| 163. Chance, Necessity and Providence: Consciousness in Sleeping and Waking States

27 Aug 1915, Dornach Translated by Marjorie Spock Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| Just as in the earth's case the only thing that makes sense is to say that it undergoes an alternation between day and night because of its position in space, so human life undergoes an alternation between interest for the inner and interest for the outer scene. |

| What really matters is to note the salient facts in the case under study. We only know something about these higher beings if we are familiar with the state of consciousness in which the various hierarchies live and if we can describe it. |

| I'd like to show you at hand of an example that there are indeed individuals who possess understanding for such nuances of consciousness. Today is the 27th of August, Hegel's birthday, and tomorrow, the 28th, is Goethe's; they follow on one another's heels. |

| 163. Chance, Necessity and Providence: Consciousness in Sleeping and Waking States

27 Aug 1915, Dornach Translated by Marjorie Spock Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

In the preceding lectures, I have been calling attention to the fact that there will still be a great deal to say about a certain problem or question, even though it has already been the subject of discussion here from a great variety of viewpoints. That is the question of the alternating states of waking and sleeping in human beings. I have repeatedly spoken in public lectures of how this problem of sleep has occupied a more materialistically oriented science also, and how it is being handled. On several occasions I have referred to some of the various attempts that have been made to solve it. There is the so-called exhaustion theory, which is only one of the many that have been advanced in recent decades. This theory holds that we secrete substances resulting from the wear and tear of work and of our other activities during waking life, and that the sleeping state somehow eliminates these exhaustion products, which are then formed anew in the following period of waking consciousness. Now we must always take the position that such a theory—I mean, what it describes—does not have to be wrong from the standpoint of spiritual science just because of its purely materialistic origin. The materialistic rightness of this particular theory need not now be gone into at any further length; other theories have been advanced in the same matter, as I have just mentioned. But from the standpoint of spiritual science no question will be raised as to whether such a process can take place, whether exhaustion products are really secreted during day-waking consciousness and destroyed again at night. This actual process will not be brought into question or further discussed. It must be a main concern of spiritual science to examine a problem, to study life's riddles, in a way that really relates the standpoint from which they are studied to the insights that can be gained in a particular age. That will provide the right basis for bringing the right light to bear on facts such as the secretion of exhaustion products. In most of life's problems—indeed, in all of them—the point is to know what questions to ask, to avoid pursuing a mistaken line of questioning. In the case of the alternation between sleeping and waking the development of a viewpoint from which to study these two human states is all-important. And the proper light can be brought to bear upon certain phenomena of human life only if matters introduced in a very early phase of our spiritual scientific efforts are kept in mind. In the very early days I called attention to the fact that if we want to get an overview of world evolution we have mainly to consider seven stages of consciousness, seven life-conditions and seven form- states. Certain life-questions can be answered simply by considering changes in form; other questions can be illuminated by studying life-metamorphoses. But certain phenomena in life, certain facts of life cannot be illuminated any other way than by rising to a consideration of the various states of consciousness involved. It is quite natural, in considering the problem of waking and sleeping, to concern ourselves with questions of the difference involved in the two states of consciousness. For we have certainly learned from a great variety of studies that we are here dealing with different states of consciousness, so that the question of consciousness is the all-important one here. We must realize that our most important concern in dealing with this question is to base it on the matter of consciousness. We will have to ask ourselves what the real difference is between the waking and the sleeping states. And this is what we find: When we are awake—we need only to register what each one of us is conscious of—we look at the world around us and perceive it. And we will be able to say that when we are in the day- waking state, we cannot observe our own inner life as we do our surroundings. I have often called your attention to the fact of what a crude illusion it would be if we were to conceive of the study of anatomy as leading to observation of the inner man. Only what is external in us, though it lies beneath our skin, can be studied by material anatomy; our inner aspect cannot be studied during ordinary waking consciousness. Even what a person comes to know of himself while he is awake is the world's outer aspect, or, more exactly, that aspect of him that belongs to the external world. But if we now observe the human being from the contrasting aspect of the sleeping state, its essential characteristic, as you can see from the various discussions that have previously taken place here, is that he is observing himself. While we are in that condition, the object of our attention is the human being; our consciousness is occupied with ourselves. If you examine some of the most commonplace phenomena from this standpoint, you will find them readily comprehensible. Now if what materialistic science states on the subject of sleeping and waking were all that could be said about it, it would seem to contradict an observation I once made here, namely, that an independently wealthy person who hasn't made any particular effort is more often seen to fall asleep at lectures than someone who has been exerting himself at work. This observation would have to be wrong if tiredness were the real cause of sleep. What we have to consider here is that the coupon clipper who listens to a lecture is not focusing his day- waking interest on it, is perhaps not particularly interested in it, may even find it impossible to take an interest in it because he doesn't understand it and is therefore justified in his apathy. He is much more interested in himself. So he withdraws his attention from the lecture to concentrate upon himself. One could, of course, ask: why particularly upon himself? That too can easily be explained. There are certain reasons why the lecture doesn't interest him, and they are usually that he is more interested in other aspects of life than in those under discussion in the lecture, or, at least, in their relevance. But the lecture keeps him from occupying himself with what would otherwise be interesting him. A person who has no interest in hearing a lecture might conceivably prefer to spend the time eating oysters instead of attending the lecture. Perhaps he is more interested in the experience of eating oysters than in that provided by the lecture. But the lecture disturbs him; there is no way for him to eat oysters if he attends it. He behaves as though he wanted to hear it, but it keeps him from eating oysters. Since he can't be eating them, he settles for the only thing available besides the lecture that is disturbing him. The hour ahead is taken up with something that he can only hear, something without interest for him. So he turns his attention to the only other available interest: his own inner being, and enjoys himself! For his falling asleep is self-enjoyment. You can gather from what we have studied that sleeping consciousness is still at the stage that prevailed in man during the ancient sun period. It is the same consciousness we share with plants. We know both these facts from previous lectures. Now our sleeping man at the lecture is not in the same state of consciousness in which we would find him if he were enjoying the external world. He is working his way back into sub-consciousness as it were. But that doesn't matter; he enjoys himself anyhow. And his