| 74. The Redemption of Thinking (1956): Lecture II

23 May 1920, Dornach Translated by Alan P. Shepherd, Mildred Robertson Nicoll Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| 74. The Redemption of Thinking (1956): Lecture II

23 May 1920, Dornach Translated by Alan P. Shepherd, Mildred Robertson Nicoll Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

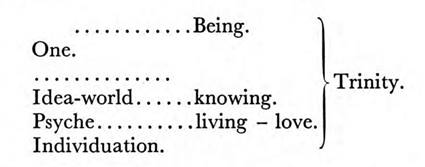

What I especially tried to stress yesterday was that in that spiritual development of the West which found its expression in scholasticism not only that happens which one can grasp in abstractions and which took place in a development of abstractions, but that behind it a real development of the impulses of western humanity exists. I think that one can look at that at first, as one does mostly in the history of philosophy, which one finds with the single philosophers. One can pursue, how the ideas, which one finds with a personality of the sixth, seventh, eighth, ninth centuries, are continued by personalities of the tenth, eleventh, twelfth, thirteenth centuries, and one can get the impression by such a consideration that one thinker took over certain ideas from the other and that a certain evolution of ideas is there. One has to leave this historical consideration of the spiritual life gradually. Since that which manifests from the single human souls are only symptoms of deeper events which are behind the scene of the outer processes. These events which happened already a few centuries before Christianity was founded until the time of scholasticism is a quite organic process in the development of western humanity. Without looking at this process, it is equally impossible to get information about that development, we say from the twelfth until the twentieth years of a human being unless one considers the important impact in this age that is associated with sexual maturity and all forces that work their way up from the subsoil of the human being. Thus, something works its way up from the depths of this big organism of European humanity that one can just characterise saying: those old poets spoke very honestly and sincerely who began their epic poems as Homer did: sing to me, goddess, on the rage of the Peleid Achilles—, or: sing to me, muse, on the actions of the widely wandered man.—These men wanted to say no commonplace phrase, they felt as inner fact of their consciousness that not a single individual ego wants to express itself there but a higher spiritual-mental that intervenes in the usual state of human consciousness. Again—I said it already yesterday—Klopstock was sincere and figured this fact out in a way, even if maybe only instinctively, when he began his Messiah; now not: sing, muse, or: sing, goddess, on the redemption of the human beings -, but he said: sing, immortal soul -, that means: sing, individual being that lives in the single person as an individuality.—When Klopstock wrote his Messiah, this individual feeling had already advanced far in the single souls. However, this inner desire to stress individuality originated especially in the age of the foundation of Christianity until High Scholasticism. In that which the philosophers thought one can notice the uppermost, which goes up to the extreme surface of that which takes place in the depths of humanity: the individualisation of the European consciousness. An essential moment of the propagation of Christianity in these centuries is the fact that the missionaries had to speak to people who more and more strove for feeling the inner individuality. Only from this viewpoint, you can understand the conflicts that took place in the souls of such human beings who wanted to deal with Christianity on one side and with philosophy on the other side as Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas did. Today the common histories of philosophy describe the soul conflicts too little, which found their end in Albert and Thomas. There many things intervened in the soul life of Albert and Thomas. Seen from without it seems, as if Albert the Great who lived from the twelfth to the thirteenth century and Thomas who lived in the thirteenth century wanted to combine Augustinism and Aristotelianism only dialectically on one side. The one of them was the bearer of the ecclesiastical ideas; the other was the bearer of the cultivated philosophical ideas. You can pursue their searching for the harmony of both views everywhere in their writings. Nevertheless, in everything that is fixed there in thoughts endlessly much lives that did not pass to that age which extends from the middle of the fifteenth century until our days, and from which we take our common ideas for all sciences and also for the whole public life. It appears to the modern human, actually, only as something paradox: the fact that Augustine really thought that a part of the human beings is destined from the start to receive the divine grace without merit—for they all would have to perish because of the original sin—and to be saved mental-spiritually. The other part of humanity must perish mental-spiritually, whatever it undertakes.