| 287. The Building at Dornach: Lecture V

12 Oct 1914, Dornach Translated by Dorothy S. Osmond Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| 287. The Building at Dornach: Lecture V

12 Oct 1914, Dornach Translated by Dorothy S. Osmond Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

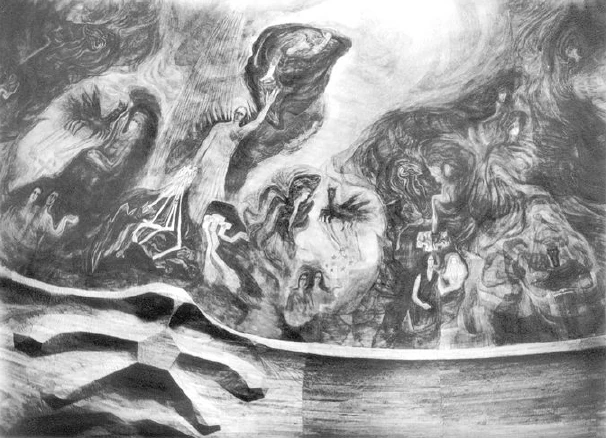

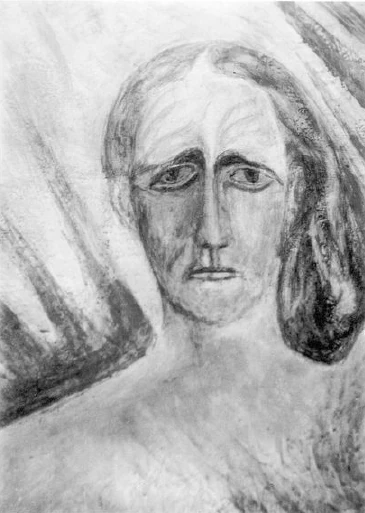

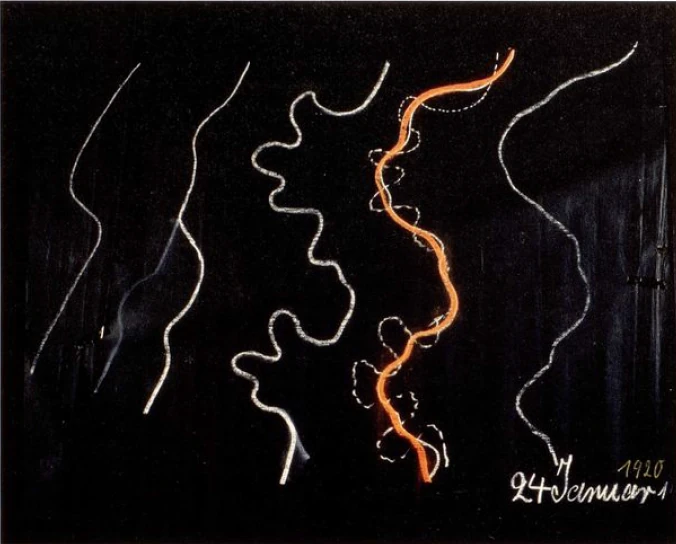

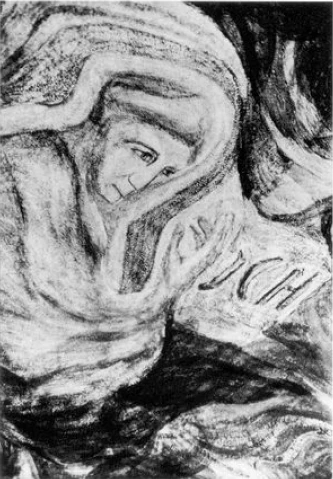

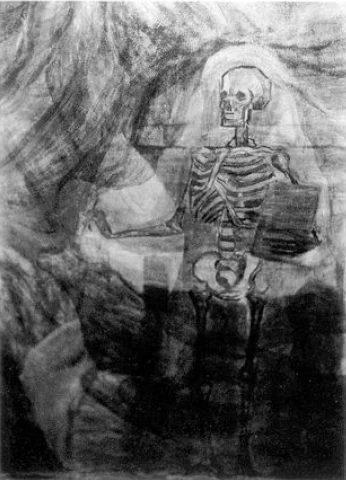

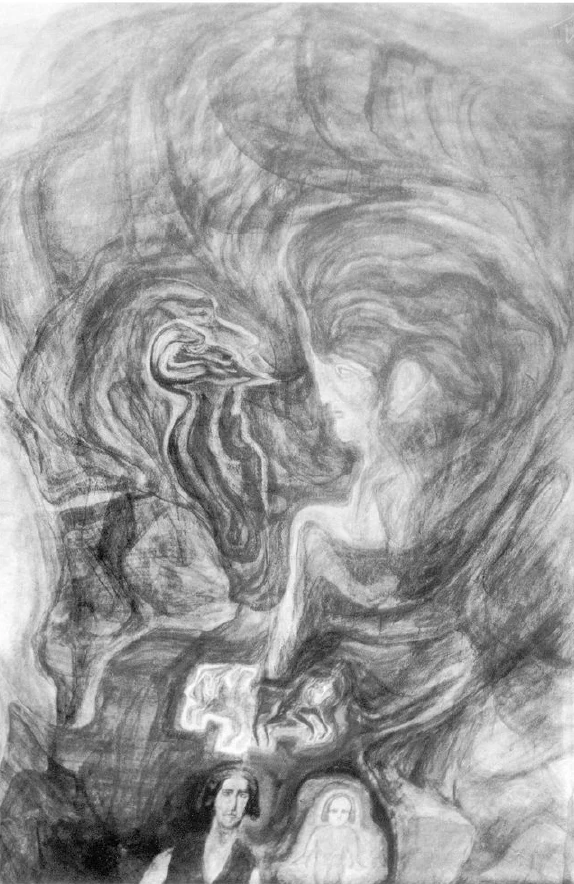

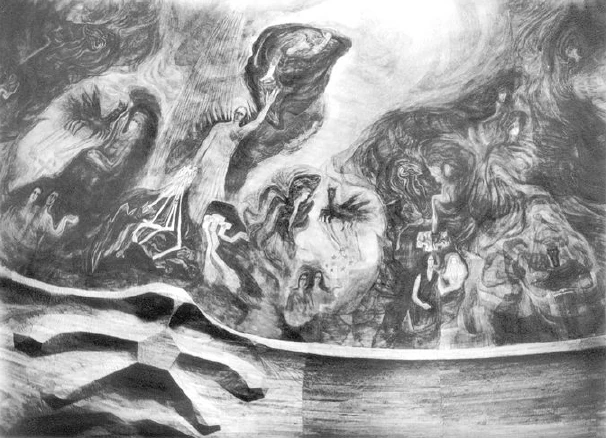

We spoke yesterday of the way in which the impulses of Will, Feeling and Thinking in man are brought to expression in our Building. It will be apparent to you from many things that have been said here recently that the art in our Building must contain a new element that has not hitherto existed in the evolution of art but is essential for the further progress of humanity. Admittedly it will be difficult from a purely external point of view to understand the real aim of this Building. A person may say to himself: I really can make nothing of it—and according to the standard of what he has hitherto regarded as artistic he will naturally have criticism to make. But remember, any new impulse in human evolution has always been criticised when it is judged according to the standards of the past. It will help us to understand the point here if we try to find a formula to express what is entailed by this renewal of the principle of art through the anthroposophical conception of the world. When we review the development of art, we can think of the architectural forms produced by mankind, either in the original Egyptian, Greek or Gothic architecture, or what represents the renewal in a later age of what was there in an earlier one—I mean the Renaissance. We can also think of sculpture, painting, and so forth. If we compare the effect made upon us by the essential character of these arts with what is aimed at in our Building, we can say; Everything that has been brought into being hitherto is like something in repose which, for us, has been wakened to life. Picture a human being in some fixed position. Somebody comes along and speaks to him - and he begins to walk, to move! This might well apply to the evolution of art up to our own day. We can regard it as something in repose, to which we would fain speak the magic word which rouses it into inner life and activity, into movement. This is what we want to achieve, because it is demanded by the impulses of transition which are at work in our time and call upon us to find a new impulse for the future evolution of humanity. To take an example, let us think of a beautiful Greek building. Its essential character consists in the symmetrical structures which mutually bear and support each other, just as the limbs of a human being standing immobile bear and support each other—but everything is at rest. Compare this with what we have aimed at in our Building. In time, of course, everything will develop, for we have been able to make only very primitive beginnings with the means and help available to us, In the Building we have movement from West to East; we have motifs which grow, as it were, from the simple forms to be seen in the West in the capitals and architraves into greater complication, and then become more inward and simpler again towards the small cupola. What was formerly a merely inorganic principle of symmetry has been brought into movement. What formerly was at rest is now in movement. This will have to come to expression in the painting—as far as it is possible in our age to achieve what must be the goal. In painting there are two poles. The one pole is that of drawing, the other that of colour, Fundamentally speaking, there are these two poles in all painting. Now a person may be a wonderful draftsman—that is to say, he may have the gift of reproducing in the lines he draws the inner form-quality of his subject, so that a picture of this form-quality is evoked by the drawing. Now we must be clear that anyone who concentrates on the actual drawing in a painted picture must inevitably be very one-sided in his relation to the Real—or, as is often said, to Nature. Nature does not work with lines only, but has far richer means for giving expression to what is inherent in a living being. Hence the painter or the draftsman, when he is inwardly moved by his subject, must express more in his lines than Nature is able to bring to expression in lines. But we shall never be able to avoid feeling that drawing in itself is nothing more than a substitute for what Nature can achieve. Whatever we may be capable of expressing through drawing, we can never produce anything that surpasses Nature; we cannot even equal Nature. Whatever we aim at in this respect must always remain a bungling attempt, for the simple reason that with the far richer means at her disposal, Nature is able to bring to expression the inmost essence of her creations. On this account, drawing can never be anything more than an auxiliary. And I believe that one who is a true draftsman will always feel that in drawing he is only producing something like a scaffolding to be removed later on, and that the less any evidence of it remains, the better. I think that anyone with artistic sensibility, looking at a painting in which the actual drawing is especially conspicuous, would have an impression similar to that made by a building from which the scaffolding has not been removed but still stands in position. Indeed the point can be reached where the actual drawing is felt to be just a clumsy adjunct to the work of art itself. It is rather different as regards the other pole of painting, the colour pole. Here we must bear in mind that colour is a fixation of something that, fundamentally speaking, is not present in Nature at all, or at most can be captured only momentarily. One cannot really count what is attached to some object, and which one then paints, as belonging to the element of colour in itself; for if a painter is concerned with making a meticulous reproduction of say, the colours of the clothes of people he is painting, he is certainly a bad artist. But fundamentally speaking, anyone who might try, in the colour of the face, for example, to bring the inner, vital processes of the human organism into evidence, would not be a good artist either. One who paints a pale face—assuming, to take the extreme case, that the pallor is intended to indicate that the person in question is ill—would certainly not have produced anything really artistic, not to speak of how inartistic it would be to depict a wine-bibber by painting him with a red nose! If it is desired to capture in colour something that is, so to say, stationary, and expresses itself in the world of reality, one is still not working with truly artistic impulses. But if one paints, let us say, a cloud, and in the cloud brings the whole magic of Nature to expression—perhaps the early morning sun and its effect upon the tints of the cloud—then one captures something that is transient in Nature and does not originate from the configuration of the actual cloud itself. What is captured here is something that is transient, but for all that rooted in the conditions prevailing in the whole environment, in the whole Cosmos, in so far as the Cosmos is involved in the phenomenon. In painting a cloud that at a particular hour of the day is brilliantly coloured, we really paint the whole universe as it is at that time. If in painting a human being we attempt to reproduce his inner, organic state, then, as I have said, we are not working with the true artistic impulses. But if we succeed in giving expression to what this human being has experienced—if, for example, we can suggest in the painting something that is the cause of the particular reddening of the countenance - then we are truly in the realm of the artistic; and still more is this the case when we can perceive from the picture itself what the experience has been, when the red of the cheeks tells us what the person must have undergone—again something that is not confined to the individual, but is in the whole environment, in the whole Cosmos. What I am saying here is connected in a certain way with something I spoke about in the lectures on “Occult Reading and Occult Hearing”. I said there that even in the waking life of day the soul is in reality always outside the body, and that the body is only a mirror by means of which man makes himself conscious of what is out there in the Cosmos. He alone is a true artist who lives, as it were, with the Cosmos and who regards what he has to portray simply as the stimulus to depict his life in the Cosmos. If we paint a cloud and therewith the whole Cosmos, we are outside the cloud in our life of feeling and ideation, and the cloud is there merely to enable us to project what lives in the whole Cosmos into a single entity. But if we want to live in this way in the Cosmos when it is a matter of using colour, we must awaken colour to life. Colours confront us as qualities of the beings in outer Nature. When our observation is confined to the physical plane we recognise the colours that are attached to the objects of Nature. If we are to see colours, a foundation is always necessary, with the possible exception of atmospheric phenomena such as a rainbow or other phenomena of the kind. Hence the rainbow has not without reason been regarded as something that unites the heavens, the spiritual, with the earth, because in the rainbow we see the heavens in colours; we actually see colours as such. I have already said that it is possible to plunge into the flowing world of colours, to live with the colours themselves, liberating them, as it were, from the objects. If we succeed in doing this, colour becomes the revealer of deep mysteries; a whole world resides in the flowing, surging sea of colour. But the world of colour must first be liberated from the conditions imposed upon it on the physical plane; the creative power of colour must be sought and found. If painting is to be an organic part of our Building, it must be born out of this impulse; the attempt must be made to portray in colour something that is not to be found on the physical plane, where everything coloured—with the exception of the rainbow and similar phenomena—is attached to objects. It must be possible to live in the colour blue, for instance, with one's whole soul, as if the rest of the world simply were not there; the soul must feel itself flowing out into the blue which fills the whole world. But if we really penetrate into the surging world of colour, the result will be that we shall not simply brush on tints, for we then discover the creative power of colour; we shall also find inner differentiation in colour. We shall find that blue has something about it that draws and attracts the soul, something in which our soul would like to lose itself, longing and yearning for it without end. We shall also find that forms arise out of the colour blue itself, forms which bring the secrets and the very soul of the universe to expression. From the creative power of colour a world will come into being, a world that has form, inner differentiation. Form will be born out of the colour itself. We shall feel that we are not only living in the colour, but that the colour itself gives birth to the form—in other words, the form is created by the colour. In this way we shall find our way, through colour, into the creative forces of the world. Only so can we succeed in painting in such a way that what we paint is not merely a covering of surfaces, but leads out into the whole Cosmos, participating in the life of the whole Cosmos. Reference was made yesterday to what the paintings in the two cupolas must represent; the impulses of Lemurian, Atlantean and our own life, as well as the impulses at work in the cultures of ancient India, ancient Persia, Egypt and Chaldea, Greece and Rome. In this way, the subjects will be inwardly understood and this inner understanding of colour, which, as it passes over into the actual painting, simultaneously becomes an understanding of form, will reveal to us what is actively at work in the evolution of humanity. A review of painting in the past will show that the tendency of this art has been to work with colour attached to objects on the physical plane. But colour must be freed from objects if the paintings in our cupolas are to achieve their aim. What is essential, therefore, is that the impulse of painting shall be deepened and quickened inwardly. It will he difficult to make our contemporaries understand what is being aimed at here. We shall have to resign ourselves to this for as long as people persist in judging a work of art as “right” or “good”, or I don't know what else, when it reminds them of some real object, so long will our paintings not be understood. As long as it is possible to say that a tree is well painted because it is naturalistic, giving the impression that one is standing in front of an actual tree—as long as this is the criterion for judging painting and art in general, just so long will people be unable to understand what our painting is intended to be. They will inevitably regard it as nonsense, and be incapable of seeing anything in it.