enjoyment comes from his interest in himself. So we must find it understandable that sleep takes over, not as a result of inner weariness but because his interest moves away from the outer scene, the lecture or the concert or whatever, to what does interest him. This is always the fact of the matter if one studies the alternation between sleeping and waking with thoroughness, and in its inner aspect. When we are awake, we may look upon our condition as one in which we turn our attention outward, to the world around us. We withdraw our interest from our inner life. The opposite is true of the sleeping state. Attention is directed inward to the self and withdrawn from what lies outside it. Since we have left our bodies during sleep, we actually see them from outside. We can, as you see, trace the alternation between sleeping and waking to another cause, and say that we live in successive cycles, in one of which our interest is awake to the world outside us, and in the other to our inner world. This alternation between outer and inner is one that belongs every bit as much to our life as the fact that the sun shines on the earth and then goes down, leaving it in darkness, belongs to the earth's life. In the latter case the spatial constellation is the factor involved in the alternation between light and darkness, bringing about the cycle of daytime and nighttime. Now you can easily see how mistaken it would be to say that the day is the cause of the night, and the night of the day. That would be what I have described to you in preceding lectures as a worm's philosophy. It is simply nonsense to call the day the cause of the night and vice versa; both result from the regular alternation in the spatial relationship between sun and earth. It makes just as little sense to say that sleep is the cause of waking, and waking the cause of sleep. Just as in the earth's case the only thing that makes sense is to say that it undergoes an alternation between day and night because of its position in space, so human life undergoes an alternation between interest for the inner and interest for the outer scene. These conditions have to succeed each other; anything else is out of the question. Life decrees that human beings must focus their attention on their surroundings for awhile, and then turn it inward, just as the sun, descending in the west, has no choice about what its further course will be. But we enter a realm here where the following must always be kept in mind: The sun has to make a certain period of hours into daytime, and another period into night. But human beings are in a position to vary things and upset routines, like the coupon clipper who sleeps even though he isn't tired, voluntarily turning his attention inward, enjoying himself, really enjoying his body, or like a student cramming for examinations who, to some extent, overcomes his need for normal sleep. Many students sleep very little before examinations. But this brings up the big questions we will be concerning ourselves with, questions about necessity in outer nature, questions about the frequently discussed subject of chance, both in nature and in human life, questions about providence that apply to the entire universe. As soon as we touch on the sphere of human life we come upon an element that belongs in the field of necessity, something necessary to man if he is to live and have his being in the world. There is much that we will be discussing in regard to this. What I've been telling you has been said not only—and please note the “not only” as well as a “partly”—to call your attention to the fact that we must try to get a proper perspective on the alternation between sleeping and waking. This means asking what sort of consciousness we have when we are awake. The answer is that the outer world rather than the human being is its object, that we forget ourselves and turn our attention to the surrounding world. Conversely, consciousness in sleep is such that we forget the world outside us and observe ourselves. But we return first to the state of consciousness we had on the sun; the fact that we enjoy ourselves is of secondary importance. But that is not the only reason why I have referred to this perspective; it was also to call attention to the importance of noting the ways consciousness is related to the world and to the fact that we can come to know the essential nature of certain things only by inquiring into the kind of consciousness involved. It is, for example, quite impossible to know anything of importance about the structure of the hierarchical order of higher spiritual beings unless we concern ourselves with their consciousness. If you go through the various lecture cycles, you will see what trouble was taken to characterize the consciousness of angels, archangels, and so on. For it is essential in any study to give careful thought to what constitutes the right approach. A person might say that he is quite familiar with the hierarchical order: first comes the human being, then the higher rank of angels, then the still higher archangels, then the archai, and so on. He writes them down in ascending order and claims to understand: each hierarchy is one step above the one before it. But if that were all one knew about these beings, one would know as little about the hierarchical order as one knows about the levels of a house from the fact that each higher story is superimposed upon the one below it; one could make a drawing that would fit both cases. What really matters is to note the salient facts in the case under study. We only know something about these higher beings if we are familiar with the state of consciousness in which the various hierarchies live and if we can describe it. This must form the basis of a study of them. The same thing holds true in the study of human beings. We know very little indeed about our inner being if we can say nothing further on the subject of the sleeping state than that our ego and astral body are outside our physical and etheric bodies. Though that is true, it is a totally abstract pronouncement, since it conveys no more information about the difference between sleeping and waking than one possesses in the case of a full and an empty beer glass; in the one case there is beer in it, and in the other the beer is elsewhere. It is true enough that the ego and the astral body have left the physical and etheric bodies of a sleeping person, but we must be of a will to go on to ever further and more inclusive concrete insights. We try to do this, for example, when we describe the alternation of interest in the two states of consciousness. I once made you a light red drawing of man, and then a blue one in illustration of my statements to the effect that, for the clairvoyant, the human being is in the hollow part shown in the drawings. If a person falls asleep and possesses a higher consciousness (it can be just the beginning of it; but even then we can really perceive, for we begin by observing ourselves), he sees this hollow part. At such moments we see clearly how mistaken the belief is that we are made of compact matter, that what seems to day-waking consciousness to be substantial is actually empty space. Of course, we must keep in mind that human beings are really outside their bodies during sleep. So they see the empty space surrounded by this aura. They are not in their bodies; they are looking on from outside them, so they see the empty space within the aura. It is a shaped yet hollow space. Looked at from outside, other kinds of spaces are of course filled with something. Therefore a person naturally appears in the shape he has when looked at with day-waking consciousness, but he is seen surrounded by what might be described as an auric cloud, an aura. We don't see him entirely clearly at first, but rather in an auric cloud that we must first penetrate: we see an auric cloud, outlining a shadowy form. It is as though we see the person in a more or less brilliant aura; viewed from outside, the space occupied by his physical form is left empty. I will resort to a trivial comparison to convey an adequate impression of this phenomenon, perceived when we become conscious during sleep. We have all had the experience of going about in a city when it is foggy or misty and have seen how the lights there appeared as though in a rainbow aura, without sharp outlines. This impression of lights like empty spaces in the surrounding fog is an experience everyone has had, and it is very similar to what I have been describing. The area imaginatively perceived is seen as