—For the modern human being this seems paradox, maybe even pointless. Someone who can empathise in the age of Augustine in which he received those ideas and sensations that I have characterised yesterday will feel different. He will feel that one can understand that Augustine wanted still to adhere to the ideas that not yet cared about the single person that just cared about the general-human influenced by such ideas as those of Plotinism. However, on the other side, the drive for individuality stirred in the soul of Augustine. Hence, these ideas get such a succinct form, hence, they are fulfilled with human experience, and thereby just Augustine makes such a deep impression if we look back at the centuries, which preceded scholasticism. Beyond Augustine that remained for many human beings what the single human being of the West as a Christian held together with his church—but only in the ideas of Augustine. However, these ideas were just not suitable for the western humanity that did not endure the idea to take the whole humanity as a whole and to feel in it like a member, which probably belongs to that part of humanity, which is doomed. Hence, the church needed a way out. Augustine still combated Pelagius (~360-418) intensely, that man who was completely penetrated with the impulse of individuality. He was a contemporary of Augustine; individualism appears in him as usually only the human beings of the later centuries had it. Hence, he could not but say, it can be no talk that the human being must remain quite passive in his destiny in the sensory world. From the human individuality even the power has to originate by which the soul finds the connection to that which raises it from the chains of sensuousness to the pure spiritual regions where it can find its redemption and return to freedom and immortality.—The opponents of Augustine asserted that the single human being must find the power to overcome the original sin. The church stood between both opponents, and it looked for a way out. This way out was often discussed. One talked as it were back and forth, and one decided for the middle. I would like to leave it to you whether it is the golden mean. This middle was the Semipelagianism. One found a formula which announced: indeed, it is in such a way as Augustine said, but, nevertheless, it is not completely in such a way as Augustine said; it is also not completely in such a way as Pelagius said, but it is in a certain sense in such a way as he said. Thus, one can say that, indeed, not by God's everlasting wise decision the ones are destined to sin, the others to grace; but the matter would be in such a way that, indeed, there is no divine predetermination but a divine foreknowledge. God knows in advance whether the one is a sinner or the other is someone who is filled with grace. Besides, we do not take into account when this dogma was spread that it did not at all concern foreknowledge, but that it concerned taking plainly position whether now the single individual human being can combine with the forces in his individual soul life which can cancel his separation from the divine-spiritual being. Thus, the question remains unsolved for dogmatism, and I would like to say, Albert and Thomas were on one side forced to look at the contents of the dogmas of the church, on the other side, however, they were fulfilled with the deepest admiration of the greatness of Augustine. They faced that what was western spiritual development within the Christian current. Nevertheless, still something played a role from former times. It lived on in such a way that one sees it being active on the bottom of their souls, but one also realises that they are not quite aware of it that it has impact in their thoughts that they cannot bring it, however, to an exact version. One must consider this more for this time of High Scholasticism of Albert and Thomas than one would have to consider a similar phenomenon, for example, in our time. I have already emphasised the why and wherefore in my Worldviews and Approaches to Life in the Nineteenth Century. I would only like to note that this book was extended to The Riddles of Philosophy where the concerning passage could not return because the task of the book had changed. We experience that from this struggle of individuality the thinkers who developed this struggle of individuality philosophically reach the zenith of the logical faculty of judgement. One may rail against scholasticism from this or that party viewpoint—all this railing is fulfilled with little expertise as a rule. Since someone who has sense for the way in which the astuteness of thoughts comes about with something that is explained scientifically or different, who has sense to recognise how connections are intellectually combined which must be combined intellectually if life should get sense—who has sense for all that and for some other things already recognises that so exactly, so conscientiously logically one never thought before and after High Scholasticism. Just these are the essentials that the pure thinking proceeds with mathematical security from idea to idea, from judgement to judgement, from conclusion to conclusion in such a way that these thinkers always account to themselves for the smallest step. One has only to mind that this thinking took place in a silent monastic cell or far from the activities of the world. This thinking could still develop the pure technique of thinking by other circumstances. Today it is difficult to develop this pure thinking. Since if one tries anyhow to present such activity to the general public which wants nothing but to string together thoughts, then the biased people, the illogical people come who take up all sorts of things and allege their crude biased opinions. Because one is just a human being among human beings, one has to deal with these things that often are not at all concerned with that which it concerns, actually. One loses that inner quietness very soon to which thinkers of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries could dedicate themselves who did not think much of the contradiction of unprepared people in their social life. This and still some other things caused that wonderful sculptural, on one side, but also in fine contours proceeding activity of thinking which is characteristic for scholasticism and at which Albert and Thomas aimed exceptionally consciously. However, please remember that there are demands of life, on one side, which appear as dogmas which were similarly