—Why have works of art existed? Surely in order to be looked at! Who has ever supposed anything else? But what we want to create in our Building will certainly not be there merely to be looked at! Indeed, we may be happy if those people who believe, as a result of their previous experience and study, that works of art exist merely for the sake of being looked at, consider our art extremely bad. For one thing is certain: what these people do not want, is the very thing we want to achieve! Typical incidents often occur in this connection. One of our friends met me one day on the way from the glass-engraving studio to our house, and told me that he had been talking to an old gentleman who said that if the one who had conceived the idea of the domes of our Building had ever seen the Church of St. Peter in Rome, he would have designed them differently. Now the one who conceived the idea of our domes has seen St. Peter's not only once but many times, has admired and appreciated its greatness, but for all that he designed the domes as they are. It is quite natural that such things should happen. Even St. Peter's in Rome is there to be looked at—but what we are doing in our Building must not only be looked at, it must also be experienced. And what would have been the right answer to give to that old gentleman? The right answer would have been to say to him: Do you know the fairy-tale of the king's son who looked at things only through his window? And do you know what happened when one day he had to “eat of the serpent”? Then he began to understand what the sparrows on the roof-tops and the chickens in the courtyard say to one another.—That old gentleman had obviously not eaten of the serpent! What does it mean, to “eat of the serpent”? It means, not merely to have theoretical ideas about Spiritual Science, but to have been gripped by it in the very fibres of one's heart and soul, so that one feels oneself to be an actual image of this Spiritual Science. If we can feel this with our whole being then we have eaten of the serpent, and we shall know as an actual experience what is intended by our Building. We shall not merely look at it but experience what it aims to achieve; we shall realise that man, dimly and unconsciously in his life of will, passes from incarnation to incarnation, born in one incarnation in this people, in another incarnation in that. Just as this will-impulse in man can be experienced in the progression of the Building from West to East? in the successive motifs of the columns, capitals, and architraves, so can the element of feeling be experienced in what unfolds in the direction from below upwards—but it must be an actual experience. And the element of thought, when thinking is not merely abstract, cold, prosaic, but is quickened to life by the heart of the Cosmos itself—this should be experienced in the closure denoted by the domes, and also in their details. If, for example, the juxtaposition of one colour to another is one that is never found in Nature, if a being with facial features resembling those of man is portrayed in a colour which it could never have in Nature, one must feel in actual experience that what comes to expression there does so through its own inherent impulse. This will be achieved for the first time—even if only in the most elementary beginnings—if the attempts made are in any degree successful. In the paintings, particularly, things will not be as they are in Nature, but far rather as they are in the spiritual world. Two things must be achieved about which very few people nowadays are capable of thinking at all. But the fact that there are still a great many people who do not know, and moreover do not want to know, anything about the great vistas which lie ahead in evolution, certainly does not contribute to the welfare of humanity. To feel as it were in concentrated form those things of which our Building stands as the sign and token, we must quicken our inner life, quicken the soul to life through rich and varied experiences gathered from the manifold sources available in the world. Let us think of times very different from the present and of the mental horizon of men in those times. Think of the mental horizon of the Greeks and of all that was unknown to them but is well known to men of the present age. The Greeks did not know of America or Australia; they knew nothing of the Western hemisphere; they knew nothing of a very great many things we now know about Europe, Asia and Africa. Geographically, their horizon was narrow.—See what your feelings are when you study the map which a Greek was able to draw; think at tile same time of the rich inner world of the Greek, of his creative power. Compare what might be called the “geographical” chart of the heavens which the Greek was able to draw with present maps of the heavens. In ancient Greece, the map of the physical configuration of the earth was very meagre, the chart of the heavens very comprehensive. What was present in Greece was still, in essentials, a spiritual experience of the physical plane, geographically—within narrow limits; spiritually—a vista of wide expanses of the heavens. True, it was no longer as it had been, for example, in Egypt, when men looked out into the Cosmos and in astrological pictures still experienced something of the spiritual Being; whose physical expressions are the stars. Nevertheless, a precipitation of all this was still present in ancient Greece. When we read in Homer's “Iliad” that information is given by Thetis that Zeus can do nothing at the time because he is in Ethiopia and will not return home for twelve days—that still has an astrological meaning—but it is expressed in such a way that the reader does not notice that the description refers to the passage of the heavenly bodies through the Zodiac, When 'the Greek said “Zeus is with the Ethiopians”, he meant: Zeus is in a particular sign of the Zodiac—and the number twelve is also mentioned. All this Indicates a change from an earlier time, but on the other hand there is still an echo of what was revealed to men originally from the wide expanse of his spiritual horizon. Now let us turn away from Greece and consider the modern age. Geographically , the globe has nearly all been explored and only a few regions today are blank patches in the maps. We see the new age arising. America is included by the Oriental peoples in their earth—the America that simply did not exist for the Greeks. The geographical horizon widens and widens but the spiritual horizon, the map of the heavens, shrivels up completely. What does modern man know of the denizens presented to us in Greek mythology? He knows nothing at all! Europeans really live under the delusion that they still know something about the heritage left by ancient Greece.—What precedes the times of ancient Greece has no more than a spectral character for historians, however much they may investigate it by means of physical records.—But man is at least still a living reality in Greece. When the man of today imbibes what is imparted in the schools, he is assimilating history, and his soul lives in the history he has come to know in such an external way. We drag around with us a great deal of history—a very great deal of history. It is not so in the case of the Asiatic, nor is it yet so in the case of the American. Although he has his history, it is not a vital part of his life. The American is much less conscious of history than the European. There will be few Americans who attach any great importance to being able to trace back their genealogical tree through centuries, Probably there are very few indeed—but in Europe there are numbers. That is what I mean by “dragging around” with us the history upon which so much depends today in the whole configuration of life, of the social life too. A time is conceivable in a far distant future—for the occultist more than conceivable—when everything that we carry around with us as history since the Greek age will lie at rest (we will not speak of where it will be resting)—a time is conceivable when the tide of the peoples will have rolled across Asia over the Europe and America, and when men will know as little on the physical plane of all that we now recount and experience as European history as we today know of what happened in Europe four to six thousand years ago. We can look towards a time when this tide of the peoples will have rolled across Asia, a time when a quite different kind of life will develop and when everything that now stirs the very fibres of our hearts will lie as it were in a geological stratum of history. It will then lie as much in the past as what happened in Europe some four thousand years ago lies in the remote past for us. The time will come when Goethe, let us say, will be “discovered” in the same way as modern man has discovered the ancient world and its happenings from the earliest Egyptian hieroglyphs. For in the outer world there will be physical men who will need to discover Goethe in this way! We are gazing here at vast perspectives in the evolution of humanity. The Greeks knew nothing of America! In time to come no Greeks will be in existence, and the descendants of the present-day Americans will know of them only as a people belonging to a far, far distant past—or maybe they will know nothing of them at all! The process of which I have just spoken more as a physical process, also takes place in the spiritual, in the following sense.—In the course of his evolution into the future, man must acquire the faculties which enable him to discover the spiritual again, to know a future spiritual world which for most people today is as unknown as the present continent of America was unknown to the Greeks. We are at the beginning of this voyage of discovery to the spiritual America. In this connection—from the angle of scientific thinking—we stand, spiritually, at the same point where men were standing physically when the first ship sailed from the Old World to America. Spiritually, we are on the voyage of discovery to the other, spiritual half of our human existence. By saying this I only wanted to give some indication of the importance of Spiritual Science in the evolution of humanity. For now everyone can fill in for himself the gaps that still remain to complete the picture: Suppose for a moment that America had not been discovered, that Europeans were still living in ignorance of the existence of America. Is such a thing conceivable? It is quite inconceivable. But a time will come when it will be just as inconceivable that men were once incapable of discovering the spiritual world through Spiritual Science. This will be utterly inconceivable. And the thought can be carried even further. What effect has the expansion of the geographical horizon had upon humanity? if we look for the most spiritual culture that has developed on the earth up till now, we must look for it before America was discovered. For with the discovery of America, materialism begins. In a mysterious way, every geographical expansion is bound up with the expansion of materialism. Humanity must again acquire a spiritual knowledge of the world. This will be achieved through discovery of the spiritual America—when the path symbolised in our Building is found by the world outside. We have spoken of the element of progression in the Building from column to column, from architrave to architrave. That is the progression on the physical plane. But we can also follow the motifs from below upwards, we can look upwards.  What comes to light in the course of history—in so far as we can observe it externally—is expressed for us in the progression. But an inner deepening will become more and more necessary, a deepening of the soul which is at the same time—as in the case of Goethe's Faust who descends to the Mothers—an actual ascent into the spiritual world—naturally into the spiritual world of the good Spirits. But when man raises himself into the spiritual world, a kind of conclusion will eventually be reached. I say “conclusion”. Let us grasp what this word really implies. The idea of evolution prevailing today is that it is like a barrel that begins to roll and goes on rolling and rolling forever—it is also imagined that there was never any beginning to this process, that it has always been going on. People who talk about evolution today almost invariably imagine that there has always been evolution, that everything has always been evolving, that it has always been so! But in reality this is not the case. It is nothing but a bad habit of the mind, a slovenly kind of thinking, to conceive of evolution as having no limits either in the past or in the future. The geographical, physical evolution of the earth also means evolution for every race, every people, Yes, but that certainly has an ending, a conclusion, at some time or other! When everything has been discovered, there is an ending. We shall not be able to say then: Now we will equip our ship once again and make further discoveries. it is not true that evolution can continue endlessly; evolution has a conclusion. And just as physical evolution must have an end, so too will spiritual evolution have to have an end; an actual dome will arch one day over what humanity has experienced in the course of history. And true as it is that when the whole globe has been explored, no further ships will be equipped in order to discover still more distant lands on the earth, it is equally true that what is to be spiritually discovered by man will also one day actually have been discovered. The idea that men will go on investigating endlessly is the most erroneous there could possibly be. It is essential that thinking shall be in accordance with reality if sound ideas are to be developed. But so few people think in accordance with reality in our present age, although they are convinced that they do. One can, for example, come across people who say: When there is nothing more left to investigate, the world will be a very dull place. These people forget that according to the modern idea of evolution, investigation will never come to an end. Yet one day it will, just as geographical exploration of the earth will eventually come to an end. Those people who are tormented by the thought that investigation will one day come to an end and that there will be nothing more to do in this respect and who ask: “What will man do then?”