the Apostles, and with the Apostles I said to you: the artist seeks to depict the earthly aspect of the Apostles through the use of color. But there he runs into the other danger. If he were to place his Mary even further down, he would not be able to depict her in her inner, self-sustaining beauty. If Mary were down there, for example, one would not understand the purpose. If she were sitting among the apostles, yes, she could not look as she does in the middle between heaven and earth. She could not look at all like that. You see, the apostles are standing below in their brownish coloration, and Mary does not fit in with them. For we cannot really stop at the fact that the apostles below have the heaviness of the earth in them. Something else must happen. This is where the element of drawing begins to intervene strongly. You can see this in Titian's characterized painting, where drawing begins to intervene strongly. Why is that? Yes, you can no longer depict beauty in the brown, which actually goes beyond color, as you can in the case of Mary; something that no longer falls entirely within beauty must be depicted. And it must be beautiful in that something other than what is actually beautiful is revealed. You see, if Mary were sitting down there or standing among these apostles in the same coloring, it would actually be insulting. It would be terribly insulting. I am speaking only of this picture. I am not saying that Mary standing on the earth must be artistically offensive everywhere, but in this picture it would be a slap in the face for anyone looking at it artistically if Mary were standing down there. Why? You see, if she were painted in the same colors as the apostles, one would have to say that Mary was portrayed by the artist as virtuous. That is indeed how he portrays the apostles. We cannot have any other idea than that the apostles are looking up in their virtue. But we cannot say that about Mary. With her, it is so self-evident that we must not express her virtue. It would be just as if we wanted to depict God as virtuous. Where something is self-evident, where it becomes something that is being itself, it must not be depicted merely in outward appearance. Therefore, Mary must float away, must be in a realm where she is exalted above the virtuous, where one cannot say of her, in what appears in the color, that she is virtuous, any more than one could say of God himself that he is virtuous. At most, he can be virtue itself. But that is already an abstract sentence, that is already philosophy. It has nothing to do with art. But in the apostles below, we have to say that the artist succeeds in depicting the virtuous people through the color treatment itself in the apostles. They are virtuous. Let us again try to get close to the matter through the genius of language. Virtue, what does it actually mean to be virtuous? To be virtuous is to be useful; because virtue is related to being useful. To be useful, to be useful, to be good for something, that is to be up to something, to be able to do something, to be able to do something, that is to be virtuous. But of course it ultimately depends on what one means in connection with virtuous, as for example Goethe also presented it, who speaks of a trinity: wisdom, appearance and power, that is, in this sense, virtuousness. Appearance = the beautiful, art. Wisdom = that which becomes knowledge, formless knowledge. Virtue, power = that which is truly useful, that which can do something, whose rule means something. You see, this trinity has been revered since time immemorial. I could understand when a man told me a good many years ago that he was already sick of it when people spoke of the true, the beautiful and the good, because everyone who wants to say a phrase, an idealistic phrase, speaks of the true, the beautiful and the good. — But one can refer back to older times when these things were experienced with all human interest, with all human soul interest. And then, I would like to say, one sees, but in the manner of the beautiful, of the artistic, in the Titian painting above, wisdom, but not just wisdom, but still shining, so that it is still artistic, so that it is painted; in the middle, beauty; and below, virtue, the useful. Now we may ask the useful a little about its inner essence, its meaning. If we follow these things, we come, through the genius of speech, to the depth of the speech soul that creates among human beings. If we approach it only externally, it might occur to us that someone who had once been to church and listened to a sermon, where the preacher explained to his congregation in an outwardly phrase-like way how everything in the world is good and beautiful and purposeful. The adult was waiting at the church door and when the pastor came out, he asked him: “You said that everything in the world is good and beautiful and purposeful according to your idea. Am I also growing well?” The pastor said: “You have grown very well for an adult!” — Well, if you look at things in this external way, you won't get to the depths of them. Our way of looking at things today is in fact so superficial in so many fields. People today fill themselves completely with such external characteristics, namely with such external definitions, and do not even realize how they go around in circles with their ideas. For the virtuous person, it is not about being good at anything at all, but about being good at something spiritual, about placing ourselves in the spiritual world as human beings. The truly virtuous person is the one who is a whole human being because he brings the spiritual within him to realization, not just to manifestation, to realization through the will. But then we enter a region that, although it is human, also enters the religious, but no longer lies in the realm of the artistic, least of all in the realm of the beautiful. Everything in the world is formed in polarity. Therefore, we can say of Titian's painting: at the top he exposes himself to the danger of going beyond the beautiful, where he goes beyond Mary. There he is at the abyss of wisdom. Downwards, he is at the other abyss. For as soon as we depict the virtuous, that which man, as a being of his own essence, is meant to realize out of the spiritual, we in turn come out of the beautiful, out of the artistic. If we try to paint a truly virtuous person, we can only do so by somehow characterizing virtue in outward appearance, for my part by contrasting it with vice. But the artistic portrayal of virtue no longer actually shows any art; in our time it is already a falling out of the artistic. But where is not everywhere in our time a falling out of the artistic, when, I would like to say, simply life circumstances are reproduced in a raw, naturalistic way, without the relationship to the spiritual really being there. Without this relationship to the spiritual, there is no artistry. Therefore, in our time, this striving in Impressionism and Expressionism is to return to the spiritual. Even if it is often done awkwardly, even if it is often only a beginning, it is still more than that which works with the model in a crude naturalistic way, which is inartistic. And if you grasp the concept of the artistically beautiful in this way, then you will also be able to accommodate tragedy, for example, and grasp tragedy in general in its artistic reach into the world. A person who lives according to his thoughts, who leads his life in an intellectualistic way, can never become tragic. And a person who lives a completely virtuous life can