ambiguous in numerous cases as the characterised Semipelagianism, and that one wanted to maintain the dogmas of the church with the most astute thinking. Imagine only what it means to consider Augustinism just with the most astute thinking. One has to look into the inside of the scholastic striving and not only to characterise the course from the Fathers of the Church to the scholastics along the concepts that one has picked up. Just many semi-conscious things had impact on these spirits of High Scholasticism. You cope with it only if you look beyond that what I have characterised already yesterday and if you still envisage such a figure that entered mysteriously under the name of Dionysius the Areopagite into the European spiritual life from the sixth century on. Today I cannot defer to all disputes about whether his writings were written in the sixth century or whether the other view is right that at least leads back the traditional of these writings to much earlier periods. All that does not matter, but that is the point that the thinkers of the seventh, eighth centuries and still those like Thomas Aquinas studied the views of Dionysius the Areopagite, and that these writings contained that in a special form which I have characterised yesterday as Plotinism, but absolutely with a Christian nuance. That became significant for the Christian thinkers up to High Scholasticism how the writer of Dionysius' writings related to the ascent of the human soul to a view of the divine. One asserts normally that Dionysius had two ways to the divine. Yes, he did have two. One way is that he asks, if the human being wants to ascend from the outside things to the divine, he must find out the essentials of all things which are there, he has to try to go back to the most perfect ones, he must be able to name the most perfect so that he has contents for this most perfect divine which can now pour itself out again as it were and create the single things of the world from itself by individuation and differentiation.—Hence, one would like to say, God is that being to Dionysius that one has to call with many names that one has to give as most distinguishing predicates which one can find out of all perfections of the world. Take any perfection that strikes you in the things of the world, and then call God with it, then you get an idea of God.—This is one way that Dionysius suggests. He says about the other way, you never reach God if you even give him one single name because your endeavour to find the perfections in the things, the essentials of the things, to summarise them to characterise God with. You have to free yourself from everything that you have recognised in the things. You have to purify your consciousness completely from everything that you have found out in the things. You must know nothing of that which the world says to you. You must forget all names that you have given the things and you have to put yourself in a soul condition where you know nothing of the whole world. If you can experience this, you experience the unnamed one who is misjudged immediately if you give him any name; then you recognise God, the super-God in his super-beautifulness. However, already these names would interfere. They can serve only to make you aware of that which you have to experience as unnamed. How does one cope with a personality who gives not one theology but two theologies, a positive one and a negative one, a rationalistic and a mystic theology? Someone who can just project his thoughts in the spirituality of the periods from which Christianity is born can cope with it quite well. If one describes, however, the course of human development during the first Christian centuries in such a way as modern materialists do, then the writings of the Areopagite appear more or less folly. Then one simply rejects them as a rule. If you can project your thoughts, however, in that which one experienced and felt at that time, then you understand what a person like the Areopagite only wanted to express, actually, at which countless human beings aimed. For them God was a being that one could not recognise at all if one took one way to Him only. For the Areopagite God was a being that one had to approach on rational way by naming and name finding. However, if you go this way only, you lose the path, and then you lose yourself in cosmic space void of God. Then you do not find your way to God. Nevertheless, one must take this way, for without taking this way you cannot reach God. However, one has still to take a second way. This is just that which aims at the unnamed. However, if you take one way only, you find God just as little; if you take both, they cross, and you find God at the crossing point. It is not enough to argue whether one way or the other way is right. Both together are right; but every single one leads to nothing. One has to take both ways and the human soul finds that at the crossing point at which it aimed. I can understand that some people of the present shrink from that what the Areopagite demands here. However, this lived with the persons who were the spiritual leaders during the first Christian centuries, then it lived on traditionally in the Christian-philosophical current of the West, and it lived up to Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas. It lived, for example, in that personality whose name I have called already yesterday, in Scotus Eriugena. As I have told yesterday, Vinzenz Knauer and Franz Brentano who were usually meek flew into a rage if Plotinus came up for discussion. Those who are more or less, even if astute and witty, rationalists will already rail if they come in contact with that which originated from the Areopagite, and whose last significant manifestation Eriugena was. A legend tells that Eriugena was a Benedictine prior