though in a fog or mist, and the physical human beings are the empty dark spaces there inside it. We may say, then, that we see human beings through an aura when we attain to clairvoyance in our sleep. We became materialists when we learned to look directly at our fellow human beings instead of seeing their auras. That was brought about as a result of luciferic developments that made it possible to begin to see ourselves with day-waking consciousness. And this helps us to understand an important passage in the Old Testament, the one that says that people went about naked prior to the seduction by Lucifer. This is not to be taken as meaning that their state of awareness in their nakedness at all resembled what yours would be if you were to do the same thing now; it means that they previously saw the surrounding aura. So they had no such awareness of the human being as we would have now if people were to run about in the nude, for they perceived human beings spiritually clothed; the aura was the clothing. And when that innocence was lost and human beings were condemned to a materialistic way of life, meaning that they could no longer perceive auras, they saw what they had not seen while the aura was still perceptible, and they began to replace auras with clothing. That is the origin of clothing; garments replaced auras. And it is actually a good thing in our materialistic age to know that people clothed themselves for no other reason than to emulate their aura with what they wore. That is especially the case with rituals, for everything that is worn on such occasions represents some part of the aura. You can see for yourselves, too, that Mary and Joseph and Mary Magdalene wear quite different garments. One wears a rose-colored dress with a blue mantle, the other a blue robe with a red mantle. Mary Magdalene is often portrayed in a yellow garment by those who were still familiar with the old tradition or who still retained remnants of clairvoyance. An attempt was always made to reproduce the aura of the individual in question, for people were aware that the aura ought to be indicated, ought to find expression in the clothing worn. An aberration typical of our materialistic age afflicts certain circles who see an ideal in doing away with clothing and who regard the so-called nudity cult as extremely wholesome; materialism can always be counted upon to draw the practical conclusions of its thinking. There is actually a magazine devoted to this cause that calls itself Beauty. A misunderstanding is at the root of this; the magazine believes itself to be serving something other than the crassest, coarsest materialism. But that is all that can be served when reality is seen exclusively in what external, sense-perceptible nature has brought forth. The wearing of clothes originated as a means of preserving in ordinary life the state of consciousness that sees human beings surrounded by an aura. We should therefore find out where the contemporary tendency to do away with clothing comes from. It comes from a total absence of any imagination in clothing ourselves. No idealism is involved, but rather a lack of any imagination where beauty is concerned. For clothes are intended to beautify the wearer, and to see beauty only in unclothed human beings would, for our time, reveal an instinct for materialism. I intend at a later date to contrast this with the situation existing in Greek civilization. That civilization provides us with the best means of studying this matter in the light of what has just been said. Now it becomes more and more important for people to learn how various conditions of consciousness provide insights for a study of life. Sleeping and waking are alternations in states of consciousness. But while sleeping and waking bring about sharply marked changes in our state of consciousness, smaller changes occur as well. Day-waking consciousness also has its nuances, some of which tend more toward sleep, others more toward the waking state. We are all aware that there are individuals given to spending a large part of their lives not actually asleep, but drowsing. We say of them that they are “asleep,” meaning that they go through life as though in a dream. You can tell them something, and in no time at all they have forgotten it. We can't call it real dreaming, but things flit by them as though in a dream and are instantly forgotten. This drowsiness is a nuance of consciousness bordering on sleep. But if somebody beats another up, that is a nuance that goes beyond the state of ordinary sleep and doesn't remain just a mental image. Life presents a variety of nuances of consciousness; we could set up a whole scale of them. But they all have their own rightness. A lot depends on our developing a feeling for these nuances. A person occasionally has such a sense if he is born healthy and grows up in a healthy state. It is important to have a certain sensitivity for how seriously to take this or that in life, how much or how little attention to pay to it, what matters to take a stand on and what to keep to oneself. All this has to do with the asserting of consciousness, and such nuances do indeed exist. And it is very important to know, as we go through life, that life can develop in us the delicate sensitivity that tells us how much consciousness to focus on any particular matter, how strongly to stress something. We really make important progress both in leading a healthy life and in the possibility of contributing to orderly conditions in our environment if we pay attention to how strongly we should focus our consciousness on this or that. The state of consciousness we are in when we are among people and talking with them in an ordinary way about various matters is different from the state of consciousness in which a sense of delicacy forbids our discussing certain other subjects. These are two distinctly differing nuances of consciousness. But the presence of a sense of the fitness of things is simply another state of consciousness, and it is endlessly important in life to have an awareness of such considerations. I'd like to show you at hand of an example that there are indeed individuals who possess understanding for such nuances of consciousness. Today is the 27th of August, Hegel's birthday, and tomorrow, the 28th, is Goethe's; they follow on one another's heels. Now Hegel wrote an Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences among other works, and a first edition of it was published.1: This book is noteworthy in a certain respect. There would be absolutely no point in opening it at random and reading this or that page; you could make exactly as much sense out of it as out of Chinese. A statement taken at random from a page of Hegel would convey nothing whatsoever. In a lecture in Berlin last winter I explained how little sense it made to divorce one of Hegel's sentences from its context. For sentences in Hegel's encyclopedia make sense only when one has skipped over everything that poses riddles for the human mind and arrived at the place where Hegel says, “Considered in and of itself, being is the concept,” and so on. If one begins there and exposes oneself to all the rest of it, then and only then does every sentence make sense at the place where it stands; each sentence owes its meaning to its place in the whole. Well, so Hegel had his encyclopedia published. In the preface to the first edition he explained why he arranged it as he did. When there had to be a second edition, Hegel wrote a preface to that. Now an author can sometimes have quite an experience of life between two editions of a book. For even if one has already become acquainted with one's fellow men, one feels oneself duty bound not to see them entirely in the light in which they sometimes reveal themselves; and besides, one can tell quite a bit about them from the reception the book is given. That was true in Hegel's case also. So then he wrote a preface to the second edition, and there are important passages in it. I am going to read you two such, one the very first sentence; the second, sentences from the second page. The preface to the second edition begins as follows: “The well-disposed reader will find that several sections have been revised and developed in sharper definition. I have taken pains therein to make my presentation a less formal one and to bring abstract concepts closer to the layman's understanding, making them more concrete by using more extensive exoteric annotations.” He was concerned, you see, to explain esoteric matters exoterically. The book continues:

This is proof that Hegel tried to shape the first edition in what was for him an esoteric manner, and that it was only in the second edition that he added what seemed to him exoteric aspects. Our time often possesses no understanding for these exoteric and esoteric elements; it doesn't so easily embark on the course Hegel travelled, who wanted to keep to himself everything originating in his own subjective view of a matter. And it was only after he had built up a complete organismic structure and freed it from any subjective aspects that he was willing to present this objective material in his book; he remained of the opinion that one's own path in achieving an insight was something that should be kept a private matter. In this, he evidenced sensitive feeling for the difference between two states of consciousness: that into which he wanted to enter when addressing the public, and that other developed for communing with himself. And then the world urged him, as the world so often does, in creating undesirable outcomes, to overcome this embarrassment of his for a certain period. For what lay at the bottom of his feeling was embarrassment, impelling him to silence about the way he had arrived at his concepts. As you know, embarrassment usually makes people blush. We would have to say, meaning something spiritual thereby, that Hegel blushed spiritually when he had to write a thing like his preface to the second edition. Here you see one of those nuances of consciousness over which embarrassment extends. I wanted to demonstrate with an example how nuances of consciousness show up in life, including nuances in actions of the will and in what we do. We need to become ever more fully aware that life really must consist of such nuances, that we have to relate differences in states of consciousness to everything we do. Sleeping and waking involve very marked differences. But there can also be a nuance of consciousness in which we are aware that a matter concerns not just ourselves but the surrounding world as well; another, in which we confront the world with awareness that we must tread gently; and still another in which we know that what we do must be done with ourselves alone, or only in the most intimate circle. The concepts and ideas we garner from spiritual science really make a difference in life. They teach us to recognize subtle subjective differences, provided we aren't disposed to know them only from the usual standpoint, realizing instead that a serious concern with spiritual science makes us a gift of this capacity for practical tact. But that serious concern with spiritual science must be present. It is of course absent if we project into spiritual science the sensations, desires, and instincts that ordinarily prevail. If that is the case, what is derived from spiritual science amounts to little more than can be garnered from any other indifferent source of learning. I've been speaking of nuances of consciousness and saying that there are nuances within the waking states very close to sleep. But it can happen that a person lacks the inclination to concern himself with certain details and subtleties, as in the case of the coupon clipper in yesterday's lecture. One may enjoy reading books or lecture cycles, but experience a dwindling consciousness at certain places in the text, and drowsiness sets in; the conscientiousness required to overcome such a condition is simply not there to call upon. That is why I have continued to stress that things should not be made too easy for people desiring to involve themselves with spiritual science. We hear again and again that books should be written in a popular style, that Theosophy is not popular enough.2: I discern behind such comments a wish for books that people could drowse through in a way they can't with Theosophy. It is vitally necessary to have sufficient interest for objective facts to rid ourselves of certain feelings and sensations we have had in the past; if we allow ourselves to drowse as we confront this or that theme in spiritual science that ought to engage our interest, we would stay awake only in the case of those matters most easily absorbed. And such a lack of objective interest leads to an inevitable development. The coupon cutter feels obligated to listen to the lecture, for lecture-going is part of a proper lifestyle, but he suffers tortures because of his total lack of interest. But he is gradually relieved; he enjoys himself, and sometimes even falls soundly asleep, a condition he doesn't have to guard against unless he starts snoring. All of this is a perfectly natural development. Now let us picture this process transferred to another kind of consciousness. Let us imagine a person who lacks the needed full interest in the concrete details of spiritual science. He feels that he is listening best when he is not paying attention to details. I have even heard the comment, “Oh, what he is saying isn't the important thing; it's the ‘vibrations,’ ‘the way it's said.’” The lecturer can often discern this type of drowsy listening in the listener's appearance. This is exactly the same situation on the soul level as that of the coupon clipper in external life. For if attention is being given to “vibrations” instead of to what spiritual science is offering, it turns the hearer's interest inward, as happens when the coupon clipper is enjoying himself. It may be that such a person describes himself between lectures as taking an interest in what the lecture offered, and claims interest in this or that theme. But he is really gossiping about his or someone else's previous incarnations. He has, in other words, shifted everything to an interest in himself in an identical internalizing process. We really see the same process here that goes on in the external life of the coupon clipper, who falls asleep at every lecture, in the case of those who feel that details are not important, but who claim an interest in spiritual science they really lack. So they fall asleep as to details, and their interest is transferred to their own personalities. Things of this sort have to be made clear. If we were to see them clearly, much that happens would not occur. I would like to see you make a study of the nuance levels of consciousness as I have tried to describe them. The last example given should perhaps not be taken amiss now or at any other time. There is no question that the movement of spiritual science is met with a good deal of sleepiness, while a strong tendency to self-enjoyment gets the upper hand, with the result that spiritual science is used only as a means of indulging in self-enjoyment. But we want to concentrate on nuances of consciousness, for unless we do so we will not be able to achieve an understanding of necessity, chance, and providence.