—must be given the answer: That will be plain enough when the time comes, and in any case it will be something quite different from investigation. I have now given you a number of ideas, the purpose of which may puzzle you. But if you take them together you will be able to recognise this purpose yourselves. We see that the course of all historical life is reflected in the form of our Building. Men live on through the ages, just as in the Building one goes forward from column to column. They rise to a higher level just as one raises one's eyes to the columns, capitals and architraves. And they hope for a consummation—a conclusion—just as one will find it on looking up into the interior of the cupola. But there is to be a conclusion in history too—it is to be portrayed in the painting of the domes. This painting must not merely be a covering of the surface, but call forth the thought: When you come to the surface of the dome you will discover something.—One must forget that any physical structure is there. The physical element of the paintings must be pierced through; one must see through the surfaces into the expanse of the spiritual worlds. It may possibly be that we shall not succeed in this in the case of our Building, but as the principle is developed, one day, perhaps—as the result of Spiritual Science—men in some future time will behold a mighty dome whose configuration leads their gaze out into the infinitudes of spiritual life. If we live at some particular place on the earth and want to travel to another—at certain times we may want to do this but are prevented—then it is brought home to us that men can confront each other as enemies, that they can fight with one another about things of the earth, and even more than fight. But they cannot fight about the sun and the stars! Even though the Chinese have called their ruler the Son of the Sun, the Son of Heaven, and although for various reasons they have started wars on the earth, they have never started a war about ownership of the sun; it has never occurred to them to engage in strife with other nations about ownership of the sun. All kinds of things can be the cause of strife in the souls of the peoples spread over the earth; but that which directs men's gaze upwards into the spiritual worlds can never be an inducement to strife. It cannot lead to strife. It must be realised that a great deal has yet to happen in the course of earth-evolution before humanity will have advanced far enough to have such a vision of the spiritual world that Spiritual Science will be as the sun and the stars are in physical life. Much will be necessary before this point is reached—above all the point where, through Spiritual Science, men will begin to think not only with the instrument that is almost entirely used for thinking today, namely, the head. In a certain sense it is true to say that nothing is more remote from us than our heads! For in all, essentials, the head, as far as its main foundation is concerned, was already completed at the time of the ancient Sun-evolution. The rest is an inheritance, partly from the Saturn-evolution, and has developed to further stages; during the Moon-evolution another important impulse was given. But. what is thought out in the head is in reality as remote from men as is their knowledge of the Saturn-, Sun- and Moon- evolutions, Although there are often profound truths in many sayings current in everyday life, there is one very common phrase which should not be believed. One often hears it said “I have a mind (German, “head”) of my own.” That is an error. No one has a mind (or “head”) of his own; his head belongs to the Cosmos! If someone were to say: “I have a heart of my own”, he would be talking sense. But he talks nonsense when he speaks of having a head or a “mind” of his own. Men will have to begin to develop thoughts which are experiences in the way I described yesterday in speaking of the inner experience of rising from the recumbent into the standing position. We experience this too, merely with the head. In reality a stupendous process takes place in us when we raise ourselves out of the recumbent position in which we lie parallel with the surface of the earth, and place ourselves into the direction of the earth's radius—but we experience it in an utterly abstract way. This change of direction from the cross-beam of the cross to the vertical beam—when this becomes a real experience it is a stupendous. process, a cosmic process it is the Cosmic Cross.  This happens every day. But we do not by any means think every day about the fact that through the act of standing up end lying down, this Cross is inscribed into very life. It is a far cry for man from this abstract process of standing up and lying down, from this assumption of the form of the Cross, to the conception that can be expressed by saying: If man were not so constituted on the earth that he lies down and again stands up, the Mystery of Golgotha would not have been necessary. If someone utters the sound B—as for example in the word Building—and adopts the sign B for this sound, then the sign signifies the sound B. If someone asks for a sign to express the fact that the Mystery of Golgotha was necessary for earth-evolution, then it is to be found in the Cross, which embodies the acts of lying down and standing up. Because man is so constituted on the earth that he lies down and stands up, the Mystery of Golgotha had to take place. This will be known when men begin to think with the second brain—not with the “head-brain” but with a second brain to which I referred in the lectures on “Occult Reading and Hearing” when I said: The lobes of the brain must be regarded as arms held in a fixed position. If your arms and hands grew to your sides, you would think in such a way that there would be no possibility of doubting that this Cross is the appropriate sign for the Mystery of Golgotha. It is only the head-brain that is baffled by this kind of thinking. But it is also the head-brain that creates the soil for the many misunderstandings prevailing in the world. The reason why so many misunderstandings arise is because the head-brain alone is active and creative today. But the second brain must also become creative, creative to such a degree that something indicated figuratively a little while ago, is fulfilled. I said that the Greeks did not know of America. But when we go back to other ancient traditions, we find that there were times when the existence of America was indeed known. But then this knowledge was lost. There were also times when that which Spiritual Science is striving again to acquire was present. Spiritual Science knows that a great deal that formerly came to men from subconscious, dreamlike experiences, must come again consciously. Men also had something like a common speech, which only later differentiated. There is profound truth in the biblical legend of the Tower of Babel. But as long as men can only think with their heads they will not be able to be creative in the way they were creative in ancient times, for example, in speech. Spiritual Science, however, has within it the capacity to bring the elements of speech into movement. And when it is said that in our Building the element of art has been brought into movement, it must also be said that life itself must be stirred into movement. A vista can arise before us of a time when Spiritual Science will be truly creative, when through the thoughts and ideas unfolded in Spiritual Science, speech itself will become creative. Spiritual Science will one day be spread over the whole earth and will give rise to a common speech, corresponding to no speech or language existing at the present time. I am not referring to anything like Esperanto, for that is an artificial, inorganic invention. The speech of the future will come into being when man learns to live in sound itself, just as he can learn to live in colour. When he learns to live in sound, then the sound itself gives birth to the configuration, so that it becomes possible once again to create speech or language out of actual spiritual experience. We stand only at the very beginning of many things in Spiritual Science but as yet not even at the beginning of what has here been indicated. We must, however, keep it in our minds in order to realise the importance of Spiritual Science and to be aware that Spiritual Science bears within it a new knowledge, a new art, and even a new speech—a speech that will not be compiled artificially, but will be born. Just as men will never fight about the sun or the stars, they will also never fight about that new speech, by the side of which the other languages still in existence when this new speech has come into being can quite easily continue. As you will certainly have felt, we have placed a far-reaching ideal before our souls, a very far-reaching ideal. Most materialistic thinkers of the present time would certainly say: This is all airy nonsense, for the fool who can talk like this about the creative power of speech and about Spiritual Science must assuredly have lost all solid ground from under his feet. It is easy to imagine that if some person of eminence in our time had been listening from a corner to what has been said, he would have burst into derisive laughter at this flight into the clouds without solid ground underfoot. We, however, could have a certain understanding of his attitude, because by placing such lofty ideals before us, we have indeed lost the dense, solid earth underneath us. As long as the earth continues its evolution as a physical planet, this ideal will not be realised. The physical earth will have come to an end before this ideal is fulfilled. But the souls of men will live over into other planetary incarnations, and these souls will experience the fulfilment of this ideal if they become conscious of it in our time. Yes! Ahriman might stand there and be the arbiter between ourselves and the person we have imagined sitting in the corner, listening and chuckling to himself because he supposes us to have lost all ground from under our feet. Ahriman might well rub his hands and say: “They call that ‘ideals of the future’! They have lost the ground from under their feet; the gentleman up there on the hill says so himself. He mocks himself and knows not how! He is speaking the truth and is not aware that he is doing so”— But we know that even though we do not stand on the solid soil of the earth, we nevertheless stand in Reality with what we make into the living word of the soul, And why? Because we avow the Mystery of Golgotha in earnest and not with the shallowness that is so general today. We know that Christ lives, and that we can know the truth when we let Him be the great Teacher and Leader in our striving for spiritual wisdom. But He uttered words to this effect: You cannot truly believe in Me in your inmost being until you cease to acknowledge only those words and ideals which will perish together with the earth—(for the whole outer configuration of the earth will perish, the earth in its present form will pass away)—until you hearken to My true words. Of these true words He has said: “Heaven and Earth will pass away, but My words will not pass away”. Therefore in the life of soul we can have firm foundations, even though our ideals cause opponents to say that we no longer stand an the solid ground of the earth. If we are to make true avowal of the mystery of Golgotha we must have ideals which are more enduring than the earth and the configuration of the heavenly bodies circling around the earth in the Cosmos. We must hearken to the revelation of the Mystery of Golgotha which will be there even when the earth no longer exists, nor the heavens which now look down upon the earth. The meaning of the word that proceed from the Mystery of Golgotha is infinitely deep. And those who will not lift their souls from the ground into the cupola—which should be transparent in order that they may look into the spiritual world—those persons are not living in Reality. For if this dome, this cupola, is to be the expression in architecture of the Mystery of Golgotha, it must itself remind us of the words: “Heaven and Earth will pass away, but My words will not pass away.” |