in England in his last years. However, his own monks stabbed him repeatedly with their styluses—I do not say that it is literally true, but if it is not quite true, it is approximately true—until he was dead because he had still brought Plotinism into the ninth century. However, his ideas that further developed at the same time survived him. His writings had disappeared more or less; nevertheless, they were delivered to posterity. In the twelfth century, one considered Scotus Eriugena as a heretic. However, this did yet not have such a meaning as later and today. Nevertheless, the ideas of Scotus Erigena deeply influenced Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas. We realise this heritage of former times on the bottom of the souls, if we want to speak of the nature of Thomism. Something else is considered. In Plotinism, you can realise a very significant feature that arose from a sensory-extrasensory vision of the human being. One gets great respect for these things, actually, when one finds them spiritual-scientifically again. There one would like to confess the following. There one says, if one reads anything unpreparedly like Plotinus or that which is delivered from him, then it appears quite chaotic. However, if one discovers the corresponding truths again, these views take on a different complexion even if they were pronounced different at that time. Thus, you can find a view with Plotinus that I would like to characterise possibly in the following way. Plotinus looks at the human being with his bodily-mental-spiritual peculiarities from two viewpoints at first. He looks at them first from the viewpoint of the work of the soul on the body. If I wanted to speak in modern way, I would have to say the following. Plotinus says to himself at first, if one looks at a child growing up, then one realises that that still is developed which develops from spiritual-mental as a human body. For Plotinus is everything that appears material in particular in the human being—please be not irked by the expression—an exudate of the spiritual-mental, a crust of the spiritual-mental as it were. We can interpret everything bodily as a crust of the spiritual-mental. However, when the human being has grown up to a certain degree, the spiritual-mental forces stop working on the bodily. One could say, at first, we have to deal with such an activity of the spiritual-mental in the bodily that this bodily is organised from the spiritual-mental. The spiritual-mental works out the human organisation. If anything in the organic activity attains a certain level of maturity, we say, for example, for that activity to which the forces are used which appear later as the forces of memory, just these forces which have once worked on the body appear in a spiritual-mental metamorphosis. What has worked first materially from the spiritual-mental, gets free from it if it is ready with its work, and appears as an independent being, as a soul mirror if one wants to speak in the sense of Plotinus. It is exceptionally difficult to characterise these things with our concepts. One comes close to them if one imagines the following. The human being can remember from a certain level of maturity of his memory. He is not able to do this as a little child. Where are the forces with which he remembers? They develop the organism at first. After they have worked on the organism, they emancipate themselves and still work on the organism as something spiritual-mental. Then only the real core, the ego lives again in this soul mirror. In an exceptionally pictorial way this double work of the soul, this division of the soul into an active part which builds up, actually, the body and into a passive part is portrayed by that ancient worldview. It found its last expression in Plotinus and devolved then upon Augustine and his successors. We find this view in a rationalised form, in more physical concepts with Aristotle. However, Aristotle had this view from Plato and from that on which Plato rested. If you read Aristotle, it is in such a way, as if you have to say, Aristotle himself strives for conceptualising all old views abstractly. Thus, we recognise in the Aristotelian system that also continued the rationalistic form of that which Plotinus gave in another form, we recognise a rationalised mysticism in Aristotelianism continued until Albert and Thomas Aquinas, a rationalistic portrayal of the spiritual secret of the human being. Albert and Thomas knew that Aristotle had brought down that by abstractions what the others had in visions. Therefore, they do not at all face Aristotle in such a way as modern philosophers and philologists do who quarrel over two concepts that come from Aristotle. However, because the Aristotelian writings have not come completely to posterity, one finds these concepts or ideas without being related to each other. Aristotle considered the human being as a unity that encloses the vegetative, lower principle and the higher principle, the nous,—the scholastics call it intellectus agens. However, Aristotle distinguishes the nous poietikos and the nous pathetikos, an active and a passive human mind. What does he mean with them? You do not understand what he means if you do not go back to the origin of these concepts. Even like the other soul forces these two kinds of mind are active in the construction of the human soul: the mind, in so far as it is still active in the construction of the human being which does not stop, however, like the memory once and emancipates itself as memory but is active the whole life through. It is the nous poietikos. This builds up and individualises the body from the universe for itself in the sense of Aristotle. It is the same as the soul constructing the human body of Plotinus. That what emancipates itself then what is destined only