|

| 163. Chance, Necessity and Providence: Necessity and Chance in Historical Events

28 Aug 1915, Dornach Translated by Marjorie Spock Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| And he believes that they can be answered only if he understands “productive powers and germs,” understands, in other words, how outer experience contains a hidden clue to the way the thread of necessity runs through everything that happens. |

| When we look at the phenomena surrounding us, we seek the spiritual life, the truly living life of the spirit that underlies them, whereas Hegel, since he could go no further, sought the invisible idea, the fabric of ideas, first the fabric of ideas in pure logic, then that behind nature, and finally that underlying everything that happens as a spiritual element. |

| Where, then, must we look for the facts underlying history? That is the question now confronting us. In the case of individual lives we have to look for the thoughts underlying gesture. |

| 163. Chance, Necessity and Providence: Necessity and Chance in Historical Events

28 Aug 1915, Dornach Translated by Marjorie Spock Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

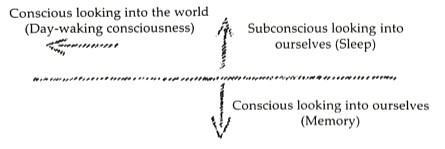

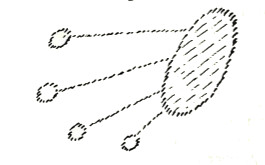

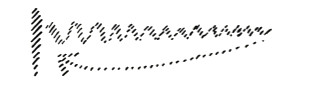

I want, as I've said, to use these days to lay the foundation we will need to bring the right light to bear on the concepts chance, necessity, and providence. But today that will require me to introduce certain preparatory concepts, abstract counterparts, as it were, of the beautiful concrete images we have been considering.1 And to do the job as thoroughly as we must, a lecture will have to be added on Monday. That will give us today, tomorrow (after the eurythmy performance), and Monday at seven. The performance tomorrow will be at three o'clock, and a further lecture will follow immediately. For contemporary consciousness as it has come into being and gradually evolved up to the present under the influence of materialistic thought the concepts necessity and chance are indistinguishable. What I am saying is that many a person whose consciousness and mentality have been affected by a materialistic outlook can no longer tell necessity and chance apart. Now there are a number of facts in relation to which even minds muddled by materialism can still accept the concept of necessity, in a somewhat narrow sense at least. Even individuals limited by materialism still agree that the sun will rise tomorrow out of a certain necessity. In their view, the probability that the sun will rise tomorrow is great enough to be tantamount to necessity. Facts of this kind occurring in the relatively great expanse of nature and natural happenings on our planet are allowed by such people to pass as valid cases of Necessity. Conversely, their concepts of necessity narrow when they are confronted with what may be called historical events. And an outstanding example is Fritz Mauthner, whose name has often been mentioned here; he is the author of Critique of Language, written for the purpose of out-Kanting Kant, as well as of a Philosophical Dictionary. An article on history appears in the latter. It is extremely interesting to see how he tries there to figure out what history is. He says, “When the sun rises, I am confronted with a fact.” To take an example, we have been able today, the 28th of August 1915, to witness the fact that the sun has risen. That is a fact. And now he concludes that we can ascribe this rising of the sun to a law, to necessity, only because it happened yesterday and the day before yesterday, and so on, as long as people have been observing the sun. It was not just a case of a single fact, but of a whole sequence of identical or similar facts in outer nature that brought about this recognition of necessity. But when it comes to history, says Mauthner, Caesar, for example, was here only once, so we can't speak of necessity in his case. It would be possible to speak of necessity in his existence only if such a fact were to be repeated. But historical facts are not repeated, so we can't talk of necessity in relation to them. In other words, all of history has to be looked upon as chance. And Mauthner, as I've said, is an honest man, a really honest man. Unlike other less honest individuals, he is a man who draws the conclusions of his assumptions. So he says of historical “necessity,” for example, “That Napoleon outdid himself and marched to Russia or that I smoked one cigar more than usual in the past hour are two facts that really happened, both necessary, both—as we rightly expect in the case of the most grandiose as well as the most absurdly insignificant historical facts—not without consequences.” To his honest feeling, something that may be termed historical fact, like Napoleon's campaign against Russia (though it could equally well be some other happening) and the reported fact that he smoked an extra cigar, are both necessary facts if we apply the term “necessity” to historical facts at all. You will be amazed at my citing this particular sentence from Mauthner's article on history. I cite it because we have here an honest man straightforwardly admitting something that his less honest fellows with a modern scientific background refuse to admit. He is admitting that the fact that Caesar lived cannot be distinguished from the fact of Mauthner himself having smoked an extra cigar by calling upon the means available to us and considered valid by contemporary science. No difference can be ascertained by the methods modern science recognizes! Now he takes a positive stand, declaring his refusal to recognize a valid difference, to be so foolish as to represent history as science, when, according to the hypotheses of present-day science, history cannot qualify as a science. He is really honest; he says with some justification, for example, that Wundt set up a systematic arrangement of the sciences.2 History was, of course, listed among them. But no more objective reason for Wundt's doing this can really be discovered than that it had become customary, or, in other words, it happens to be a fact that universities set up history faculties. If a regular faculty were provided to teach the art of riding, asserts Mauthner—and from his standpoint rightly—professors like Wundt would include the art of riding in their system of the sciences, not from any necessity recognized by current scientific insight, but for quite other reasons. We really have to say that the present has parted ways to a very considerable extent with what we encounter in Goethe's Faust: this can be quite shattering if we take it seriously enough.3 There is much, very much in Faust that points to the profoundest riddles in the human soul. We simply don't take things sufficiently seriously these days. What does Faust say right at the beginning, after he has spoken of how little philosophy, jurisprudence, medicine, and theology were able to give him as a student, after expressing himself about these four fields of learning? What science and life in general have given him as nourishment for his soul has brought him to the following conviction:

What is it Faust wants to know, then? “Germs and productive powers”! Here, the human heart too senses in its depths a questioning about chance and necessity in life. Necessity! Let us picture a person like Faust confronting the question of necessity in the history of the human race. Such an individual asks, Why am I present at this point in evolution? What brought me here? What necessity, running its course through what we call history, introduced me into historical evolution at just this moment? Faust asks these questions out of the very depths of his soul. And he believes that they can be answered only if he understands “productive powers and germs,” understands, in other words, how outer experience contains a hidden clue to the way the thread of necessity runs through everything that happens. Now let us imagine a personality like Faust's having, for some reason or other, to make an admission similar to Fritz Mauthner's. Mauthner is, of course, not sufficiently Faustian to sense the consequences Faust would experience if he had to admit one day that he could distinguish no difference between the fact that Caesar occupied his place in history and the fact of having smoked an extra cigar in the past hour. Just imagine transferring into the mind of Faust the reflection on the nature of historical evolution voiced by Mauthner from his particular standpoint. Faust would have had to say, I am as necessary in ongoing world evolution as smoking an extra cigar once was to Fritz Mauthner. Things are simply not given their due weight. If they were, we would realize how significant it is for human life that an individual who embraces the entire scientific conscience of the present admits the impossibility of distinguishing, with the means currently available to science, between the fact that Caesar lived and the fact that Mauthner smoked an extra cigar, in other words, admits that the necessity in the one case is indistinguishable from the necessity in the other. When the time comes that people sense this with a truly Faustian intensity, they will be mature enough to understand how essential it is to grasp the element of necessity in historical facts, in the way we have tried to do with the aid of spiritual science in the case of many a historical fact. For spiritual science has shown us how the facts relative to the successive historical epochs have been injected, as it were, into the sphere of external reality by advancing spiritual evolution. And what we might state about the necessity of this or that happening at some particular time differs very sharply indeed from the fact of Fritz Mauthner smoking his extra cigar. We have stressed the connection between the Old and the New Testaments, between the time preceding and the time following the Mystery of Golgotha, and stressed too how the various cultures succeeded one another in the post-Atlantean epoch and how the various facts occurring during these cultural periods sprang from spiritual causes. The angle from which we view things is tremendously important. We should be aware of the consequences of the assumptions presently held to have sole scientific validity. Days like yesterday, which was Hegel's birthday, and today, which is Goethe's, should be festive occasions for realizing how necessary it is to recall the great will-impulses of earlier times, to recall Hegel's and Goethe's impulses of will, in order to perceive how deeply humanity has become implicated in materialism. There have always been superficial people. The difference between our time and Goethe's and Hegel's is not that there were no superficial people then, but rather that in those days the superficial people could not manage to get their outlook recognized as the only valid one. There was that slight difference in the situation. Yesterday was Hegel's birthday; he was born in Stuttgart on August 27, 1770. Since it was impossible for him, living at that time, to penetrate into truly spiritual life as we do today with the aid of spiritual science, he sought in his way to lay hold on the spiritual element in ideas and concepts; he made these his spiritual foothold. When we look at the phenomena surrounding us, we seek the spiritual life, the truly living life of the spirit that underlies them, whereas Hegel, since he could go no further, sought the invisible idea, the fabric of ideas, first the fabric of ideas in pure logic, then that behind nature, and finally that underlying everything that happens as a spiritual element. And he approached history too in such a way that he really accomplished much of significance in his historical studies, even if in the abstract form of ideas rather than in the concrete form of the spiritual. Now what does a person who honestly adopts Fritz Mauthner's standpoint do if, let us say, he sets about describing the evolution of art from Egyptian and Grecian times up to the present? He examines the documented findings, registers them, and then considers himself the more genuinely scientific the less ideas play into the proceedings and the more he keeps—objectively, as he thinks—to the purely external, factual evidence. Hegel based his attempt to write the history of art on a different approach. And he said something, among other things, that we are of course able to express more spiritually today: If we conceive, behind the outer development of art, the flowing, evolving world of the ideal, then and then only will the idea that has, so to speak, been hiding itself, try to issue forth in the material element, to reveal itself mysteriously in the material medium. In other words, the idea will not at first have wholly mastered matter, but expresses itself symbolically in it, a sphinx to be deciphered, as Hegel sees it. Then, in its further development, the idea gains a further mastery over matter, and harmony then exists between the mastering idea and its external, material expression. That is its classic form. When, finally, the idea has worked its way through the material and mastered it completely, the time will come when the overflowing fullness of the world of ideas will run over out of matter, so to speak; the ideal will be paramount. At the merely symbolic level, the idea cannot as yet wholly take over the material. At the classic stage, it has reached the point of union with matter. When it has achieved romantic expression, it is as though the idea overflowed in its fullness. And now Hegel says that we should look in the surrounding world to see where these concepts are exemplified: the symbolic, sphinx-like form of art in Egypt, the classic form in Greece, the romantic form in modern times. Hegel thus bases his approach on the unity of the human spirit with the spirit of the world. The world spirit must allow us thoughts about the course of art's evolution. Then we must rediscover in the outer world what the world spirit first gave to us in thought form. This, says Hegel, is the way external history too is “constructed.” He looks first for the progressive evolution of ideas, and then confirms it at hand of external events. That is what the Philistines, the superficial people, have never been able to grasp, and it is their reason for reproaching Hegel so bitterly. A person who is superficial despite his belonging to a spiritual scientific movement wants above all to know about his own incarnation, and there were of course people in Hegel's time too who were superficial in their own way. You can see from one of Hegel's remarks that there was one such. As you've seen, Hegel followed the principle of first lifting himself into the world of ideas and then rediscovering in the world around him what he had come to know in the ideal world. Now the superficial critics had of course risen up in arms against this, and Hegel had to make the following comment: “In his many-sided naivete Herr Krug has challenged natural philosophy to perform the sleight of hand of deducing his pen only.” “Deducing” was the term used to denote a rediscovering in the outer world of everything that had first been discovered in the inner world. The person referred to in this remark was Wilhelm Traugott Krug, who was teaching at Leipzig at that time.4 Oddly enough, Krug was the predecessor of Mauthner in having written a philosophical dictionary, though he did not succeed in becoming a leading authority in his day. But he said, “If individuals like Hegel search for reality in ideas and then want to show, from the idea's necessity, how external reality coincides with it, then someone like Hegel had better come and demonstrate that he first encountered my pen as an idea.” Krug remarks that Hegel with his “idea” is not convincing in his assertions about the development of art from Egyptian to Greek to modern times, but if Hegel could “deduce” Krug's pen from his idea of it, that would impress him. Hegel comments in the passage mentioned above, “It would have been possible to give him the hope of seeing this deed accomplished and his pen glorified if science had progressed so far and so cleared up everything of importance in heaven and on earth in the past and present as to leave nothing of greater importance in doubt” than Herr Krug's pen. But in today's world the mentality characteristic of superficial people is really dominant. And Fritz Mauthner would have to say honestly that there is no possibility of distinguishing between the necessity of Greek art coming into being at a certain time and the necessity involving Herr Krug's pen or his own extra cigar. Now I have already called your attention to the prime importance of finding the proper angle from which to illuminate these lofty concepts of human life. We need to find the right angles from which to study necessity, chance, and providence. I suggested that you picture Faust in such relation to the world that he would have to despair of the possibility of discovering any element of necessity. But now let's imagine just the opposite and picture Faust conceiving of himself in relation to a world where nothing but necessity exists, a world where he would have to regard every least thing he did as conditioned by necessity. Then he would indeed have to say that if there were no chance happenings, if everything had to be ruled by necessity, “no dog would endure such a curst existence,” and this not because of what he had been learning but because of the way the world had been arranged. And what would a person amount to if there were truth in Spinoza's dictum that everything we do and experience is every bit as necessitated as the path of a billiard ball which, struck by another, has no choice but to move in a way determined by the particular laws involved?5 If that were true, nobody could endure such a world order, and it would be even less bearable for natures aware of “productive powers and germs!” Necessity and chance exist in the universe in such a way that they correspond to a certain human yearning. We feel that we couldn't get along without both of them. But they have to be properly understood, to be judged from the right angle. To do that in the case of the concept of chance naturally requires abandoning any prejudices or preconceptions we