| 288. Architecture, Sculpture and Painting of the First Goetheanum: The Symbolism of the Building at Dornach I

04 Apr 1920, Dornach Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| 288. Architecture, Sculpture and Painting of the First Goetheanum: The Symbolism of the Building at Dornach I

04 Apr 1920, Dornach Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

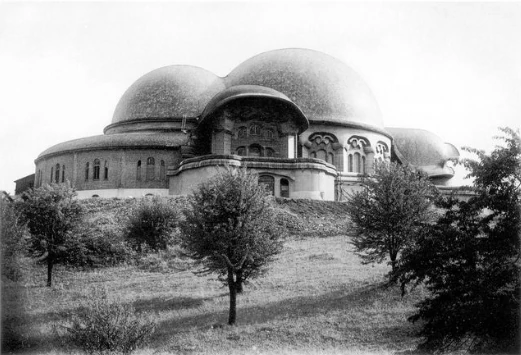

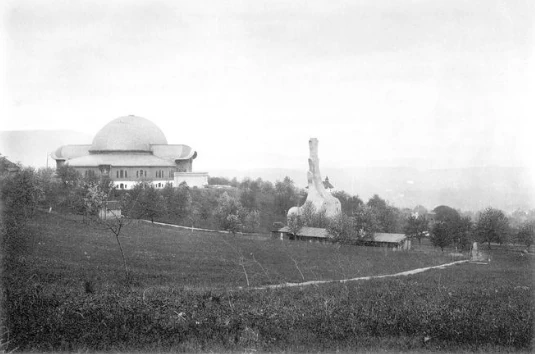

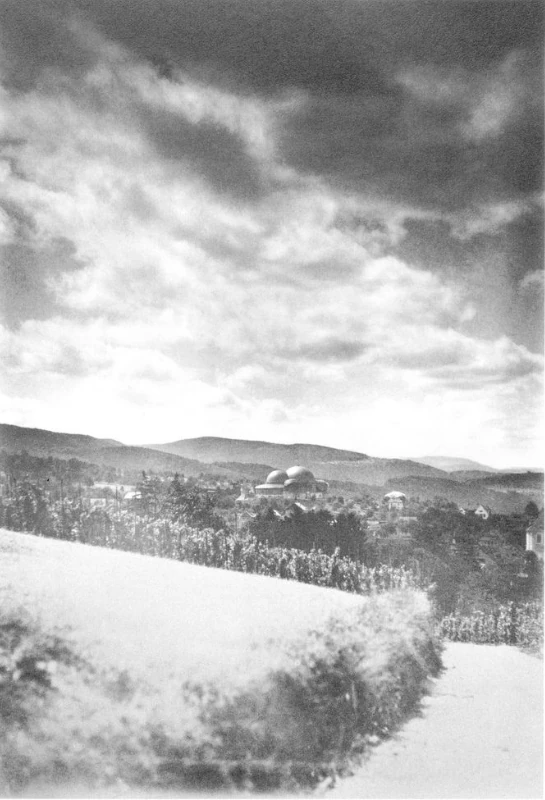

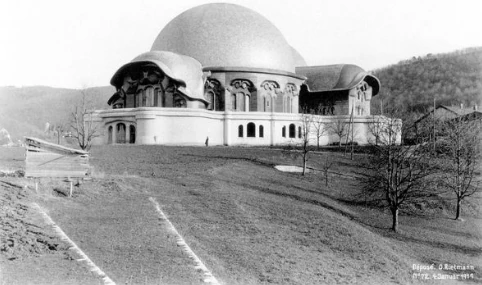

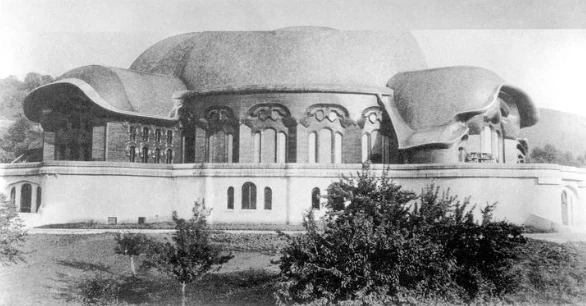

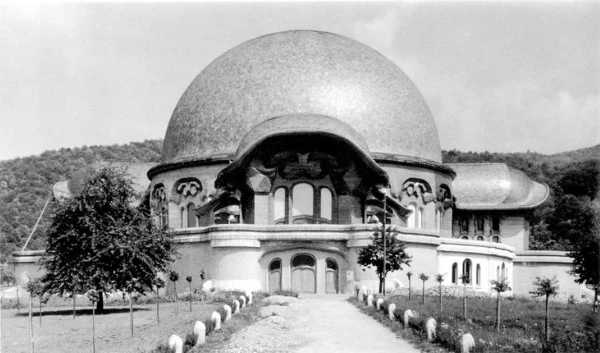

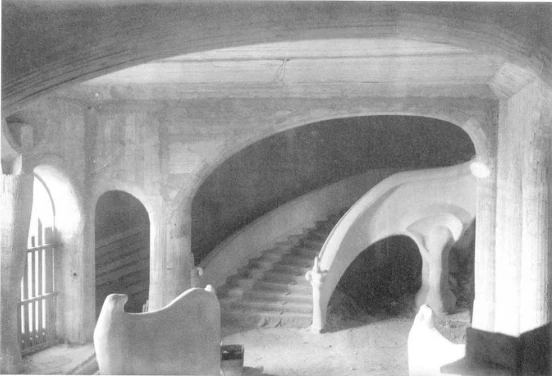

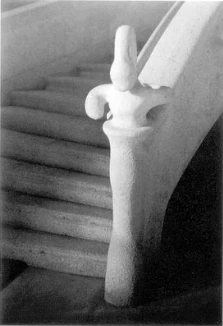

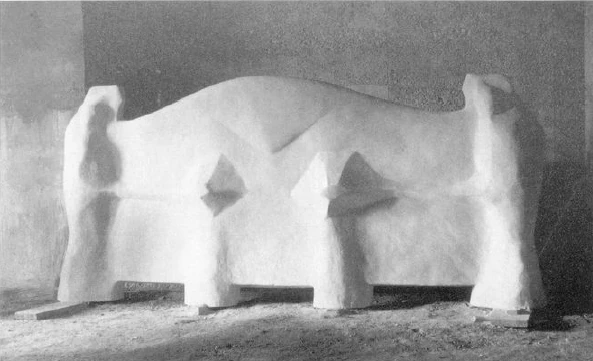

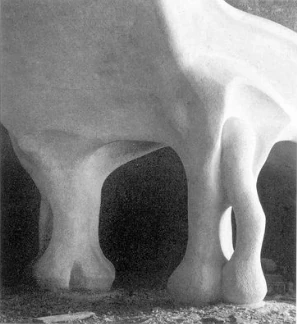

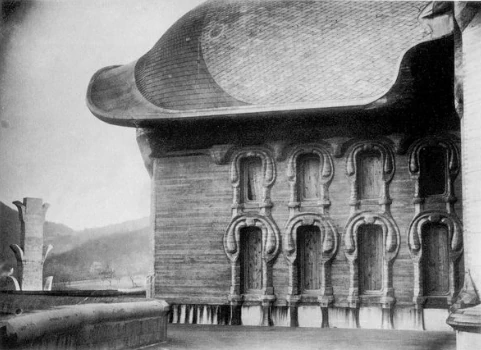

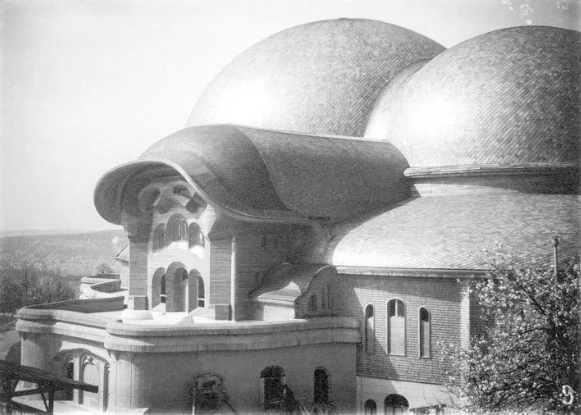

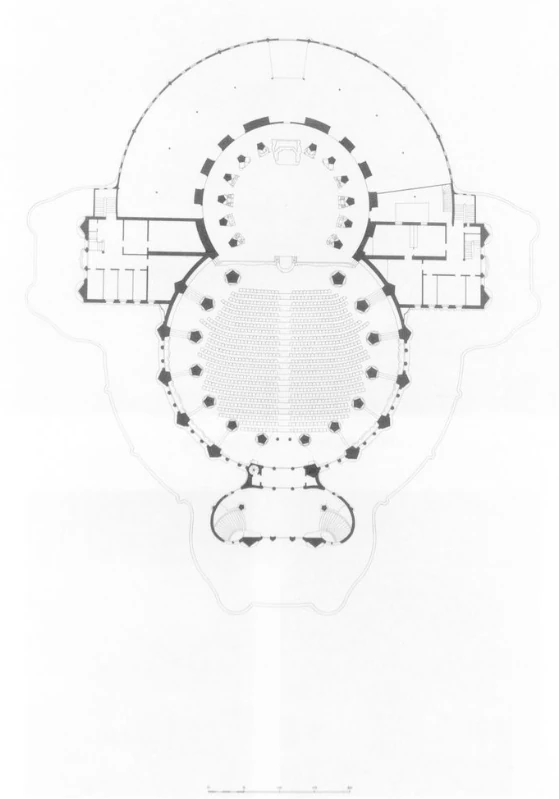

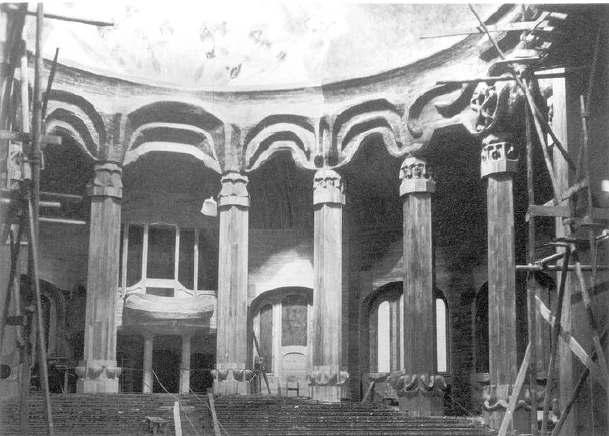

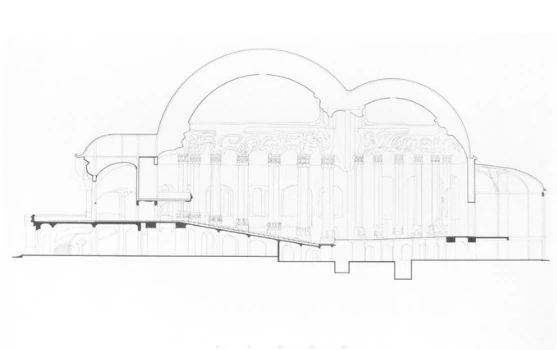

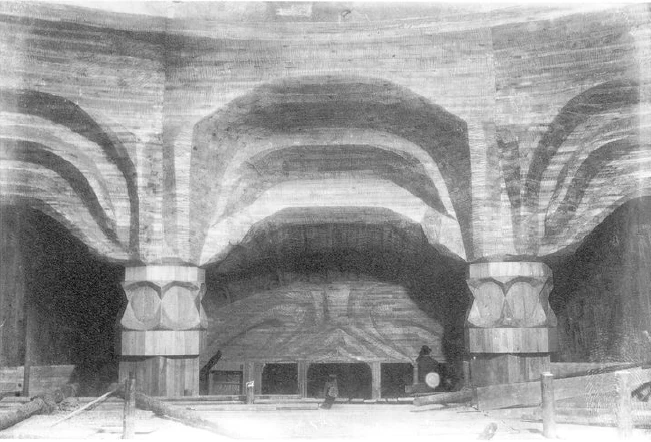

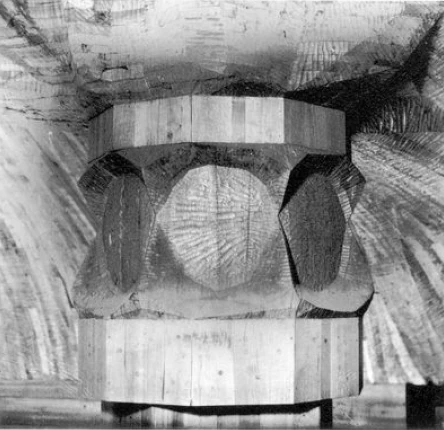

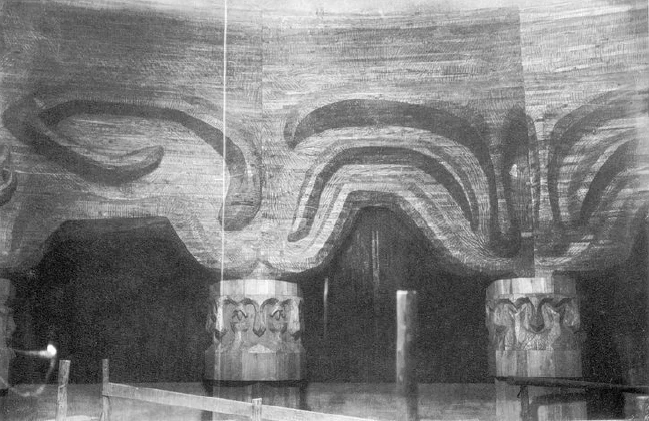

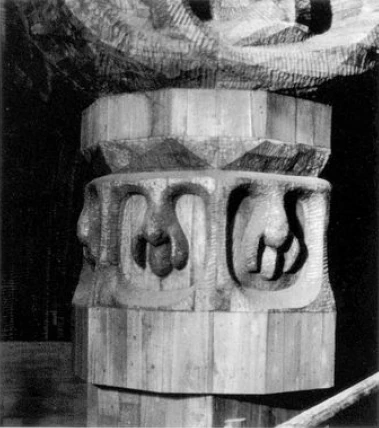

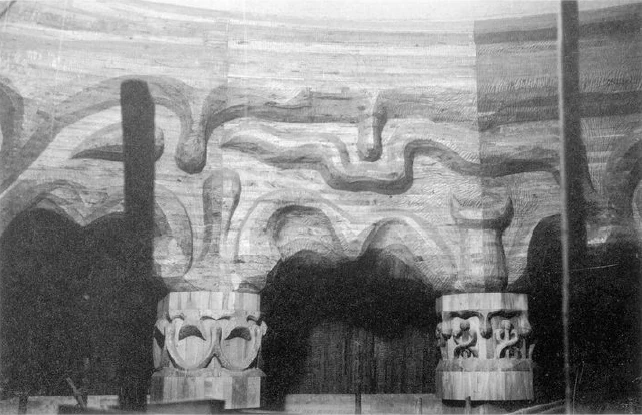

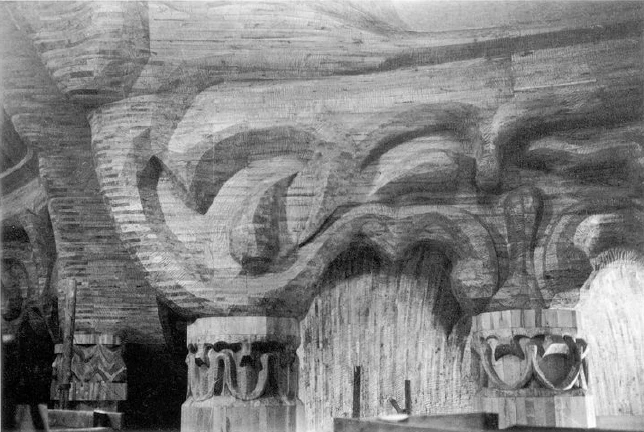

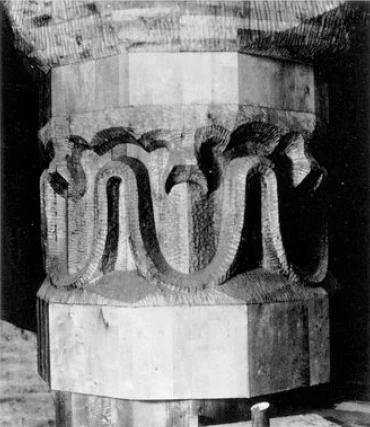

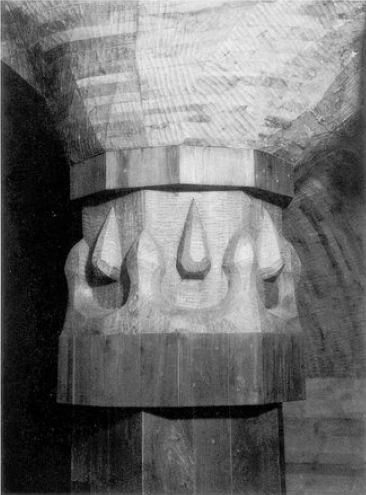

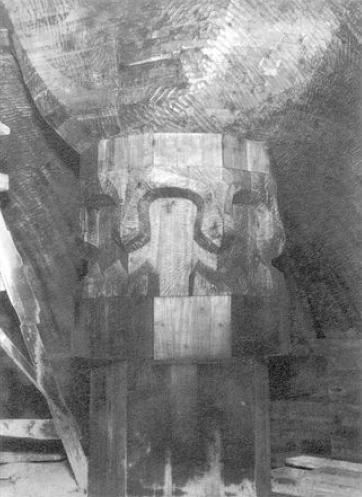

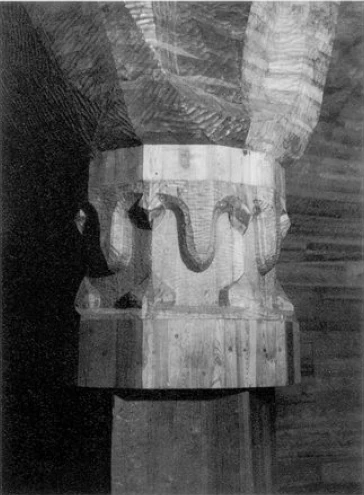

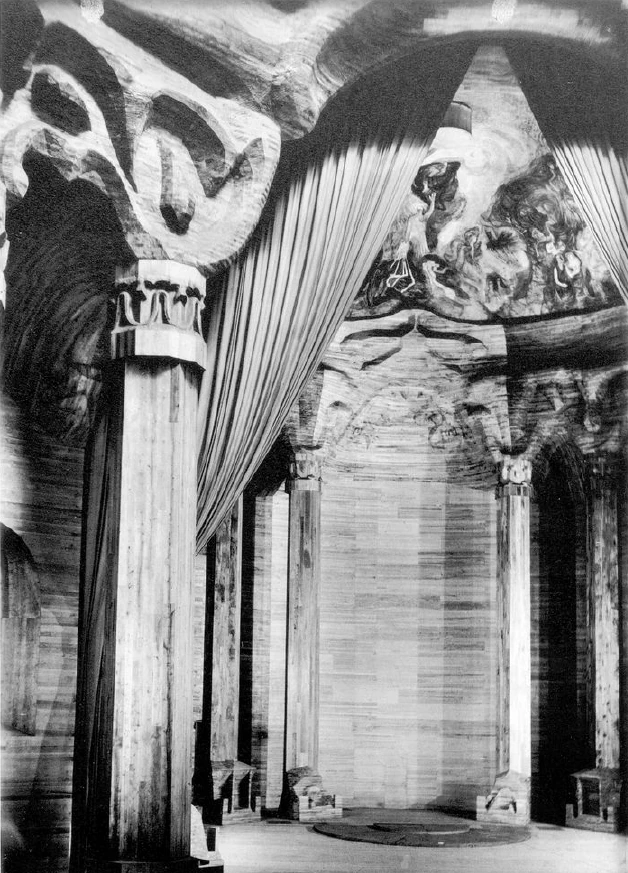

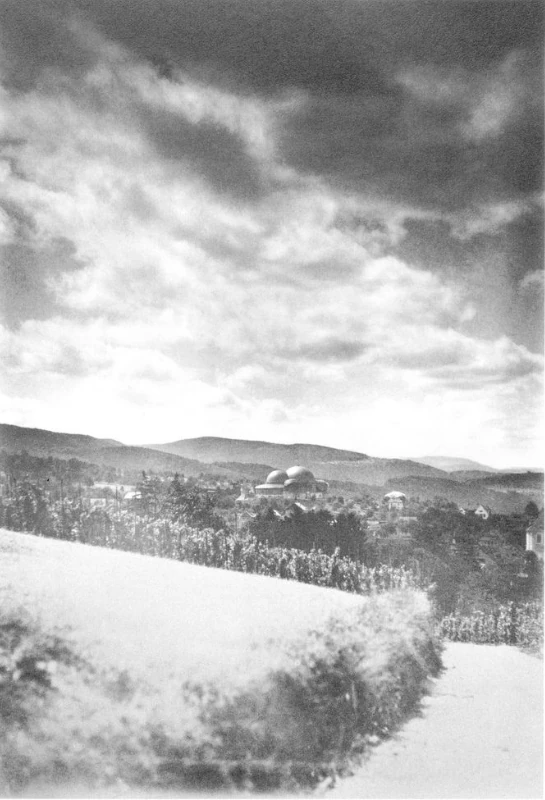

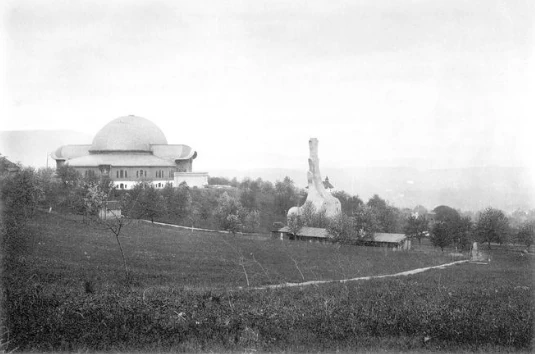

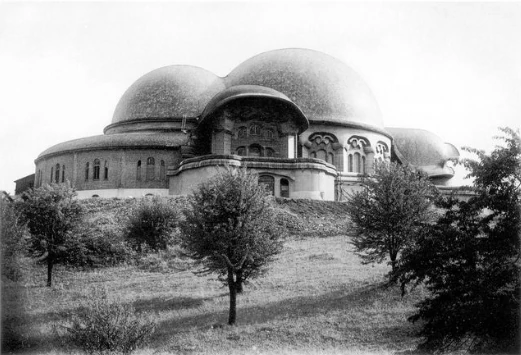

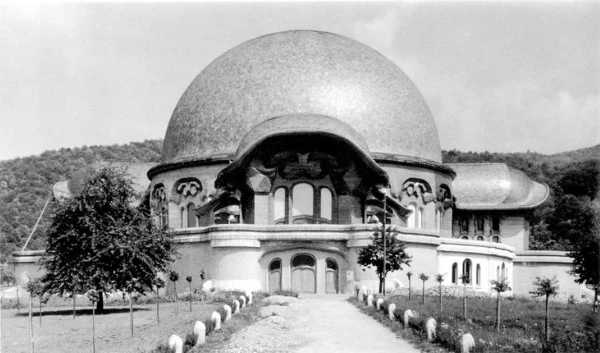

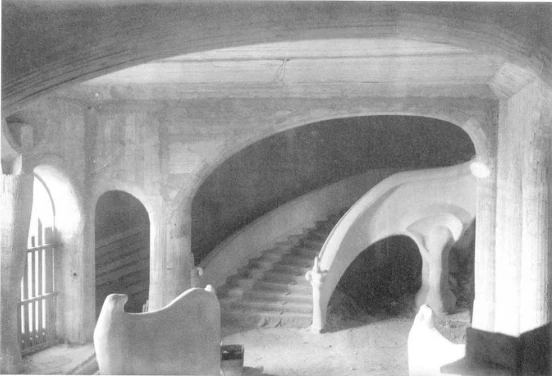

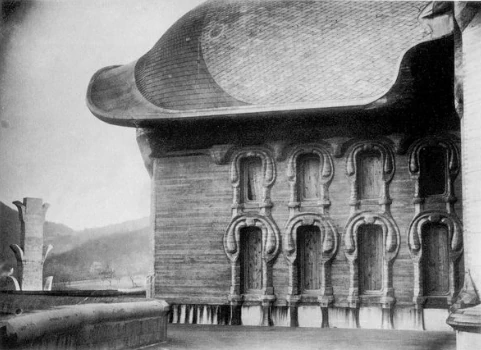

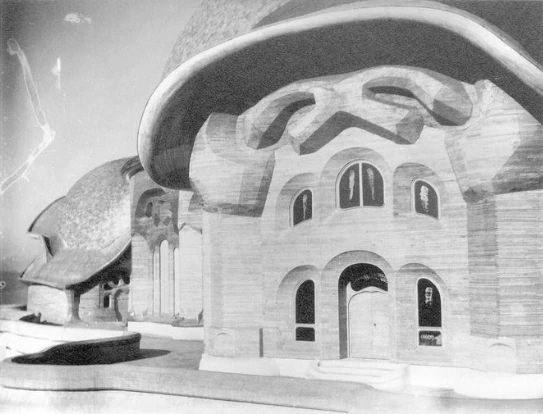

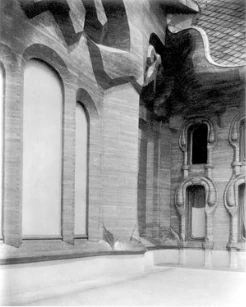

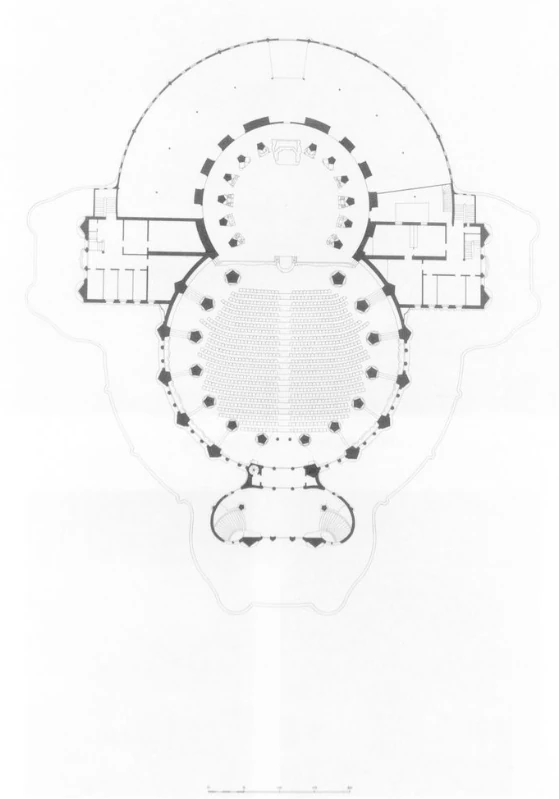

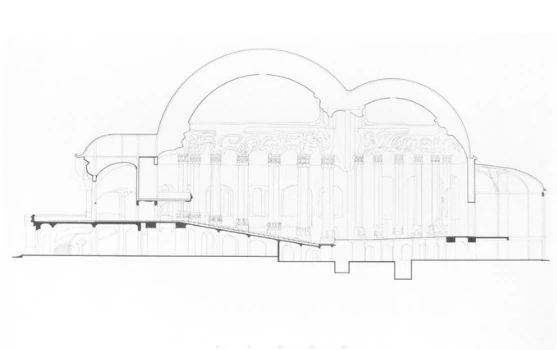

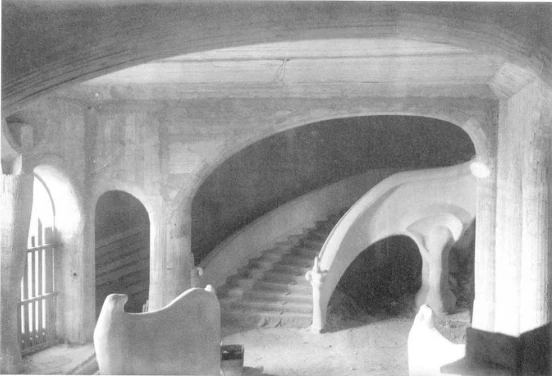

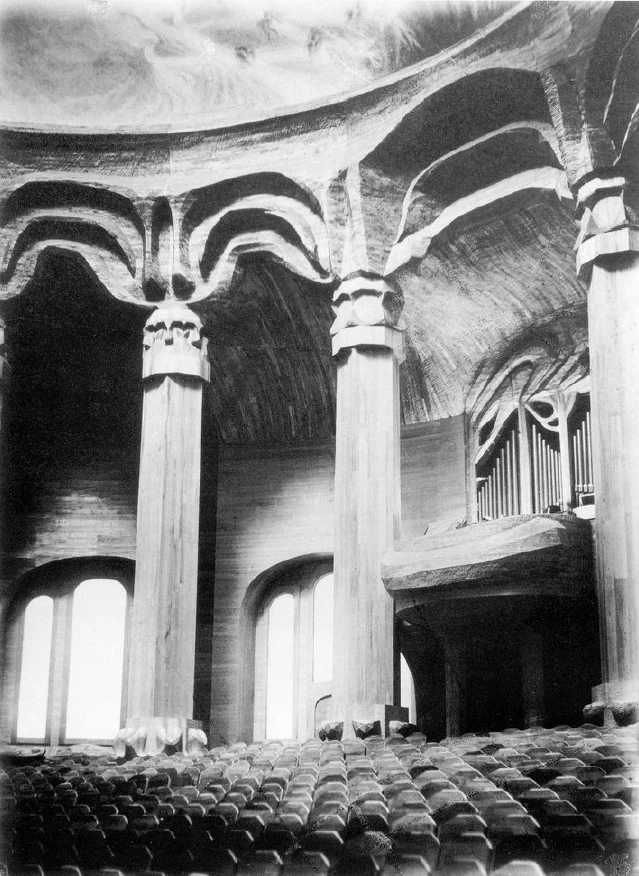

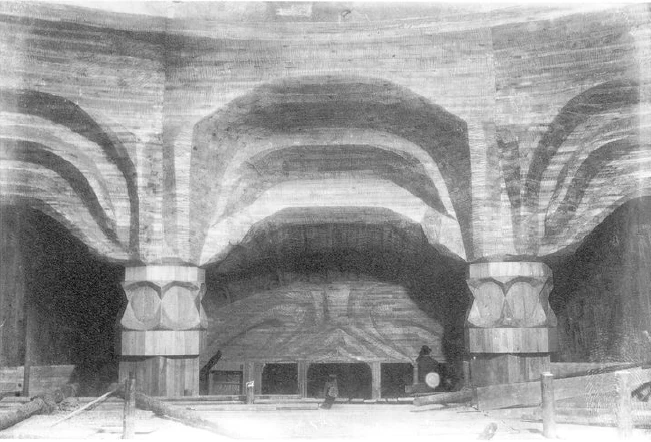

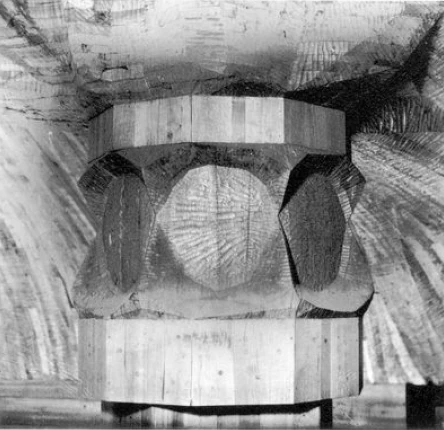

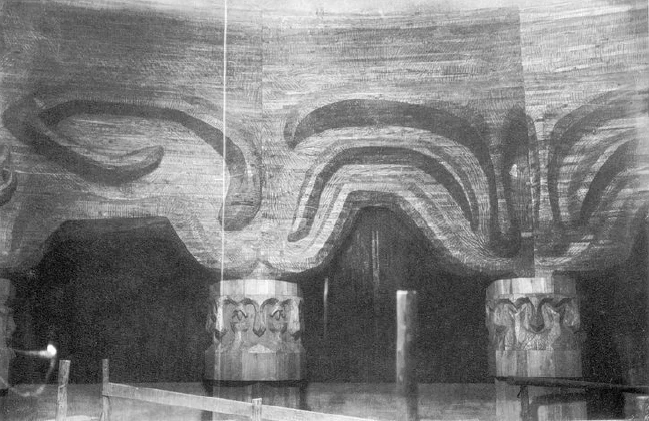

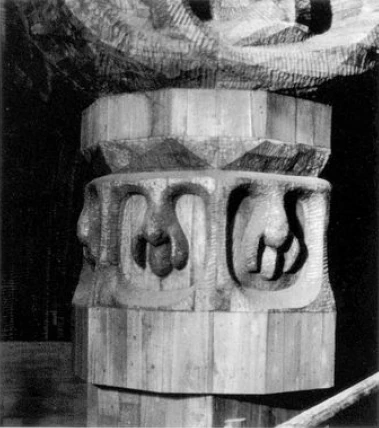

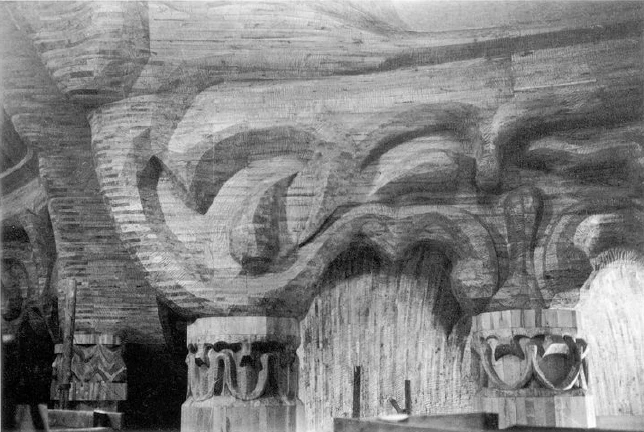

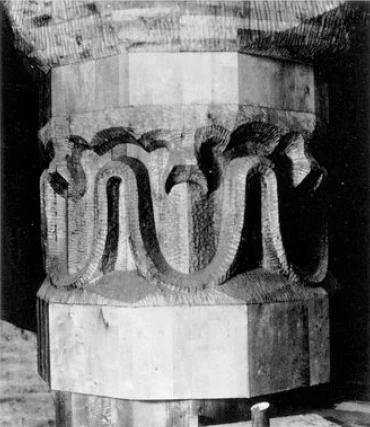

I would like to talk again today about the nature and significance of our building, for the reason that a number of external personalities are among us at the course for medical professionals. First of all, I would like to note that this building, as a representative of our anthroposophically oriented spiritual science, is intended to be in the world that which really gives an outward image of the significance and inner essence of this movement. If one wants to recognize this movement in its true significance, one must surely become familiar with the fact that this movement wants to enter the most diverse areas of life as something completely new, that its appreciation must arise from the realization that such a new thing is necessary in the face of the fact that old impulses in our present time clearly show how they are moving straight into decadence. If our movement had not emerged from that which the signs of the times themselves demand, from that which is not now in any human program, but from that which can be read in the spiritual development of humanity that lies behind our physical human movement, even if our movement were like so many other movements that also found societies, set up programs, and set up so-called ideals, then at a certain point this movement would have needed a larger building, larger premises for its membership, and they would have turned to some outside builder to have a house built. The architect would have built something in the traditional style, and the Society would have carried on its work in such a building. This is not how it should be with us. Rather, since we came to the point of being able to start a building project – which might even be completed one day – it had to be shown, precisely on the basis of this fact, how this spiritual movement, on the one hand, reaches the highest heights of spiritual life and, on the other hand, is a thoroughly practical movement that can directly engage with all aspects of practical life. That means that it had to be shown that our anthroposophically oriented spiritual movement is capable of producing new building forms, a new architectural style, out of itself. It had to be shown that our movement, down to the last detail, is not just a theoretical world-view movement, but something that can have a formative effect on everything that is placed externally in the physical world. Thus this building was not constructed as an outwardly unimportant house, but was built out of spiritual science, out of its very own feelings, ideas and thoughts, and in every detail it is an expression of what this spiritual science wants to be. It does not want to be some mystical driveling, it does not want to be some abstract theory, but it wants to be something that can deeply intervene in the most everyday life, and must therefore also intervene most in that which is to be its own representative. The whole of this structure should express how it places itself in the present as a living protest against what the centuries, the millennia, have brought to humanity and what is currently leading humanity to decline. Given that we could not build the structure in Munich due to the narrow-mindedness of the local artistic community, but had to erect it here on the Dornach hill, it must be seen as a stroke of good fortune that, by approaching the hill, this double-domed structure can now really be appreciated. For it is truly not for external reasons that this building has become a double-domed structure. This Goetheanum has become a double-domed structure – a building composed of a larger and a smaller dome – to show that something is to be revealed to contemporary culture and that something is to be received. That which emerges from the depths of spiritual life is represented by the small dome, and the fact of receiving is represented by the large dome. And I think that fate has done well that the one who approaches this hill in Dornach can already have the feeling, through the way in which this double dome rises above the hill, that something new is being added to human development, but something that can also have an effect on human development at the same time. The first pictures we will show you this evening should demonstrate to what extent this is the case. The first picture we will show is of the building as seen from the north.  