to take up the outer world and to process the impressions of the outer world dialectically is the nous pathetikos, the intellectus possibilis. What faces us as astute dialectic, as exact logic in scholasticism goes back to these old traditions. You do not cope with that what happened in the souls of the scholastics if you do not take into consideration this impact of ancient traditions. Because all that had an impact on the scholastics, the big question arose to them that one normally regards as the real problem of scholasticism. In that time when humanity had still a vision that produced such things like Platonism or its rationalistic filtrate, Aristotelianism, in which, however, still the individual feeling had not reached the climax, the scholastic problems were not yet there. Since that which we call intellect and which has its origin in the scholastic terminology on one side is just an outflow of the individual human being. If we all think in the same way, it is only because we all are organised equally individually and that the mind is attached to the individual that is the same in all human beings. They think different, as far as they are differentiated. However, these nuances have nothing to do with real logic. However, the real logical and dialectic thinking is an outflow of the general human but individually differentiated organisation. Thus, the human being stands there as an individuality and says to himself, in me the thoughts emerge by which the outside world is represented internally; there the thoughts which should give a picture of the world are arranged from the inside. There, on one side, work mental pictures inside of the human being that are attached to single individual things, like to a single wolf or to a single human being, we say to Augustine. Then, however, the human being gets to other inner experiences, like to his dreams for which he does not find such an outer representative at first. There he gets to those experiences, which he forms for himself, which are chimaeras as already the centaur was a chimaera to scholasticism. Then, however, are on the other side those concepts and ideas that shimmer, actually, to both sides: the humanity, the type or genus of lion, the type or genus of wolf, and so on. The scholastics called these general concepts universals (universalia). When the human beings still rose to these universals in such a way as I have described it yesterday, they felt them as the lowest border of the spiritual world. To experience in such a way, it was not yet necessary to have that individual feeling which prevailed then during the later centuries. With individualised feeling, one said to himself, you rise from the sensory things up to that border where the more or less abstract, but experienced things are, the universals humanity, lion, wolf and so on. Scholasticism understood this very well that one could not say just like that, these are only summaries of the outer world, but this became a problem for it with which it struggled. We have to develop such general concepts, such universal concepts from our individuality. If we look out, however, at the world, we do not have the humanity, but single human beings, not the type wolf, but single wolves. However, on the other side, we cannot regard that what we study as the wolf type or the lamb type, the material that is contained in these summaries as the only real. We cannot accept this just like that, because then we would have to suppose that a wolf becomes a lamb if one feeds it with lambs only long enough. Matter does not do it; the wolf remains wolf. Nevertheless, the wolf type is something that one cannot only equate with the material just like that. Today it is often a problem, which people do not at all take seriously. Scholasticism struggled intensely with this problem, just in its period of bloom. This problem was directly connected with the ecclesiastical interests. We can get an idea of it if we take into consideration the following. Before Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas appeared with their special elaboration of philosophy, already some people had appeared like Roscelin (R. of Compiègne, ~1050-1120, French theologian and philosopher), for example, who asserted and were absolutely of the opinion that these general concepts, these universalia were nothing but that what we summarise from the outer individual things. They are, actually, mere words, mere names.—This nominalism regarded the general things, the universalia, only as words. However, Roscelin was dogmatically serious about nominalism, applied it to the Trinity, and said, if—what he considered right—this summary is only a word, the Trinity is only a word, and the individuals are the only real: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Then the human mind summarises this three: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit with a name only.—Medieval spirits expanded such things to the last consequences. The church was compelled to declare this view of Roscelin a partial polytheism and the doctrine heretic on the synod of Soissons (1092). So one was in a certain calamity compared with nominalism. A dogmatic interest united with a philosophical one. In contrast to today, one felt it as something very real in that time, and just with the relationship of the universalia to the individual things Thomas and Albertus struggled spiritually; it is the most important problem for them. Everything else is only a result as far as everything else got a certain nuance by the way how they positioned themselves to this problem. However, just in how Albertus and Thomas positioned themselves to this problem, all forces are involved which had remained as tradition of the Areopagite, of Plotinus, Augustine, Eriugena and many others. One still knew that there were human