never truly become tragic either. A person can become tragic if they have some kind of inclination towards the demonic, that is, towards the spiritual. A personality, a person, only begins to become tragic when the demonic is present in him in some way, for better or for worse. Now we are in the age of the freeing of the human being, where the human being as a demonic human being is actually an anachronism. That is the whole meaning of the fifth post-Atlantean period, that the human being grows out of the demonic to become a free human being. But as the human being becomes a free human being, the possibility of the tragic, so to speak, ceases. If you take the old tragic figures, even most of Shakespeare's tragic figures, you have the inner demonic that leads to the tragic. Wherever man is the manifestation of a demonic-spiritual, wherever the demonic-spiritual radiates through him, reveals itself, wherever man becomes, as it were, the medium of the demonic, there the tragic was possible. In this sense, the tragic will have to cease more or less, because humanity, having been set free, must break away from the demonic. Today it does not yet do so. It is falling ever deeper into the demonic. But this is the great task for our time, the mission of our time, that human beings grow out of the demonic and into freedom. But if we get rid of the inner demons that shape us into tragic personalities, we will be all the less able to get rid of the external demonic. For the moment man enters into a relationship with the external world, something demonic also begins for the modern human being. Our thoughts must become ever freer and freer. And when, as I have shown in my Philosophy of Freedom, thoughts become the impulses for the will, the will also becomes free. These are the polar opposites that can be set free: free thoughts and free will. But in between lies the rest of humanity, which is connected with karma. And just as the demonic once led to tragedy, so too can the experience of karma lead to a deep inner tragedy, especially in modern man. But tragedy will only be able to flourish when people experience karma. As long as we keep our thoughts to ourselves, we can be free. When we clothe our thoughts in words, the words no longer belong to us. What can become of a word that I have spoken! It is taken up by the other person, who surrounds it with different emotions and different feelings. The word lives on. As the word flies through the people of the present, it becomes a force that originated from a person. That is its karma, through which it is connected to the world, which in turn can be discharged back onto it. The word, which leads its own existence because it does not belong to us, because it belongs to the genius of language, can cause tragedy. Today, in particular, we see humanity, I would say, everywhere in the disposition to tragic situations through the overestimation of language, through the overestimation of the word. The peoples are divided according to language, want to be divided according to language. This is the basis for a huge tragedy that will befall the earth before the century is out. This is the tragedy of karma. If we can speak of the tragedy of the past as a tragedy of demonology, we must speak of the tragedy of the future as the tragedy of karma. Art is eternal; its forms change. And if you accept that there is a relationship to the spiritual from the artistic point of view, you will understand that the artistic is something through which one can enter the spiritual world, both in creating and in enjoying. A true artist can create his picture in a lonely desert. It makes no difference to him who looks at the picture, or whether anyone looks at it at all, because he has created in a different community, he has created in the divine spiritual community. Gods have looked over his shoulders. He has created in the company of gods. What does it matter to the true artist whether any human being admires his picture or not? That is why one can be an artist in complete solitude. But on the other hand, one cannot be an artist without really placing one's own creature in the world, which one then also regards in terms of its spirituality, so that it lives in it. The creature that one places in the world must live in the spirituality of the world. If one forgets this spiritual connection, then art also changes, but it changes more or less into non-art. You see, you can only create art if you have the work of art in the context of the world. The old artists were aware of this, who, for example, painted their pictures on the walls of churches, because there these pictures were guides for the believers, for the confessors, there the artists knew that this is in the earthly life, insofar as this earthly life is permeated by the spiritual. It is hard to imagine something worse than creating for exhibitions instead of for such a purpose. Basically, it is the most terrible thing to walk through a painting exhibition or a sculpture exhibition, for example, where all kinds of things are hung or placed next to each other in a chaotic manner, where they don't belong together at all, where it is actually meaningless that one is next to the other. By painting having found the transition from painting for the church, for the house, to painting, I would like to say, already there, it loses its proper meaning. If you paint something within the frame, you can at least imagine looking out through a window and what you see is outside, but it is no longer anything. But now painting for exhibitions! You can't talk about it anymore. Isn't it true that a time that sees anything at all in exhibitions, sees anything possible, has just lost the connection with art. And you can see simply from what intellectual culture has to happen in order to find the way back to the intellectual-artistic. The exhibition, for example, can certainly be overcome. Of course, individual artists feel disgust for the exhibition, but we live in a time when the individual cannot achieve much unless the judgment of the individual is immersed in a worldview that in turn people in their freedom, in full freedom, as worldviews once permeated people in less free times and led to the emergence of real cultures, while today we have no real cultures. However, a spiritual worldview must work on the development of real cultures and thus also on the development of real art, and have the highest interest in doing so. |

| 292. The History of Art I: Cimabue, Giotto, and Other Italian Masters

08 Oct 1916, Dornach Translator Unknown Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| First you will see some picture by Cimabue. Under this name there go, or, rather, used to go—a number of pictures, church paintings, springing from a conception of life altogether remote from our own. |

| Strangely enough, this discussion went on into the time when in the West, under the influence of Rome, men had already lost the faculty to represent real beauty—a faculty which they had still possessed in former centuries under the more immediate influence of Greece. |

| The birds are his brothers and his sisters; the stars, the sun, the moon, the little worm that crawls over the Earth—all are his brothers and his sisters; on all of them he looks with loving sympathy and understanding. Going along his way he picks up the little worm and puts it on one side so as not to tread it underfoot. |

| 292. The History of Art I: Cimabue, Giotto, and Other Italian Masters

08 Oct 1916, Dornach Translator Unknown Rudolf Steiner |

|---|