Another aspect. Approached from a slightly different angle, the building looks like this.  The third picture is supposed to show the northeast aspect.  The fourth picture is intended to represent the southwest aspect.  The next picture is supposed to show the northwest aspect.  This is yet another aspect.  And now let us visualize how the building appears to someone entering from the west. The building is oriented from west to east. You enter at the bottom, and the cloakrooms are downstairs. You come up to the walkway through a stairwell and enter the building through the gates, which are in the west. The whole building is designed in such a way that it presents an organic architectural concept in contrast to the dynamic-mechanical architectural concept to which one is otherwise accustomed. Therefore, the forms everywhere are such that they blend in with the organism of the whole building, just as I would say that any limb – even the smallest in humans, the earlobe – blends in with the whole organism. Thus, a limb blends into the whole organism in such a way that it must be in its place, as it is, as large and as shaped as it is. In the same way, every detail should be in its place in this building; every detail should take its form from the overall form of the building. Furthermore, without falling back on mystical symbolism, there is not a single symbol in the whole building; everything in the building should be poured into artistic forms and show in artistic forms what task each individual piece has.  The West Gate. The West Gate has the task of welcoming those who enter. This welcoming, this receiving, this welcoming, so to speak, should be expressed in forms that are not geometric, but which should be expressively organic forms. As I said, you enter the building from below, via a staircase leading to the gallery, from where you then enter through the west gate.  Now the staircase. You are looking here towards the northern side of the staircase. It can be clearly seen from these things how everything here is designed so that it has to be in its place, where it is found. For example, you see how this column capital is perfectly adapted in form to this side, its inclination towards the place where the whole structure must be supported; narrowing on the other side, where the entrance is, where there is nothing more to support.  During on-site explanations, I have often pointed out this structure at the beginning of the staircase: there are three semicircular shapes with their planes perpendicular to each other. It is the shape that emerged in my mind when I tried to imagine how a person walking up these stairs would feel. He would have to feel at the point where the first step of the staircase begins: When I step into it, the external influences of life are calmed. Inner emotional movement will be found inside, which completely calms the outer feeling. In there I will stand on safe ground. That was what I wanted to express. This presented itself to me because I had to develop this thing here. It is a formation that has an external similarity to the three semi-circular canals in the ear, which, when injured, lead to dizzy spells that thus take away the certainty of the person when they are injured. But that is a discovery that occurred to me only afterwards; the matter itself is formed entirely out of the sensation.  You can also see a radiator cover. These radiator covers are designed in such a way that they represent, on the one hand, growing out of the earth, that is, the forces that grow out of the earth in a supersensible way and permeate the sensible; they are counteracted by other forces coming from above. For those who can perceive this interplay of forces, elemental figures emerge, and these elemental figures are expressed in the forms of these radiator covers, which are otherwise built in their entirety according to Goethe's principle of metamorphosis. Each radiator is the organic metamorphosis of the other. Each was designed to fit exactly into the place in the house where it belongs. But at the same time, the principle of metamorphosis is carried out with the same fidelity as in the plant itself. Every single form, every line, every curve is shaped according to the spatial and functional requirements, and I would say, the original form, which of course is not found here. Every curve is appropriate to the position of the limb of the structure on which the curve is located. A curve that is diverted points to something else in the structure, as opposed to a curve that is bent inward, as you can see here, where the perspective is not even quite right.  There we saw the same thing again, in more detail. You can see here how an attempt has been made to replace the conventional mathematical-dynamic pillar with something organic, which in its form has the character of support, of support through a force that comes from the elementary forces of the earth and is precisely suited to the distribution of the load that is to be supported at this point in the way in which it shapes its forms. Of course, I am well aware of the many objections that can be raised against such designs from the point of view of traditional architecture. But it is high time that an attempt was made to replace the usual dynamic-mechanical building concepts with an organic building concept that is based not on dynamics and mechanics but on organic principles.  Here we have again seen the side on one side of the main entrance, where you can see how they tried to bring out the character of this being a side piece, how it turns towards the center, how it points to the side. This shaping is particularly important.   The next picture. Here you can see the side wing, as it goes north, with its windows. And you can see here how it has been tried to overcome the merely decorative. Here, the support is led down everywhere, so that the windows stand up at the bottom, so that not only the windows are worked out of the wall like a decoration, but that the windows stand up everywhere. But you can also see how, in the room containing the motif in question, the same motif that is above the side windows above the main entrance reappears here at these windows. But if you can properly visualize the metamorphosis internally, then such motifs take on such a form that, from a purely external point of view, they no longer resemble other motifs at all, and yet they are actually the same. Just as the sepals and stamens are no different from the petals and leaves of a flower – even though the leaves take on completely different forms depending on the plant's position – so it is here. Thus, Goethe's idea of metamorphosis has been realized in its entirety in the artistic process.  