beings who beheld beyond the concepts into the spiritual world, into the intellectual world, in that world about which also Thomas speaks as about a reality in which he realises the intellectual beings free of matter that he calls angels. These are not mere abstractions but real beings that have no bodies only. Thomas placed these beings into the tenth sphere. While he imagines the earth circled by the sphere of the moon, then of Mercury, Venus, and sun and so on, he comes via the eighth and the ninth spheres to the Empyrean, to the tenth sphere. He imagines all that absolutely interspersed with intelligences, and the intelligences to which he refers back at first send down what they have as their lowest border as it were in such a way that the human soul can experience it. However, in such a way as I have pronounced it now, in this form which is more based on Plotinism it does not appear from the mere individual feeling to which just scholasticism had brought itself, but it remained belief for Albert and Thomas that there is the manifestation of these abstractions above these abstractions. For them, the question originated, which reality do these abstractions have? Albert and Thomas still had an idea of the work of the mental-spiritual on the bodily and its subsequent mirroring if it has worked enough on the bodily. They had images of all that. They had images also of that which the human being becomes in his single individual life what he takes up as impressions of the outside world and processes it with them. Thus, the idea developed that we have the world round ourselves, but this world is a manifestation of the spiritual. While we look at the world, while we see the single minerals, plants, and animals, we suspect that that is behind them, which manifests from higher spiritual worlds. If we consider the realms of nature with logical decomposition and with the greatest possible mental capacity, we get to that which the spiritual world has put into the realms of nature. Then, however, we have to understand the fact that we are in contact with the world by our senses. Then we turn away from the world. We keep that as memory, which we have taken up from the world. We look back remembering. There only the universal like “humanity” appears to us in its inner conceptual figure. So that Albert and Thomas say, if you look back if your soul reflects that to you, which it has experienced in the outside world, then the universalia live in your soul. Then you have universalia. You develop from all human beings whom you have met the concept of humanity. You could live generally only in earthly names if you remembered individual things only. While you do not at all live only in earthly names, you must experience universalia. There you have universalia post res, universals that live after the things in the soul. While the human being turns his soul to the things, he does not have the same in his soul what he has after if he remembers it, but he is related to the things. He experiences the spiritual in the things; he translates it to himself only into the form of the universalia post res. While Albert and Thomas suppose that the human being is related to something real when he is related to his surroundings by his intellectual capacity, so not only to that what the wolf is because the eye sees it, the ear hears it and so on, but because the human being can think about it, the type “wolf” develops. He experiences something that he grasps intellectually abstractly in the things that is also not completely absorbed in the sensory entities. He experiences the universalia in rebus, the universals in the things. One cannot distinguish this easily because one normally thinks that that which one has in his soul at last as a reflection is also the same in the things. No, it is not the same in the sense of Thomas Aquinas. What the human being experiences as an idea in his soul and explains with his mind to himself is that by which he experiences the real, the universal. So that the form of the universals after the things is different from that of the universals in the things, which then remain in the soul; but internally they are the same. There you have one of the scholastic concepts whose clearness one normally does not consider. The universals in the things and the universals after the things in the soul are as regards content the same, different only after their form. Then, however, something else is added. That which lives in the things individualised points to the intellectual world again. The contents are the same, which are in the things and after the things in the human soul, but they have different form. Again in other form, but with the same contents: are the universalia ante res, the universals before the things. These are the universals as they are included in the divine mind and in the mind of the divine servants, the angels. Thus, the immediate spiritual-sensory-extrasensory view of ancient time changes into the views which were illustrated only just with sensory pictures because one cannot even name that which one beholds in extrasensory way after the Areopagite if one wants to deal with it in its true figure. One can only point to it and say, it is not all that which the outer things are. - Thus, that which presented itself as reality in the spiritual world to the ancient people becomes something for scholasticism about which just that astuteness of thinking has to decide. One had brought down the problem that was once solved by beholding into the sphere of thinking, of the ratio. This is the nature of the view of Thomas and Albert, of High Scholasticism. It realises above all that in its time the feeling of the human individuality culminates. It realises all problems in their rational logical figure. The scholastic thinking struggles with this figure of the world problems. With this struggle and thinking, scholasticism stands in the middle of the ecclesiastical life. On the one side, is that of which one could believe in the thirteenth, in the twelfth centuries that one has to gain it with the thinking, with the astute logic; on the other side were the traditional ecclesiastical dogmas, the religious contents. Let us take an example how Thomas Aquinas bears a relation to both things. There he asks, can anyone prove the existence of God by logic? Yes, one can do it.