may have on the subject. We will have to examine the concept very closely so that we can replace the cliche that this or that “chanced” to happen—as we are often forced to say—with something more suitable. We will have to search out the fitting angle. And we will find it only if we go a bit further in the study we began yesterday. You are familiar with the alternating states of sleeping and waking. But we recognize that waking consciousness too has its nuances, and that it is possible to distinguish between varying degrees of awakeness. But we can go further in a study of that state. It is basically true that from the moment we awaken until we fall asleep again, our waking consciousness takes in nothing but objects in the world around us, senses their action, and produces our own images, concepts, and ideas. Sleeping consciousness, which has remained at the level of plant consciousness, then lets us behold ourselves as described yesterday, and, since our consciousness in this state is plantlike, this is a pleasurable absorption in ourselves. Now if we penetrate fully into the nature of human soul life, we come upon something that fits neither day nor night consciousness. I am referring to distinct memories of past experiences. Consider the fact that sleeping consciousness doesn't involve remembering anything. If you were to sleep continuously, you wouldn't need to remember previous experiences; there would be no such necessity, in any case. We do remember to some extent when we are dreaming, but in the plant consciousness of sleep we remember nothing of the past. It is certainly clear that memory plays no special part in sleep. In the case of ordinary day-waking consciousness we must say that we experience what is around us, but experiencing what we have gone through in the past represents a heightening of waking consciousness. In addition to experience of our present surroundings we experience the past, but now in its reflection in ourselves. So if I draw a horizontal line (see drawing) to represent the level of human consciousness, we may say that we look into ourselves in sleep.  I will write “Looking into ourselves” here; we can call it a subconscious looking. Day-waking consciousness can be set down as “Looking out consciously into the world.” Then a third kind of inner experiencing that doesn't coincide with looking into the world is the conscious “Looking into ourselves in memory.” So we have “Conscious looking into ourselves” = memory“Consciousness looking into the world around us” = day-waking consciousness “Subconsciousness looking into ourselves” = sleep The fact is, then, that we have not just two sharply different states of consciousness, but three of them. Remembering is actually a deepened and more concentrated form of waking consciousness. The important thing about remembering is more than just being aware of something; we recapitulate awareness of it. Remembering makes sense only if we are aware of something all over again. Think a moment: if I encounter one of you whom I have seen before, but merely see him without recognizing him, memory isn't really involved. Memory, then, is recognition. And spiritual science teaches us too that whereas our ordinary day-waking consciousness, our consciousness of the world outside us, has reached the very peak of perfection, our remembering is actually only just beginning its evolution; it must go on and on developing. Metaphorically speaking, memory is still a very sleepy attribute of human consciousness. When it has undergone further evolution, another element of experience will be added to our present capacity, namely, the inner experiencing of past incarnations. That experiencing rests upon a heightening of our ability to remember, for no matter what else is involved, we are dealing here with recognition, and it must first travel the path of interiorization. Memory is a soul force just beginning its development./ Now let us ask, “What is the nature of this soul-force, this capacity to remember? What really happens in the remembering process?” Another question must be answered first, and that is, “How do we arrive, at this point in time, at correct concepts?” You get an idea of what a correct concept is if you are not satisfied with a meager picturing of it; in most cases people have their own opinion of things rather than genuine concepts. Most individuals think they know what a circle is. If someone asks, Well, what is it? they answer, Something like this, and draw a circle. That may be a representation of a circle, but that is not what matters. A person who only knows that this drawing approximates a circle and remains satisfied with that has no concept of what a circle is. Only someone who knows enough to say that a circle is a curved line every point of which is equidistant from the center has a correct concept of a circle. An endless number of points is of course involved, but the circle is inwardly present in conceptual form. That is what Hegel was pointing out: that we must get down to the concept underlying external facts, and then recognize what we are dealing with in outer reality on the basis of our familiarity with the concept. Let us explore what the difference is between the “half-asleep” status of the mere mental images with which most people are satisfied and the active possession of a concept. A concept is always in a process of inner growth, of inner activity. To have nothing more than the mental image of a table is not to have a concept of it. We have the concept “table” if we can say that it is a supported surface upon which other objects can be supported. Concepts are a form of inner liveliness and activity that can be translated into outer reality. Nowadays one is tempted to resort to some lively movement to explain matters of this sort to one's contemporaries. One really has an impulse to jump about for the sake of demonstrating how a true concept differs from the sleepy holding onto a mental image. One is strongly prompted to go chasing after concepts as a means of bringing people slightly into motion and enlivening the dreadfully lazy modern holding of mental images that now prevails; one wants to devote one's energies to clarifying the distinction between entertaining ordinary mental images and working one's way into the real heart of a matter. And why is one thus prompted? Because we know from spiritual science that the moment something reaches the level of the concept, the etheric body has to carry out this movement; it is involved in this movement. So we really must not shy away from rousing the etheric body if we intend to construct concepts. What, then, is memory? What is remembering? If I have learned that a circle is a curved line every point of which is equidistant from the center, and am now to recall this concept, I must again carry out this movement in my etheric body. From the aspect of the etheric body, something becomes a memory when carrying out the movement in question has become habitual there. Memory is habit in the etheric body; we remember a thing when our etheric body has become used to carrying out the corresponding movement. We remember nothing except what the etheric body has taken on in the form of habits. Our etheric bodies must take it upon themselves, under the stimulus of re-approaching an object, being repeatedly brought into motion by us and thus given the opportunity of remembering, to repeat the motion they carried out in first approaching that object. And the more often the experience is repeated, the firmer and more ingrained does the habit become, so that memory gradually strengthens. Now if we are really thinking instead of merely forming mental images, our etheric bodies take on all sorts of habits. But these etheric bodies are what the physical body is based on. You will notice that a person who wants to clarify a concept often tries to make illustrative gestures, even as he is talking about it. Of course we all have our own individual gestures anyway. Differences between people are seen in their characteristic gestures, that is, if we conceive the term “gesture” broadly enough. A person with a feeling for gesture learns a good deal about others from observing their gestures and seeing, for example, how they set their feet down as they walk. And the way we think when remembering something is thus really a habit of the etheric body. This etheric body is a lifelong trainer of the physical body—or perhaps I had better say that it tries to train the latter, but not entirely successfully. We can say, then, that the physical body, for example, the hand, is here:  When we think, we constantly try to send into the etheric body what then becomes habit there. But the physical body presents a barrier. Our etheric bodies can't manage to get everything into the physical body, and they therefore save up the forces thus prevented from entering the physical body. They are saved up and carried through the entire period of life between death and rebirth. The way we think and the way we imprint our memories upon the etheric body then comes to the fore in our next incarnation as our instinctive play of gesture. And when we see a person exhibiting habitual gestures from childhood on, we can attribute them to the fact that in his previous incarnation his thinking imprinted certain quite distinct mannerisms on his etheric body. If, in other words, I study a person's inborn gestures, they can become clues to the way he managed his thinking in past incarnations. But just think what this means! It means that thoughts so impress themselves upon us that they resurface as the next incarnation's gestures. We get an insight here into the way the thinking element evolves into external manifestation: what began as the inwardness of thought becomes the outwardness of gesture. Modern science, in its ignorance of what distinguishes necessity from chance, looks upon history as happenstance. In a list of words dating back to 1482, which Mauthner refers to, we read the words, “geschicht oder geschehcn ding, historia res gesta.” “Res gesta” is what history used to be called. All that is left of this today is the abstract remnant “regeste.” When notes are taken on some happening, they are called the “register.” Why is this? The word is based on the same root as “gesture.” The genius of speech responsible for the creation of these words was still aware that we have to see something brought over from the past in historical events. If what we observe in individual gesture is to be understood as the residue of past lives on earth, born with the individual into an incarnation, surely it is not complete nonsense to assume something like gestures in what we encounter in the facts of history. A series of facts surfaces in the way we walk, and these are the gestures of our thinking in past incarnations. Where, then, must we look for the facts underlying history? That is the question now confronting us. In the case of individual lives we have to look for the thoughts underlying gesture. If we regard historical events as gestures, where must we look for the thoughts behind them? We will take up the study of this matter tomorrow.