Here we have the upper part of the side entrance. You see, once again, the same motif above, transformed, but also the motifs that you see everywhere, metamorphosed.   Here you see my original model, cut in half, that is, at the point where the axis of symmetry lies. The forms were first worked into this model. This model was, after all, the basis for the construction.  This is the floor plan of the building. This floor plan shows the extent to which the building is designed as a double-domed structure. The small domed room faces east. The main group will stand here, which all of you already know. Here is the west domed room, the auditorium. You can see that when you come in through the entrance, you enter the auditorium. You first come to a vestibule lined with wood, each individual piece of which is handcrafted, and all surfaces and curves are worked so that their surfaces and curves must be exactly where they are.  You enter below the organ (Fig. 29). The casing and framing are designed so that you can see that the organ is not just placed in the room, but grows organically out of the entire surroundings of the building. Then you always have a walkway on which you can walk around outside and below during intermissions. The auditorium holds about nine hundred or a thousand people. Then the entire perspective of the building is arranged according to an axis of symmetry; you won't find the same axis of symmetry anywhere else, everything is oriented towards this one axis of symmetry, while otherwise the auditorium is arranged, stepping forward, from seven columns on each side. These columns in the auditorium have bases, have capitals, and above them are architraves. Everything that is worked into these columns is done so in strict accordance with the principle of the evolution of nature itself. If you follow how the capitals, bases and architraves of the individual columns grow out of one another, you will see an image of evolution, of development, in the emergence of one motif from another. It is necessary to immerse oneself in the way in which one form grows out of another in these columns, with artistic devotion, with artistic sensitivity, just as one form of nature's development always grows out of another. It is not good to start from an abstract terminology in a philistine, pedantic way. There are certain reasons why one can name the one column Saturn's column, the other Venus' column, etc. But one must not obscure what is essential in the essence: the belonging together of the seven columns, the emergence of one column from the other. And above all, we must not obscure what lies in the forms themselves, which must be felt by following the line of swing, the curve of the form, by dreaming ourselves into a symbolism that does not exist. This is more inherent in the emergence of the form of one column from the form of the other column than in simply looking at a column. In the process, it turned out, by recreating nature itself, so to speak, that the idea of development, which is very often understood as if in each development the following stage of development is always more complicated than the one before, that this idea of development is not correct. Every development proceeds in such a way that at first there is a simple form; then a more complicated one develops from it, then an even more complicated one. This reaches a certain culmination; then again the forms begin to become simpler and simpler, and outwardly the most perfect form reveals itself as the one that has been simplified again. It is only an apparent simplification, but it is still a simplification, I would say, in the limbs, and there is a certain complication in the formation of the limbs. This is strictly adhered to here. You can see how the design of the columns becomes more complex up to the middle column, and then becomes simpler again towards the east, so that the seventh column is relatively simply designed again. The small domed room is closed off in this way on each side by six columns, the bases of which are designed to hold twelve seats, and here too the principle of development is fully adhered to for the capitals, the bases, the seats and the architraves. When you endeavor to recreate nature, it is the case that you only truly discover your findings in the finished product that you have created. One can – and this is something that only presented itself to me after the design of the matter in the model – one can, if one takes the raised, convex form of the first column, one can place it in the concave form of the seventh column in a truly artistic way, of course with metamorphosis, but with a true one. The second column fits with its raised part into the concave parts of the sixth column, the third into those of the fifth, and the fourth column stands alone as the central column. Of course, the same principle cannot occur in the same way in the six columns. There, the first and the sixth, the second and the fifth, the third and the fourth really correspond to each other as I have just expressed it. It is something that is found throughout nature, that certain polarities occur, and it was interesting that only the idea of development was retained in the formation of the forms, and that the polarities resulted automatically from the pure retention of the developmental idea.  The next picture: Here you have a section through the building in a west-east plane, so that the order of the columns is presented to you exactly as it can be shown in a section.  