—He gives a range of proofs. One of them is, for example, that he says, we can only gain knowledge at first, while we approach the universalia in rebus and look into the things. We cannot penetrate by beholding—this is a simply personal experience of this age—into the spiritual world. We can thereby only penetrate with human forces into the spiritual world that we become engrossed in the things, get out the universalia in rebus. Then one is able to conclude what is about these universalia ante res before, he says. We see the world moved; a thing always moves the other because it itself is moved. Thus, we come from one moved thing to another moved thing, from this to another moved thing. This cannot go on endlessly, but we must come to the prime mover. If he were moved, however, we would have to look for another prime mover. We must come to an unmoved prime mover.—With it, Thomas just reached—and Albert concluded in the same way—the Aristotelian unmoved mover, the first cause. The logic thinking is able to acknowledge God as an inevitably first being as the inevitably unmoved prime mover. No such line of thought leads to Trinity. However, it is traditional. One can reach with the human thinking only so far that one tries whether the Trinity is preposterous. There one finds: It is not preposterous, but one cannot prove It, one must believe It, one must accept It as contents up to which human intellectuality cannot rise. Thus, scholasticism faces the so important question at that time, how far can one reach with the human intellect? However, by the development of time it was placed still in quite special way in this problem, because other thinkers preceded. They had accepted something apparently quite absurd. They had said, something could be theologically true and philosophically wrong. One can say flatly, it can absolutely be that things were handed down dogmatically, as for example the Trinity; if one contemplates then about the same question, one comes to the contrary result. It is possible that the intellect leads to other results than the religious contents.—This the other problem that the scholastics faced: the doctrine of double truth. Both thinkers Albert and Thomas made a point harmonising the religious contents and the intellectual contents, searching no contradiction between that what the intellect can think, indeed, only up to a certain limit, and the religious contents. However, what the intellect can think must not be contradictory to the religious contents; the religious contents must not be contradictory to the intellect. This was radical in those days because the majority of the leading church authorities adhered to the doctrine of double truth: that—on one side—the human being must simply think something reasonable, as regards content in one figure, and the religious contents can give him it in another figure. He has to live with these two figures of truth.—I believe that one could get a feeling for historical development if one thought that people were with all their soul forces in such problems few centuries ago. Since these things still echo in our times. We still live in these problems. Tomorrow we want to discuss how we live in these problems. Today I wanted to characterise the nature of Thomism generally in such a way as it lived at that time. The main problem to Albert and Thomas was how do the intellectual contents of the human being relate to the religious contents? First, how can one understand what the church specifies as faith, secondly how can one defend it against that which is opposite to it? Albert and Thomas were very much concerned with it. Since in Europe that did not live exclusively which I have characterised, but there were still other views. With the propagation of Islam, other views still asserted themselves in Europe. Something of Manichaean views had remained in Europe. However, there was also the doctrine of Averroes (Ibn Rushed, 1126-1198, Andalusian polymath) who said there, what the human being thinks with his pure intellect does not belong to him especially; it belongs to the whole humanity.—Averroes says, we do not have the intellect for ourselves; we have a body for ourselves, but not everybody has an intellect for himself. The person A has an own body, but his intellect is the same as that of person B and again as that of person C.—One could say, to Averroes a uniform intelligence of humanity exists, in which all individuals submerge. They live with their heads in it as it were. When they die, the body withdraws from this universal intelligence. Immortality does not exist in the sense of an everlasting individual existence after death. What lasts there is only the universal intelligence, is only that which is common to all human beings. Thomas had to count on this universality of the intellect. However, he had to position himself on the viewpoint that the universal intellect not only combines intimately with the individual memory in the single human being, but that that which during life combines also with the bodily forces form a whole that all formative, vegetative and animal forces, as the forces of memory are attracted by the universal intellect. Thomas imagines that the human being attracts the universal and then draws that into the spiritual world, which his universal