|

| 163. Chance, Necessity and Providence: Necessity as Past Subjectivity

29 Aug 1915, Dornach Translated by Marjorie Spock Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| It may be that the falsity was inherent, or else became attached to the concept as language underwent changes over a period of time and did not need to wait for a scientifically and critically advanced generation to discover it. |

| You see that if we are really intent upon understanding life, we have to deal seriously and conscientiously with matters like these. We have to try very conscientiously indeed to develop our thinking, noting errors of thought where they occur, for they are intimately bound up with errors in the way our lives are lived. |

| Only if people bestir themselves to grasp that the events that took place in the ancient moon, sun, and Saturn periods are now reflected in us, and are merely reflections of those ancient events, will they come to understand necessity. And now think back to our discovery that our conceptual world is of moon origin. |

| 163. Chance, Necessity and Providence: Necessity as Past Subjectivity

29 Aug 1915, Dornach Translated by Marjorie Spock Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

If you look at works such as that of Fritz Mauthner, to whom I have repeatedly referred, you will see what consequences necessarily result from taking the prevailing modern outlook seriously. Mauthner arrives at all sorts of very strange conclusions. One example is the way he links the concept “supply” with that of a “supply of words,” for he is a philologist. He divides the word “supply” into two categories of “illusory” and “useful” concepts. The real purpose of his philosophical dictionary is to demonstrate that most philosophical concepts belong in the useless category. Those who give a thorough reading to his comments on a concept or word in his Dictionary of Philosophy always end up with the admittedly subjective feeling of whirling around like a Chinaman trying to grab his own pigtail. You have the feeling as you finish one of his articles that you have been trying all the way through it to get hold of your pigtail, which a Chinaman wears hanging down behind him. But at the end there it is, still behind you; no amount of twirling results in catching up with it. There are, I must say, some very, very upsetting things for healthy minds to endure as they read an article such as the one on “Christianity.” But that is true of almost all the articles Mauthner has written. Now he takes great pains to eliminate all illusory concepts, admitting some of them into his dictionary for the sole purpose of denouncing them. I'll read a few very characteristic sentences from his introduction by way of illustration:

Now wouldn't you agree that this is quite nice? Humanity took many millennia, not just centuries, to replace phlogiston with another concept, and Lavoisier's replacement of phlogiston with evidence of the true nature of combustion was considered a most significant deed.1 But Mauthner finds it possible to comment that “the concept was false from the start because exact scrutiny could have discovered all along that it contradicted the facts of experience.” It really sounds as though if Fritz Mauthner had been born early enough, he would have seen to it that people didn't have to suffer for so long a time from the false concept phlogiston. He goes on to say, “The concept which only became a false one when the concept devil fell by the wayside, and the godless female could therefore no longer enter into fleshly commerce with the illusory concept devil. The concept devil too lived a sufficiently lengthy span and died out only when human learning became convinced that neither the devil nor any of his works were observable in the sphere of reality.”