Here you can see the glass studio in the area below where the windows were cut, which I will talk about later. This glass studio is in some ways a kind of metamorphosis of the whole Goetheanum; only the metamorphosis is brought about by the fact that, firstly, the domes have been pulled apart and a central element has been added, and secondly, the domes have become the same size. For all such inner processes of drawing apart and becoming equally large, metamorphic experiences then arise for the whole organism of a thing. These are then faithfully executed in every detail. You can also see that the usual geometries in our building have been overcome by the fact that the symmetrical axis has been interrupted to the right and to the left. The idea that each individual piece should be seen in the context of the symmetry of the whole has been applied to the stairs. You will also see this when you look at the gate for this studio (Fig. 99), with the staircase, the shape of which has been designed in such a way that it really does represent a staircase, precisely because of its shape: you go in, you have a right and a left, while very many stairs that are designed are now really nothing closed, have no right and no left. All these things are to be considered when it comes to a truly artistic creation. The gate itself is designed in such a way that one recognizes its symmetry as a necessity. When you enter this glass studio, you will also see the lock. It is designed to differ from the usual philistine locks that are otherwise in use and which are really the opposite of anything beautiful.  The next picture: Now you see what has been most contested in a certain way, but which will also be understood over time. It is the building in which the heating and lighting are housed, the boiler house. And it is built according to the principle that what is inside has its envelope in the building. Just as a nutshell is shaped so that it is a shell for a nut, here the shell is entirely appropriate for what is inside, right up to the shapes of the chimney, which is only complete when it is smoking, because the smoke is part of these shapes; it then forms the top of the chimney. So everything is conceived according to the same principle by which nature creates when it forms the nutshell around the nut.  We will now turn our attention to the internal motifs. You have used the organ motif here as a model. The architecture around the organ should be such that the whole structure is organically integrated into it, so that one does not have the feeling that the organ has been placed in some random location, but rather that the organ grows out of the whole organization, as it were.  So, by walking through the space below the model and then turning around, we have the two symmetrical columns in the auditorium with the simplest architrave motif at the top. We will now look at each individual column each time.  And as we advance, we first see here the simplest column, one of the two, and now, after we have let its forms act on our perception, we will look at it in connection with the second column.  We shall see how what is simple here [at the first column] grows downwards, how the lower part grows towards it, and how what grows downwards, what grows from top to bottom, undergoes a certain complication of forms, from top to bottom undergoes a certain complication of forms, thereby pushing forward other rising motifs. This can only be felt by observing the succession of the two columns. It is precisely this succession that must be observed. You can also see here how the architrave motif becomes more complicated. It is actually the case that by immersing yourself in these forms, you can learn more about the idea of development, the developmental principle, the developmental impulse in nature than through any theoretical discussion. Because nature is such that it creates in images, and it must be emphasized again and again that, even if our philosophers prove that one should work with abstractions, with analyses and with the discursive principle to build a science of nature, then nature simply turns its nose up at this science and does not let itself be grasped in this way; it eludes comprehension and leaves us alone with our abstractions. Because it does not create in natural laws, it creates in images. But now, when we can rise to imaginations in abstract terms, we enter into nature and understand nature's growth. The entire structure should be designed in such a way that it is simultaneously the great hieroglyph through which the world can be grasped. Wherever you look in this structure, you should have a starting point for understanding the world. That is what is, if I may use the term, secretly woven into this structure, that in looking at these forms, that which, so to speak, governs the world at its core, is presented.  We will now see the second pillar on its own.  And now again the second with the third column in relation, with the modified architrave motifs. You see how here again the forms become more complicated from top to bottom, and how they are met by forms that become more compact towards the bottom. However, these forms can only be produced, one from the other, if the artistic design is based on the same developmental forces that nature uses to form a plant leaf by leaf, or in a series of developing creatures, one species emerges from the other, one species develops out of the other. By imitating nature, such forms are created. And those who immerse themselves in nature will succeed in recognizing the principle of development in nature. Indeed, something has been set up in this building that should inspire people to say: what surrounds me here as something growing, what surrounds me here as something formed, is something that stands as an explanation of the whole surrounding world.  We will now see the third column on its own.  And now we will see the third column in relation to the fourth column again. You can also see that the architrave motifs are becoming more complicated. You just have to imagine how, according to the principle of growth, one emerges from the other, one grows over the other, and you do not need to say: here is a caduceus, but you have a principle of growth that emerges out of it, grows over it, breaks through the overgrowth, and the caduceus does not stand there as an isolated symbol, but as a developmental phenomenon, as a developmental form that emerges from the other. It is the same below with the capital motif.  We will now look at the fourth column on its own.  