has attracted so that he brings it into the spiritual world. Hence, to Thomas and Albert not pre-existence but post-existence can be as Aristotle had assumed. In this respect, these thinkers continue Aristotelianism, too. Thus, the big logical questions of the universals combine with the questions that concern the world destiny of the single human beings. In the end, the general logic nature of Thomism had an impact on all that—even if I wanted to characterise the cosmology of Thomas and the enormous natural history of Albert. This logical nature consisted of the following: we can penetrate everything with keen logic and dialectic up to a certain border, and then we must penetrate into the religious contents. Thus, both thinkers faced these two things without being contradictory: what we grasp with our intellect and what is revealed by the religious contents can exist side by side. What was, actually, the nature of Thomism in history? For Thomas it is typical and important to prove God, while he strains the intellect and at the same time, he has to concede that one comes to an idea of God as one had it as Jahveh rightly in the Old Testament.—That is, he gets to that uniform God whom the Old Testament called the Jahveh God. If one wants to get to Christ, one has to pass over to the religious contents; one cannot get to it with that which the human soul experiences as its own spiritual. Something deeper was in the views of double truth against which High Scholasticism simply had to oppose out of the spirit of time, that one could not survey, however, in the age in which one was surrounded everywhere by the pursuit of rationalism, of logic. The following fact was behind it: those who spoke of double truth did not take the view that that which theology reveals and that which the intellect can reach are two different things, but are two truths provisionally, and that the human being gets to them because he took part in the Fall of Man to the core of his soul. This question lives as it were in the depths of the souls until Albert and Thomas: did we not take up the original sin also in our thinking? Does the intellect lead us to believe other truth contents than the real truth because the intellect has defected from spirituality?—If we take up Christ in our intellect, if we take up something in our intellect that transforms this intellect, then only it consorts with the truth, with the religious contents. The thinkers before Thomas wanted to take the doctrine of the original sin and the doctrine of the redemption seriously. They did not yet have the power of thought, the logicality for that, but they wanted to make this seriously. They presented the question to themselves: how does Christ redeem the truth of the intellect that is contradictory to the spiritually revealed truth in us? How do we become Christians to the core? Since the original sin lives in our intellect, hence, the intellect is contradictory to the pure religious truth. Then Albert and Thomas appeared and supposed that it is wrong that we indulge in sinfulness of the world if we delve purely logically into the universalia in rebus if we take up that which is real in the things. The usual intellect must not be sinful. The question of Christology is contained in this question of High Scholasticism. High Scholasticism could not solve the problem: how can the human thinking be Christianised? How does Christ lead the human thinking to the sphere where it can grow together with the spiritual religious contents? This question shook the souls of the scholastics. Hence, it is,—although the most perfect logical technique prevails in scholasticism—above all important that one does not take the results of scholasticism, but that one looks through the answer at the big questions which were put at that time. One had not yet advanced so far with Christology that one could pursue the redemption from the original sin up to the human thinking. Hence, Albert and Thomas had to deny the intellect the right to cross the steps over which it can enter into the spiritual world. High Scholasticism left behind the question: how does the human thinking evolve into a view of the spiritual world? Even the most important result of High Scholasticism is a question: how does one bring Christology into thinking? How is thinking Christianised?—Up to his death in 1274, Thomas Aquinas could bring himself to this question. One could answer it only suggestively in such a way that one said, the human being penetrates into the spiritual nature of the things to a certain degree. However, then the religious contents have to come. Both must not be contradictory to each other; they must be in concordance with each other. However, the usual intellect cannot understand the contents of the highest things on its own accord, as for example, Trinity, the incarnation of Christ in the person Jesus and so on. The intellect can understand only so far that it can say, the world may have originated in time, but it may also exist from eternity. However, the revelation says, it originated in time. If you ask the intellect once again, you find the reasons, why the origin in time is more reasonable. More than one believes, that lives still in modern science, in the whole public life, which was left of scholasticism, indeed, in a special figure. Tomorrow we want to speak about how alive scholasticism is still in us and which view the modern human being has to take of that which has survived as scholasticism. |

| 74. The Redemption of Thinking (1956): Lecture III

24 May 1920, Dornach Translated by Alan P. Shepherd, Mildred Robertson Nicoll Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| 74. The Redemption of Thinking (1956): Lecture III

24 May 1920, Dornach Translated by Alan P. Shepherd, Mildred Robertson Nicoll Rudolf Steiner |

|---|