Now again this column with the following one. You can see how purely by one growing over the other, this caduceus, snake-staff-like structure emerges. It is taken entirely from the growth, not placed as an isolated motif. It is perhaps also cleverer in the usual intellectual sense to throw one motif after the other. That is not what is aimed for here. The aim here is for each motif to emerge from the last, and for the harmony of the motifs to give the actual impression of reality.  The fifth column on its own.  Now again this column with the next. You can see how here, through the continued growth, not a complication occurs, but a simplification. The architrave motifs have long since become simpler; but here you can see how this motif simply continues to grow, grows upwards, and the motif arises in a completely natural way. In growing, there is always a pushing away. The two parts below here grow upwards; this is rejected, and the motif emerges in a natural way. This is eliminated as it grows; on the other hand, this grows downwards and the shape emerges quite organically from what went before.  The sixth motif on its own.  And again this motif together with the next one. You can see how the next motif simply emerges from the previous one by growing further, growing, then overgrowing at the top and finally merging.  Now the seventh motif on its own. Another simplification, but a complication in the lines. Tomorrow I will show you this artistic element, which lies in the complication and simplification, by means of a simple representation on the board. We have now arrived at the point where the curtain column is, where the large dome space merges into the small one. Here you have the last column, the connection between the large and small dome spaces.  We are now moving further into the small domed room. You can see that it goes into the small domed room.  We have here the order of the columns and the architraves of the small domed room. If you remember how the two motifs were on the other columns, you will see that the forms have been changed to reflect the fact that this is a smaller room with only six columns. You just need to consider the following: If you have seven columns that are supposed to create a unified effect, then you have to give each column a different shape. Then imagine circling the same space with six columns instead of seven. In that case, the distances between the columns, which are one and one-seventh, or 8/7, would be different in relation to the previous ones, and so individual shapes would now be changed. And here, in addition, you have the smaller dome space. This further changed the forms. You see, when something like this is created, you get what I would call a sense of space. Those who think abstractly – and such thoughts have even appeared in scientific literature – are of the opinion that, for example, one can also imagine a human being as very small, atomistically small, that size itself, the spatial volume, has no relationship to the being. But this is not true. Anyone who has immersed themselves in the essence of artistic creation knows that a particular form can only be reproduced in a particular spatial volume, that the size of the space is in an inner relationship to what is being depicted. If you have conceived of some figure for a particular large space, and you then make it en miniature, it seems distressing. But this feeling must be there. The artistic elements must be coordinated with their spatial content to this extent, otherwise they are not truly artistically designed.  The next picture shows another row of columns from the smaller dome with the corresponding architrave. You can see the slit for the curtain, the first column, the second column and so on. We will study the individual columns in their sequence later.  The first column of the small dome.  The next one will now be more complicated, according to the growth principle.  The next one is more complicated again.  Now it is about simplification, but it is a sham simplification; it is simply an outgrowth.  The next column.  There we come to the two columns that border the east end.  We have the carvings of the east end here. You will see them if you look closely. I would say that the forms here can be felt more than seen. If you look closely, you will find that the carving here in the east end encompasses everything that the other forms of the columns and the architraves contain, but of course modified for the vaulting of the room, metamorphosed. Above it a five-petal flower. Anyone who wants to can imagine a pentagram there, but in the same way that one can imagine one in a five-petal plant leaf in nature. A symbolist would have put any old pentagram there. But then one would be acting according to the principle by which we have often acted. Time and again, we have had to experience that artists came to our branch offices who were unpleasantly touched by the fact that unartistic motifs were found everywhere. A cross that was ugly in design, with seven roses around it, was something that was considered more dignified than something truly alive in artistic forms. It is precisely when one is able to pour the spiritual out completely into artistic forms that what is to be achieved here is achieved: not intrusive symbols, but a shaping in forms in which the spirit lives. When we describe how the Earth developed from Saturn, the Sun and the Moon [gap in the text], we do so in such a way that what lives in the whole also lives in the ideas of our worldview. However, it does not live by expressing itself symbolically through any form, but rather the forms themselves have real inner forces of growth.  Here you can see this eastern end a little more clearly in its individual forms.  The next picture is a detail of the side of the small domed room. And now, my dear friends, I have begun to use these pictures to explain something about the building to you. I will continue this discussion tomorrow so that those who are hearing it for the first time will get a complete picture of what our building should be from this presentation. I will continue these reflections tomorrow with the help of more slides. |

| 288. Architecture, Sculpture and Painting of the First Goetheanum: The Symbolism of the Building at Dornach II

05 Apr 1920, Dornach Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| 288. Architecture, Sculpture and Painting of the First Goetheanum: The Symbolism of the Building at Dornach II

05 Apr 1920, Dornach Rudolf Steiner |

|---|